1 Health Systems Around the World

Health Systems Around the World

In this first topic, we will consider how the U.S. health system compares to the health systems of other developed, wealthy countries around the world. Specifically, you will be asked to read short overviews of the healthy systems in the United States and six other developed countries. Each of these profiles provides a short overview and some key data allowing you to compare the overall structure, challenges, and outcomes of each health system. You will then be asked to watch an hour-long PBS News Hour documentary, highlighting the experiences of individual patients in the United States and other developed countries.

Commonwealth Fund – International Health Care System Profiles

Please begin by reading the 2020 “Health System Overview” for the seven countries linked below. These overviews were developed by the Commonwealth Fund. For your convenience, we’ve copied the text and graphics of each overview directly into this textbook. Alternatively, you can read each overview in a 2-page PDF using the links below. Please access the content through the means most convenient for you.

- United States (alternative link: 2020_IntlOverview_USA)

- Australia (alternative link: 2020_IntlOverview_AUS)

- Canada (alternative link: 2020_IntlOverview_CAN)

- Switzerland (alternative link: 2020_IntlOverview_SWITZ)

- England (alternative link: 2020_IntlOverview_ENG)

- Germany (alternative link: 2020_IntlOverview_GER)

- Japan (alternative link: 2020_IntlOverview_JAPAN)

The Commonwealth Fund developed profiles of the health systems of 20 different countries. If there are other countries of interest to you, we would encourage you to explore the other Country Profiles as well.

****

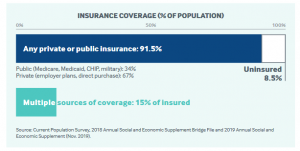

The U.S. health system is a mix of public and private, for-profit and nonprofit insurers and health care providers. The federal government provides funding for the national Medicare program for adults 65 and older and some people with disabilities, as well as for various programs for veterans and low-income people, including Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program. States manage and pay for aspects of local coverage and the safety net. Private insurance, the dominant form of coverage, is usually provided by . The uninsured rate of 8.5 percent is down from 16 percent in 2010, when the landmark Affordable Care Act (ACA) was enacted. Insurers set their own benefit baskets and cost-sharing structures, within federal and state regulations.

H E A LT H SYSTEM OVERVIEW DEMOGRAPHICS

16.0% Population age 65+

CAPACITY & UTILIZATION

2.6 Practicing physicians per 1,000 population

4.0 Average physician visits per person

11.7 Nurses per 1,000 population

2.8 Hospital beds per 1,000 population

125 Hospital discharges per 1,000 population

$10,586 Health care spending per capita

$1,122 Out-of-pocket health spending per capita

$1,220 Spending on pharmaceuticals (prescription and OTC) per capita

78.6 Life expectancy at birth (years)

40.0% Obesity prevalence

10.8% Diabetes prevalence

28% Adults with multiple chronic conditions (2 or more)

HEALTH CARE DELIVERY AND PAYMENT

Primary care practitioners work mostly in private practice. Primary care physicians are paid through a combination of methods, including negotiated fees (private insurance), capitation (private insurance and some public insurance), and administratively set fees (public insurance). The majority (66%) of primary care practice revenues come from fee-for-service payments. Practitioners generally have no gatekeeping function; patients have free choice of physician. Patient cost-sharing: Most patients face cost-sharing, varying by insurance type. Some plans cover primary care visits before the deductible is met and require only a copayment.

Specialists work in outpatient private practice or hospitals; some work in both. Single-specialty practices predominate. Specialist practices are increasingly integrating with hospital systems and consolidating with each other. Outpatient specialists can choose which form of insurance they will accept; for example, not all specialists accept publicly insured patients, because of the relatively lower reimbursement rates set by Medicaid and Medicare. Access to specialists for beneficiaries of these programs can therefore be particularly limited. Patient cost-sharing: Varies by type of insurance. Most private insurance includes deductibles, with lower cost-sharing for use of in-network providers.

Hospitals are mostly nonprofit (56%), with the remainder public or for-profit. Main forms of payment are: prospective diagnosis-related group (DRG) rates for Medicare; DRG, per-diem, or cost reimbursement for Medicaid; and negotiated per-diem fees for private insurance. Cost- sharing: Medicare charges full cost up to $1,364 deductible for days 0–60; thereafter, $0 per day. Cost-sharing applies for stays over 60 days. Copayment required by most private plans. Medicaid charges $75 maximum per stay for most patients.

TOTAL HEALTH EXPENDITURES

Annual per capita health expenditures are the highest in the world — USD $11,172, on average, in 2018. In 2017, public spending accounted for 45 percent of total health care spending, or approximately 8 percent of GDP.

RECENT REFORMS

• Two bills passed in 2018 banned so-called gag clauses in contracts between pharmacies and pharmacy benefit managers that have prevented pharmacists from informing customers when the cash price (without insurance) for a drug is lower than the negotiated price. In addition, new federal rules require all hospitals to post their charges for medical procedures online and update the list at least once a year

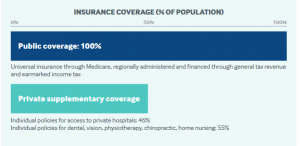

December 2020Australia has a regionally administered, universal public health insurance program (Medicare) that is financed through general tax revenue and a government levy. Enrollment is automatic for citizens. New Zealand citizens, permanent residents, and people from countries with reciprocal benefits are eligible to enroll in Medicare, which includes free hospital care and substantial coverage for physician services, pharmaceuticals, and certain other services. Approximately half of Australians buy private supplementary insurance to pay for private hospital care, dental services, and other services. The federal government pays a rebate toward this premium and also charges a tax penalty on higher-income households that do not take up private insurance.

H E A LT H SYSTEM OVERVIEW DEMOGRAPHICS

15.6% Population age 65+

CAPACITY & UTILIZATION

3.7 Practicing physicians per 1,000 population

7.7 Average physician visits per person

11.7 Nurses per 1,000 population

3.8 Hospital beds per 1,000 population

181 Hospital discharges per 1,000 population

$5,005 Health care spending per capita

$837 Out-of-pocket health spending per capita

$673 Spending on pharmaceuticals (prescription and OTC) per capita

82.6 Life expectancy at birth (years)

30.4% Obesity prevalence

5.1% Diabetes prevalence

15% Adults with multiple chronic conditions (2 or more)

HEALTH CARE DELIVERY AND PAYMENT

General practitioners (GPs) are typically self-employed, with about four physicians per practice on average. No patient registration required. Paid mostly on fee-for-service basis, with some pay-for-performance incentives. Patient cost-sharing: Mostly none; 14 percent of GPs charge fees averaging $22. Specialists deliver outpatient care in private practice or in public hospitals. Patients can choose specialists but must have GP referral to receive government subsidies. Paid mostly on fee-for-service basis. Patient cost-sharing: $56 on average.

Hospitals are mostly public (65% of beds). Public hospitals are organized into Local Hospital Networks and paid mainly through activity-based payments (DRGs). Private for-profit and nonprofit hospitals are paid fee-for-service. Patient cost-sharing: None at public hospitals for publicly insured patients; private voluntary insurance subsidizes some private hospital fees. All costs are in U.S. dollars, adjusted for cost-of-living differences.

Conversion rate: AUD 1.00 = USD 0.72

Prescription drugs i outpatient settings are covered under the Medicare Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS). Patient cost-sharing: Generally none for drugs received in hospitals. Maximum copay of $28 per prescription (plus potential additional fees); reduced to $4.20 after patient spends $1,064 in calendar year. Low-income adults pay $4 per prescription, with no cost- sharing once reaching $268 cap for calendar year.

Mental health services are provided by GPs and specialists, community-based care, hospitals (in- and outpatient), and residential care. GPs, specialist care, and pharmaceuticals are subsidized through Medicare and PBS.

Long-term care in nursing homes is provided by private and public facilities, some of which are federally subsidized residential facilities that require a needs assessment. Permanent residential care is means-tested. Most elderly persons with long-term care needs receive informal care (75%); 60 percent receive formal assistance. Various government programs provide financial assistance to informal caregivers.

Safety nets include the Original Medicare Safety Net, covering Medicare schedule fees toward out-of- hospital services above an annual out-of-pocket threshold ($332). The Extended Medicare Safety Net covers 80 percent of out-of-pocket, out-of-hospital costs over an annual threshold for low-income adults, seniors, and caregivers. The “Greatest Permissible Gap” sets a maximum out-of- pocket fee per out-of- hospital service ($57).

Care coordination is incentivized through the Practice Incentives Program (PiP) and Primary Health Networks (PHNs), funded through government grants and other programs.

TOTAL HEALTH EXPENDITURES

Nationally, total health spending represented 10.3 percent of GDP in 2015–2016. Public spending accounted for 67 percent of the total.

RECENT REFORMS

• Reforms to the aged care system address financial sustainability, quality of care, consumer choice, and social isolation (2018).

• Additional government funding for strengthening suicide prevention and mental health care, as well as health care for children and youth.

This overview was prepared by Lucinda Glover, with contributions from Michael Woods.[2]

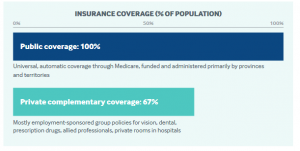

Canada has a decentralized, universal, publicly funded health system called Canadian Medicare. Health care is funded and administered primarily by the country’s 13 provinces and territories: each has its own insurance plan, and each receives cash assistance from the federal government on a per-capita basis. Benefits and delivery approaches vary as well. All citizens and permanent residents, however, receive medically necessary hospital and physician services free at the point of use. To pay for excluded services, including outpatient prescription drugs and dental care, provinces and territories provide some coverage for targeted groups. In addition, about two-thirds of Canadians have private insurance.

H E A LT H SYSTEM OVERVIEW DEMOGRAPHICS

17.3% Population age 65+

CAPACITY & UTILIZATION

2.7 Practicing physicians per 1,000 population

6.8 Average physician visits per person

10.0 Nurses per 1,000 population

2.5 Hospital beds per 1,000 population

SPENDING

$4,974 Health care spending per capita

$749 Out-of-pocket health spending per capita

$806 Spending on pharmaceuticals (prescription and OTC) per capita

82.0 Life expectancy at birth (years)

26.3% Obesity prevalence

7.4% Diabetes prevalence

22% Adults with multiple chronic conditions (2 or more)

HEALTH CARE DELIVERY AND PAYMENT

General practitioners (GPs) are typically self-employed and in private practice. Paid mostly on fee-for-service basis, with fees negotiated between provincial ministries of health and medical associations. Patient registration requirements vary, but no province or territory has strict rules. Patient cost-sharing: None for medically necessary services. Patient cost-sharing for services not covered by public plans.

Specialists deliver outpatient care primarily in hospitals, although less-complex services may be provided in private diagnostic or surgical facilities. Mostly self-employed and paid on fee-for-service basis, typically under the same fee schedule as GPs. Patients can freely choose specialists, but in many provinces specialists receive lower fees when patients are not referred by GPs. Patient cost-sharing: None for medically necessary services. Patient cost-sharing for services not insured by public plans.

Hospitals are a mix of public and private and predominantly not-for-profit. Often managed locally by regional authorities or hospital boards representing the community. Paid primarily through annual global budgets. Patient cost-sharing: None, except for private room fees. All costs are in U.S. dollars, adjusted for cost-of-living differences.

Conversion rate: USD 1.00 = CAD 1.26.

Prescription drugs provided in hospitals are paid under Canadian Medicare. Publicly funded outpatient drug coverage for individuals without private supplemental insurance through an employer varies by province and territory. Patient cost-sharing: For outpatient drugs, varies across provinces and territories depending on safety-net programs.

Mental health services provided by physicians are covered under Canadian Medicare, and the provinces and territories also provide a range of community mental health and addiction services. Patient cost-sharing: Visits to providers other than physicians (e.g., psychologists) are mostly paid out of pocket or with private insurance (or some combination of the two).

Long-term care provided outside hospitals is not insured by Canadian Medicare, but provinces and territories subsidize some home and institutional services. Long-term care facilities are a mix of private and public. Home care is publicly funded through contracts with home care agencies or via government stipends to patients who purchase their own services. In some provinces and territories, means-testing is required for long-term care. Support for informal caregivers varies by province and territory. Patient cost-sharing: Many provinces require a copayment for nursing home and home care services.

Safety nets include outpatient drug plans that provinces and territories provide to some resident subgroups (e.g., recipients of social assistance, individuals age 65 years and older, or those who lack private health insurance). Provincial/territorial governments also pay for certain accommodations and food expenses for indigent individuals in publicly financed long-term care facilities. The federal Medical Expense Tax Credit provides tax credits for individuals with significant out-of-pocket medical expenses.

Care coordination for chronically ill patients with complex needs is being encouraged by the provinces and territories through various initiatives, including a bundled payment pilot program in Ontario.

TOTAL HEALTH EXPENDITURES

Health spending accounted for an estimated 11.5 percent of GDP in 2017. Public funds paid for approximately 70 percent of expenses. The federal government contributed USD 29.4 billion to provinces and territories in 2017–2018 for health care, representing approximately 24 percent of provincial and territorial health expenditures.

RECENT REFORMS

• Provincial and territorial governments are implementing structural reforms to improve efficiency, with a recent trend toward centralizing the administration of health services into a single provincial health authority, including in Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Ontario (2016–2019

• The Advisory Council on the Implementation of National Pharmacare was established in 2018 to consider a pan-Canadian system of drug coverage.

This overview was prepared by Sara Allin, Greg Marchildon, and Allie Peckham.[3]

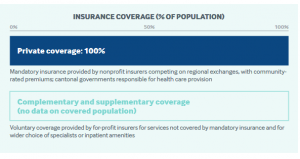

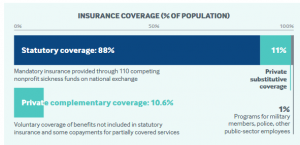

December 2020Switzerland’s universal health care system is highly decentralized, with the cantons, or states, playing a key role in its operation. The system is funded through enrollee premiums, taxes (mostly cantonal), social insurance contributions, and out-of-pocket payments. Residents are required to purchase insurance from private nonprofit insurers. Adults also pay a yearly deductible in addition to coinsurance, with an annual cap for all services. Coverage includes most physician visits, hospital care, pharmaceuticals, devices, home care, medical services in long-term care, and physiotherapy. Supplemental private insurance can be purchased for services not covered by mandatory health insurance to secure greater choice of physicians and to obtain better hospital accommodations.

H E A LT H SYSTEM OVERVIEW DEMOGRAPHICS

18.3% Population age 65+

CAPACITY & UTILIZATION

4.3 Practicing physicians per 1,000 population

4.3 Average physician visits per person

17.2 Nurses per 1,000 population

4.5 Hospital beds per 1,000 population

171 Hospital discharges per 1,000 population

$7,317 Health care spending per capita

$2,069 Out-of-pocket health spending per capita

$963 Spending on pharmaceuticals (prescription and OTC) per capita

83.6 Life expectancy at birth (years)

11.3% Obesity prevalence

5.6% Diabetes prevalence

15% Adults with multiple chronic conditions (2 or more)

HEALTH CARE DELIVERY AND PAYMENT

General practitioners (GPs) typically are self-employed. About half of all physicians are in solo practice. Most GPs are paid according to national fee-for-service scale, with some capitated payments from managed care plans. No patient registration required, except in some managed care plans. Billing above fee schedule not permitted. Patient cost-sharing: Full cost up to deductible, plus 10 percent coinsurance.

Specialists, most of whom are self-employed, typically work in urban areas near hospitals. Patients can choose their own specialist without referral unless they are enrolled in a gatekeeping plan. Specialists are paid according to the same national fee-for-service scale as GPs. Billing above the fee schedule is not allowed. Patient cost-sharing: Full cost up to deductible, plus 10 percent coinsurance.

Hospital inpatient services, public and private, are billed through a national diagnosis-related group payment system. Hospitals receive at least 55 percent of their funding from cantons, with the rest covered by mandatory health insurance (MHI) and patients. Hospital-based physicians are normally salaried. Patient cost-sharing: Full cost up to deductible, plus 10 percent coinsurance and USD 12 copay per day.

All costs are in U.S. dollars, adjusted for cost-of-living differences.

Conversion rate: USD 1.00 = CHF 1.21

Prescription drugs are covered following an evaluation of their effectiveness and cost. Pharmacists are largely reimbursed at flat rates, so they have fewer financial incentives to dispense more-expensive drugs. Patient cost-sharing: Full cost up to deductible, plus 20 percent coinsurance for brand-name drugs that can be substituted and 10 percent for generics.

Mental health services are covered by MHI if provided by certified physicians or by nonphysicians — such as psychotherapy provided by psychologists — when prescribed by a physician and provided at the physician’s practice. There are also socio-psychiatric facilities and day care institutions, run and funded mainly by the cantons, that treat patients with less-acute symptoms. Prices for outpatient psychiatric services follow the national fee-for-service scale, while inpatient care prices are set with a tariff system. Patient cost-sharing: Subject to same user fees as other health services.

Long-term care is provided through home care organizations and mostly private nursing homes. Some long-term care services, including home care, are covered under mandatory health insurance. Patient cost-sharing: Up to 20 percent of care-related costs in nursing homes and institutions, with remaining costs financed by canton or municipality. Individuals also pay portion of outpatient long-term care, financed mainly by MHI, voluntary health insurance, other social insurance, and government subsidies.

Safety nets take the form of income-based subsidies from the federal and canton governments to cover MHI premiums. In addition, municipalities or cantons cover health insurance expenses for social assistance beneficiaries and recipients of supplementary old age and disability benefits. Maternity care and some preventive services, such as cancer screenings, are exempt from cost-sharing. Children and young adults in school (up to age 25) are exempt from additional per-diem charge.

Care coordination has become a national priority, particularly for palliative care, dementia, and mental health.

TOTAL HEALTH EXPENDITURES

In 2016, total health expenditures represented 12.2 percent of GDP, among the highest in the world. Publicly financed health care accounts for 62.8 percent of health spending.

RECENT REFORMS

• The Swiss Federal Council’s national Health2020 strategy has four main objectives: maintain quality of life; increase equal opportunities; raise the quality of care; and improve transparency, governance, and coordination. Priorities are set for each year of implementation.

• A national cost-containment program was adopted in 2018. The first package of nine measures, adopted in 2019, features improved cost-control and tariff schemes and a reference pricing system for pharmaceuticals. In 2020, a second package of initiatives on improving cost transparency and care coordination is anticipated.

• A new electronic patient record system will be rolled out by 2020 to improve care

coordination, safety, quality, and efficiency.

This overview was prepared by Isabelle Sturny[4]

All English residents are automatically entitled to free public health care through the National Health Service (NHS), including hospital, physician, and mental health care. The NHS budget is funded primarily through general taxation. A government agency, NHS England, oversees and allocates funds to 195 Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs), which govern and pay for care delivery at the local level. Approximately 10.5 percent of the U.K. population carries voluntary supplemental insurance to gain more rapid access to elective care.

H E A LT H SYSTEM OVERVIEW DEMOGRAPHICS

18.2% Population age 65+

CAPACITY & UTILIZATION

2.8 Practicing physicians per 1,000 population

7.8 Nurses per 1,000 population

2.5 Hospital beds per 1,000 population

131 Hospital discharges per 1,000 population

$4,070 Health care spending per capita

$629 Out-of-pocket health spending per capita

$469 Spending on pharmaceuticals (prescription and OTC) per capita

81.3 Life expectancy at birth (years)

28.7% Obesity prevalence

4.3% Diabetes prevalence

14% Adults with multiple chronic conditions (2 or more)

HEALTH CARE DELIVERY AND PAYMENT

General practitioners (GPs) are generally private contractors in solo or

practices or salaried employees. Payment is a mixture of capitation for essential services, fee-for-service for additional services, and pay-for-performance bonuses. Registration with a GP is required. Patient cost-sharing: None for NHS-covered services, but GPs have the discretion to charge for certain services, such as vaccinations for overseas travel.

Specialists are almost all salaried employees of NHS hospitals, and specialist visits occur in hospitals. Hospitals are paid for most outpatient consultations at nationally determined rates. Some specialists also engage in private practice. Patient cost-sharing: None.

Hospitals are a mix of public (the majority) and some private facilities. Public hospitals contract with the local CCG to provide services and are paid mainly according to nationally determined diagnosis-related group rates. Certain specialized services are commissioned directly by NHS England. Some NHS care is delivered by private hospitals — for example, as an alternative to services that are subject to long wait times, such as elective care. Private hospital charges for private patients are not regulated in the same way or subsidized by the government. Patient cost-sharing: None at public hospitals.

All costs are in U.S. dollars, adjusted for cost-of-living differences.

Conversion rate: USD 1.00 = GBP 0.70.

Prescription drugs provided in hospitals are covered without copayment, as are the majority of outpatient prescriptions. Many patients are exempt from copayments: children, youth ages 16 to 18 in full-time education, adults over 60, individuals and families with low income, and women who are or were recently pregnant. Patient cost-sharing: USD 12.50 per prescription for outpatient drugs. Patients needing large amounts of prescription drugs can buy prepayment certificates costing USD 148 for 12 months.

Mental health care is fully covered under the NHS. Less-serious illnesses, such as mild depression and anxiety, are usually treated by GPs. More advanced treatments, including inpatient care, are provided by specialist mental health trusts or hospital trusts. Some of these services are provided by community-based practitioners. Patientcost-sharing: None.

Long-term care is funded mostly by local authorities and provided mostly by the private sector. The NHS covers some types of long-term care at home or in residential facilities for people with needs arising from illness, disability, or accident. Full state support for long-term residential care requires means-testing. Patient cost-sharing: Those eligible for long-term residential care are liable for copayments. Locally funded social care is not typically free at the point of use.

Safety nets are provided through cost-sharing exemptions. No copays for vision tests for children/youth, older adults, or adults with low incomes. Dental copayments are waived for children/youth, students, women who are or recently were pregnant, people with low income, and others. Transportation costs to and from provider sites also are covered for people who qualify as low-income.

Care coordination is the responsibility of GPs, who are increasingly working in multipartner practices that employ nurses and other clinical staff to monitor patients with chronic conditions. CCGs are also charged with promoting the coordination of local services, particularly at the intersection of hospital and social care. In addition, voluntary integrated care systems bring together local authorities, GP networks, and local hospitals to plan services for defined populations.

TOTAL HEALTH EXPENDITURES

In 2016, the U.K. spent 9.8 percent of GDP on health care, of which nearly 80 percent represented public expenditures

RECENT REFORMS

• The 10-year NHS Long Term Plan, published in 2019, sets out a vision for 1) local integrated care systems to improve population health; 2) new national strategies on cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, cancer, and mental health; and 3) new primary care networks to better link together general practices.

This overview was prepared by Ruth Thorlby.[5]

Health insurance is mandatory in Germany. Approximately 86 percent of the population is enrolled in statutory health insurance (SHI), which provides inpatient, outpatient, mental health, and prescription drug coverage. Administration is handled by nongovernmental insurers known as sickness funds. Government has virtually no role in the direct delivery of health care. Sickness funds are financed through general wage contributions (14.6%) and a dedicated supplementary contribution (1% of wages, on average), both shared by employers and employees, as well as a supplementary income-dependent sum paid by enrollees (1%, on average). Copayments apply to inpatient services and drugs, and sickness funds offer a range of deductibles. Germans earning more than USD 68,000 can opt out of SHI and choose private health insurance instead. There are no government subsidies for private insurance.

H E A LT H SYSTEM OVERVIEW DEMOGRAPHICS

21.4% Population age 65+

CAPACITY & UTILIZATION

4.3 Practicing physicians per 1,000 population

9.9 Average physician visits per person

12.9 Nurses per 1,000 population

8.0 Hospital beds per 1,000 population

255 Hospital discharges per 1,000 population

$5,986 Health care spending per capita

$738 Out-of-pocket health spending per capita

$823 Spending on pharmaceuticals (prescription and OTC) per capita

81.1 Life expectancy at birth (years)

23.6% Obesity prevalence

8.3% Diabetes prevalence

17% Adults with multiple chronic conditions (2 or more)

HEALTH CARE DELIVERY AND PAYMENT (SHI ONLY)

Primary and outpatient specialist physicians typically work in solo (56%) or dual private practices. Fee-for-service payment negotiated between sickness funds and regional provider associations. Quarterly payment caps limit reimbursement to maximum number of patients and treatments per patient. Patient registration with GP generally not required. Physicians cannot charge above fee schedule for covered services. Patient cost-sharing: No fixed fees. No cost-sharing for recommended preventive services.

Specialists are organized and paid as GPs are. Patient cost-sharing: Same as GPs.

Hospitals are a roughly equal mix of public and private, with the latter mostly nonprofit. Inpatient care paid through diagnosis-related groups. Hospitals receive supplementary fees to reimburse costs for highly specialized, expensive services (e.g., chemotherapy) and new technologies. Patient cost-sharing: USD 12.84 copayment per inpatient day, up to USD 359 per year.

All costs are in U.S. dollars, adjusted for cost-of-living differences.

Conversion rate: USD 1.00 = EUR 0.78.

Prescription drugs are covered under SHI except for some exclusions, mostly lifestyle drugs. Patient cost-sharing: 10 percent, or a minimum of USD 6.42, up to a maximum of USD 12.84, or the price of the drug plus the difference between the price and the reference price.

Mental health acute services are provided largely in psychiatric wards in general acute hospitals. Statutory health insurance covers inpatient and ambulatory-based mental health care. Fee-for-service payment is used for ambulatory-based mental health care. Ambulatory psychiatrists coordinate a set of statutory benefits called sociotherapeutic care (which requires referral by a GP), intended to encourage people with chronic mental illness to use necessary care and avoid unnecessary hospitalizations.

Long-term care services are covered separately under mandatory statutory long-term care insurance, funded by 3.05 percent wage contribution (shared by employers and employees). People without children pay an additional 0.25 percent. Home and institutional care delivered mostly by private nonprofit and for-profit providers. Family caregivers receive up to 50 percent of care costs. Patient cost-sharing: Long-term care benefits cover approximately 50 percent of institutional care costs. Beneficiaries can choose between free or discounted long-term care services and cash payments.

Safety nets take the form of cost-sharing caps and exemptions. Children under 18 exempt from cost-sharing. Adults have annual cost-sharing cap equal to 2 percent of household income; lowered to 1 percent for chronically ill people who receive recommended counseling or screenings prior to becoming ill. The unemployed contribute to SHI in proportion to unemployment entitlements. Government covers contribution for long-term unemployed.

Care coordination is encouraged through integrated care contracts and disease management programs aimed at improving coordination among ambulatory providers, particularly for chronically ill patients. The Innovation Fund allocates awards for regional care models that promote integrated care, including those targeting vulnerable groups in rural areas.

TOTAL HEALTH EXPENDITURES

In 2017, total health expenditures accounted for 11.5 percent of GDP; 74 percent of these were publicly funded.

RECENT REFORMS

• New bill aims to reduce mandatory contributions to SHI by splitting supplemental income-dependent sum between enrollees and employers; also addresses financial burden that SHI contributions impose on self-employed and small businesses.

• Nursing Staff Strengthening Act (2018) expanded professional duties of nurses in hospitals and long-term care and reformed nursing salaries and working conditions.

• Minimum staffing ratios for nurses initiated in 2019 apply to intensive care, geriatric, cardiology, and trauma surgery hospital units.

This overview was prepared by Miriam Blumel and Reinhard Busse[6]

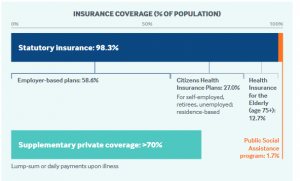

Japan’s statutory health insurance system provides universal coverage. It is funded primarily by taxes and individual contributions. Enrollment in either an employment-based or a residence-based health insurance plan is required. Benefits include hospital, primary, specialty, and mental health care, as well as prescription drugs. In addition to premiums, citizens pay 30 percent coinsurance for most services, and some copayments. Young children and low-income older adults have lower coinsurance rates, and there is an annual household out-of-pocket maximum for health care and long-term services based on age and income. There are also monthly out-of-pocket maximums. The national government sets the fee schedule. Japan’s prefectures develop regional delivery systems. Most residents have private health insurance, but it is used primarily as a supplement to life insurance, providing additional income in case of illness.

H E A LT H SYSTEM OVERVIEW DEMOGRAPHICS

28.2% Population age 65+

CAPACITY & UTILIZATION

2.4 Practicing physicians per 1,000 population

12.6 Average physician visits per person

12.6 Nurses per 1,000 population

13.1 Hospital beds per 1,000 population

128 Hospital discharges per 1,000 population

$4,766 Health care spending per capita

$608 Out-of-pocket health spending per capita

$838 Spending on pharmaceuticals (prescription and OTC) per capita

84.2 Life expectancy at birth (years)

4.4% Obesity prevalence

5.7% Diabetes prevalence

Data: 2019 OECD Health Data except diabetes prevalence from Health at a Glance 2019 (IDF Atlas 2017 data).

HEALTH CARE DELIVERY AND PAYMENT

General practitioners (GPs) are mostly self-employed and work in clinics and hospital outpatient departments. No patient registration required. GPs are paid according to a complex fee-for-service schedule set by the national government. Patient cost-sharing: Usually 30 percent coinsurance.

Specialists typically work in hospital outpatient departments and some clinics. No referral is needed at clinics. Patient cost-sharing: Usually 30 percent coinsurance.

Hospitals are a mix of private and public. They are paid using a case-mix classification system, similar to diagnosis-related groups, or on a fee-for-service basis. In 2016, 15 percent of hospitals were owned by national or local governments or closely related agencies; the rest were private and nonprofit, although they may have received subsidies. Some companies, such as Toyota, have established their own hospitals for employees. Patient cost-sharing: Usually 30 percent coinsurance.

All costs are in U.S. dollars, adjusted for cost-of-living differences.

Conversion rate: USD 1 = JPY 100

Prescription drugs are covered based on clinical effectiveness but not costs.Patient cost-sharing: Usually 30% coinsurance.

Mental health care is provided in outpatient, inpatient, and home care settings. Coverage includes psychological tests and therapies, pharmaceuticals, and rehabilitative activities. Patient cost-sharing: Standard 30% coinsurance.

Long-term care is covered by national compulsory long-term care insurance administered by municipalities. Covered services, delivered mostly by private providers, include home care, respite care, and domiciliary care. Patient cost-sharing:10–20 percent coinsurance for covered services, depending on age and income, up to an income-related ceiling. Depending on income, patients may have an additional copayment for bed and board in institutional care.

Care coordination for patients with cancer, stroke, and cardiac disease is incentivized through additional provider payments. Community comprehensive support centers coordinate services for those with long-term conditions.

TOTAL HEALTH EXPENDITURES

In 2015, total health expenditures represented 11 percent of Japan’s GDP; 84 percent of these were publicly financed, mainly through the statutory health insurance system.

RECENT REFORMS

The Social Security Council set four objectives for its 2018 fee schedule revision:

• developing efficient and comprehensive care in the community

• developing safe, reliable, high-quality care and creating services tailored to emerging needs

• reducing the workload of health care workers

• making the health care system more efficient and sustainable.

In addition to the launch of the Continuous Care Fees program, which makes monthly payments to physicians for providing ongoing care to outpatients with chronic disease, hospital payments are now more differentiated according to staffing density than they were under the previous fee schedule.

This overview was prepared by Ryozo Matsuda.[7]

Watch PBS Newshour special “Health Care: America vs. the World”

- https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/2020-12/2020_IntlOverview_USA.pdf ↵

- https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/2020-12/2020_IntlOverview_AUS.pdf ↵

- https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/2020-12/2020_IntlOverview_CAN.pdf ↵

- https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/2020-12/2020_IntlOverview_SWITZ.pdf ↵

- https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/2020-12/2020_IntlOverview_ENG.pdf ↵

- https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/2020-12/2020_IntlOverview_GER.pdf ↵

- https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/2020-12/2020_IntlOverview_JAPAN.pdf ↵