3 Defining Health and Determinants of Health

In this chapter, we first take a closer look at the concepts of “health” and determinants of health. With this background, you will watch a forty-minute presentation by Dr. Epperly, further exploring the U.S. health system.

Please begin by reading the article by Krahn et al. (2021), discussing various definitions of “health” and the implications of how health is defined.

Article Citation:

Krahn, G. L., Robinson, A., Murray, A. J., & Havercamp, S. M. (2021). It’s time to reconsider how we define health: Perspective from disability and chronic condition. Disability and Health Journal, 14(4). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2021.101129 (Link to PDF)

It’s time to reconsider how we define health: Perspective from disability and chronic condition[1]

Gloria L. Krahn, PhD a, *, Ann Robinson, MPH b

, Alexa J. Murray, MGS c ,

Susan M. Havercamp, PhD d

, The Nisonger RRTC on Health and Function

a Hallie Ford Center, 2635 Campus Drive, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, 97330, USA

b The Ohio State University, 275D McCampbell Hall, 1581 Dodd Drive, Columbus, OH, 43210, USA

c The Ohio State University, 275B McCampbell Hall, 1581 Dodd Drive, Columbus, OH, 43210, USA

d The Ohio State University, 371L McCampbell Hall, 1581 Dodd Drive, Columbus, OH, 43210, USA

Article history:

Received 18 September 2020

Received in revised form 21 May 2021

Accepted 28 May 2021

a b s t r a c t

Our understanding of health has changed substantially since the World Health Organization initially defined health in 1948 as “a state of complete physical, mental and social and well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”. These changes include reconceptualizing health on a continuum rather than as a static state, and adding existential health to physical, mental, and social well-being. Further, good health requires adaptation in coping with stress and is influenced by social, personal and environmental factors. Building on prior work, we propose a reconsidered 2020 definition: “Health is the dynamic balance of physical, mental, social, and existential well-being in adapting to conditions of life and the environment.” Health is dynamic, continuous, multidimensional, distinct from function, and determined by balance and adaptation. This new definition has implications for research, policies, and practice, with particular relevance for health considered within a context of disability and chronic conditions.

What does it mean to be healthy? How do individuals, re-searchers, policymakers, and health professionals consider health, particularly in the context of disabilities and other chronic conditions? How are health and conditions for well-being measured? Consider a young woman with Down syndrome who is a competitive swimmer with passion for her sport, a part-time job at the swimming pool, and who gains meaning in life through her sport and her social relationships. Or consider a high school teacher who manages his bipolar disorder through medication and lifestyle, and enjoys being a father, husband, and member of community groups.To what extent are these individuals experiencing good health despite living with a disability or chronic health condition? These simple questions require complex considerations to arrive at tentative answers.Who defines health and how it is defined significantly impact research, policy, and practice. One’s definition of ealth drives how they understand and address health care and health disparities. Public health and medical researchers may explicitly consider their definition of health to select study variables and health outcomes. Policymakers and health care providers may be more or less explicit in defining health and health outcomes targeted for policy change or clinical intervention. The general public may hold still different definitions. This commentary contends that it is time for an updated, holistic, and explicit definition of health.This definition needs to consider the context of disabilities and chronic conditions, and incorporate the knowledge gained over the past decades. We define disabilities as experienced limitations in body function, activities, or participation in major life activities due to a health condition that occur in the context of one’s environment and are influenced by personal factors. This definition is consistent with the International Classification of unctioning, Disability and Health (ICF) (WHO, 2001). We define chronic diseases as primarily noncommunicable diseases with duration of at least one year that may require ongoing medical attention; and chronic conditions to include long-term disabilities as well as chronic diseases that may or may not be associated with functional limitations.

Health as defined by WHO

An early definition of health still in popular use is that of the World Health Organization (WHO). In 1948, WHO defined health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.“5 For more than 70 years, this definition served as an international standard. At the time, it expanded earlier conceptualizations of health by identifying not just physical health, but also mental and social dimensions. Further, the definition affirmed health as a positive state that is not defined merely by the absence of “disease or infirmity.” However, use of the phrase “not merely” also implied that having a disease or infirmity would preclude good health. At the time this definition was coined, the world was emerging from global warfare. Major causes of mortality were cardiovascular disease, infectious diseases, and cancers. Public health had not yet tackled the issues of smoking, obesity, HIV or racial disparities, and was less aware of the influences of social determinants, chronic conditions, environmental exposures, and genomics, or changes brought about by technologies (e.g., communication, medical equipment, assistive devices, transportation, and modern appliances) in many cultures. Disability was considered equivalent with poor health and as a negative health outcome to be prevented through medical or public health interventions.

Subsequently, in the 1986 Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion, WHO stated that “Health is a resource for everyday life, not the objective of living. Health is a positive concept emphasizing social and personal resources, as well as physical capacities.“7 Importantly, in 2001, WHO differentiated among health, function, and disability.7 The ICF framework conceptualized health conditions, personal factors and environmental factors as influencing disability, where disability was regarded as impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions. According to the ICF, health is distinct from disability, and the disabling process reflects the interaction between features of a person and features of the society in which the person lives (WHO, 2001).1 The ICF framework decouples health from disability and incorporates environmental factors that impact health and functioning e factors such as opportunity structures, societal inequalities, family resources, physical environment, and cultural beliefs. Still, the original WHO view of health is aspirational, in that few can maintain “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being” throughout their life. It contributes to dichotomous thinking about health d one is “healthy” or “unhealthy” rather than experiencing health along a continuum of excellent to poor.

Recent views on health demergence of “balance” and “adaptation”

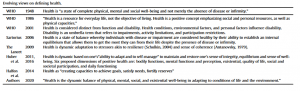

Since then, numerous writers have advanced alternative views that expand our understanding of health (see Table 1). None, however, have offered a new definition of health. Sartorius (2006) proposed conceptualizing health as a dimension that can co-exist with the presence of disease or impairment.8 He summarized three definitions of health in use at the time of his writing: health as 1) absence of disease or infirmity; 2) a state that allows an individual to cope adequately with life demands; and 3) a state of balance or equilibrium established within oneself and with one’s social and physical environment. Sartorius noted the shortcoming of the first definition to be that health remains solely within the purview of medical professionals and does not consider the individual’s perceptions. A limitation of the second definition is that it may miss individuals with health concerns from being considered unhealthy if they appear to be coping “as well as expected,” despite self-reported feelings of being unwell. Sartorius and others 9 advocated for the third definition that considers health a state of balance whereby individuals with disease or impairment are considered healthy by their ability to establish an internal equilibrium that allows them to get the most they can from their life despite the presence of disease or infirmity.

In 2009, in response to scientific advances and global crises, the editors of The Lancet called for a more contemporary view of health that incorporates current understanding of the impacts of genomics, the environment, and planetary health. Drawing on the earlier work of Canguilhem (1943),10 they promoted a dynamic view of health where the idea of perfection (a “complete state”) is replaced with adaptation. This view recognized that environmental and personal factors are not static, but highly dynamic. As examples, war and conflict can tear apart the fabric of social structures;governmental policies can lead to inadequate nutrition or medical care; and loss of livelihood or a spouse can dramatically change one’s economic resources. They contend that a view of health as adaptation opens the possibilities for more compassionate, comforting, and creative health care.11 Other authors further defined adaptation as resonant with the concept of “resilience.“12 Resilience means the ability of a healthy person to regain or maintain balance or “a sense of coherence” in response to physiological 13 or psychological stress.14 Health as achieved through adaptation is a particularly relevant perspective today. Globally, one in three adults live with at least one chronic disease,15,16 with higher rates in older populations and in high income countries, and up to 15% of people live with disability.17,18 Many more people live in turbulent social, interpersonal or economic situations around the globe.

Adding their voice to the call for a revised definition, Huber and colleagues 12 summarized limitations of the WHO 1948 definition. Briefly, these include the concern that “a complete state” of well-being is unattainable for most people; that the 1948 definition fails to address the current demography where many people live with chronic disease; and that the WHO definition is hard to use because “complete” state is neither operational nor measurable. Recognizing that redefining health is ambitious and complex, they nonetheless converged on a dynamic view of health based on the ability to maintain and restore one’s sense of balance and equilibrium as reflected in “the ability to adapt and to self-manage.” In subsequent work, they support six dimensions of health: bodily functions, mental functions and perception, existential health, quality of life, social and societal participation, and daily functioning.19 These dimensions were later affirmed in a meeting of Dutch experts to address reconsideration of the ICF.20

Recent attention to social determinants of health highlights the importance of environmental and social factors on health, such as systemic racism and racial bias, resource poor neighborhoods, and living with chronic stress.21 Halfon and colleagues (2014) applied a life-course health science approach to address the impact of environmental exposures and social experience on biological and behavioral health. They contend that health system reform must consider the life course to understand how prenatal and early childhood events affect later health.22 Similarly, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s “culture of health” promotes a broad view of health that includes overall well-being and incorporates social determinants of health.23 Emerson and colleagues 24 outlined how environments specifially affect the health of people with disabilities while others demonstrate the compounding impact of racism and ableism on health disparities. 33

Reconsidered definition of health

To advance contemporary thinking and informed by our work with people with disabilities, we propose the following working definition: “Health is the dynamic balance of physical, mental, social, and existential well-being in adapting to conditions of life and the environment.

Table 1

” This definition builds upon the work of previous writers and is framed in the context of 2020. This is a time when COVID-19 evidences the global interconnectedness of health, and when adaptation to the rapidly changing context is critical to maintain individual and population health. This updated definition is comprised of six distinct features: health is 1) dynamic, 2) continuous, 3) multidimensional, 4) distinct from functional limitation, 5) determined by balance and adaptation, and 6) influenced by social and other environmental factors.

Health is dynamic and varies along a continuum.

We depart from the notion of an ideal health state of “complete” well-being. We assert that health is dynamic and varies along a continuum. 8,11,12 Health can improve or deteriorate across the life span, either acutely or through gradual progression. Health is also dynamic in how it is influenced by environmental, social, and personal factors. Personal factors include values, expectations, and preferences as well as individual identity and demographic characteristics. 7,8,20 Values, preferences, and expectations are, in turn, influenced by environmental and social factors that include culture, social status, systemic racism, governmental policies and economic circumstances.

The proposed definition affirms the multidimensional nature of health and adds existential well-being to the dimensions of physical, mental and social well-being. Existential well-being refers to a person’s current sense of subjective well-being relating to dimensions such as the meaning or purpose of one’s life, satisfaction in life, and feelings of comfort regarding death and suffering. 25 This dimension has been labeled as “spiritual integrity,” “living one’s values” or “having purpose in life,” and has been proposed for inclusion by other writers.11,12,20

By adding this dimension to health, we recognize the importance of having the freedom to live according to one’s values and religious practices without fear of persecution. Further, the inclusion of existential well being is supported by extensive literature on existential health,26 documentation of existential concerns in clinical and community patient samples, 27 and factor analyses of items in current measures of health-related quality of life support inclusion of this dimension. 28

Health is distinct from function. In the proposed definition, good health can exist in the presence of limitations, such as those associated with disability. We contend that people with disabilities can be healthy. In doing so, we disagree with conceptualizations of health that include function as a measure of health and, instead, endorse WHO and others 7,11,14,24 in regarding health and function as interrelated but distinct constructs. This differentiation of health from function, as indicated by the ICF, is of substantive importance to both disability and health research. From a policy perspective, it allows health systems to be held accountable for promoting the health of persons with disabilities.

Balance through adaptation determines health. Balance is the equilibrium achieved through adaptation within oneself and between oneself and the social and physical environment.8,11,34 Adaptation can be reflected both through making change (e.g.,adjusting personal priorities or modifying lifestyle behaviors) and through accepting change (e.g., accepting “the new normal”). Balance in adapting to life circumstances, including internal and environmental circumstances, determines health.29 Internal circumstances might be disease or injury, while external circumstances might be the acute stress of job loss or the chronic stress of living with structural racism, civil war, or political oppression. As the factors influencing health are often non-medical, applying health care solutions exclusively to these issues is insufficient. Balance requires not only the ability to adapt to internal and external stress, but resources and supports to eliminate barriers. Striving to achieve balance through adaptation is a continual process throughout all stages of a person’s life.

Social and other environmental influences. Health as adaptation is influenced by the social, political and physical features of the environmental context. Gaining access to the resources and supports needed to achieve balance may be limited by public policy and negative social determinants of health.21 Among their many influences, these contexts contribute to observed health disparitiesrelated to systemic racism, 30,31 disability status,32 and the intersection of racism and ableism. 33 They bring attention to the political and policy contexts of strategies to improve health at individual and population levels. A robust literature describes the psychoiological and psychosocial processes of resiliency when individuals adapt or cope successfully. 34,35

The current COVID-19 pandemic illustrates this broader view of health. The global interconnectedness of health is profoundly evident. Maintaining good health requires adapting to rapidly changing contexts that threaten individual physical, emotional, social, and existential well-being. Pre-existing inequities experienced based on race, poverty, and disability are now amplified by current social and environmental circmstances. Outcomes are expressed in increased vulnerability to infection, severity, and deaths. From this view, health is not static but varies along a continuum across the life span. Good health is directly related to settings that promote adaptation and resilience in managing life conditions and the environment.

Implications for measurement of health

Clarity in definition of health is foundational to good health measurement. While the question of how to conceptualize health has prompted critical discourse, there has been less attention given to updating its measurement. Health research and population monitoring often lack an explicit definition or conceptualization of health. As a result, the terms “health status,” “health-related quality of life,” and “quality of life” have been used interchangeably, and measures vary tremendously in their item content. 36,37

When health is defined as balance in adapting to life events, it requires assessment of both process and outcome. Health as a process invites new ways of assessing resiliency and resources for adaptation. It demands attention to the settings in which people strive to become and stay healthy.

Health outcomes measurement occurs at multiple levels. In individual clinical contexts, assessments are more extensive and relate to symptoms and biological metrics with sufficient sensitivty to assess change at the individual level. In research-based comparison studies, measures need to detect change at a group level. In population monitoring, survey measures may consist of a few questions to detect change across time or populations.

Defining health as balance in adapting to life events promotes use of self-report measures to assess health status relative to one’s life situation. This is information that only the individual can provide. 38 The importance of self-perception in assessing health has been reinforced in the literature on self-rated health 32,39 and health-related quality of life.40 Self-report or patient-reported outcomes provide standardized assessments of how individuals function or feel with respect to their health, quality of life, mental well-being, or health care experience.41 Best practice recommendations call for use of self-reported outcome measures in conjunction with physiological (e.g. laboratory and diagnostic) measures.

In times of medical scarcity, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, ethical decisions about allocating critical care resources must be based on individual assessments of whether the patient is likely to benefit from treatment. 42 In practice, many states and hospital systems developed crisis plans that based triage decisions on quality of life judgements or excluded patients with certain conditions that constitute disabilities.43,44 Such judgements are vulnerable to pervasive negative biases and inaccurate assumptions about the quality of life of people with disability.45 Scoring systems using quality-adjusted-life-years (QALY) or disability-adjusted-life-years (DALY) overtly discriminate against people with disabilities by assuming that a year in the life of a person with a disability is worth less than a year of an able-bodied person. 43,44 This is because the QALY calculation reduces the value of treatments that do not bring a person back to “perfect health,” in the sense of not having a disability and meeting society’s definitions of “healthy” and “functioning.“46

Implications for practice and policy

For health policy and practice, the proposed definition draws greater attention to the multiple dimensions of health and fosters new questions. Do interventions embrace a multi-dimensional view of health and attend to the environmental context? For researchers, do the measures of health align with the presumed definition of health? In health care delivery, do outcome measures reflect what is important to the patient? In times of strained health care systems, are policies and decisions equitable for patients across marginalized groups? And for health care payers, what are the costs and benefits of expanding coverage to services that support adaptation to personal conditions and environment? Such questions can lead to new lines of research inquiry and policy development that advance health equity and improved population health.

Definitions of health and opportunities for achieving good health are inherently political. Across time and countries, determining what constitutes good health and who is eligible for health services are influenced by governmental decisions and political advocacy. This proposed working definition of health is intended to be universally useful across countries and contexts. As such, it establishes a common understanding of health that emphasizes active adaptation, including continual adaption across the lifespan to disabilities or chronic diseases. This definition requires us to recognize contributors to health inequities experienced by people who are marginalized in society. It speaks to expansion of health benefits and policies that improve access to the social supports and resources needed by individuals to adapt to their circumstances. For example, people with disabilities experience barriers in accessing quality health care, prejudicial attitudes to their full participation in employment and community life, and limited opportunities to engage in healthy behaviors that contribute to significant health disparities.24,32

When national health care policy focuses on all of its people, the priorities become optimizing health through access to preventive health and medical care (including vaccines), healthy environments and economies, and supports to adapt to the conditions of life and environment. Because of the interconnectedness of health with nutrition, housing, transportation, and other aspects of community living, policy at multiple levels can have great impact on the health of people with disabilities.

Summary

While the 1948 WHO definition of health has been widely adopted and influential for many decades, concerns have been raised around its utility for contemporary research and understanding. Modifications have been proposed by numerous experts, leading to this call to reconsider how health is defined. We propose a working 2020 definition: “Health is the dynamic balance of physical, mental, social, and existential well-being in adapting to conditions of life and the environment.” This reconsidered definition of health is intended to stimulate discourse on how health is conceptualized and its implications for research, policy, and practice that can address health disparities among marginalized groups. This definition incorporates environmental factors and recognizes health as fluid across the life span, with adaptation to life circumstance at its core.

Can a competitive swimmer with Down syndrome or a high school teacher with bipolar disorder experience good health? Yes. When health is disconnected from limitations, both individuals are currently experiencing good health and purpose in their lives because they have found ways to adapt to their situations using internal and external resources. However, the dynamic nature of health means it can change at any time, especially if one or more dimensions are disrupted by internal or external factors. With public swimming pools closed due to COVID, or changes in medications dictated by health plan coverage, each person will have to adapt in order to reaffirm their sense of balance and health. Because life continually requires us to adapt to stressors, social contexts and supports are vital to maintaining good health. The proposed definition of health brings attention to society’s role in generating policies, programs, and research that facilitate successful adaptation across health dimensions throughout life, in particular for people with disabilities and chronic conditions.

Funding

The contents of this Commentary were developed as par of a Rehabilitation Research and Training Center (RRTC) on Health and Function awarded to The Ohio State University (OSU) Nisonger Center through a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90RTHF0002-01-00). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

Disclaimer

The contents of this Commentary do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, or HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government.

Conflicts of interest

Authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

1. World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF); 2001. Published online https://www.who.int/classifications/ icf/en/.

2. Bernell S, Howard SW. Use your words carefully: what is a chronic disease? Front Public Health. 2016;4:159. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2016.00159, 2016 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4969287.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About chronic diseases. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov /chronicdisease/about/index.htm#:~:text¼Chronic% 20diseases%20are%20defined%20broadly,disability%20in%20the%20United% 20States; 2019.

4. World Health Organization. Preventing Chronic Diseases: A Vital Investment; 2005. ISBN 92 4 156300 1 Available at: https://www.who.int/chp/chronic_disease_report/full_report.pdf.

5. World Health Organization. WHO constitution. Published online https://www. who.int/about/who-we-are/constitution; 1948.

6. Taylor R, Lewis M, Powles J. The Australian mortality decline: cause-specific mortality 1907-1990. Aust N Z J Publ Health. 1998;22(1):37e44. https:// doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-842X.1998.tb01142.x.

7. World Health Organization. The Ottawa charter for health promotion. Published online https://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/ottawa/en/; 1986.

8. Sartorius N. The meanings of health and its promotion. Croat Med J. 2006;47(4): 662e664.

9. Wagner AK. Where do biomarkers fit when trying to relate health to function?. The Use of Biomarkers to Establish Presence and Severity of Impairments. A Work-shop; 2020. https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/03-30-2020/the-use-of-biomarkers-to-establish-presence-and-severity-of-impairments-a-workshop.

10. Canguilhem G. On the Normal and the Pathological. Zone Books; 1943.

11. The Lancet. What is health? The ability to adapt. Lancet. 2009;373(9666):781. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60456-6.

12. Huber M, Knottnerus JA, Green L, et al. How should we define health? BMJ. 2011;343(jul26 2). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d4163. d4163-d4163.

13. Allostasis Schulkin J. Homeostasis, and the Costs of Physiological Adaptation. Cambridge University Press; 2004.

14. Antonovsky A Health. Stress and Coping. Jossey-Bass; 1979.

15. Buttorff C, Ruder T, Bauman M, , RAND Health, Health Services Delivery Systems, Rand Corporation. Multiple Chronic Conditions in the United States. 2017.

16. Hajat C, Stein E. The global burden of multiple chronic conditions: a narrative review. Prev Med Rep. 2018;12:284e293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.10.008. . Accessed October 19, 2018.

17. Courtney-Long EA, Carroll DD, Zhang QC, et al. Prevalence of disability and disability type among adults–United States, 2013. Morb Mortal Wkly Rev. 2015;64(29):777e783.

18. World Health Organization and The World Bank. World Report on Disability. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011.

19. Huber M, van Vliet M, Giezenberg M, et al. Towards a ‘patient-centred’ operationalisation of the new dynamic concept of health: a mixed methods study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(1), e010091. https://doi.org/10.1136 /bmjopen-2015-010091.

20. Heerkens YF, de Weerd M, Huber M, et al. Reconsideration of the scheme of the international classification of functioning, disability and health: incentives from The Netherlands for a global debate. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(5):603e611. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2016.1277404.

21. Palmer RC, Ismond D, Rodriquez EJ, Kaufman JS. Social determinants of health: future directions for health disparities research. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(S1):S70eS71. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.304964.

22. Halfon N, Long P, Chang DI, Hester J, Inkelas M, Rodgers A. Applying a 3.0 transformation framework to guide large-scale health system reform. Health Aff. 2014;33(11):2003e2011. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0485.

23. Weil AR. Building a culture of health. Health Aff. 2016;35(11):1953e1958. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0913.

24. Emerson E, Madden R, Graham H, Llewellyn G, Hatton C, Robertson J. The health of disabled people and the social determinants of health. Publ Health. 2011;125(3):145e147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2010.11.003.

25. Ownsworth T, Nash K. Existential well-being and meaning making in the context of primary brain tumor: conceptualization and implications for intervention. Front Oncol. 2015;5:96. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2015.00096. .Accessed April 27, 2015.

26. la Cour P, Hvidt NC. Research on meaning-making and health in secular society: secular, spiritual and religious existential orientations. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(7):1292e1299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soscimed.2010.06.024.

27. Robin Cohen S, Mount BM, Bruera E, Provost M, Rowe J, Tong K. Validity of the McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire in the palliative care setting: a multicentre Canadian study demonstrating the importance of the existential domain. Palliat Med. 1997;11(1):3e20. https://doi.org/10.1177/026921639701100102.

28. Krahn GL, Horner-Johnson W, Hall TA, et al. Development and psychometric assessment of the function-neutral health-related quality of life measure. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;93(1):56e74. https://doi.org /10.1097/ PHM.0b013e3182a517e6.

29. Lipworth WL, Hooker C, Carter SM. Balance, balancing, and health. Qual Health Res. 2011;21(5):714e725. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732311399781.

30. Institute of medicine. Unequal Treatment. What Healthcare Providers Need to Know about Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health-Care. National Academy Press; 2002. http://www.nap.edu/catalog/10260.html.

31. Colen CG, Ramey DM, Cooksey EC, Williams DR. Racial disparities in health among nonpoor African Americans and Hispanics: the role of acute and chronic discrimination. Soc Sci Med. 2018;199:167e180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.04.051.

32. Krahn GL, Walker DK, Correa-De-Araujo R. Persons with disabilities as an unrecognized health disparity population. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(S2):S198eS206. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302182.

33. Breslin ML, Goode TD, Havercamp S, et al. Compounded Disparities: Health Equity at the Intersection of Disability, Race and Ethnicity; 2018. https://dredf.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Compounded-Disparities-Intersection-of-Disabilities-Race-and-Ethnicity.pdf.

34. Charney DS. Psychobiological mechanisms of resilience and vulnerability: implications for successful adaptation to extreme stress. Aust J Pharm. –2004;161(2):195e216. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.161.2.195.

35. Reich JW, Zautra AJ, Hall JS, eds. Handbook of Adult Resilience. Guilford Press; 2010.

36. Hall T, Krahn GL, Horner-Johnson W, Lamb G. The rehabilitation research and training center expert panel on health measurement. Examining functional content in widely used health-related quality of life scales. Rehabil Psychol. 2011;56(2):94e99. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023054.

37. Karimi M, Brazier J. Health, health-related quality of life, and quality of life: what is the difference? Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34(7):645e649. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-016-0389-9.

38. Lavallee DC, Chenok KE, Love RM, et al. Incorporating patient-reported out-comes into health care to engage patients and enhance care. Health Aff. 2016;35(4):575e582. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1362.

39. Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav. 1997;38(1):21e37.

40. Anderson KL, Burckhardt CS. Conceptualization and measurement of quality of life as an outcome variable for health care intervention and research. J Adv Nurs. 1999;29(2):298e306. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.00889.x.

41. Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005e2008. J Clin Epidemiol.2010;63(11):1179e1194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011.

42. HHS Office for Civil Rights. Bulletin: civil rights, HIPAA, and the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Published March 28, 2020 https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/ocr-bulletin-3-28-20.pdf. Accessed November 15, 2020.

43. Mello MM, Persad G, White DB. Respecting disability rights – toward improved crisis standards of care. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(5):e26. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2011997.

44. Solomon MZ, Wynia MK, Gostin LO. COVID-19 crisis triage – optimizing health outcomes and disability rights. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(5):e27. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2008300.

45. National Council on Disability. Medical futility and disability bias. Published November 20, 2019 https://ncd.gov/sites/default/files/NCD_Medical_Futility_Report_508.pdf. Accessed November 15, 2020.

46. National Council on Disability. Quality-adjusted life years and the devaluation of life with a disability. Accessed November 15, 2020 https://ncd.gov/sites/default/files /NCD_Quality_Adjusted_Life_Report_508.pdf; 2019, 6, 11.

Next, please read the following overview of social determinants of health from the HealthyPeople 2020 webpage.

Healthy People 2020 Social Determinants of Health[2]

Goal

Create social and physical environments that promote good health for all.

Overview

Health starts in our homes, schools, workplaces, neighborhoods, and communities. We know that taking care of ourselves by eating well and staying active, not smoking, getting the recommended immunizations and screening tests, and seeing a doctor when we are sick all influence our health. Our health is also determined in part by access to social and economic opportunities; the resources and supports available in our homes, neighborhoods, and communities; the quality of our schooling; the safety of our workplaces; the cleanliness of our water, food, and air; and the nature of our social interactions and relationships. The conditions in which we live explain in part why some Americans are healthier than others and why Americans more generally are not as healthy as they could be.

Healthy People 2020 highlights the importance of addressing the social determinants of health by including “Create social and physical environments that promote good health for all” as one of the four overarching goals for the decade.1 This emphasis is shared by the World Health Organization, whose Commission on Social Determinants of Health in 2008 published the report, Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health.2 The emphasis is also shared by other U.S. health initiatives such as the National Partnership for Action to End Health Disparities 3 and the National Prevention and Health Promotion Strategy.4

The Social Determinants of Health topic area within Healthy People 2020 is designed to identify ways to create social and physical environments that promote good health for all. All Americans deserve an equal opportunity to make the choices that lead to good health. But to ensure that all Americans have that opportunity, advances are needed not only in health care but also in fields such as education, childcare, housing, business, law, media, community planning, transportation, and agriculture. Making these advances involves working together to:

- Explore how programs, practices, and policies in these areas affect the health of individuals, families, and communities.

- Establish common goals, complementary roles, and ongoing constructive relationships between the health sector and these areas.

- Maximize opportunities for collaboration among Federal-, state-, and local-level partners related to social determinants of health.

Understanding Social Determinants of Health

Social determinants of health are conditions in the environments in which people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks. Conditions (e.g., social, economic, and physical) in these various environments and settings (e.g., school, church, workplace, and neighborhood) have been referred to as “place.”5 In addition to the more material attributes of “place,” the patterns of social engagement and sense of security and well-being are also affected by where people live. Resources that enhance quality of life can have a significant influence on population health outcomes. Examples of these resources include safe and affordable housing, access to education, public safety, availability of healthy foods, local emergency/health services, and environments free of life-threatening toxins.

Understanding the relationship between how population groups experience “place” and the impact of “place” on health is fundamental to the social determinants of health—including both social and physical determinants.

Examples of social determinants include:

- Availability of resources to meet daily needs (e.g., safe housing and local food markets)

- Access to educational, economic, and job opportunities

- Access to health care services

- Quality of education and job training

- Availability of community-based resources in support of community living and opportunities for recreational and leisure-time activities

- Transportation options

- Public safety

- Social support

- Social norms and attitudes (e.g., discrimination, racism, and distrust of government)

- Exposure to crime, violence, and social disorder (e.g., presence of trash and lack of cooperation in a community)

- Socioeconomic conditions (e.g., concentrated poverty and the stressful conditions that accompany it)

- Residential segregation

- Language/Literacy

- Access to mass media and emerging technologies (e.g., cell phones, the Internet, and social media)

- Culture

Examples of physical determinants include:

- Natural environment, such as green space (e.g., trees and grass) or weather (e.g., climate change)

- Built environment, such as buildings, sidewalks, bike lanes, and roads

- Worksites, schools, and recreational settings

- Housing and community design

- Exposure to toxic substances and other physical hazards

- Physical barriers, especially for people with disabilities

- Aesthetic elements (e.g., good lighting, trees, and benches)

By working to establish policies that positively influence social and economic conditions and those that support changes in individual behavior, we can improve health for large numbers of people in ways that can be sustained over time. Improving the conditions in which we live, learn, work, and play and the quality of our relationships will create a healthier population, society, and workforce.

Healthy People 2020 Approach to Social Determinants of Health

A “place-based” organizing framework, reflecting five (5) key areas of social determinants of health (SDOH), was developed by Healthy People 2020.

These five key areas (determinants) include:

- Economic Stability

- Education

- Social and Community Context

- Health and Health Care

- Neighborhood and Built Environment

Each of these five determinant areas reflects a number of key issues that make up the underlying factors in the arena of SDOH.

- Economic Stability

- Employment

- Food Insecurity

- Housing Instability

- Poverty

- Education

- Early Childhood Education and Development

- Enrollment in Higher Education

- High School Graduation

- Language and Literacy

- Social and Community Context

- Civic Participation

- Discrimination

- Incarceration

- Social Cohesion

- Health and Health Care

- Access to Health Care

- Access to Primary Care

- Health Literacy

- Neighborhood and Built Environment

- Access to Foods that Support Healthy Eating Patterns

- Crime and Violence

- Environmental Conditions

- Quality of Housing

This organizing framework has been used to establish an initial set of objectives for the topic area as well as to identify existing Healthy People objectives (i.e., in other topic areas) that are complementary and highly relevant to social determinants. It is anticipated that additional objectives will continue to be developed throughout the decade.

In addition, the organizing framework has been used to identify an initial set of evidence-based resources and other examples of how a social determinants approach is or may be implemented at a state and local level.

Emerging Strategies To Address Social Determinants of Health

A number of tools and strategies are emerging to address the social determinants of health, including:

- Use of Health Impact Assessments to review needed, proposed, and existing social policies for their likely impact on health6

- Application of a “health in all policies” strategy, which introduces improved health for all and the closing of health gaps as goals to be shared across all areas of government4, 7

References

1Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives for 2020. Healthy People 2020: An Opportunity to Address the Societal Determinants of Health in the United States. July 26, 2010. Available from: http://www.healthypeople.gov/2010/hp2020/advisory/SocietalDeterminantsHealth.htm

2World Health Organization, Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Available from: http://www.who.int/social_determinants/en

3National Partnership for Action: HHS Action Plan to Reduce Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 2011; and The National Stakeholder Strategy for Achieving Health Equity, 2011. Available from: http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/npa

4The National Prevention and Health Promotion Strategy. The National Prevention Strategy: America’s Plan for Better Health and Wellness, June 2011. Available from: https://www.surgeongeneral.gov/priorities/prevention/strategy/index.html

5The Institute of Medicine. Disparities in Health Care: Methods for Studying the Effects of Race, Ethnicity, and SES on Access, Use, and Quality of Health Care, 2002.

6Health Impact Assessment: A Tool to Help Policy Makers Understand Health Beyond Health Care. Annual Review of Public Health 2007;28:393-412. Retrieved October 26, 2010. Available from: http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.083006.131942

7European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. Health in All Policies: Prospects and potentials, 2006. Accessed on June 16, 2011. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/109146/E89260.pdf [PDF – 1.23 MB]

The Fractured Health Care System: Presentation by Dr. Ted Epperly Video

This 42-minute presentation by Dr. Ted Epperly provides a good overview of many aspects of the way the health system is evolving both in Idaho and around the United States. This presentation was given at St. Luke’s Health System’s 2013 research conference. Although Dr. Epperly covers a range of concepts in his presentation, he does a very good job of breaking concepts down in ways that are easily understandable. Dr. Epperly is the CEO and President of the Family Medicine Residency of Idaho.

If video doesn’t appear, follow this direct link: The Fractured Health Care System: Presentation by Dr. Ted Epperly (41:59 min.)

Use the direct link above to open the video in YouTube to display the video captions and expand the video. To access the transcript for this video, please use

The Fractured Health Care System: Presentation by Dr. Ted Epperly video transcript