In this topic, you begin by reading the first section of the Commonwealth Fund’s profile of the United States health system. This introductory section provides a concise general overview of the U.S. health system as it currently stands. In the next topic, you will read the remaining sections 2-8 of this profile, which discuss specific aspects of the health delivery system in greater depth.

United States Health Profile

Section 1

By The Commonwealth Fund[1]

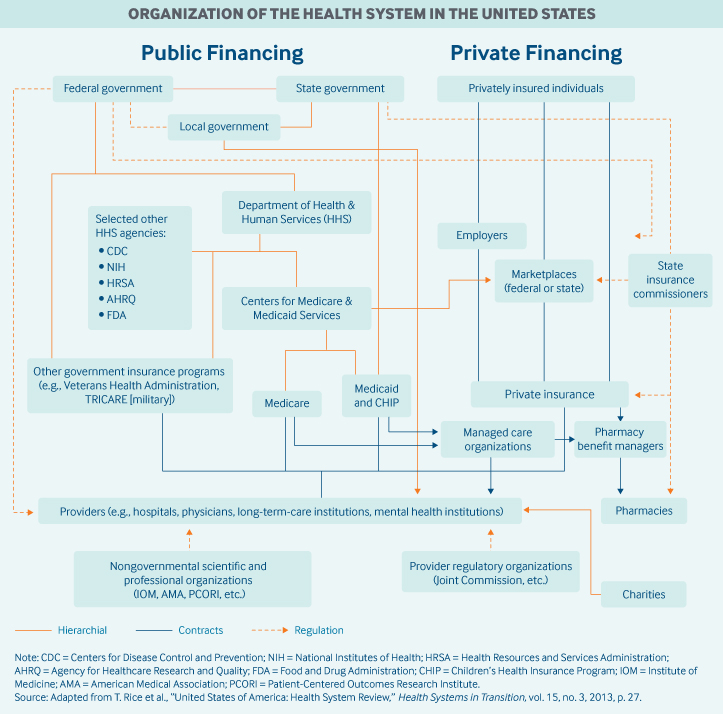

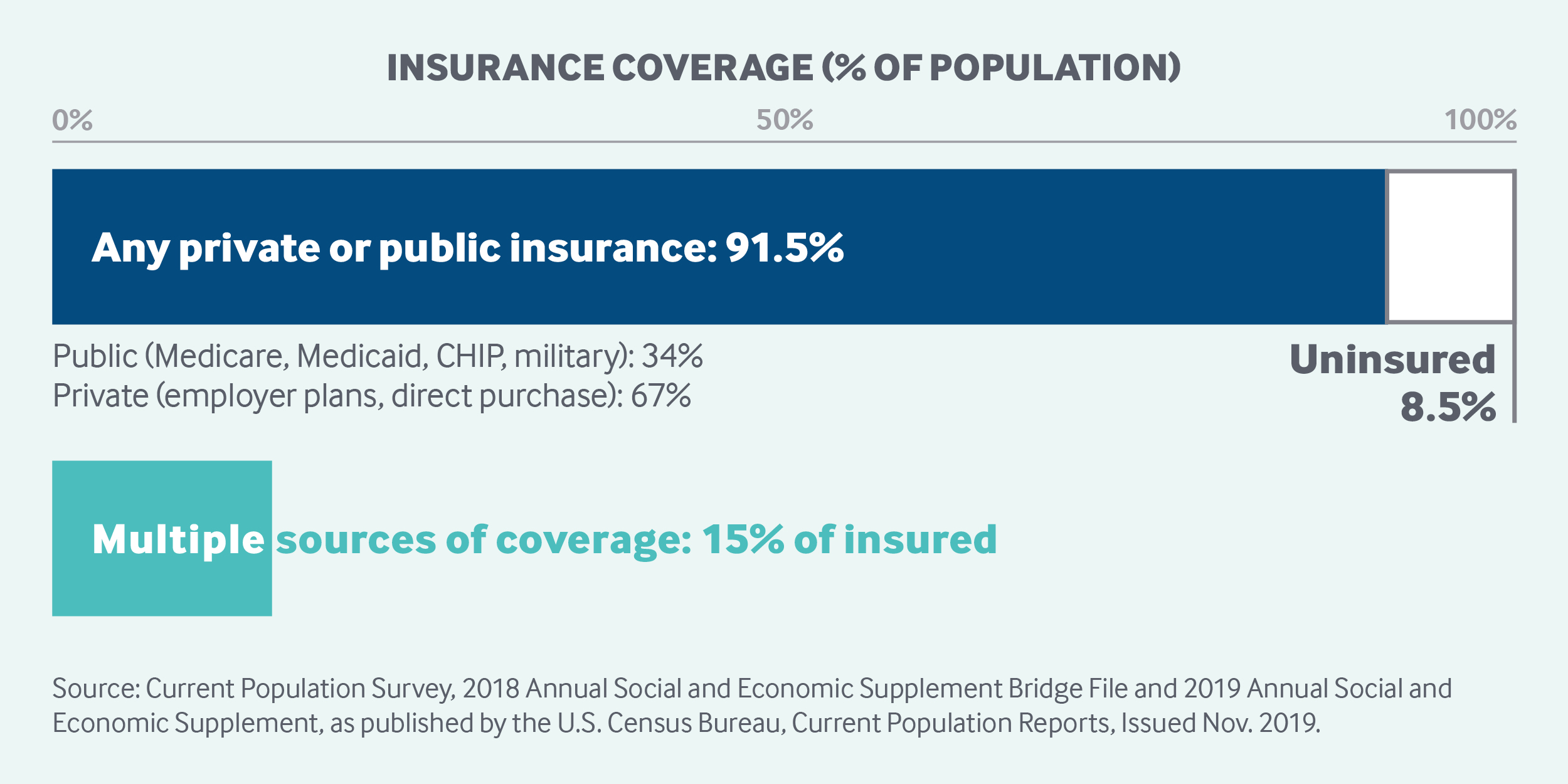

The U.S. health system is a mix of public and private, for-profit and nonprofit insurers and health care providers. The federal government provides funding for the national Medicare program for adults age 65 and older and some people with disabilities as well as for various programs for veterans and low-income people, including Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program. States manage and pay for aspects of local coverage and the safety net. Private insurance, the dominant form of coverage, is provided primarily by employers. The uninsured rate, 8.5 percent of the population, is down from 16 percent in 2010, the year that the landmark Affordable Care Act became law. Public and private insurers set their own benefit packages and cost-sharing structures, within federal and state regulations.

How does universal health coverage work?

The United States does not have universal health insurance coverage. Nearly 92 percent of the population was estimated to have coverage in 2018, leaving 27.5 million people, or 8.5 percent of the population, uninsured.1 Movement toward securing the right to health care has been incremental.2

Employer-sponsored health insurance was introduced during the 1920s. It gained popularity after World War II when the government imposed wage controls and declared fringe benefits, such as health insurance, tax-exempt. In 2018, about 55 percent of the population was covered under employer-sponsored insurance.3

In 1965, the first public insurance programs, Medicare and Medicaid, were enacted through the Social Security Act, and others followed.

Medicare. Medicare ensures a universal right to health care for persons age 65 and older. Eligible populations and the range of benefits covered have gradually expanded. In 1972, individuals under age 65 with long-term disabilities or end-stage renal disease became eligible.

All beneficiaries are entitled to traditional Medicare, a fee-for-service program that provides hospital insurance (Part A) and medical insurance (Part B). Since 1973, beneficiaries have had the option to receive their coverage through either traditional Medicare or Medicare Advantage (Part C), under which people enroll in a private health maintenance organization (HMO) or managed care organization.

In 2003, Part D, a voluntary outpatient prescription drug coverage option provided through private carriers, was added to Medicare coverage.

Medicaid. The Medicaid program first gave states the option to receive federal matching funding for providing health care services to low-income families, the blind, and individuals with disabilities. Coverage was gradually made mandatory for low-income pregnant women and infants, and later for children up to age 18.

Today, Medicaid covers 17.9 percent of Americans. As it is a state-administered, means-tested program, eligibility criteria vary by state. Individuals need to apply for Medicaid coverage and to re-enroll and recertify annually. As of 2019, more than two-thirds of Medicaid beneficiaries were enrolled in managed care organizations.4

Children’s Health Insurance Program. In 1997, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, or CHIP, was created as a public, state-administered program for children in low-income families that earn too much to qualify for Medicaid but that are unlikely to be able to afford private insurance. Today, the program covers 9.6 million children.5 In some states, it operates as an extension of Medicaid; in other states, it is a separate program.

Affordable Care Act. In 2010, the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, or ACA, represented the largest expansion to date of the government’s role in financing and regulating health care. Components of the law’s major coverage expansions, implemented in 2014, included:

- requiring most Americans to obtain health insurance or pay a penalty (the penalty was later removed)

- extending coverage for young people by allowing them to remain on their parents’ private plans until age 26

- opening health insurance marketplaces, or exchanges, which offer premium subsidies to lower- and middle-income individuals

- expanding Medicaid eligibility with the help of federal subsidies (in states that chose this option).

The ACA resulted in an estimated 20 million gaining coverage, reducing the share of uninsured adults aged 19 to 64 from 20 percent in 2010 to 12 percent in 2018.6

Role of government: The federal government’s responsibilities include:

- setting legislation and national strategies

- administering and paying for the Medicare program

- cofunding and setting basic requirements and regulations for the Medicaid program

- cofunding CHIP

- funding health insurance for federal employees as well as active and past members of the military and their families

- regulating pharmaceutical products and medical devices

- running federal marketplaces for private health insurance

- providing premium subsidies for private marketplace coverage.

The federal government has only a negligible role in directly owning and supplying providers, except for the Veterans Health Administration and Indian Health Service. The ACA established “shared responsibility” among government, employers, and individuals for ensuring that all Americans have access to affordable and good-quality health insurance. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services is the federal government’s principal agency involved with health care services.

The states cofund and administer their CHIP and Medicaid programs according to federal regulations. States set eligibility thresholds, patient cost-sharing requirements, and much of the benefit package. They also help finance health insurance for state employees, regulate private insurance, and license health professionals. Some states also manage health insurance for low-income residents, in addition to Medicaid.

Role of public health insurance: In 2017, public spending accounted for 45 percent of total health care spending, or approximately 8 percent of GDP. Federal spending represented 28 percent of total health care spending. Federal taxes fund public insurance programs, such as Medicare, Medicaid, CHIP, and military health insurance programs (Veteran’s Health Administration, TRICARE). The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services is the largest governmental source of health coverage funding.

Medicare is financed through a combination of general federal taxes, a mandatory payroll tax that pays for Part A (hospital insurance), and individual premiums.

Medicaid is largely tax-funded, with federal tax revenues representing two-thirds (63%) of costs, and state and local revenues the remainder.7 The expansion of Medicaid under the ACA was fully funded by the federal government until 2017, after which the federal funding share gradually decreased to 90 percent.

CHIP is funded through matching grants provided by the federal government to states. Most states (30 in 2018) charge premiums under that program.

Role of private health insurance: Spending on private health insurance accounted for one-third (34%) of total health expenditures in 2018. Private insurance is the primary health coverage for two-thirds of Americans (67%). The majority of private insurance (55%) is employer-sponsored, and a smaller share (11%) is purchased by individuals from for-profit and nonprofit carriers.

Most employers contract with private health plans to administer benefits. Most employer plans cover workers and their dependents, and the majority offer a choice of several plans.8,9 Both employers and employees typically contribute to premiums; much less frequently, premiums are fully covered by the employer.

The ACA introduced a federal marketplace, HealthCare.gov, for purchasing individual primary health insurance or dental coverage through private plans. States can also set up their own marketplaces.

More than one in three Medicare beneficiaries in 2019 opted to receive their coverage through a private Medicare Advantage health plan.10

Medicaid beneficiaries may receive their benefits through a private managed care organization, which receives capitated, typically risk-adjusted payments from state Medicaid departments. More than two-thirds of Medicaid beneficiaries are enrolled in managed care.

Services covered: There is no nationally defined benefit package; covered services depend on insurance type:

Medicare. People enrolled in Medicare are entitled to hospital inpatient care (Part A), which includes hospice and short-term skilled nursing facility care.

Medicare Part B covers physician services, durable medical equipment, and home health services. Medicare covers short-term post-acute care, such as rehabilitation services in skilled nursing facilities or in the home, but not long-term care.

Part B covers only very limited outpatient prescription drug benefits, including injectables or infused drugs that need to be administered by a medical professional in an office setting. Individuals can purchase private prescription drug coverage (Part D).

Coverage for dental and vision services is limited, with most beneficiaries lacking dental coverage.11

Medicaid. Under federal guidelines, Medicaid covers a broad range of services, including inpatient and outpatient hospital services, long-term care, laboratory and diagnostic services, family planning, nurse midwives, freestanding birth centers, and transportation to medical appointments.

States may choose to offer additional benefits, including physical therapy, dental, and vision services. Most states (39, as of 2018) provide dental coverage.12

Outpatient prescription drugs are an optional benefit under federal law; however, currently all states provide drug coverage.

Private insurance. Benefits in private health plans vary. Employer health coverage usually does not cover dental or vision benefits.13

The ACA requires individual marketplace and small-group market plans (for firms with 50 or fewer employees) to cover 10 categories of “essential health benefits”:

- ambulatory patient services (doctor visits)

- emergency services

- hospitalization

- maternity and newborn care

- mental health services and substance use disorder treatment

- prescription drugs

- rehabilitative services and devices

- laboratory services

- preventive and wellness services and chronic disease management

- pediatric services, including dental and vision care.

Cost-sharing and out-of-pocket spending: In 2018, households financed roughly the same share of total health care costs (28%) as the federal government. Out-of-pocket spending represented approximately one-third of this, or 10 percent of total health expenditures. Patients usually pay the full cost of care up to a deductible; the average for a single person in 2018 was $1,846. Some plans cover primary care visits before the deductible is met and require only a copayment.

Out-of-pocket spending is considerable for dental care (40% of total spending) and prescribed medicines (14% of total spending).14

Safety nets: In addition to public insurance programs, including Medicare and Medicaid, taxpayer dollars fund several programs for uninsured, low-income, and vulnerable patients. For instance, the ACA increased funding to federally qualified health centers, which provide primary and preventive care to more than 27 million underserved patients, regardless of ability to pay. These centers charge fees based on patients’ income and provide free vaccines to uninsured and underinsured children.15

To help offset uncompensated care costs, Medicare and Medicaid provide disproportionate-share payments to hospitals whose patients are mostly publicly insured or uninsured. State and local taxes help pay for additional charity care and safety-net programs provided through public hospitals and local health departments.

In addition, uninsured individuals have access to acute care through a federal law that requires most hospitals to treat all patients requiring emergency care, including women in labor, regardless of ability to pay, insurance status, national origin, or race. As a consequence, private providers are a significant source of charity and uncompensated care.