12 Value-based Care and the Future of US Healthcare

In this topic, we will first look at some key challenges for U.S. healthcare in the coming decades. We will then take a closer look at value-based care models. By this point in the class, you can hopefully appreciate that the evolution away from fee-for-service (FFS) to value-based payment and care delivery represents a major transition in American health care delivery. And having a solid understanding of value-based care will be necessary to understand how the health system works in the come years.

Specifically, you will first be assigned to watch a video discussing the shift of value-based care in the United States and to read the glossary of terms accompanying this video. You will then read several excerpts from a 2017 report from the National Academy of Medicine (formerly known as the Institute of Medicine) discussing challenges facing American healthcare in the future and strategies to address them.

Read the Glossary of Terms and watch the video “The Fundamental Shift to Value-Based Care.”

For this activity, please begin by reading this 9-page glossary (alternative link) of terms from the CMS Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovations (CMMI). This list provides definitions of key terms used in the videos presented below, many of which you have already encountered in this class. But it also covers a range of key terms related to health care finance, so this glossary of terms is a helpful resource in and of itself. Additionally, however, by first reading this glossary of terms, you will better understand the concepts presented in the video and the subsequent readings for this topic.

Please begin by watching this 20-minute video “The Fundamental Shift to Value-Based Care“. As you will see, this video is part one in a three-part series developed by the CMS Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation. You are only assigned to watch this first video, which summarizes the concept of value-based care, the problems created by fee-for-service reimbursement, and how the U.S. health delivery system is transitioning to a value-based approach to care delivery. The intended audience for this video is practicing physicians, so please carefully review the glossary provided above to make sure you understand all of the terms used in this video.

Read excerpts from Vital Directions for Health Care 2017 report from the National Academy of Medicine

Below are excerpts from two papers that were incorporated National Academcy of Medicine’s 2017 Vital Directions for Health and Healthcare Initiative. Through this initiative, the National Academy of Medicine “drew on more than 150 experts from across the country who authored expert, peer-reviewed papers with policy recommendations in 19 key areas important to three areas: better health and well-being, high-value health care, and strong science and technology.” Below are excerpts from two of these papers. If you are interested in further understanding challenges and proposed solutions regarding various aspects of the U.S. health delivery system, you can access the entire 2017 Vital Directions special report.

Read excerpts from by Dzau et al. (2017) “Vital directions for health and healthcare”

- Dzau, V. J., M. McClellan, S. Burke, M. J. Coye, T. A. Daschle, A. Diaz, W. H. Frist, M. E. Gaines, M. A. Hamburg, J. E. Henney, S. Kumanyika, M. O. Leavitt, J. M. McGinnis, R. Parker, L. G. Sandy, L. D. Schaeffer, G. D. Steele, P. Thompson, and E. Zerhouni. 2017. Vital Directions for Health and Health Care: Priorities from a National Academy of Medicine Initiative. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.31478/201703e

The United States is poised at a critical juncture in health and health care. Powerful new insights are emerging on the potential of disease and disability, but the translation of that knowledge to action is hampered by debate focused on elements of the Affordable Care Act that, while very important, will have relatively limited impact on the overall health of the population without attention to broader challenges and opportunities. The National Academy of Medicine has identified priorities central to helping the nation achieve better health at lower cost.

Context: Fundamental Challenges

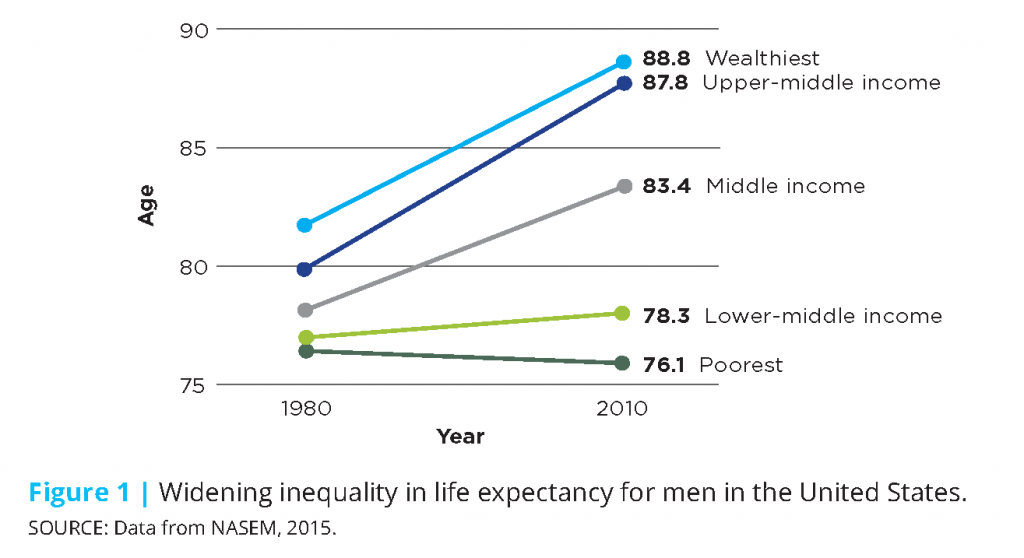

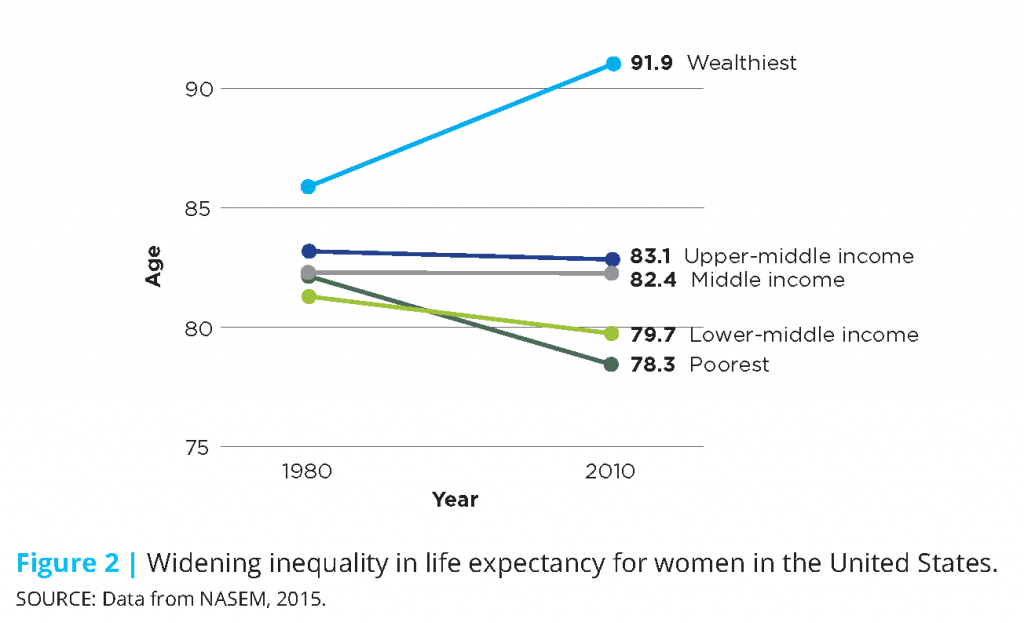

Health care today is marked by structural inefficiencies, unprecedented costs, and fragmented care delivery, all of which place increasing pressure and burden on individuals and families, providers, businesses, and entire communities. The consequent health shortfalls are experienced across the whole population, but disproportionately impact our most vulnerable citizens due to their complex health and social circumstances. This is evidenced by the growing income-related gap in life expectancy for both men and women (see Figures 1 and 2). Today, higher-income men can expect to live longer than they did 20 years ago, while life expectancy for low-income males has not changed. Higher-income women are also anticipated to live longer, but life expectancy for low-income women is projected to decline.

Beyond systemic and structural issues, this country is faced with serious public health challenges and threats: emerging infectious diseases; an evolving opioid epidemic; alarming rates of tobacco use, obesity, and related chronic diseases; and a rapidly aging population that requires great support from our health care delivery and financing systems. Following are summarized fundamental challenges with which our health and health care system must be better prepared to contend.

Persistent Inequities in Health

In spite of the United States’ great investment in health care services and the state-of-the-art health care technology available, inequities in health care access and status persist across the population and are more widespread than in peer nations (Lasser et al., 2006; Avendano, 2009; van Hedel et al., 2014; Siddiqi et al., 2015). Over the past 15 years, individuals in the upper income brackets have seen gains in life expectancy, while those in the lowest income brackets have seen modest to no gains (Chetty et al., 2016). And while health inequities are seen most acutely across socioeconomic and racial/ethnic lines, they also emerge when comparing other characteristics such as age, life stage, gender, geography, and sexual orientation (Braveman et al., 2010; Artiga, 2016). However, health status is not predetermined; rather, is the result of the interplay for individuals and populations of genetics, social circumstances, physical environments, behavioral patterns, and health care access (McGinnis et al., 2002). Similarly, inequities in health are not inevitable (Adler et al., 2016; McGinnis et al. 2016); efforts to lessen social disadvantage, prevent destructive health behaviors, and improve built environments could have important health benefits.

Rapidly Aging Population

By 2060, the number of older persons (ages 65 years or older) is expected to rise to 98 million, more than double the 46 million today; in total population terms, the percentage of older adults will rise from 15% to nearly 24 (Mather et al., 2015; ACL, 2016). This trend is explained by the fact that people are living longer and the baby boomers are entering old age. The aging population is placing increasing demand on our health care delivery, financing, and workforce systems, including informal and family caregivers. As more and more people age, rates of physical and cognitive disability, chronic disease, and comorbidities are anticipated to rise, increasing the complexity and cost of delivering or receiving care. In particular, Medicare enrollments and related spending will rise, as will Medicaid and out-of-pocket spending for long-term care services not provided under Medicare (CMS 2016a; ACL, 2016). Ensuring that the elderly can be adequately cared for and supported will require greater understanding of their social, medical, and long-term needs, as well as workforce skills and care delivery models that can provide complex care (Rowe et al., 2016).

New and Emerging Health Threats

U.S. public health and preparedness has been strained by a number of recent high profile challenges, such as lead-contaminated drinking water in several of our cities; antibiotic resistance; mosquito-borne illnesses such as Zika, Dengue, and Chikungunya; diseases of animal origin, including HIV, influenzas, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), Middle East Respiratory Syndrome-Coronavirus (MERS-CoV), and Ebola; and devastating natural disasters, such as hurricanes Sandy and Katrina (Morens and Fauci, 2013). The emergence of these threats, and in some cases the related responses, highlights the need for the public health system to better equip communities to better identify and respond to these threats.

Persisting Care Fragmentation and Discontinuity

While recent efforts on payment reform have aimed to advance coordinated care models, much of health care delivery still remains fragmented and siloed. This is particularly true for complex, high-cost patients—those with fundamentally complex medical, behavioral, and social needs. Complex care patients include the frail elderly, those who are disabled and under 65 years old, those with advanced illness, and people that have multiple chronic conditions (Blumenthal et al, 2016). High-need, high-cost patients comprise about 5% of the patient population, but drive roughly 50% of health care spending (Cohen and Yu, 2012). Individuals with chronic illness and/or behavioral health conditions often experience uncoordinated care which has been shown to result in lower quality care, poorer health outcomes, and higher health care costs (Druss and Walker, 2011; Frandsen et al., 2015).

Health Expenditure Costs and Waste

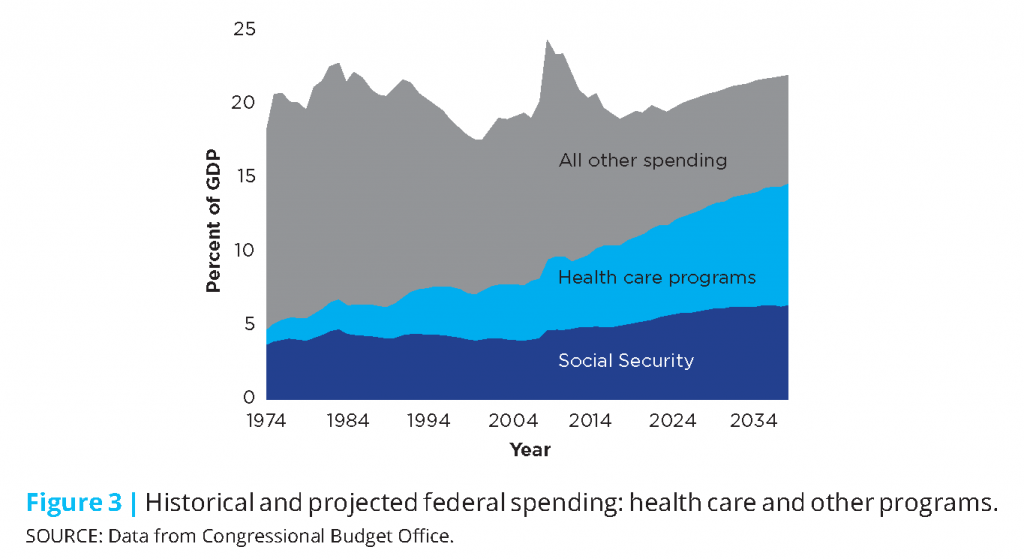

It is widely acknowledged that the U.S. is experiencing unsustainable cost growth in health care: spending is higher, coverage costs are higher, and the costs associated with gaining access to the best treatments and medical technologies are similarly increasing. In 2015, health care spending grew 5.8%, totaling $3.2 trillion or close to 18% of GDP. Of that, it has been estimated that approximately 30% can be attributed wasteful or excess costs, including costs associated with unnecessary services, inefficiently delivered services, excess administrative costs, prices that are too high, missed prevention opportunities, and fraud (IOM 2010; IOM 2013). Resources consumed in this way represent significant opportunity costs both in terms of higher-value care that could be pursued, and in terms of the social, behavioral, and other essential services necessary for effective care and good outcomes. Figure 3 shows how rising federal spending on health care programs, as a percentage of GDP, is outpacing and compressing other parts of the federal budget.

Constrained Innovation Due to Outmoded Approaches

The U.S. has long been a global leader in biomedical innovation, but our edge is increasingly at risk due to outdated regulatory, education and training models. In the drug and medical device review and approval process, uncertainty and unpredictability around approval expectations adds complication, delay, and expense to the research and development process, and can translate to a disincentive to investors (Battelle, 2010). Simultaneously, there are concerns that the movement toward population-based payment models may stifle innovation and patient access by placing excessive burden on manufacturers to demonstrate the value of their products upfront in approval and reimbursement decisions. Further, our biomedical education and scientific training pathways are outdated and fragmented (Kruse, 2013; Zerhouni et al., 2016). Talented young scientists are increasingly discouraged from pursuing careers in biomedical research due to rising educational requirements and tuition costs combined with uncertain career pathways.

Context: Realistic Tools

The good news is that the nation is equipped to tackle these formidable challenges from a position of unprecedented knowledge and substantial capacity. Locally and nationally, new models of care delivery and payment are emerging that seek to reduce waste by rewarding value over volume, are more patient-centric, and are driving better care coordination and integration. The rise of digital health technology has opened the door to enhanced health care and provider access, greater patient engagement, as well as data and tools to support more personalized and tailored health care. Further, increased recognition of the importance of community and population health strategies has helped foster a greater system-wide focus on prevention and overall health promotion opportunities. And, thanks to major advancements and continued innovation in biomedicine and technology, diagnostic capabilities and treatments have expanded greatly, allowing Americans to live longer, more productive lives. Following are several of the crosscutting opportunities for progress identified over the course of the initiative and its work.

A New Paradigm of Health Care Delivery and Financing

Against the backdrop of fee-for-service payment models that can incentivize unnecessary or duplicative care, progress is underway toward a more value-based, person-centric approach. This transformation represents a common effort stemming from the initiative from many quarters—health care leaders, providers, policymakers, and academic experts—responding to rising health care costs, deficiencies in care quality, and inefficient spending. Under fee-for-service, health care services are paid for by individual units, incentivizing providers to order more tests and administer more procedures, sometimes irrespective of need or expected benefit to the patient. In contrast, value-based, alternative payment models (APMs) incentivize providers to maintain or improve the health of their patients, while reducing excess costs by delivering coordinated, cost-effective, and evidence-based care.

Fully Embracing the Centrality of Population and Community Health

With the increasing emphasis on value-based care, and with increasing recognition that factors outside of health care are among the strongest determinants of the health and health care needs of individuals and population segments, efforts are growing to strengthen the activities, tools, and impact related to and community health in U.S. health care today (Kindig and Stoddart, 2003). It is increasingly acknowledged that effective measures to improve health status and health outcomes over groups and over time require tending to the conditions and factors that affect individual and population health over the life course, including social, behavioral, and environmental determinants. While health care in the United States has developed on a track substantially apart from, and generally uncoordinated with, programs directed to the other determinants (Goldman et al., 2016), great gains stand to be achieved if they are more effectively integrated into care delivery and planning.

Increased Focus on Individual and Family Engagement

While calls to more effectively and meaningfully engage patients and their families in care design and decisions are not new, the awareness of the importance to clinical outcomes has increased substantially, as have the tools to facilitate that engagement (Topol, 2015). Today, there is increased focus on expanding the roles of individuals and families in not only designing and executing health care regimens, but in measuring progress, and in developing and testing new and innovative treatments. Across the care continuum, there is greater recognition that patients and families—as the end-users of the services provided—are an integral part of the decision process, whose engagement, understanding, and support is imperative to individual health and well-being, as well as system efficiency, quality, and overall performance.

Biomedical Innovation, Precision Medicine, and New Diagnostic Capabilities

Biomedical science and innovation has accelerated at a tremendous pace, and, with increasing knowledge, available treatments and technologies to combat illness and disease, Americans are able to live longer, healthier lives. Since the 1980s, nearly 300 novel human therapeutics have been approved covering more than 200 indications (Evens and Kaitin, 2015). Breakthroughs in biotechnology have generated new treatments and cures for diseases that were previously untreatable or could only be symptomatically managed, such as cardiovascular disease, HIV, and Hepatitis C. Diagnostics have also become more sophisticated and precise, as diagnostic capabilities have expanded. Today, the field of precision medicine is emerging and has the potential to transform medicine by tailoring diagnostics, therapeutics, and prevention measures to individual patients (Dzau et al., 2016). Precision medicine has great promise to improve care quality by delivering more accurate and targeted treatments, and increase care efficiency by reducing the use of multiple and/or ineffective tests and therapies.

Advances in Digital Technology and Telemedicine

The ability exists to build a continuously learning health system (IOM, 2007; 2013). Health and health care are being fundamentally transformed by the development of digital technology with the potential to deliver information, link care processes, generate new evidence, and monitor health progress (Perlin et al., 2016). Health information technology includes electronic health records (EHRs), personal health records, e-prescribing, and m-health (mobile health) tools, including personal health tools, such as personal wellness devices and smartphone apps, and online peer support communities (ONC, 2013). All of these technologies are changing the way the health system operates, how individuals interact with the health system and one another, and the data available to monitor and improve health and make care decisions. Technological advances in the health arena have also enabled the rise of telemedicine, which allows patients and clinicians to interact with one another remotely.

Promise of “Big Data” to Drive Scientific Progress

Rapid advancement in cost-effective sensing and the expansion of data-collecting devices have enabled massive datasets to be continuously produced, assembled, and stored. The amount of high-dimensional data available is unprecedented and will only continue to grow. If effectively harnessed and curated, big data could enable science to “extend beyond its reach” and allow technology to become more “adaptive, personalized, and robust (NRC, 2013).” In particular, these largescale data stores have the potential to reveal and further our understanding of subtle population patterns, heterogeneities and commonalities that are inaccessible in smaller data (Fan et al., 2014). Using big data, we can learn more about disease causes and outcomes, advance precision medicine by creating more precise drug targets, and better predict and prevent disease occurrence or onset (Khoury and Ioannidis, 2014).

****

(Please click here if you would like to access the full paper, including references.)

Read excerpts from from McClellan et al. (2017), “Payment reform for better value and medical innovation”

- McClellan, M. B., D. T. Feinberg, P. B. Bach, P. Chew, P. Conway, N. Leschly, G. Marchand, M. A. Mussallem, and D. Teeter. 2017. Payment Reform for Better Value and Medical Innovation. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.31478/201703d

Introduction

Over the past 50-60 years, biomedical science and technology in the United States have advanced at a remarkable pace, allowing Americans to live longer, healthier lives. And while we have gained tremendous benefit from continuous medical innovation, health care delivery has simultaneously become more complex, expensive, and, in some ways, less patient-centric (IOM, 2001). In 2015, US health care spending grew 5.8%, totaling $3.2 trillion or close to 18% of GDP (CMS, 2016a), and it has been estimated that upwards of 30% of health expenditures may not contribute to health improvement (IOM, 2013). In tandem, health indicators and outcomes in the US are lagging, including measures of access, efficiency, equity, and quality (IOM and NRC, 2013). And while these trends could be attributed to myriad factors, ultimately, how we pay for care strongly influences how care is delivered (IOM, 2013). With fee-for-service (FFS)—the longstanding, traditional payment model used in the U.S.—health care services are paid for individually and aggregate payment is driven by the volume of services rendered. In an effort to reign in health care costs, increase clinical efficiency, encourage greater coordination among providers to better meet the needs of patients, and provide value for true engagement of patients’ and family members’ care decisions, payment reform efforts are focusing on value-based models of care delivery. These models aim to incentivize providers to keep their patients healthy, and to treat those with acute or chronic conditions with cost-effective, evidence-based treatments.

Value-based payment strives to promote the best care at the lowest cost, allowing patients to receive higher-value, higher quality care. Payment reform, with the goals of shifting provider payments and incentives from volume to value, is a health policy issue that has bipartisan support. Consistent with these goals and building on early, successful payment reform models carried out in the public and private sectors (Abrams et al., 2015), provisions contained in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA) set in motion several initiatives that seek to reform how health care is paid for and delivered more broadly. Through these provisions, the law uses a multi-pronged approach to instituting reforms, focusing on: testing new payment and care delivery models that aim to increase care coordination, quality, and efficiency (e.g. patient-centered medical homes and accountable care organizations); shifting the provider reimbursement system orientation to outcomes rather than services; and investing in methods to improve health system efficiency, such as issuing grants to establish community health teams to support a medical home model (Abrams et al., 2015; Davis et al., 2010).

Payment and delivery reform, alongside related legislative and regulatory changes, has the potential to make transformative models of health care delivery more sustainable, with the promise of better outcomes, lower costs, and more support for investment in new treatments that are truly valuable. Simultaneously, the potential for medical innovations to improve the patient care experience, produce better health outcomes, and reduce health cost seems greater than ever. This includes new treatments for unmet needs, new cures, innovations in digital health, much larger data analytics, and team-based care that is much more prevention-oriented, convenient and personalized. As with most transformative change, transitioning to value-based models of care delivery and payment has been met with some challenges. While payment reforms have shown some promising results, overall impacts on spending trends have been modest and critical obstacles remain to successful implementation, including inadequate performance measures, regulatory barriers, insufficient evidence on successful models, and limited knowledge of the competencies required for providers to succeed within this new paradigm. Policymakers will need to address and mitigate these and other challenges as they chart the next steps of payment reform. This discussion paper seeks to highlight payment reform initiatives underway, underscore pressing challenges in need of attention, and provide recommended vital directions to advance reform and better ensure its success.

Payment Reform Initiatives and Stakeholder Contributions

The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation’s Pilot Initiatives

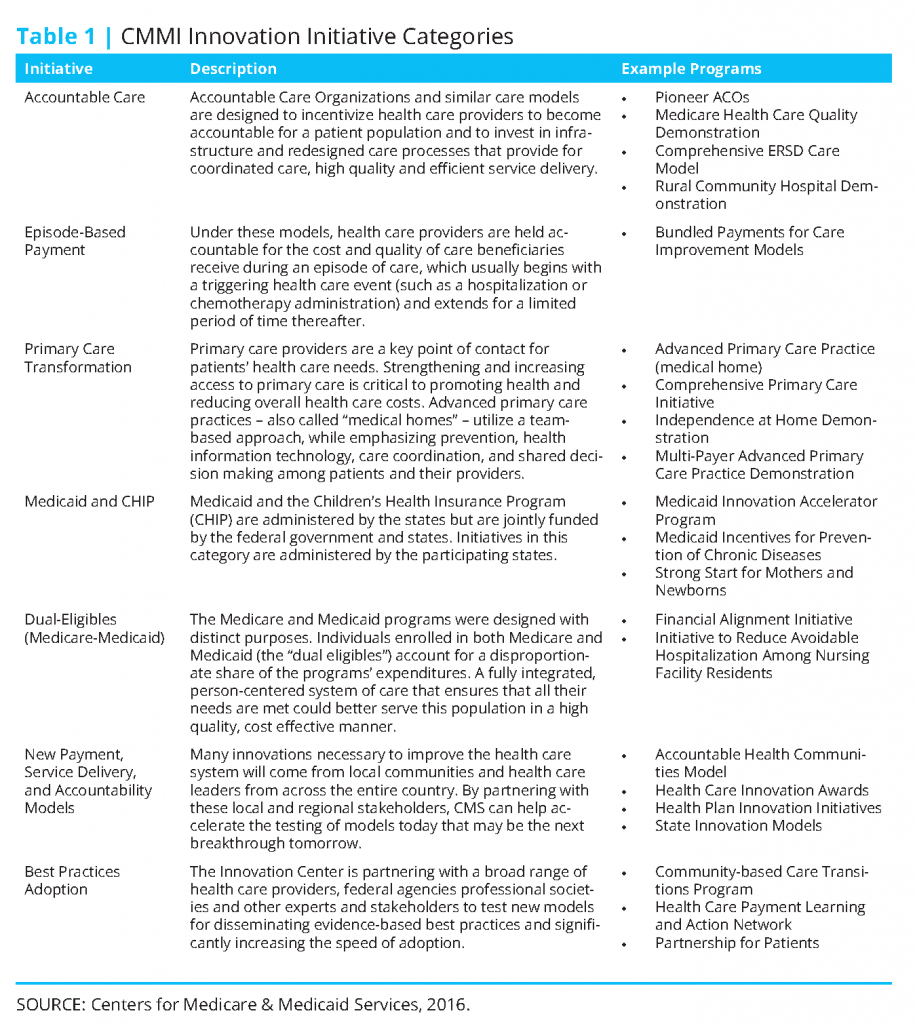

Among the most significant of the payment reform provisions contained in the ACA is the creation of the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI or “Innovation Center”) within the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), which went into effect in 2011. The Innovation Center was established to identify, develop, assess, support, and spread new payment and delivery models that hold significant promise for lowering expenditures under Medicare, Medicaid, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), while simultaneously improving or maintaining quality of care delivered (Berenson and Cafarella, 2012; Abrams et al., 2015). The law authorizes the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) to spread successful CMMIsupported payment innovations, if sufficient evidence exists demonstrating reduced costs and improved outcomes (Guterman et al., 2010). The law appropriates $10 billion to the Innovation Center every ten years; CMMI received the first $10 billion for 2011-2019 to execute pilot programs initiated during this time. The law identified several priorities and existing models that CMMI ought to consider in constructing its pilots, emphasizing reforms to promote care coordination, encourage efficient and high-quality care, and improve patient safety. The Innovation Center organizes its innovation models into seven categories (Table 1). Currently, CMMI has 33 ongoing pilot initiatives across these categories, and another 25 initiatives under development, announced, or just getting started (CMS, 2016b).

Patient-centered medical homes (medical homes), accountable care organizations (ACOs), and bundled payments are among the most commonly cited and discussed alternative payment models. A medical home is a model that provides care that is comprehensive, patient-centered, coordinated and team-based, accessible, quality and safe (AHRQ, 2016). Medical home models rely heavily on a primary care practice to deliver and coordinate the majority of care for the beneficiary. An accountable care organization is a group of health care providers, such as doctors, hospitals, health plans, who voluntarily come together to provide coordinated, high-quality care to populations of patients, and agree to assume responsibility for the quality and costs of care provided. To encourage the formation of ACOs, the ACA established the Medicare Shared Savings Program, whereby participating ACOs could keep half of the resulting savings if they met the quality benchmarks established and kept costs below budget. ACOs could also enter into a “two-sided risk” model—with potential shared savings of up to 60%, if total savings exceed the minimum savings rate—which would require the ACO to pay for a portion of the losses if spending were to go beyond the established budget. While participation in the Shared Savings Program exceeded expectations, overall performance results have been mixed (Abrams et al., 2015). Finally, a bundled payment reimburses the provider(s) in a single payment for all the services required to treat a specific condition or provide a specific treatment over a defined period of time. Bundled payments incentivize providers to come in below budget for a given care episode.

HHS’ Historic Shift to Alternative Payment Models

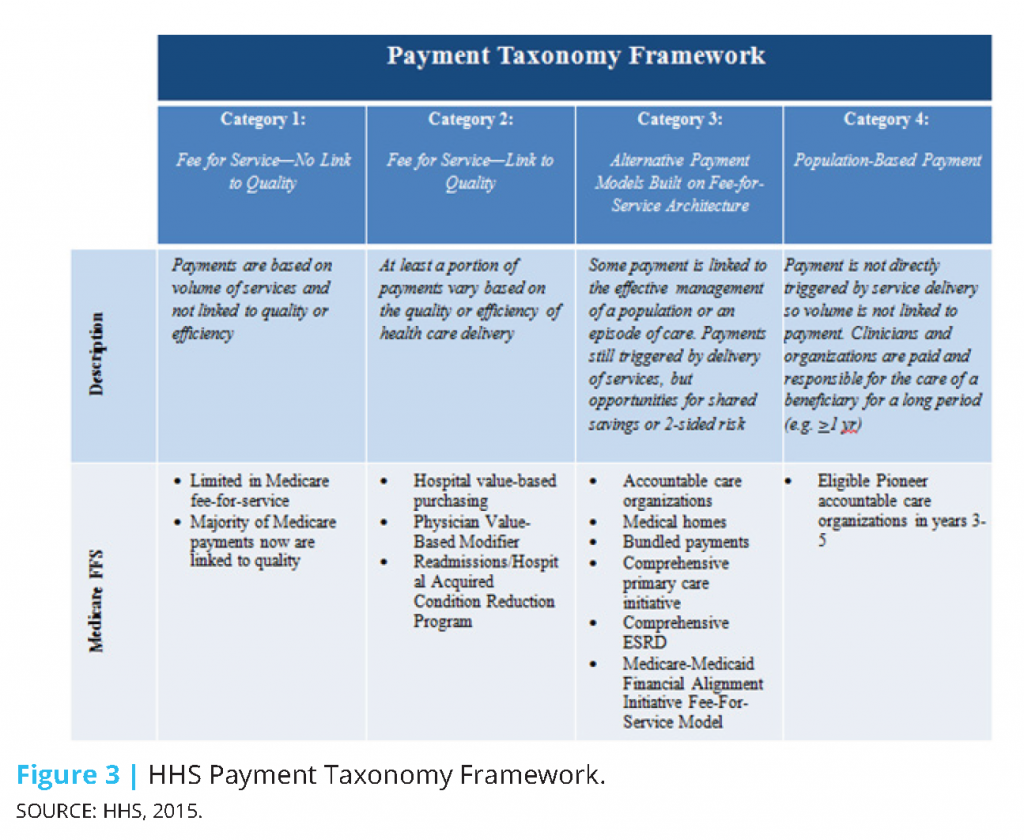

In January 2015, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) made a historic announcement, setting a timeline with specific, measurable goals to shift Medicare and the greater health care system toward reimbursing providers through alternative payment models (APMs) (HHS, 2015). In setting its goals, HHS adopted a framework categorizing health care payment models based on how providers receive payment for the care they provide (CMS, 2015):

- Category 1: Fee-for-service with no link of payment to quality

- Category 2: Fee-for-service with a link of payment to quality

- Category 3: Alternative payment models built on fee-for-service architecture

- Category 4: Population-based payment

Value-based payments are considered those falling within categories 2-4. Based on the framework, moving from category 1 to category 4 would necessitate both increased accountability for quality and total cost of care, and shifting focus toward population health management.

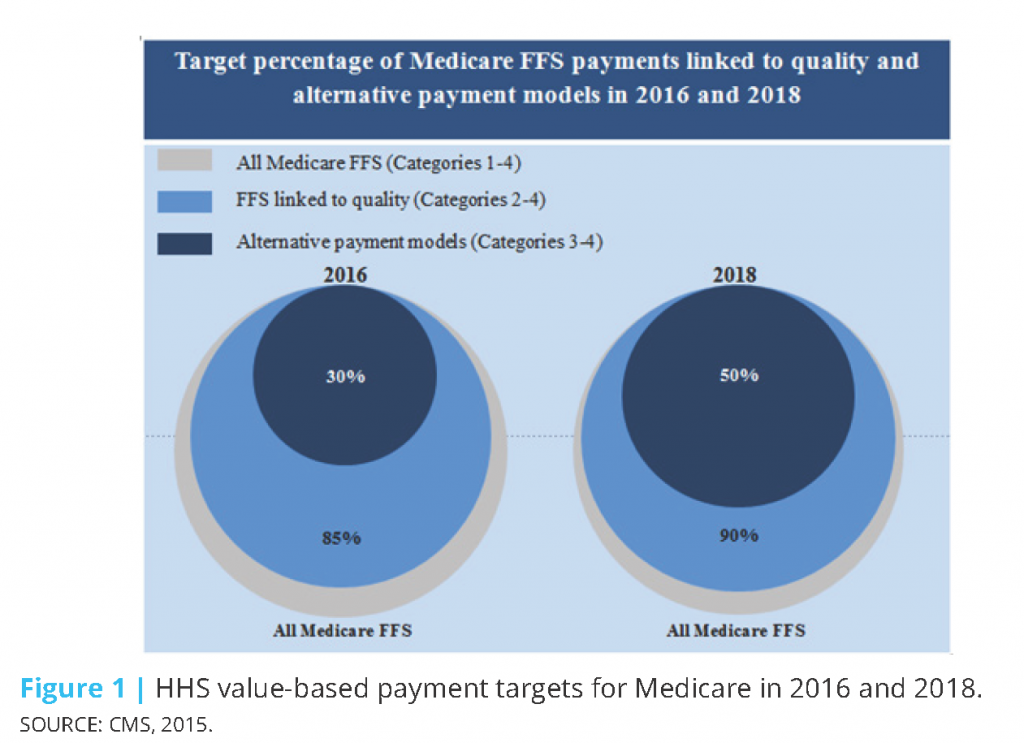

In 2015, HHS set the goal of tying 30% of traditional (fee-for-service) Medicare payments to APMs (categories 3 and 4) by the end of 2016, and tying 50% of payments to APMs by the end of 2018 (CMS, 2015). HHS also set goals of tying 85% of all traditional Medicare payments to quality or value (categories 2-4) by 2016 and 90% by 2018 through programs such as the Hospital Value Based Purchasing and Hospital Readmissions Reduction Programs (Figure 1). In 2011, while over half of Medicare payments were linked to quality, practically none were in alternative payment models. By March 2016, almost a year ahead of schedule, the 2016 goals were met with 30% of Medicare payments tied to alternative payment models and 85% tied to quality. CMS continues to move toward meeting its 2018 goals.

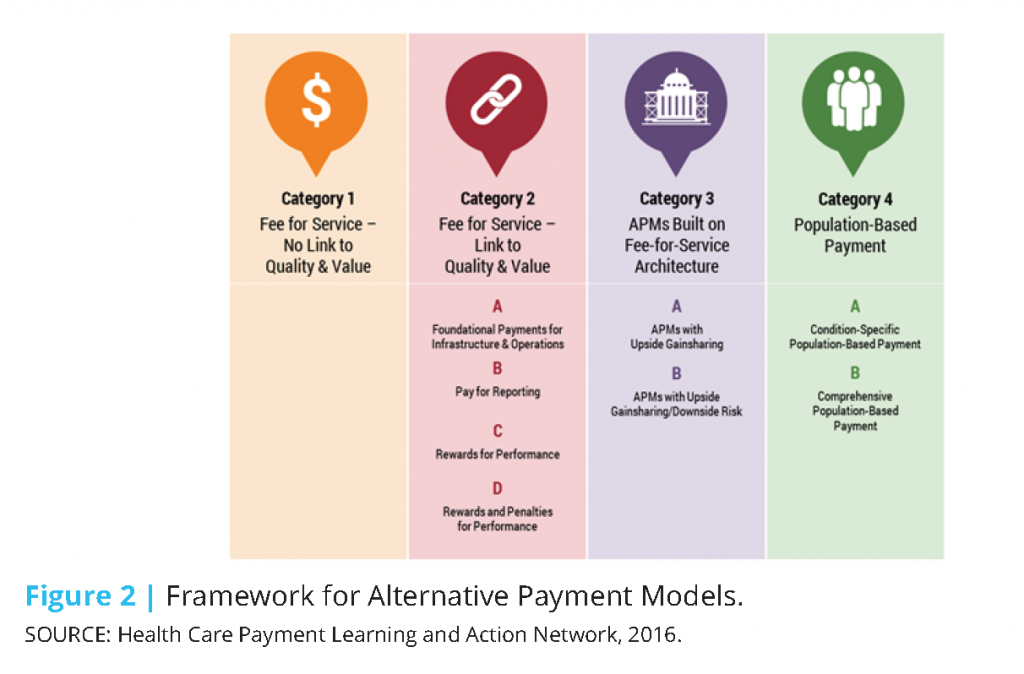

To facilitate the scale and spread of these goals beyond Medicare, HHS created the Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network (LAN) to align stakeholders across sectors and accelerate the transition to value-based payment. Through the LAN, HHS works with private payers, employers, consumers, providers, states and state Medicaid programs, and other partners to adopt and expand APMs into their programs. Consistent with the goals set for Medicare, the LAN seeks to facilitate tying 30% of payments to APMs by 2016 and 50% by 2018 across the health care system. As part of their efforts, the LAN convened a work group to build on HHS’ framework for categorizing and measuring APMs. The framework developed (Figure 2) expands upon that originally developed by HHS (Figure 3) and includes 4 primary categories and 8 subcategories. The framework rests on seven principles identified by the workgroup (HCPLAN, 2016):

- Patients must be empowered as partners in health care transformation; changing providers’ financial incentives is not sufficient to achieve person-centered care.

- Health care spending must shift significantly towards population-based, more person-focused payments.

- Value-based incentives should ideally reach the providers that deliver care.

- Payment models that do not take quality into account are not considered APMs in the APM Framework, and do not count as progress toward payment reform.

- Value-based incentives should be intense enough to motivate providers to invest in and adopt new approaches to care delivery.

- APMs will be classified according to the dominant form of payment when more than one type of payment is used.

- Centers of excellence, accountable care organizations, and patient-centered medical homes are examples of delivery systems, rather than categories, in the APM Framework.

Alongside the efforts of the LAN, many private organizations and industry consortia have set specific goals to transition to new payment models. The Health Care Transformation Task Force is an example of an industry consortium seeking to align and convene stakeholders across the private and public sectors to accelerate the adoption of value-based care. The Task Force brings together patient, payer, provider, and purchaser groups to collaborate and work together to make system transformation possible. Payer and provider members in the Task Force commit to have 75% of their businesses utilizing value-based payment arrangements by January 2020. Purchaser and patient members commit to building and maintaining the necessary demand, support, and education of their communities to achieve this target (HCTTF, 2016).

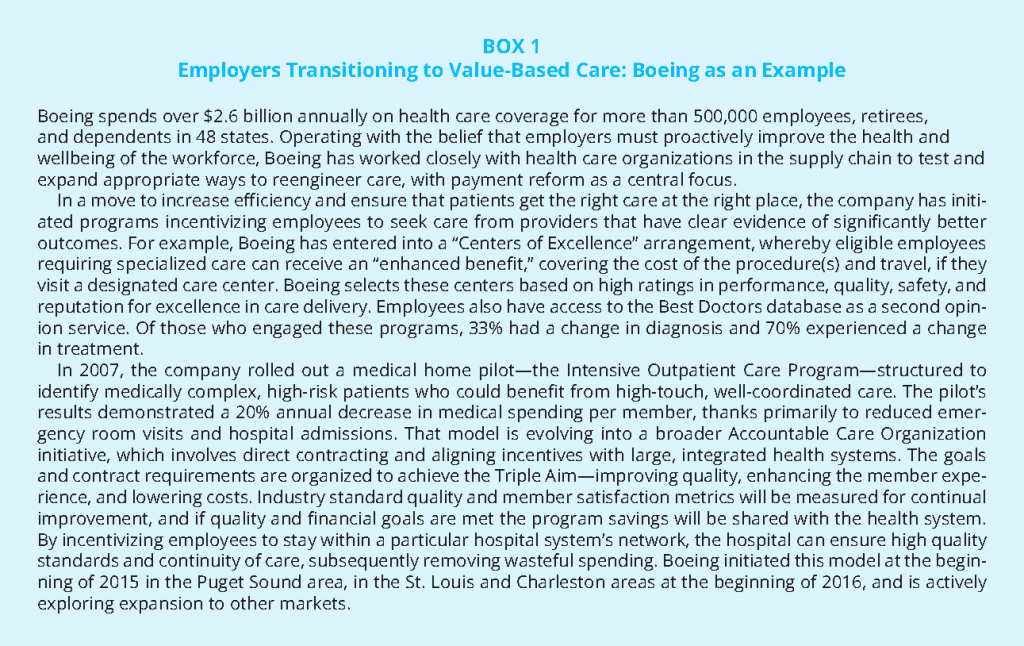

Employer-Led Initiatives and Innovations

Nearly half of people with health insurance in the US receive their coverage through an employer (KFF, 2015). As the costs of health care have risen, so too have the financial burdens on the employers providing coverage. While some employers have responded by reducing or eliminating coverage, others have increased their involvement in efforts and initiatives that seek to curb costs and improve care quality (Schilling, 2011). Although employers have long been involved in efforts and initiatives to improve health care quality, overall, most payment reform efforts have not been spearheaded by employers (AcademyHealth et al., 2013). Many small to mid-size organizations often lack the needed number of employees and/or critical competencies to drive these initiatives. Larger employers, however, with the sophistication and resources to influence change, have been capable of driving advancement in this space, often in partnership with providers. The payment reform experience of Boeing illustrates these trends (Box 1). Boeing has worked closely with health care organizations to test and expand appropriate ways to reengineer care, with payment reform as a central focus. To increase efficiency and ensure that patients get the right care at the right place, the company has initiated programs incentivizing employees to seek care from providers that have clear evidence of significantly better outcomes, and has aligned with providers committed to improving quality, enhancing the member experience, and lowering costs.

Traditionally, by participating in self-funded plans, large employers have assumed most of the insurance risk and thus cost of care for how the system performs, but have had very little control over how health care is delivered. In recent years, however, employers have been “doubling down on opportunities to impact health care quality and costs at the source – by working more closely with high performing providers through select networks and providing better information to help employees make higher-value health care choices” (Hoo and Lansky, 2016). In a 2014 Aon Hewitt Health Care survey of over 1200 medium to large employers, 65% of companies identified moving toward provider payment models that strive for “cost-effective, high-quality” outcomes as a key strategic direction going forward (Aon Hewitt, 2014). Employers are hopeful that as financial risk becomes shifted to providers, increased innovation and competition will ultimately lead to overall reduced costs and better health outcomes for beneficiaries. And, when risk is shared jointly among groups of providers, providers will be more likely to deliver coordinated, integrated care.

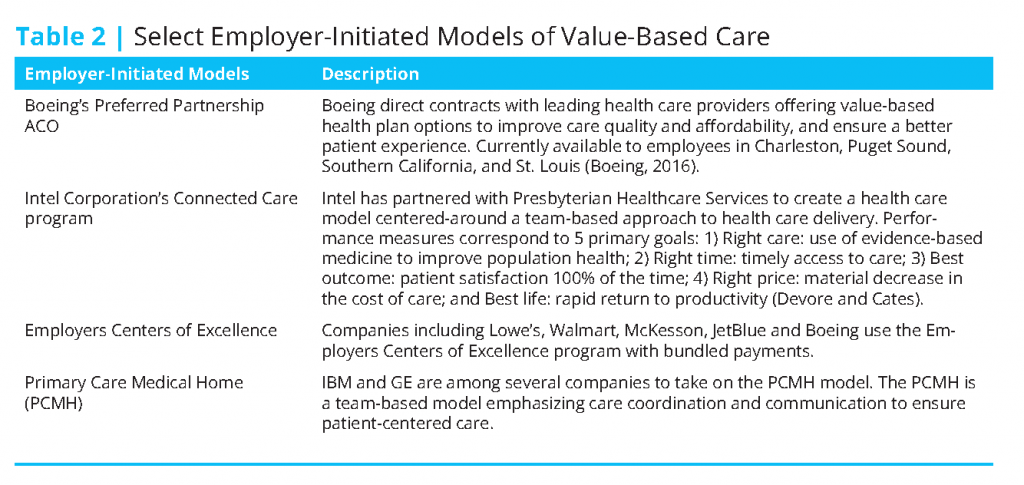

As the system transitions, employers are increasingly participating in and/or developing innovative, value-based approaches to delivering patient-centered, lower-cost, quality health care. In fact, more and more, employers are partnering with providers to build high-performance networks of their own through ACOs, medical homes, and centers of excellence (Table 2) (Hoo and Lansky, 2016).

Insurer-Led Initiatives and Innovations

As the health care system transitions from a fee-for-service to value-based approach, insurers are playing an important role in advancing innovative alternative payment models and approaches. For example, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts’ (BCBSMA) payment reform initiative, the Alternative Quality Contract (AQC) has been recognized for developing new and effective partnerships with its members and providers. The AQC seeks to reduce costs while improving quality and health outcomes by using both payment incentives as well as provider support tools. The model rests on a few core elements: a global budget structure; a significant performance incentive system; long-term contract assurance (3-5 years) between BCBSMA and providers with fixed spending and quality targets; and clinical and information support, including group-specific reporting and analysis on spending and quality performance, as well as educational and best-practice sharing forums (Seidman et al., 2015). The AQC has a quality measurement system that includes 64 measures (such as clinical performance and outcomes, patient experience), each of which has a range of “performance gates” to score and reward quality care. This performance score is not only tied to provider payment, but also to the provider’s share of budget surplus and/or deficit. For example, with a higher quality score, a provider will get to keep more of the budget surplus and have to pay less of the deficit owed. Overall, the AQC model has been shown to be effective at improving health outcomes and quality, while reducing costs (Seidman et al., 2015; McKesson, 2016). AQC’s success has been attributed to a combination of its robust incentives structure, as well as commitment to transparent sharing of data and best practices with its providers.

BCBSMA’s AQC is a good case example of the ways in which payers are advancing payment reform models and initiatives. It offers several best practices for insurers to drive and/or promote successful transformation. In 2015, Avalere examined BCBSMA’s experience with the AQC and identified a series of observations related to the important role payers play in advancing alternative payment models and approaches (Seidman et al., 2015):

- Payment reform programs can significantly change provider behavior: if designed well, models can reduce costs and enable better quality care across providers.

- Changing behavior requires providers to have “skin in the game,” but payers need to meet providers where they are today: effective and meaningful incentive schemes need to be in place to realize the desired behavior.

- New payment models should hold providers accountable for the full range of patient care costs: full accountability promotes care coordination, efficiency, and controlled spending.

- Providers can implement meaningful change, but need time, consistent goals, and a similar commitment from payers to do so: provider transformation requires time, support, and commitment from payers.

- Providers need detailed spending and quality information and clinical support to take on risk: transparency and access to data and care redesign support from payers are critical as providers assume more financial risk.

- Payers with significant local presence are best positioned to implement innovative payment models: payers with greater market share are more apt to have the resources and ability to achieve provider buy-in.

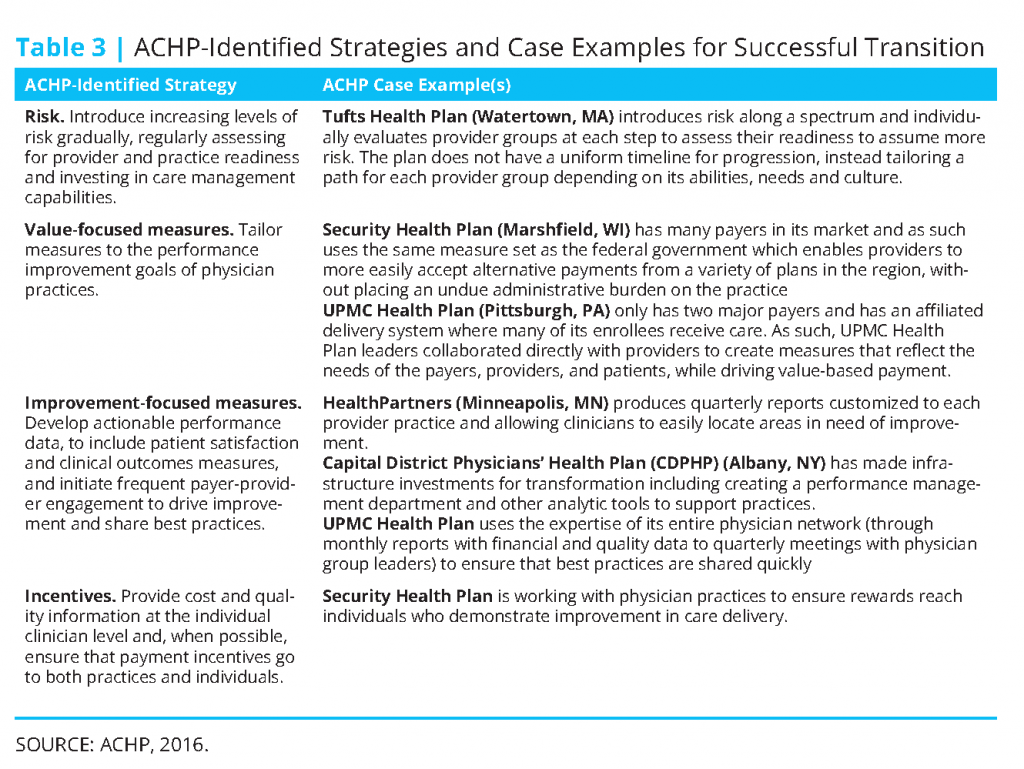

Much like the observations identified by Avalere, the Alliance of Community Health Plans (ACHP) has identified a series of strategies, best practices, and related case examples for ensuring the success of innovative payment and delivery models (ACHP, 2016) (see Table 3). A few of the case examples noted are provider-sponsored plans, which have been growing in number as physician groups, health systems, and hospitals seek to reduce costs, improve care quality, and better meet the needs of the communities they serve.

Engaging Patients in Delivery and Payment Reform Initiatives

Methods to most effectively engage consumers in payment reform discussions are still evolving—partially due to the fact that the intricacies of payment reform can be largely foreign to the average health care consumer. Notably, the direct effect of alternative payment models on patients can be said to be variable (Delbanco, 2015). In the context of pay for performance, patients may not notice any discernable difference in their care. In ACO or medical home settings, however, there may in fact be a noticeable difference in the patient’s care experience (Delbanco, 2015). In fact, research has been conducted indicating that, in these settings, patients recognized improvements in their care coordination and were overall more satisfied with their care (Miller, 2014). In focus group research conducted by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, focus group participants indicated that consumers (generally speaking) were not that interested in learning about the provider reimbursement process, and were uncomfortable with the idea that payment is linked to their health and health care (AF4Q, 2011). Participants indicated that consumers do want enhanced quality from the health care system, including better primary care and coordination. Depending on the payment reform model, patients may desire and have use for varying levels of information.

Engaging consumers and consumer advocates in advancing payment reform innovations is important to driving progress. Involving consumers, caregivers and their advocates in the process better assures that new models or approaches will actually have the intended effects of bettering the patient experience, improving outcomes, safety and quality, and controlling costs. Several hospitals and health systems, including the MCG Health System in Georgia and the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Massachusetts, have made deliberate efforts to deliver care in this way since the mid-1990s (AHA, 2005).

Today, continued efforts are underway to better engage consumers and their advocates in the design and delivery of care to best meet their needs. The activities of several organizations are developing efforts to help consumer advocates address health care and cost issues, such as the Healthcare Value Hub, created by Consumers Union. And, in an effort to engage patients and their families directly, Patient and Family Advisory Councils offer a model of engagement that has been used in delivery and payment reform discussions. These councils serve as an advisory resource, bringing together patients, their families, and members of the health care team to improve the experience of the patient and their family. The role of the council is to promote improved relationships, provide a venue for information sharing, and facilitate communication and coordination between patients, families, and the care team, all of which serves to actively involve patients and their families in the care design and delivery process (IPFCC, 2002). RWJF Aligning Forces for Quality communities in Humboldt County, CA, Maine, and Oregon employed and had successes with these advisory councils during payment reform discussions (AF4Q, 2014).

****

(If you would like to access the entire article, including references, please click here.)