Chapter 1 – Who Are You?

1.2 Identifying Goals

There has been considerable attention given to the importance of college students identifying their educational objectives and majors as soon as possible. Some high schools are working with students to identify these goals earlier. Goal identification is a way to keep track of what we would like to accomplish, as well as a mechanism to measure our success in achieving these goals. This section will focus on examining academic goals and discovering better and more structured approaches to developing goals.

How To Start Reaching Your Goals

Without goals, we aren’t sure what we are trying to accomplish, and there is little way of knowing if we are accomplishing anything. If you already have a goal-setting plan that works well for you, keep it. If you don’t have goals or have difficulty working towards them, try this.

Make a list of all the things you want to accomplish for the next day. Here is a sample to-do list:

- Go to the grocery store

- Go to class

- Pay bills

- Exercise

- Social media

- Study

- Eat lunch with a friend

- Work

- Watch TV

- Text friends

Your list may be similar to this one, or it may be completely different. It is yours, so you can make it however you want. Do not be concerned about the length of your list or the number of items on it. You now have the framework for what you want to accomplish the next day. Hang on to that list. We will use it again.

Now, take a look at the upcoming week, the next month, and the next year. Make a list of what you would like to accomplish in each of those time frames. If you want to go jet skiing, travel to Europe, or get a bachelor’s degree, write it down. Pay attention to detail. The more detail within your goals, the better. Ask yourself, what is necessary to complete your goals?

With those lists completed, take into consideration how the best goals are created. Commonly called “SMART” goals, it is often helpful to apply criteria to your goals. SMART is an acronym for Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Realistic, and Timely. Are your goals SMART goals? For example, a general goal would be, “Achieve an ‘A’ in my anatomy class.” But a specific goal would say, “I will schedule and study for one hour each day at the library from 2 pm-3 pm for my anatomy class to achieve an ‘A’ and help me gain admission to nursing school.”

Now, revise your lists for the things you want to accomplish in the next week, month, and year by applying the SMART goal techniques. The best goals are usually created over time and through the process of more than one attempt, so spend some time completing this. Do not expect to have “perfect” goals on your first attempt. Also, keep in mind that your goals do not have to be set in stone. They can change. Since your environment and situations will change around you over time, your goals should also change.

Another important aspect of goal setting is accountability. Someone could have great intentions and set up SMART goals for all of the things they want to accomplish. But if they don’t work towards those goals and complete them, they likely won’t be successful. It is easy to see if we are accountable for short-term goals. Take the daily to-do list for example. How many of the things that you set out to accomplish did you accomplish? How many were the most important things on that list? Were you satisfied? Were you successful? Did you learn anything for future planning or time management? Would you do anything differently? The answers to these questions help determine accountability.

Long-term goals are more difficult to create and are more challenging for us to stay accountable. Think of New Year’s Resolutions. Gyms are packed in January. By March, traffic at the gym has slowed. Why? Because it is easier to crash diet and exercise regularly for short periods of time than it is to make long-term lifestyle and habitual changes.

Organizing Goals

Place all of your goals, plans, projects and ideas in one place. Why? It prevents confusion. We often have more than one thing going on at a time and it may be easy to become distracted and lose sight of one or more of our goals if we cannot easily access them. Create a goal notebook, goal poster, or goal computer file—organize it any way you want—just make sure it is organized and that your goals stay in one place.

Break Goals into Small Steps

If you decided today that your goal was to run a marathon and then you went out tomorrow and tried to run one, what would happen? You may be thinking that it would be impossible. To run a marathon you need training, running shoes, support, knowledge, experience, and confidence. Often this cannot be done overnight. Instead of giving up and thinking it’s impossible because the task is too big for which to prepare, it’s important to develop smaller steps or tasks that can be started and worked on immediately. Once all of the small steps are completed, you’ll be on your way to accomplishing your big goals. Your college education is no different. Every assignment, every class session, every test is a small step moving you in the direction of your goal of earning a degree.

Educational Planning

At first glance, creating an educational plan might seem straightforward: identify a program of study, determine the required courses, and follow a clear path to completion. In reality, educational planning is rarely that simple or linear. Setting and achieving academic goals in college often requires regular reflection, reassessment, and adjustment.

An educational plan developed with an advisor can help students map out their goals and explore academic pathways. You may have started this process during orientation or an early advising session. Ideally, your plan serves as a road map to guide your course selection and help you progress efficiently toward your goals. But unlike a map, a good educational plan is dynamic—it evolves with you.

Graphics courtesy of Greg Stoup, Rob Johnstone, and Priyadarshini Chaplot of The RP Group

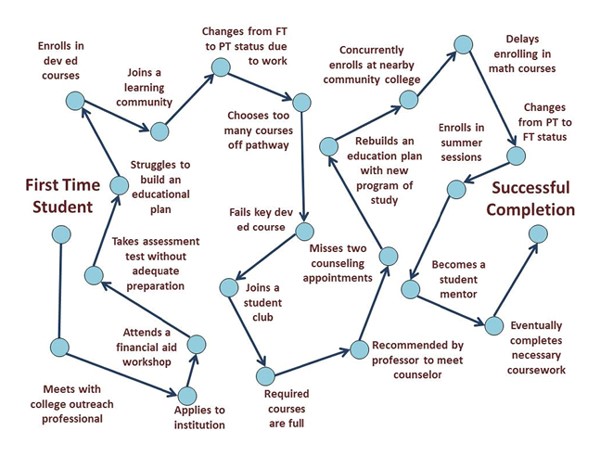

Many students have multiple or shifting goals. You may be interested in double majoring, transferring to a different university, preparing for graduate school, or adding a minor. You may also be discovering your interests and strengths as you go. One student might excel in English while another thrives in math or the arts. These differences can and should influence the order in which courses are taken.

Your personal circumstances also shape your academic path. Some students aim to finish quickly, while others balance full-time jobs or family responsibilities and take fewer units each term. Interests, values, learning styles, GPA requirements, and even referrals to campus support services all play a role in shaping your educational plan.

It’s also completely normal to be uncertain about your major or career direction. While a few students know their future path from a young age, most explore several options before settling on the right one. In fact, around 70% of students change their major at least once, and many do so multiple times. Each shift in direction may require a reassessment of your academic plan.

As a result, what may begin as a neat, linear path often transforms into a winding journey with detours, turns, and revisions. This is not a sign of failure—it’s a natural and expected part of the college experience.

The simple concept and road map often end up looking more like this:

Graphics courtesy of Greg Stoup, Rob Johnstone, and Priyadarshini Chaplot of The RP Group

Because of this complexity, partnering with an academic advisor or counselor is essential. They can help you create, update, and adapt your educational plan as your goals evolve. If you haven’t already, we strongly encourage you to meet with a counselor regularly—ideally once per semester. These sessions are opportunities to express your goals, ask questions, and take an active role in shaping your educational journey.

Citations

- Dillon, Dave. Blueprint for Success in College and Career. OER Commons. https://press.rebus.community/blueprint2/. CC BY 4.0.

- “Advancing Student Success in the California Community Colleges,” California Community Colleges (California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office: Recommendations of the California Community Colleges Student Success Task Force, 2012), https://www.avc.edu/sites/default/files/administration/organizations/basicskills/StudentSuccessResArticles/StudentSuccessTaskForce_Final_Report_1-17-12_Print.pdf

- J. Weissman, C. Bulakowski, and M.K. Jumisko, “Using Research to Evaluate Developmental Education Programs and Policies,” in Implementing Effective Policies for Remedial and Developmental Education: New Directions for Community Colleges, ed. J. M. Ignash (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1997), 100, 73-80.

- Beth Smith et al., “The Role of Counseling Faculty and Delivery of Counseling Services in the California Community Colleges,” (California: The Academic Senate for California Community Colleges).