Chapter 5 – Academic Skills

5.1 Active Reading Strategies

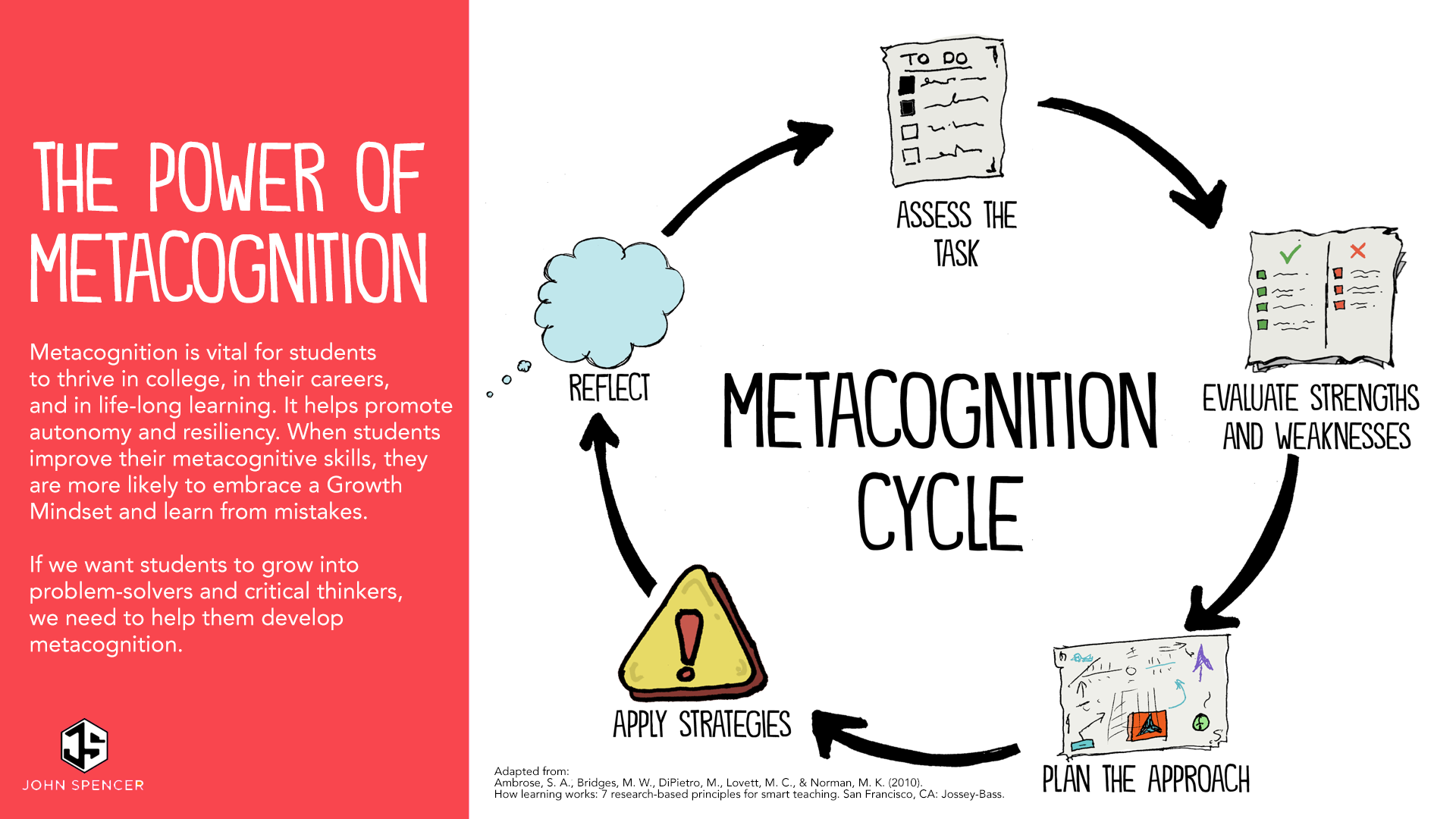

Rarely are students able to simply pick up a textbook, read a chapter from start to finish and retain all of the important information for future lectures and exams. Reading to learn requires you to be active in the process through the metacognitive cycle.

Metacognitive Cycle image courtesy of https://spencereducation.com/metacognition/.

Assess the Task

Prior to diving into a reading, consider what is being asked of you. What type of reading are you engaging in? A textbook, academic journal, case study, or poem? Different types of written work require different reading strategies. Why are you being asked to read this information? Is it background information for a lecture the next day? Are you preparing for a presentation or debate? Will you be tested on the material? Finally, how much reading or how long will the reading take? This will help you develop a study strategy and allocate time appropriately.

Evaluate Strengths and Weaknesses

If you want to be a better swimmer, you practice. If you want to be a better reader, you practice. Read, read, read. Read about history, politics, world leaders, current events, sports, art, music—whatever interests you. Why? Because the more you read, the better a reader you become. And, the more knowledge you will have. Developing a foundation of background knowledge makes learning new knowledge easier. This strategy is focused on making what you are studying important to you and directly relating what you are studying to something in your life. If your attitude is “I will never use this information” and “it’s not important,” chances are good that you will not remember it.

In the book, Content Area Reading: Literacy and Learning Across the Curriculum, Vacca and Vacca postulate that a student’s prior knowledge is “the single most important resource in learning with texts.”2 Reading and learning are processes that work together. Students draw on prior knowledge and experiences to make sense of new information. “Research shows that if learners have advanced knowledge of how the information they’re about to learn is organized — if they see how the parts relate to the whole before they attempt to start learning the specifics — they’re better able to comprehend and retain the material.3

Before reading any material, reflect on what foundational or background knowledge you already know and what gaps in knowledge you have. Also consider your reading skills: quick or slow and steady; are you able to skim and retain or do you need to read each paragraph, stop, and review? These various strengths and weaknesses in knowledge and skill should inform your approach.

Plan the Approach

Before you begin reading, it’s important to plan how you will tackle the material. This metacognitive step involves thinking ahead about your purpose, the structure of the text, and the strategies that will help you understand and retain the information. Ask yourself questions such as: Why am I reading this? What do I need to learn or take away? How much time do I have to devote to it? By setting clear objectives, you can align your reading strategy with your goals—whether you need to scan for key ideas, analyze in detail, or prepare to discuss and apply the material.

One of the biggest challenges students have with reading is accurately assessing how long it will take to read what is assigned. In many cases, it’s important to break the information into chunks rather than to try and read it all at once. One strategy that works well for many students is to break the information up equally per day and adjust accordingly if it takes longer to read than planned. Accurately estimating how much time it will take to complete reading assignments is a skill that takes practice.

Preview the text by looking at headings, subheadings, graphics, and summaries to get a sense of its organization and main points. Decide how you will interact with the material—highlighting, annotating, taking notes, or creating outlines—and schedule breaks to maintain focus. This intentional preparation primes your mind to engage more deeply, reduces the chance of distraction, and ensures your reading time is active rather than passive.

Apply Strategies

Start by reading the introduction and end-of-chapter or section summaries. These will help you understand what the main ideas and goals of the chapter are. Look at what you are reading and how it is connected with other areas of the class. How does it connect with the lecture? How does it connect with the course description? How does it connect with the syllabus or with a specific assignment? What piece of the puzzle are you looking at and how does it fit into the whole picture?

Once you have a sense of a reading’s overall purpose, shift your attention to topic sentences, which reinforce the main idea. Topic sentences are where the author outlines the most important aspects of that paragraph. It probably goes without saying but anything that is bolded or set off from the default print size and style demands your attention. “Sidebars”, such as statistics, brief biographies of authors or persons of note related to the chapter content, charts, graphs, photographs, or illustrations can also hold valuable information. The end of each section or chapter may also contain study questions or glossary terms, which are particularly important tools for self-testing. While they usually appear at the end of a section, a good rule of thumb is to revise the study questions before you begin reading. Try and answer the questions as you move through the chapter–this will help keep your attention and aid you in identifying key information.

Taking notes while you are reading helps you engage in the active learning process and maximizes retention of information. The goal of active note-taking during reading is to help you stay focused on the material and to be able to refer back to notes made while reading to improve retention and study efficiency. Don’t make the mistake of expecting to remember everything you are reading. Taking notes when reading requires effort, time, and energy, but saves you time in the long run.

Highlighting is not recommended while reading because there is no evidence supporting that it aids in reading comprehension or improving test scores.5 Highlighting can be a passive way of engaging with readings. Often, students have a tendency to highlight significantly more information than they need to, making it difficult to review important information in advance of an exam or quiz.

Reflect

After you have finished reading, now is the time to ask yourself some tough questions. How did it go? Were you able to maintain attention or were you easily distracted? Look at your notes and annotations–are they organized and do they make sense? Can you easily summarize the information you learned or teach it to others? What gaps in your knowledge do you still have? What questions do you want to ask?

If you have lingering questions, now is the time to ask. Visiting an instructor’s office hours is one of the most underutilized college resources. Attending office hours allows a student to get their questions answered, better understand concepts, and demonstrate to the instructor that the course is a priority. Find out when your professor’s office hours are (they are often listed in the syllabus), and enjoy the opportunity to connect with your instructor.

You may also benefit from reading it again. Reading the material a second or third time could aid in your understanding and retention of the material. It may be especially helpful to reread the chapter just after the instructor has lectured on it.

It’s Not All Equal

Keep in mind that the best students develop reading skills that are different for different subjects. The main question you want to ask yourself is: Who are you reading for? And what are the questions that drive the discipline? Reading texts, blogs, leisure books and academic articles are all different experiences, and we read them with different mindsets and different strategies. The same is true for textbooks. Reading a mathematics textbook is going to be different than reading a history textbook. Applying the principles in this chapter will help with your reading comprehension, but it’s important to remember that you will need to develop specific reading skills most helpful to the particular subject you are studying.

Citations

- Dillon, Dave. Blueprint for Success in College and Career. OER Commons. https://press.rebus.community/blueprint2/. CC BY 4.0

- Richard T. Vacca and Jo Anne L. Vacca, Content Area Reading: Literacy and Learning across the Curriculum, 6th ed. (Menlo Park, CA: Longman, 1999).

- Joe Cuseo, Viki Fecas and Aaron Thompson, Thriving in College AND Beyond: Research-Based Strategies for Academic Success and Personal Development, (Dubuque, IA: Kendal Hunt Publishing, 2010), 115.

- W. Kintsch, “Text Comprehension, Memory, and Learning,” American Psychologist 49 no. 4 (1994): 294-303, http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.49.4.294.

- Lucy Cui, “MythBusters: Highlighting Helps Me Study,” Psychology in Action, accessed April 27, 2018, https://www.psychologyinaction.org/psychology-in-action-1/2018/1/8/mythbusters-highlighting-helps-me-study.