Distinguish between simple and compound interest, apply their formulas accurately, and explain their relevance in legal contexts such as contracts, settlements, and fiduciary financial analysis.

Ch. 7 Time Value of Money and Valuations

7.2 Interest

Learning Objective

Once you complete this section, you’ll be able to:

Interest is the cost of borrowing money. Borrowers agree to pay interest when they believe the immediate use of funds provides greater value than the cost of repayment. On the other hand, lenders and investors are willing to lend money when they expect the interest received to exceed the value they could derive from using the funds themselves.

Simple Interest

Lawyers encounter Time Value of Money (TVM) in numerous settings. When drafting or reviewing contracts, attorneys must distinguish between simple and compound interest. Simple interest is calculated only on the initial principal amount, not on any interest that accrues over time. The formula for simple interest is:

I = P x r x t

Where:

- I = interest earned

- P = principal (initial amount invested or borrowed)

- r = annual interest rate (as a decimal)

- t = time in years

Example: Simple Interest

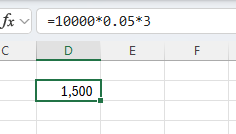

If a client lends $10,000 at a simple interest rate of 5% for 3 years, the total interest earned is:

I = $10,000 x 0.05 x 3 = $1,500

In Excel, the calculation is:

This concept is often used in short-term loans, promissory notes, or certain legal settlements.

Compound Interest

Compound interest, by contrast, adds interest to the principal at regular intervals, meaning future interest calculations are based on both the initial principal and any accumulated interest. It reflects the “interest on interest” effect and is more commonly applied in long-term financial instruments.

The formula for compound interest is:

A = P(1+r/n)^nt

Where:

- A = total amount after interest

- P = principal amount

- r = annual interest rate (as a decimal)

- n = number of compounding periods per year

- t = number of years

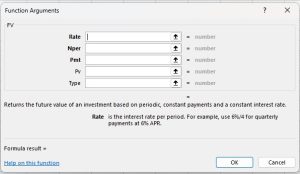

In Excel, you would use the fair value formula to calculate the balance. The Excel calculation would look like: FV(rate, nper, pmt, [pv], [type]) where:

- Rate = interest rate per period (e.g., a monthly compounding rate would take Annual Percentage Rate (APR) divided by 12)

- Nper = total number of payment periods in investment period (e.g., if compounding monthly, take number of years multiplied by 12)

- Pmt = payment made each period; it cannot change over the life of the investment

- Pv = present value, or the lump-sum amount that a series of future payments is worth now

- Type = value representing the timing of payment; payment at beginning of period = 1; payment at end of period = 0 or omitted)

Example: Compound Interest

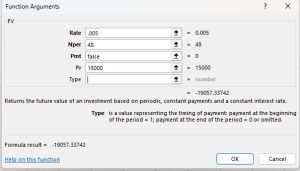

A settlement fund of $15,000 is invested at an annual interest rate of 6%, compounded monthly for 4 years:

A = $15,000 *(1+0.06/12)^12*4 = $15,000*(1.005)^48 = $19,057.34

In Excel, this calculation would be shown as:

This concept is crucial in assessing long-term trust assets, structured settlements, or investment returns for fiduciary litigation.

Summary

Overall, interest represents the cost of borrowing money and plays a central role in the time value of money (TVM), a concept lawyers frequently encounter in financial contracts and settlements. Simple interest is calculated only on the original principal and is typically used in short-term loans and promissory notes, while compound interest accounts for accumulated interest over time and is more common in long-term financial instruments. Understanding the distinction between these two types of interest—along with how to apply their formulas—is essential for attorneys evaluating financial provisions, trust assets, structured settlements, and investment returns.

Homework 7.2.1

Simple Interest in a Promissory Note

Scenario:

Attorney Rivera represents a client who issued a promissory note to a supplier. Under the terms, the supplier agreed to lend $25,000 at 6% simple interest for 18 months (1.5 years). At the end of the term, the full amount plus interest will be repaid.

Requirements:

-

Calculate the total interest owed at maturity.

-

Determine the total repayment amount (principal + interest).

Formula:

Homework 7.2.2

Comparing Simple and Compound Interest in Fiduciary Accounting

Scenario:

A trustee overseeing a deceased client’s estate must distribute funds to two beneficiaries in equal amounts after 5 years. The estate includes $20,000 held in a short-term note earning 5% simple interest, and another $20,000 invested in a bond earning 5% interest compounded annually.

Requirements:

-

Calculate the ending balance for both the simple-interest and compound-interest investments.

-

Compare the results. How much additional income did the compound interest generate?