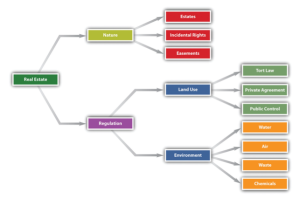

12 Property and Environmental Law

Learning Objectives

After completing the material in this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Identify the difference between personal property and other types of property

- Understand how rights in personal property are acquired and maintained

- Understand how some kinds of personal property can become real property, and how to determine who has rights in fixtures that are part of real property

- Know how ownership of real property is regulated by tort law, by agreement, and by the public interest (through eminent domain)

- Identify the various ways in which environmental laws affect the ownership and use of real property

Recall the beginning of the prior chapter, which discussed the various kinds of property rights, such as intellectual property and real versus personal property. In our legal system, the distinction between real and personal property is significant in several ways. For example, the sale of personal property, but not real property, is governed by Article 2 of the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC). Real estate transactions, by contrast, are governed by the general law of contracts. Suppose goods are exchanged for realty. Section 2-304 of the UCC says that the transfer of the goods and the seller’s obligations with reference to them are subject to Article 2, but not the transfer of the interests in realty nor the transferor’s obligations in connection with them.

The form of transfer depends on whether the property is real or personal. Real property is normally transferred by a deed, which must meet formal requirements dictated by state law. By contrast, transfer of personal property often can take place without any documents at all.

Another difference can be found in the law that governs the transfer of property on death. A person’s heirs depend on the law of the state for distribution of his property if he dies intestate—that is, without a will. Who the heirs are and what their share of the property will be may depend on whether the property is real or personal. For example, widows may be entitled to a different percentage of real property than personal property when their husbands die intestate.

Tax laws also differ in their approach to real and personal property. In particular, the rules of valuation, depreciation, and enforcement depend on the character of the property. Thus real property depreciates more slowly than personal property, and real property owners generally have a longer time than personal property owners to make good unpaid taxes before the state seizes the property.

Acquiring Property Rights

Most legal issues about personal property center on its acquisition. Acquisition by purchase is the most common way we acquire personal property (see contract law!), but there are at least four other ways to legally acquire personal property: (1) possession, (2) finding lost or misplaced property, (3) gift, and (4) confusion.

Possession

It is often said that “possession is nine-tenths of the law.” There is an element of truth to this, but it’s not the whole truth. For our purposes, the more important question is, what is meant by “possession”? Its meaning is not intuitively obvious, as a moment’s reflection will reveal. For example, you might suppose that you possess something when it is physically within your control, but what do you say when a hurricane deposits a boat onto your land? What if you are not even home when this happens? Do you possess the boat? Ordinarily, we would say that you don’t, because you don’t have physical control when you are absent. You may not even have the intention to control the boat; perhaps instead of a fancy speedboat in relatively good shape, the boat is a rust bucket badly in need of repair, and you want it removed from your front yard.

Even the element of physical domination of the object may not be necessary. Suppose you give your new class ring to a friend to examine. Is it in the friend’s possession? No: the friend has custody, not possession, and you retain the right to permit a second friend to take it from her hands. This is different from the case of a bailment, in which the bailor gives possession of an object to the bailee. For example, a garage (a bailee) entrusted with a car for the evening, and not the owner, has the right to exclude others from the car; the owner could not demand that the garage attendants refrain from moving the car around as necessary.

Even the element of physical domination of the object may not be necessary. Suppose you give your new class ring to a friend to examine. Is it in the friend’s possession? No: the friend has custody, not possession, and you retain the right to permit a second friend to take it from her hands. This is different from the case of a bailment, in which the bailor gives possession of an object to the bailee. For example, a garage (a bailee) entrusted with a car for the evening, and not the owner, has the right to exclude others from the car; the owner could not demand that the garage attendants refrain from moving the car around as necessary.

From these examples, we can see that possession or physical control must usually be understood as the power to exclude others from using the object. Otherwise, anomalies arise from the difficulty of physically controlling certain objects. It is more difficult to exercise control over a one-hundred-foot television antenna than a diamond ring. Moreover, in what sense do you possess your household furniture when you are out of the house? Only, we suggest, in the power to exclude others. But this power is not purely a physical one: being absent from the house, you could not physically restrain anyone. Thus the concept of possession must inevitably be mixed with legal rules that do or could control others.

Possession confers ownership in a restricted class of cases only: when no person was the owner at the time the current owner took the object into his possession. The most obvious categories of objects to which this rule of possession applies are wild animals and abandoned goods. The rule requires that the would-be owner actually take possession of the animal or goods; the hunter who is pursuing a particular wild animal has no legal claim until he has actually captured it. Two hunters are perfectly free to pursue the same animal, and whoever actually grabs it will be the owner.

But even this simple rule is fraught with difficulties in the case of both wild animals and abandoned goods. In the case of wild game, fish in a stream, and the like, the general rule is subject to the rights of the owner of the land on which the animals are caught. Thus even if the animals caught by a hunter are wild, as long as they are on another’s land, the landowner’s rights are superior to the hunter’s. Suppose a hunter captures a wild animal, which subsequently escapes, and a second hunter thereafter captures it. Does the first hunter have a claim to the animal? The usual rule is that he does not, for once an animal returns to the wild, ownership ceases.

Lost or Misplaced Property

At common law, a technical distinction arose between lost and misplaced property. An object is lost if the owner inadvertently and unknowingly lets it out of his possession. It is merely misplaced if the owner intentionally puts it down, intending to recover it, even if he subsequently forgets to retrieve it. These definitions are important in considering the old saying “Finders keepers, losers weepers.” This is a misconception that is, at best, only partially true, and more often false. The following hierarchy of ownership claims determines the rights of finders and losers.

First, the owner is entitled to the return of the property unless he has intentionally abandoned it. The finder is said to be a quasi-bailee for the true owner, and as bailee she owes the owner certain duties of care. The finder who knows the owner or has reasonable means of discovering the owner’s identity commits larceny if she holds on to the object with the intent that it be hers. This rule applies only if the finder actually takes the object into her possession. For example, if you spot someone’s wallet on the street you have no obligation to pick it up; but if you do pick it up and see the owner’s name in it, your legal obligation is to return it to the rightful owner. The finder who returns the object is not automatically entitled to a reward, but if the loser has offered a reward, the act of returning it constitutes performance of a unilateral contract. Moreover, if the finder has had expenses in connection with finding the owner and returning the property, she is entitled to reasonable reimbursement as a quasi-bailee. But the rights of the owner are frequently subject to specific statutes.

Second, if the owner fails to claim the property within the time allowed by statute or has abandoned it, then the property goes to the owner of the real estate on which it was found if (1) the finder was a trespasser, (2) the goods are found in a private place (though what exactly constitutes a private place is open to question: is the aisle of a grocery store a private place? the back of the food rack? the stockroom?), (3) the goods are buried, or (4) the goods are misplaced rather than lost.

If none of these conditions apply, then the finder is the owner.

Gift

A gift is a voluntary transfer of property without consideration or compensation. It is distinguished from a sale, which requires consideration. It is distinguished from a promise to give, which is a declaration of an intention to give in the future rather than a present transfer. It is distinguished from a testamentary disposition (will), which takes effect only upon death, not upon the preparation of the documents. Two other distinctions are worth noting. An inter vivos (enter VYE vos) gift is one made between living persons without conditions attached. A causa mortis (KAW zuh mor duz) gift is made by someone contemplating death in the near future.

To make an effective gift inter vivos or causa mortis, the law imposes three requirements: (1) the donor must deliver a deed or object to the donee; (2) the donor must actually intend to make a gift, and (3) the donee must accept.

Delivery

Although it is firmly established that the object be delivered, it is not so clear what constitutes delivery. On the face of it, the requirement seems to be that the object must be transferred to the donee’s possession. Suppose your friend tells you he is making a gift to you of certain books that are lying in a locked trunk. If he actually gives you the trunk so that you can carry it away, a gift has been made. Suppose, however, that he had merely given you the key, so that you could come back the next day with your car. If this were the sole key, the courts would probably construe the transfer of the key as possession of the trunk. Suppose, instead, that the books were in a bank vault and the friend made out a legal document giving both you and him the power to take from the bank vault. This would not be a valid gift, since he retained power over the goods.

Intent

The intent to make a gift must be an intent to give the property at the present time, not later. For example, suppose a person has her savings account passbook put in her name and a friend’s name, intending that on her death the friend will be able to draw out whatever money is left. She has not made a gift, because she did not intend to give the money when she changed the passbook. The intent requirement can sometimes be sidestepped if legal title to the object is actually transferred, postponing to the donee only the use or enjoyment of the property until later. Had the passbook been made out in the name of the donee only and delivered to a third party to hold until the death of the donor, then a valid gift may have been made. Although it is sometimes difficult to discern this distinction in practice, a more accurate statement of the rule of intent is this: Intention to give in the future does not constitute the requisite intent, whereas present gifts of future interests will be upheld.

Acceptance

In the usual case, the rule requiring acceptance poses no difficulties. A friend hands you a new book and says, “I would like you to have this.” Your taking the book and saying “thank-you” is enough to constitute your acceptance. But suppose that the friend had given you property without your knowing it. For example, a secret admirer puts her stock certificates jointly in your name and hers without telling you. Later, you marry someone else, and she asks you to transfer the certificates back to her name. This is the first you have heard of the transaction. Has a gift been made? The usual answer is that even though you had not accepted the stock when the name change was made, the transaction was a gift that took effect immediately, subject to your right to repudiate when you find out about it. If you do not reject the gift, you have joint rights in the stock. But if you expressly refuse to accept a gift or indicate in some manner that you might not have accepted it, then the gift is not effective. For example, suppose you are running for office. A lobbyist whom you despise gives you a donation. If you refuse the money, no gift has been made.

Confusion

“Confusion” occurs not just as you’re reading this chapter. It also denotes when goods of different owners, while maintaining their original form, are commingled. A common example is the intermingling of grain in a silo. But goods that are identifiable as belonging to a particular person—branded cattle, for instance—are not confused, no matter how difficult it may be to separate herds that have been put together.[1]

“Confusion” occurs not just as you’re reading this chapter. It also denotes when goods of different owners, while maintaining their original form, are commingled. A common example is the intermingling of grain in a silo. But goods that are identifiable as belonging to a particular person—branded cattle, for instance—are not confused, no matter how difficult it may be to separate herds that have been put together.[1]

When the goods are identical, no particular problem of division arises. Assuming that each owner can show how much he has contributed to the confused mass, he is entitled to that quantity, and it does not matter which particular grains or kernels he extracts. So if a person, seeing a container of grain sitting on the side of the road, mistakes it for his own and empties it into a larger container in his truck, the remedy is simply to restore a like quantity to the original owner. When owners of like substances consent to have those substances combined (such as in a grain silo), they are said to be tenants in common, holding a proportional share in the whole.

In the case of willful confusion of goods, many courts hold that the wrongdoer forfeits all his property unless he can identify his particular property. Other courts have modified this harsh rule by shifting the burden of proof to the wrongdoer, leaving it up to him to claim whatever he can establish was his. If he cannot establish what was his, then he will forfeit all. Likewise, when the defendant has confused the goods negligently, without intending to do so, most courts will tend to shift to the defendant the burden of proving how much of the mass belongs to him.

Fixtures

A fixture is an object that was once personal property but that has become so affixed to land or structures that it is considered legally a part of the real property. For example, a stove bolted to the floor of a kitchen and connected to the gas lines is usually considered a fixture, either in a contract for sale, or for testamentary transfer (by will). For tax purposes, fixtures are treated as real property.

Obviously, no clear line can be drawn between what is and what is not a fixture. In general, the courts look to three tests to determine whether a particular object has become a fixture: annexation, adaptation, and intention.

Annexation

The object must be annexed or affixed to the real property. A door on a house is affixed. Suppose the door is broken and the owner has purchased a new door made to fit, but the house is sold before the new door is installed. Most courts would consider that new door a fixture under a rule of constructive annexation. Sometimes courts have said that an item is a fixture if its removal would damage the real property, but this test is not always followed. Must the object be attached with nails, screws, glue, bolts, or some other physical device? In one case, the court held that a four-ton statue was sufficiently affixed merely by its weight.[2]

Adaptation

Another test is whether the object is adapted to the use or enjoyment of the real property. Examples are home furnaces, power equipment in a mill, and computer systems in bank buildings.

Intention

Recent decisions suggest that the controlling test is whether the person who actually annexes the object intends by so doing to make it a permanent part of the real estate. The intention is usually deduced from the circumstances, not from what a person might later say her intention was. If an owner installs a heating system in her house, the law will presume she intended it as a fixture because the installation was intended to benefit the house; she would not be allowed to remove the heating system when she sold the house by claiming that she had not intended to make it a fixture.

Key Takeaways

Property is difficult to define conclusively, and there are many different classifications of property. There can be public property as well as private property, tangible property as well as intangible property, and, most importantly, real property as well as personal property. These are important distinctions, with many legal consequences.

Other than outright purchase of personal property, there are various ways in which to acquire legal title. Among these are possession, gift, accession, confusion, and finding property that is abandoned, lost, or mislaid, especially if the abandoned, lost, or mislaid property is found on real property that you own.

Personal property is often converted to real property when it is affixed to real property. There are three tests that courts use to determine whether a particular object has become a fixture and thus has become real property: annexation, adaptation, and intention.

Exercises

- Kristen buys a parcel of land on Marion Street, a new and publicly maintained roadway. Her town’s ordinances say that each property owner on a public street must also provide a sidewalk within ten feet of the curb. A year after buying the parcel, Kristen commissions a house to be built on the land, and the contractor begins by building a sidewalk in accordance with the town’s ordinance. Is the sidewalk public property or private property? If it snows, and if Kristen fails to remove the snow and it melts and ices over and a pedestrian slips and falls, who is responsible for the pedestrian’s injuries?

- When can private property become public property? Does public property ever become private property?

- Dan captures a wild boar on US Forest Service land. He takes it home and puts it in a cage, but the boar escapes and runs wild for a few days before being caught by Romero, some four miles distant from Dan’s house. Romero wants to keep the boar. Does he “own” it? Or does it belong to Dan, or to someone else?

- Harriet finds a wallet in the college library, among the stacks. The wallet has $140 in it, but no credit cards or identification. The library has a lost and found at the circulation desk, and the people at the circulation desk are honest and reliable. The wallet itself is unique enough to be identified by its owner. (a) Who owns the wallet and its contents? (b) As a matter of ethics, should Harriet keep the money if the wallet is “legally” hers?

- Jim and Donna Stoner contract to sell their house in Rochester, Michigan, to Clem and Clara Hovenkamp. Clara thinks that the decorative chandelier in the entryway is lovely and gives the house an immediate appeal. The chandelier was a gift from Donna’s mother, “to enhance the entryway” and provide “a touch of beauty” for Jim and Donna’s house. Clem and Clara assume that the chandelier will stay, and nothing specific is mentioned about the chandelier in the contract for sale. Clem and Clara are shocked when they move in and find the chandelier is gone. Have Jim and Donna breached their contract of sale?

Estates

We now move on to the law governing real property in particular. In property law, an estate is an interest in real property, ranging from absolute dominion and control to bare possession. Ordinarily when we think of property, we think of only one kind: absolute ownership. The owner of a car has the right to drive it where and when she wants, rebuild it, repaint it, and sell it or scrap it. The notion that the owner might lose her property when a particular event happens is foreign to our concept of personal property. Not so with real property. You would doubtless think it odd if you were sold a used car subject to the condition that you not paint it a different color—and that if you did, you would automatically be stripped of ownership. But land can be sold that way. Land and other real property can be divided into many categories of interests, as we will see. (Be careful not to confuse the various types of interests in real property with the forms of ownership, such as joint tenancy. An interest in real property that amounts to an estate is a measure of the degree to which a thing is owned; the form of ownership deals with the particular person or persons who own it.)

The common law distinguishes estates along two main axes: (1) freeholds versus leaseholds and (2) present versus future interests. A freehold estate is an interest in land that has an uncertain duration. The freehold can be outright ownership—called the fee simple absolute—or it can be an interest in the land for the life of the possessor; in either case, it is impossible to say exactly how long the estate will last. In the case of one who owns property outright, her estate will last until she sells or transfers it; in the case of a life estate, it will last until the death of the owner or another specified individual. A leasehold estate is one whose termination date is usually known. A one-year lease, for example, will expire precisely at the time stated in the lease agreement.

A present estate is one that is currently owned and enjoyed; a future estate is one that will come into the owner’s possession upon the occurrence of a particular event.

Present Estates

Fee Simple Absolute

The strongest form of ownership is known as the fee simple absolute (or fee simple, or merely fee). This is what we think of when we say that someone “owns” the land. As one court put it, “The grant of a fee in land conveys to the grantee complete ownership, immediately and forever, with the right of possession from boundary to boundary and from the center of the earth to the sky, together with all the lawful uses thereof.”[3] Although the fee simple may be encumbered by a mortgage (you may borrow money against the equity in your home) or an easement (you may grant someone the right to walk across your backyard), the underlying control is in the hands of the owner. Though it was once a complex matter in determining whether a person had been given a fee simple interest, today the law presumes that the estate being transferred is a fee simple, unless the conveyance expressly states to the contrary. (In her will, Lady Gaga grants her five-thousand-acre ranch “to my screen idol, Tilda Swinton.” On the death of Lady Gaga, Swinton takes ownership of the ranch outright in fee simple absolute.)

Fee Simple Defeasible

Not every transfer of real property creates a fee simple absolute. Some transfers may limit the estate. Any transfer specifying that the ownership will terminate upon a particular happening is known as a fee simple defeasible. Suppose, for example, that Mr. Warbucks conveys a tract of land “to Miss Florence Nightingale, for the purpose of operating her hospital and for no other purpose. Conveyance to be good as long as hospital remains on the property.” This grant of land will remain the property of Miss Nightingale and her heirs as long as she and they maintain a hospital. When they stop doing so, the land will automatically revert to Mr. Warbucks or his heirs, without their having to do anything to regain title. Note that the conveyance of land could be perpetual but is not absolute, because it will remain the property of Miss Nightingale only so long as she observes the conditions in the grant.

Life Estates

An estate measured by the life of a particular person is called a life estate. A conventional life estate is created privately by the parties themselves. A conventional life estate is created privately by the parties themselves. The simplest form is that conveyed by the following words: “to Penny for life.” Penny becomes a life tenant; as such, she is the owner of the property and may occupy it for life or lease it or even sell it, but the new tenant or buyer can acquire only as much as Penny has to give, which is ownership for her life (i.e., all she can sell is a life estate in the land, not a fee simple absolute). If Penny sells the house and dies a month later, the buyer’s interest would terminate. A life estate may be based on the life of someone other than the life tenant: “to Penny for the life of Leonard.”

The life tenant may use the property as though he were the owner in fee simple absolute with this exception: he may not act so as to diminish the value of the property that will ultimately go to the remainderman—the person who will become owner when the life estate terminates. The life tenant must pay the life estate for ordinary upkeep of the property, but the remainderman is responsible for extraordinary repairs.

Some life estates are created by operation of law and are known as legal life estates. The most common form is a widow’s interest in the real property of her husband. In about one-third of the states, a woman is entitled to dower,[4] a right to a percentage (often one-third) of the property of her husband when he dies. Most of these states give a widower a similar interest in the property of his deceased wife. Dower is an alternative to whatever is bequeathed in the will; the widow has the right to elect the share stated in the will or the share available under dower. To prevent the dower right from upsetting the interests of remote purchasers, the right may be waived on sale by having the spouse sign the deed.

Future Estates

To this point, we have been considering present estates. But people also can have future interests in real property. Despite the implications of its name, the future interest is owned now but is not available to be used or enjoyed now. For the most part, future interests may be bought and sold, just as land held in fee simple absolute may be bought and sold. There are several classes of future interests, but in general there are two major types: reversion and remainder.

Reversion

A reversion arises whenever the estate transferred has a duration less than that originally owned by the transferor. A typical example of a simple reversion is that which arises when a life estate is conveyed. The ownership conveyed is only for the life; when the life tenant dies, the ownership interest reverts to the grantor. Suppose the grantor has died in the meantime. Who gets the reversion interest? Since the reversion is a class of property that is owned now, it can be inherited, and the grantor’s heirs would take the reversion at the subsequent death of the life tenant.

A reversion arises whenever the estate transferred has a duration less than that originally owned by the transferor. A typical example of a simple reversion is that which arises when a life estate is conveyed. The ownership conveyed is only for the life; when the life tenant dies, the ownership interest reverts to the grantor. Suppose the grantor has died in the meantime. Who gets the reversion interest? Since the reversion is a class of property that is owned now, it can be inherited, and the grantor’s heirs would take the reversion at the subsequent death of the life tenant.

Remainder

The transferor need not keep the reversion interest for himself. He can give that interest to someone else, in which case it is known as a remainder[5] interest, because the remainder of the property is being transferred. Suppose the transferor conveys land with these words: “to Penny for life and then to Leonard.” Penny has a life estate; the remainder goes to Leonard in fee simple absolute. Leonard is said to have a vested remainder interest, because on Penny’s death, he or his heirs will automatically become owners of the property. Some remainder interests are contingent—and are therefore known as contingent remainder interests—on the happening of a certain event: “to my mother for her life, then to my sister if she marries Harold before my mother dies.” The transferor’s sister will become the owner of the property in fee simple only if she marries Harold while her mother is alive; otherwise, the property will revert to the transferor or his heirs. The number of permutations of reversions and remainders can become quite complex, far more than we have space to discuss in this text.

Key Takeaways

An estate is an interest in real property. Estates are of many kinds, but one generic difference is between ownership estates and possessory estates. Fee simple estates and life estates are ownership estates, while leasehold interests are possessory. Among ownership estates, the principal division is between present estates and future estates. An owner of a future estate has an interest that can be bought and sold and that will ripen into present possession at the end of a period of time, at the end of the life of another, or with the happening of some contingent event.

Exercises

- Jessa owns a house and lot on 9th Avenue. She sells the house to the Hartley family, who wish to have a conveyance from her that says, “to Harriet Hartley for life, remainder to her son, Alexander Sandridge.” Alexander is married to Chloe, and they have three children, Carmen, Sarah, and Michael. Who has a future interest, and who has a present interest? What is the correct legal term for Harriet’s estate? Does Alexander, Carmen, Sarah, or Michael have any part of the estate at the time Jessa conveys to Harriet using the stated language?

- After Harriet dies, Alexander wants to sell the property. Alexander and Chloe’s children are all eighteen years of age or older. Can he convey the property by his signature alone? Who else needs to sign?

Real Estate Ownership and Possession

Learning Objectives

- Understand that property owners have certain rights in the airspace above their land, in the minerals beneath their land, and even in water that adjoins their land.

- Explain the difference between an easement and a license.

- Describe the ways in which easements can be created.

Rights to Soil, Air, and Water

Rights to Airspace

The traditional rule was stated by Lord Coke: “Whoever owns the soil owns up to the sky.” This traditional rule remains valid today, but its application can cause problems. A simple example would be a person who builds an extension to the upper story of his house so that it hangs out over the edge of his property line and thrusts into the airspace of his neighbor. That would clearly be an encroachment on the neighbor’s property. But is it trespass when an airplane—or an earth satellite—flies over your backyard? Obviously, the courts must balance the right to travel against landowners’ rights. In U.S. v. Causby,[6] the Court determined that flights over private land may constitute a diminution in the property value if they are so low and so frequent as to be a direct and immediate interference with the enjoyment and use of land.

Rights to the Depths

Lord Coke’s dictum applies to the depths as well as the sky. The owner of the surface has the right to the oil, gas, and minerals below it, although this right can be severed and sold separately. Perplexing questions may arise in the case of oil and gas, which can flow under the surface. Some states say that oil and gas can be owned by the owner of the surface land; others say that they are not owned until actually extracted—although the property owner may sell the exclusive right to extract them from his land. But states with either rule recognize that oil and gas are capable of being “captured” by drilling that causes oil or gas from under another plot of land to run toward the drilled hole. Since the possibility of capture can lead to wasteful drilling practices as everyone nearby rushes to capture the precious commodities, many states have enacted statutes requiring landowners to share the resources.

Rights to Water

The right to determine how bodies of water will be used depends on basic property rules. Two different approaches to water use in the United States—eastern and western—have developed over time. Eastern states, where water has historically been more plentiful, have adopted the so-called riparian rights theory, which itself can take two forms. Riparian refers to land that includes a part of the bed of a waterway or that borders on a public watercourse. A riparian owner is one who owns such land. What are the rights of upstream and downstream owners of riparian land regarding use of the waters? One approach is the “natural flow” doctrine: Each riparian owner is entitled to have the river or other waterway maintained in its natural state. The upstream owner may use the river for drinking water or for washing but may not divert it to irrigate his crops or to operate his mill if doing so would materially change the amount of the flow or the quality of the water. Virtually all eastern states today are not so restrictive and rely instead on a “reasonable use” doctrine, which permits the benefit to be derived from use of the waterway to be weighed against the gravity of the harm.

In contrast to riparian rights doctrines, western states have adopted the prior appropriation doctrine. This rule looks not to equality of interests but to priority in time: first in time is first in right. The first person to use the water for a beneficial purpose has a right superior to latecomers. This rule applies even if the first user takes all the water for his own needs and even if other users are riparian owners. This rule developed in water-scarce states in which development depended on incentives to use rather than hoard water. Today, the prior appropriation doctrine has come under criticism because it gives incentives to those who already have the right to the water to continue to use it profligately, rather than to those who might develop more efficient means of using it.

Easements: Rights in the Lands of Others

Definition

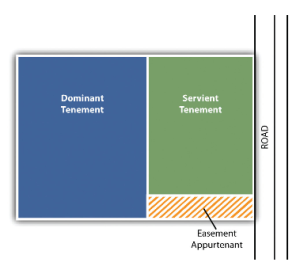

An easement is an interest in land created by agreement that permits one person to make use of another’s estate. This interest can extend to a profit, the taking of something from the other’s land. Though the common law once distinguished between an easement and profit, today the distinction has faded, and profits are treated as a type of easement. An easement must be distinguished from a mere license[7], which is permission, revocable at the will of the owner, to make use of the owner’s land. An easement is an estate; a license is personal to the grantee and is not assignable.

An easement is an interest in land created by agreement that permits one person to make use of another’s estate. This interest can extend to a profit, the taking of something from the other’s land. Though the common law once distinguished between an easement and profit, today the distinction has faded, and profits are treated as a type of easement. An easement must be distinguished from a mere license[7], which is permission, revocable at the will of the owner, to make use of the owner’s land. An easement is an estate; a license is personal to the grantee and is not assignable.

The two main types of easements are affirmative and negative. An affirmative easement gives a landowner the right to use the land of another (e.g., crossing it or using water from it), while a negative easement,[8] by contrast, prohibits the landowner from using his land in ways that would affect the holder of the easement. For example, the builder of a solar home would want to obtain negative easements from neighbors barring them from building structures on their land that would block sunlight from falling on the solar home. With the growth of solar energy, some states have begun to provide stronger protection by enacting laws that regulate one’s ability to interfere with the enjoyment of sunlight. These laws range from a relatively weak statute in Colorado, which sets forth rules for obtaining easements, to the much stronger statute in California, which says in effect that the owner of a solar device has a vested right to continue to receive the sunlight.

Another important distinction is made between easements appurtenant and easements in gross. An easement appurtenant benefits the owner of adjacent land. The easement is thus appurtenant to the holder’s land. The benefited land is called the dominant tenement, and the burdened land—that is, the land subject to the easement—is called the servient tenement. An easement in gross is granted independent of the easement holder’s ownership or possession of land. It is simply an independent right—for example, the right granted to a local delivery service to drive its trucks across a private roadway to gain access to homes at the other end.

Unless it is explicitly limited to the grantee, an easement appurtenant “runs with the land.” That is, when the dominant tenement is sold or otherwise conveyed, the new owner automatically owns the easement. A commercial easement in gross may be transferred—for instance, easements to construct pipelines, telegraph and telephone lines, and railroad rights of way. However, most noncommercial easements in gross are not transferable, being deemed personal to the original owner of the easement. Rochelle sells her friend Mrs. Nanette—who does not own land adjacent to Rochelle—an easement across her country farm to operate skimobiles during the winter. The easement is personal to Mrs. Nanette; she could not sell the easement to anyone else.

Creation

Easements may be created by express agreement, either in deeds or in wills. The owner of the dominant tenement may buy the easement from the owner of the servient tenement or may reserve the easement for himself when selling part of his land. But courts will sometimes allow implied easements under certain circumstances. For instance, if the deed refers to an easement that bounds the premises—without describing it in any detail—a court could conclude that an easement was intended to pass with the sale of the property.

An easement can also be implied from prior use. Suppose a seller of land has two lots, with a driveway connecting both lots to the street. The only way to gain access to the street from the back lot is to use the driveway, and the seller has always done so. If the seller now sells the back lot, the buyer can establish an easement in the driveway through the front lot if the prior use was (1) apparent at the time of sale, (2) continuous, and (3) reasonably necessary for the enjoyment of the back lot. The rule of implied easements through prior use operates only when the ownership of the dominant and servient tenements was originally in the same person.

Use of the Easement

The servient owner may use the easement—remember, it is on or under or above his land—as long as his use does not interfere with the rights of the easement owner. Suppose you have an easement to walk along a path in the woods owned by your neighbor and to swim in a private lake that adjoins the woods. At the time you purchased the easement, your neighbor did not use the lake. Now he proposes to swim in it himself, and you protest. You would not have a sound case, because his swimming in the lake would not interfere with your right to do so. But if he proposed to clear the woods and build a mill on it, obliterating the path you took to the lake and polluting the lake with chemical discharges, then you could obtain an injunction to bar him from interfering with your easement.

The owner of the dominant tenement is not restricted to using his land as he was at the time he became the owner of the easement. The courts will permit him to develop the land in some “normal” manner. For example, an easement on a private roadway for the benefit of a large estate up in the hills would not be lost if the large estate were ultimately subdivided and many new owners wished to use the roadway; the easement applies to the entire portion of the original dominant tenement, not merely to the part that abuts the easement itself. However, the owner of an easement appurtenant to one tract of land cannot use the easement on another tract of land, even if the two tracts are adjacent.

Exercises

- Steve Hannaford farms in western Nebraska. The farm has passed to succeeding generations of Hannafords, who use water from the North Platte River for irrigation purposes. The headlands of the North Platte are in Colorado, but use of the water from the North Platte by Nebraskans preceded use of the water by settlers in Colorado. What theory of water rights governs Nebraska and Colorado residents? Can the state of Colorado divert and use water in such a way that less of it reaches western Nebraska and the Hannaford farm? Why or why not?

- Jamie decides to put solar panels on the south face of his roof. Jamie lives on a block of one- and two-bedroom bungalows in South Miami, Florida. In 2009, someone purchases the house next door and within two years decides to add a second and third story. This proposed addition will significantly decrease the utility of Jamie’s solar array. Does Jamie have any rights that would limit what his new neighbors can do on their own land?

- Beth Delaney owns property next to Kerry Plemmons. The deed to Delaney’s property notes that she has access to a well on the Plemmons property “to obtain water for household use.” The well has been dry for many generations and has not been used by anyone on the Plemmons property or the Delaney property for as many generations. The well predated Plemmons’s ownership of the property; as the servient tenement, the Plemmons property was burdened by this easement dating back to 1898. Plemmons hires a company to dig a very deep well near one of his outbuildings to provide water for his horses. The location is one hundred yards from the old well. Does the Delaney property have any easement to use water from the new well?

Regulation of Land Use

Learning Objectives

- Compare the various ways in which law limits or restricts the right to use your land in any way that you decide is best for you.

- Distinguish between regulation by common law and regulation by public acts such as zoning or eminent domain.

- Understand that property owners may restrict the uses of land by voluntary agreement, subject to important public policy considerations.

Land use regulation falls into three broad categories: (1) restriction on the use of land through tort law, (2) private regulation by agreement, and (3) public ownership or regulation through the powers of eminent domain and zoning.

Regulation of Land Use by Tort Law

Tort law is used to regulate land use in two ways: (1) The owner may become liable for certain activities carried out on the real estate that affect others beyond the real estate. (2) The owner may be liable to persons who, upon entering the real estate, are injured.

Landowner’s Activities

The two most common torts in this area are nuisance and trespass. A common-law nuisance is an interference with the use and enjoyment of one’s land. Examples of nuisances are excessive noise (especially late at night), polluting activities, and emissions of noxious odors. But the activity must produce substantial harm, not fleeting, minor injury, and it must produce those effects on the reasonable person, not on someone who is peculiarly allergic to the complained-of activity. A person who suffered migraine headaches at the sight of croquet being played on a neighbor’s lawn would not likely win a nuisance lawsuit. While the meaning of nuisance is difficult to define with any precision, this common-law cause of action is a primary means for landowners to obtain damages for invasive environmental harms.

A trespass is the wrongful physical invasion of or entry upon land possessed by another. Loud noise blaring out of speakers in the house next door might be a nuisance but could not be a trespass, because noise is not a physical invasion. But spraying pesticides on your gladiolas could constitute a trespass on your neighbor’s property if the pesticide drifts across the boundary.

Nuisance and trespass are complex theories, a full explanation of which would consume far more space than we have. What is important to remember is that these torts are two-edged swords. In some situations, the landowner himself will want to use these theories to sue trespassers or persons creating a nuisance, but in other situations, the landowner will be liable under these theories for his own activities.

Injury to Persons Entering the Real Estate

Traditionally, liability for injury has depended on the status of the person who enters the real estate.

Trespassers

If the person is an intruder without permission—a trespasser—the landowner owes him no duty of care unless he knows of the intruder’s presence, in which case the owner must exercise reasonable care in his activities and warn of hidden dangers on his land of which he is aware.[9] A known trespasser is someone whom the landowner actually sees on the property or whom he knows frequently intrudes on the property, as in the case of someone who habitually walks across the land. If a landowner knows that people frequently walk across his property and one day he puts a poisonous chemical on the ground to eliminate certain insects, he is obligated to warn those who continue to walk on the grounds. Intentional injury to known trespassers is not allowed, even if the trespasser is a criminal intent on robbery, for the law values human life above property rights.

Children

If the trespasser is a child, a different rule applies in most states. This is the doctrine of attractive nuisance. Originally this rule was enunciated to deal with cases in which something on the land attracted the child to it, like a swimming pool. In recent years, most courts have dropped the requirement that the child must have been attracted to the danger. Instead, the following elements of proof are necessary to make out a case of attractive nuisance (Restatement of Torts, Section 339):

- The child must have been injured by a structure or other artificial condition.

- The possessor of the land (not necessarily the owner) must have known or should have known that young children would be likely to trespass.

- The possessor must have known or should have known that the artificial condition exists and that it posed an unreasonable risk of serious injury.

- The child must have been too young to appreciate the danger that the artificial condition posed.

- The risk to the child must have far outweighed the utility of the artificial condition to the possessor.

- The possessor did not exercise reasonable care in protecting the child or eliminating the danger.

Old refrigerators, unfenced pools, or mechanisms that a curious child would find inviting are all examples of attractive nuisance.

Private Regulation of Land Use by Agreement

A restrictive covenant is an agreement regarding the use of land that “runs with the land.” In effect, it is a contractual promise that becomes part of the property and that binds future owners. Violations of covenants can be redressed in court in suits for damages or injunctions but will not result in reversion of the land to the seller.

Usually, courts construe restrictive covenants narrowly—that is, in a manner most conducive to free use of the land by the ultimate owner (the person against whom enforcement of the covenant is being sought). Sometimes, even when the meaning of the covenant is clear, the courts will not enforce it. For example, when the character of a neighborhood changes, the courts may declare the covenant a nullity. Thus a restriction on a one-acre parcel to residential purposes was voided when in the intervening thirty years a host of businesses grew up around it, including a bowling alley, restaurant, poolroom, and sewage disposal plant.[10]

An important nullification of restrictive covenants came in 1947 when the US Supreme Court struck down as unconstitutional racially restrictive covenants, which barred blacks and other minorities from living on land so burdened. The Supreme Court reasoned that when a court enforces such a covenant, it acts in a discriminatory manner (barring blacks but not whites from living in a home burdened with the covenant) and thus violates the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of equal protection of the laws.[11]

Public Control of Land Use through Eminent Domain

The government may take private property for public purposes.[12] Its power to do so is known as eminent domain. The power of eminent domain is subject to constitutional limitations. Under the Fifth Amendment, the property must be put to public use, and the owner is entitled to “just compensation” for his loss. These requirements are sometimes difficult to apply.

Public Use

The requirement of public use normally means that the property will be useful to the public once the state has taken possession—for example, private property might be condemned to construct a highway. Although not allowed in most circumstances, the government could even condemn someone’s property in order to turn around and sell it to another individual, if a legitimate public purpose could be shown. For example, a state survey in the mid-1960s showed that the government owned 49 percent of Hawaii’s land. Another 47 percent was controlled by seventy-two private landowners. Because this concentration of land ownership (which dated back to feudal times) resulted in a critical shortage of residential land, the Hawaiian legislature enacted a law allowing the government to take land from large private estates and resell it in smaller parcels to homeowners. In 1984, the US Supreme Court upheld the law, deciding that the land was being taken for a public use because the purpose was “to attack certain perceived evils of concentrated property ownership.”[13] Although the use must be public, the courts will not inquire into the necessity of the use or whether other property might have been better suited. It is up to government authorities to determine whether and where to build a road, not the courts.

The limits of public use were amply illustrated in the Supreme Court’s 2002 decision of Kelo v. New London,[14] in which Mrs. Kelo’s house was condemned so that the city of New London, in Connecticut, could create a marina and industrial park to lease to Pfizer Corporation. The city’s motives were to create a higher tax base for property taxes. The Court, following precedent in Midkiff and other cases, refused to invalidate the city’s taking on constitutional grounds. Reaction from states was swift; many states passed new laws restricting the bases for state and municipal governments to use powers of eminent domain, and many of these laws also provided additional compensation to property owners whose land was taken.

Just Compensation

The owner is ordinarily entitled to the fair market value of land condemned under eminent domain. This value is determined by calculating the most profitable use of the land at the time of the taking, even though it was being put to a different use. The owner will have a difficult time collecting lost profits; for instance, a grocery store will not usually be entitled to collect for the profits it might have made during the next several years, in part because it can presumably move elsewhere and continue to make profits and in part because calculating future profits is inherently speculative.

Taking

The most difficult question in most modern cases is >whether the government has in fact “taken” the property. This is easy to answer when the government acquires title to the property through condemnation proceedings. But more often, a government action is challenged when a law or regulation inhibits the use of private land. Suppose a town promulgates a setback ordinance, requiring owners along city sidewalks to build no closer to the sidewalk than twenty feet. If the owner of a small store had only twenty-five feet of land from the sidewalk line, the ordinance would effectively prevent him from housing his enterprise, and the ordinance would be a taking. Challenging such ordinances can sometimes be difficult under traditional tort theories because the government is immune from suit in some of these cases. Instead, a theory of inverse condemnation has developed, in which the plaintiff private property owner asserts that the government has condemned the property, though not through the traditional mechanism of a condemnation proceeding.

Key Takeaways

Land use regulation can mean (1) restrictions on the use of land through tort law, (2) private regulation—by agreement, or (3) regulation through powers of eminent domain or zoning.

Exercises

- Give one example of the exercise of eminent domain. In order to exercise its power under eminent domain, must the government actually take eventual ownership of the property that is “taken”?

- Felix Unger is an adult, trespassing for the first time on Alan Spillborghs’s property. Alan has been digging a deep grave in his backyard for his beloved Saint Bernard, Maximilian, who has just died. Alan stops working on the grave when it gets dark, intending to return to the task in the morning. He seldom sees trespassers cutting through his backyard. Felix, in the dark, after visiting the local pub, decides to take a shortcut through Alan’s yard and falls into the grave. He breaks his leg. What is the standard of care for Alan toward Felix or other infrequent trespassers? If Alan has no insurance for this accident, would the law make Alan responsible?

- Atlantic Cement owns and operates a cement plant in New York State. Nearby residents are exposed to noise, soot, and dust and have experienced lowered property values as a result of Atlantic Cement’s operations. Is there a common-law remedy for nearby property owners for losses occasioned by Atlantic’s operations? If so, what is it called?

Environmental Law

Learning Objectives

- Describe the major federal laws that govern business activities that may adversely affect air quality and water quality.

- Describe the major federal laws that govern waste disposal and chemical hazards including pesticides.

In one sense, environmental law is very old. Medieval England had smoke control laws that established the seasons when soft coal could be burned. Nuisance laws give private individuals a limited control over polluting activities of adjacent landowners. But a comprehensive set of US laws directed toward general protection of the environment is largely a product of the past quarter-century, with most of the legislative activity stemming from the late 1960s and later, when people began to perceive that the environment was systematically deteriorating from assaults by rapid population growth and greatly increased automobile driving, vast proliferation of factories that generate waste products, and a sharp rise in the production of toxic materials. Two of the most significant developments in environmental law came in 1970, when the National Environmental Policy Act took effect and the Environmental Protection Agency became the first of a number of new federal administrative agencies to be established during the decade.

National Environmental Policy Act

Signed into law by President Nixon on January 1, 1970, the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) declared that it shall be the policy of the federal government, in cooperation with state and local governments, “to create and maintain conditions under which man and nature can exist in productive harmony, and fulfill the social, economic, and other requirements of present and future generations of Americans.. . . The Congress recognizes that each person should enjoy a healthful environment and that each person has a responsibility to contribute to the preservation and enhancement of the environment.”

The most significant aspect of NEPA is its requirement that federal agencies prepare an environmental impact statement332 in every recommendation or report on proposals for legislation and whenever undertaking a major federal action that significantly affects environmental quality. The statement must (1) detail the environmental impact of the proposed action, (2) list any unavoidable adverse impacts should the action be taken, (3) consider alternatives to the pro- posed action, (4) compare short-term and long-term consequences, and (5) describe irreversible commitments of resources. Unless the impact statement is prepared, the project can be enjoined from proceeding. Note that NEPA does not apply to purely private activities but only to those proposed to be carried out in some manner by federal agencies.

Environmental Protection Agency

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has been in the forefront of the news since its creation in 1970. Charged with monitoring environmental practices of industry, assisting the government and private business to halt environmental deterioration, promulgating regulations consistent with federal environmental policy, and policing industry for violations of the various federal environmental statutes and regulations, the EPA has had a pervasive influence on American business. Business Week noted the following in 1977: “Cars rolling off Detroit’s assembly line now have antipollution devices as standard equipment. The dense black smokestack emissions that used to symbolize industrial prosperity are rare, and illegal, sights. Plants that once blithely ran discharge water out of a pipe and into a river must apply for permits that are almost impossible to get unless the plants install expensive water treatment equipment. All told, the EPA has made a sizable dent in man-made environmental filth.”[15]

The EPA is especially active in regulating water and air pollution and in overseeing the disposition of toxic wastes and chemicals. Clean Water Act Legislation governing the nation’s waterways goes back a long time. The first federal water pollution statute was the Rivers and Harbors Act of 1899. Congress enacted new laws in 1948, 1956, 1965, 1966, and 1970. But the centerpiece of water pollution enforcement is the Clean Water Act of 1972 (technically, the Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments of 1972), as amended in 1977 and by the Water Quality Act of 1987. The Clean Water Act is designed to restore and maintain the “chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the Nation’s waters.”33 United States Code, Section 1251. It operates on the states, requiring them to designate the uses of every significant body of water within their borders (e.g., for drinking water, recreation, commercial fishing) and to set water quality standards to reduce pollution to levels appropriate for each use.

Clean Water Act

Congress only has power to regulate interstate commerce, and so the Clean Water Act is applicable only to “navigable waters” of the United States. This has led to disputes over whether the act can apply, say, to an abandoned gravel pit that has no visible connection to navigable waterways, even if the gravel pit provides habitat for migratory birds. In Solid Waste Agency of Northern Cook County v. Army Corps of Engineers, the US Supreme Court said no.

Congress only has power to regulate interstate commerce, and so the Clean Water Act is applicable only to “navigable waters” of the United States. This has led to disputes over whether the act can apply, say, to an abandoned gravel pit that has no visible connection to navigable waterways, even if the gravel pit provides habitat for migratory birds. In Solid Waste Agency of Northern Cook County v. Army Corps of Engineers, the US Supreme Court said no.

The Clean Water Act also governs private industry and imposes stringent standards on the discharge of pollutants into waterways and publicly owned sewage systems. The act created an effluent permit system known as the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System. To discharge any pollutants into navigable waters from a “point source” like a pipe, ditch, ship, or container, a company must obtain a certification that it meets specified standards, which are continually being tightened. For example, until 1983, industry had to use the “best practicable technology” currently available, but after July 1, 1984, it had to use the “best available technology” economically achievable. Companies must limit certain kinds of “conventional pollutants” (such as suspended solids and acidity) by “best conventional control technology.”

Clean Air Act

The centerpiece of the legislative effort to clean the atmosphere is the Clean Air Act of 1970 (amended in 1975, 1977, and 1990). Under this act, the EPA has set two levels of National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS). The primary standards limit the ambient (i.e., circulating) pollution that affects human health; secondary standards limit pollution that affects animals, plants, and property. The heart of the Clean Air Act is the requirement that subject to EPA approval, the states implement the standards that the EPA establishes. The setting of these pollutant standards was coupled with directing the states to develop state implementation plans (SIPs), applicable to appropriate industrial sources in the state, in order to achieve these standards. The act was amended in 1977 and 1990 primarily to set new goals (dates) for achieving attainment of NAAQS since many areas of the country had failed to meet the deadlines.

Beyond the NAAQS, the EPA has established several specific standards to control different types of air pollution. One major type is pollution that mobile sources, mainly automobiles, emit. The EPA requires new cars to be equipped with catalytic converters and to use unleaded gasoline to eliminate the most noxious fumes and to keep them from escaping into the atmosphere. To minimize pollution from stationary sources, the EPA also imposes uniform standards on new industrial plants and those that have been substantially modernized. And to safeguard against emissions from older plants, states must promulgate and enforce SIPs.

The Clean Air Act is even more solicitous of air quality in certain parts of the nation, such as designated wilderness areas and national parks. For these areas, the EPA has set standards to prevent significant deterioration in order to keep the air as pristine and clear as it was centuries ago.

Toxic Waste

The EPA also worries about chemicals so toxic that the tiniest quantities could prove fatal or extremely hazardous to health. To control emission of substances like asbestos, beryllium, mercury, vinyl chloride, benzene, and arsenic, the EPA has established or proposed various National Emissions Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants. Concern over acid rain and other types of air pollution prompted Congress to add almost eight hundred pages of amendments to the Clean Air Act in 1990. (The original act was fifty pages long.) As a result of these amendments, the act was modernized in a manner that parallels other environmental laws. For instance, the amendments established a permit system that is modeled after the Clean Water Act. And the amendments provide for felony convictions for willful violations, similar to penalties incorporated into other statutes.

The amendments include certain defenses for industry. Most important, companies are protected from allegations that they are violating the law by showing that they were acting in accordance with a permit. In addition to this “permit shield,” the law also contains protection for workers who unintentionally violate the law while following their employers’ instructions.

Though pollution of the air by highly toxic substances like benzene or vinyl chloride may seem a problem removed from that of the ordinary person, we are all in fact polluters. Every year, the United States generates approximately 230 million tons of “trash”—about 4.6 pounds per person per day. Less than one-quarter of it is recycled; the rest is incinerated or buried in landfills. But many of the country’s landfills have been closed, either because they were full or because they were contaminating groundwater. Once groundwater is contaminated, it is extremely expensive and difficult to clean it up. In the 1965 Solid Waste Disposal Act and the 1970 Resource Recovery Act, Congress sought to regulate the discharge of garbage by encouraging waste management and recycling. Federal grants were available for research and training, but the major regulatory effort was expected to come from the states and municipalities.

But shocking news prompted Congress to get tough in 1976. The plight of homeowners near Love Canal in upstate New York became a major national story as the discovery of massive underground leaks of toxic chemicals buried during the previous quarter century led to evacuation of hundreds of homes. Next came the revelation that Kepone, an exceedingly toxic pesticide, had been dumped into the James River in Virginia, causing a major human health hazard and severe damage to fisheries in the James and downstream in the Chesapeake Bay. The rarely discussed industrial dumping of hazardous wastes now became an open controversy, and Congress responded in 1976 with the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) and the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) and in 1980 with the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA).

The RCRA expresses a “cradle-to-grave” philosophy: hazardous wastes must be regulated at every stage. The act gives the EPA power to govern their creation, storage, transport, treatment, and disposal. Any person or company that generates hazardous waste must obtain a permit (known as a “manifest”) either to store it on its own site or ship it to an EPA-approved treatment, storage, or disposal facility. No longer can hazardous substances simply be dumped at a convenient landfill. Owners and operators of such sites must show that they can pay for damage growing out of their operations, and even after the sites are closed to further dumping, they must set aside funds to monitor and maintain the sites safely.

This philosophy can be severe. In 1986, the Supreme Court ruled that bankruptcy is not a sufficient reason for a company to abandon toxic waste dumps if state regulations reasonably require protection in the interest of public health or safety. The practical effect of the ruling is that trustees of the bankrupt company must first devote assets to cleaning up a dump site, and only from remaining assets may they satisfy creditors. Another severity is RCRA’s imposition of criminal liability, including fines of up to $25,000 a day and one-year prison sentences, which can be extended beyond owners to individual employees.

The CERCLA, also known as the Superfund, gives the EPA emergency powers to respond to public health or environmental dangers from faulty hazardous waste disposal, currently estimated to occur at more than seventeen thousand sites around the country. The EPA can direct immediate removal of wastes presenting imminent danger (e.g., from train wrecks, oil spills, leaking barrels, and fires). Injuries can be sudden and devastating; in 1979, for example, when a freight train derailed in Florida, ninety thousand pounds of chlorine gas escaped from a punctured tank car, leaving 8 motorists dead and 183 others injured and forcing 3,500 residents within a 7-mile radius to be evacuated. The EPA may also carry out “planned removals” when the danger is substantial, even if immediate removal is not necessary.

The EPA prods owners who can be located to voluntarily clean up sites they have abandoned. But if the owners refuse, the EPA and the states will undertake the task, drawing on a federal trust fund financed mainly by taxes on the manufacture or import of certain chemicals and petroleum (the balance of the fund comes from general revenues). States must finance 10 percent of the cost of cleaning up private sites and 50 percent of the cost of cleaning up public facilities. The EPA and the states can then assess unwilling owners’ punitive damages up to triple the cleanup costs.

Cleanup requirements are especially controversial when applied to landowners who innocently purchased contaminated property. To deal with this problem, Congress enacted the Superfund Amendment and Reauthorization Act in 1986, which protects innocent landowners who—at the time of purchase—made an “appropriate inquiry” into the prior uses of the property. The act also requires companies to publicly disclose information about hazardous chemicals they use. We now turn to other laws regulating chemical hazards.

Chemical Hazards

Toxic Substances Control Act

Chemical substances that decades ago promised to improve the quality of life have lately shown their negative side—they have serious adverse side effects. For example, asbestos, in use for half a century, causes cancer and asbestosis, a debilitating lung disease, in workers who breathed in fibers decades ago. The result has been crippling disease and death and more than thirty thousand asbestos-related lawsuits filed nationwide. Other substances, such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and dioxin, have caused similar tragedy. Together, the devastating effects of chemicals led to enactment of the TSCA, designed to control the manufacture, processing, commercial distribution, use, and disposal of chemicals that pose unreasonable health or environmental risks. (The TSCA does not apply to pesticides, tobacco, nuclear materials, firearms and ammunition, food, food additives, drugs, and cosmetics—all are regulated by other federal laws.)

The TSCA gives the EPA authority to screen for health and environmental risks by requiring companies to notify the EPA ninety days before manufacturing or importing new chemicals. The EPA may demand that the companies test the substances before marketing them and may regulate them in a number of ways, such as requiring the manufacturer to label its products, to keep records on its manufacturing and disposal processes, and to document all significant adverse reactions in people exposed to the chemicals. The EPA also has authority to ban certain especially hazardous substances, and it has banned the further production of PCBs and many uses of asbestos.

Both industry groups and consumer groups have attacked the TSCA. Industry groups criticize the act because the enforcement mechanism requires mountainous paperwork and leads to widespread delay. Consumer groups complain because the EPA has been slow to act against numerous chemical substances. The debate continues.

Key Takeaways

Laws limiting the use of one’s property have been around for many years; common-law restraints (e.g., the law of nuisance) exist as causes of action against those who would use their property to adversely affect the life or health of others or the value of their neighbors’ property. Since the 1960s, extensive federal laws governing the environment have been enacted. These include laws governing air, water, and chemicals. Some laws include criminal penalties for noncompliance.

Exercises

- Who is responsible for funding CERCLA? That is, what is the source of funds for cleanups of hazardous waste?

- Why is it necessary to have criminal penalties for noncompliance with environmental laws?

- What is the role of states in setting standards for clean air and clean water?

- Which federal act sets up a “cradle-to-grave” system for handling waste?

- Why are federal environmental laws arguably necessary? Why not let the states exclusively govern in the area of environmental protection?

Cases

Clean Water Act

ENERGY CORP. v. RIVERKEEPER, INC., et al.

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

Argued December 2, 2008—Decided April 1, 2009

Justice Scalia delivered the opinion of the Court.

These cases concern a set of regulations adopted by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA or agency) under §316(b) of the Clean Water Act. Respondents—environmental groups and various States—challenged those regulations, and the Second Circuit set them aside. Riverkeeper, Inc. v. EPA, 475 F. 3d 83, 99–100 (2007). The issue for our decision is whether, as the Second Circuit held, the EPA is not permitted to use cost-benefit analysis in determining the content of regulations promulgated under §1326(b).

I

Petitioners operate—or represent those who operate—large powerplants. In the course of generating power, those plants also generate large amounts of heat. To cool their facilities, petitioners employ “cooling water intake structures” that extract water from nearby water sources. These structures pose various threats to the environment, chief among them the squashing against intake screens (elegantly called “impingement”) or suction into the cooling system (“entrainment”) of aquatic organisms that live in the affected water sources. See 69 Fed. Reg. 41586. Accordingly, the facilities are subject to regulation under the Clean Water Act, 33 U. S. C. §1251 et seq., which mandates:

“Any standard established pursuant to section 1311 of this title or section 1316 of this title and applicable to a point source shall require that the location, design, construction, and capacity of cooling water intake structures reflect the best technology available for minimizing adverse environmental impact.” §1326(b).

Sections 1311 and 1316, in turn, employ a variety of “best technology” standards to regulate the discharge of effluents into the Nation’s waters.

The §1326(b) regulations at issue here were promulgated by the EPA after nearly three decades in which the determination of the “best technology available for minimizing [cooling water intake structures’] adverse environmental impact” was made by permit-issuing authorities on a case-by-case basis, without benefit of a governing regulation. The EPA’s initial attempt at such a regulation came to nought when the Fourth Circuit determined that the agency had failed to adhere to the procedural requirements of the Administrative Procedure Act. …

In 1995, the EPA entered into a consent decree which, as subsequently amended, set a multiphase timetable for the EPA to promulgate regulations under §1326(b). Those rules require new facilities with water-intake flow greater than 10 million gallons per day to, among other things, restrict their inflow “to a level commensurate with that which can be attained by a closed-cycle recirculating cooling water system.” New facilities with water-intake flow between 2 million and 10 million gallons per day may alternatively comply by, among other things, reducing the volume and velocity of water removal to certain levels. And all facilities may alternatively comply by demonstrating, among other things, “that the technologies employed will reduce the level of adverse environmental impact … to a comparable level” to what would be achieved by using a closed-cycle cooling system. These regulations were upheld in large part by the Second Circuit ….

The EPA then adopted the so-called “Phase II” rules at issue here.[Footnote 3] 69 Fed. Reg. 41576. They apply to existing facilities that are point sources, whose primary activity is the generation and transmission (or sale for transmission) of electricity, and whose water-intake flow is more than 50 million gallons of water per day, at least 25 percent of which is used for cooling purposes. Ibid. Over 500 facilities, accounting for approximately 53 percent of the Nation’s electric-power generating capacity, fall within Phase II’s ambit. Those facilities remove on average more than 214 billion gallons of water per day, causing impingement and entrainment of over 3.4 billion aquatic organisms per year. 69 Fed. Reg. 41586.

To address those environmental impacts, the EPA set “national performance standards,” requiring Phase II facilities (with some exceptions) to reduce “impingement mortality for all life stages of fish and shellfish by 80 to 95 percent from the calculation baseline”; a subset of facilities must also reduce entrainment of such aquatic organisms by “60 to 90 percent from the calculation baseline.” Those targets are based on the environmental improvements achievable through deployment of a mix of remedial technologies, 69 Fed. Reg. 41599, which the EPA determined were “commercially available and economically practicable.”