1 Anthropology and the Ancient Greeks

Kendall House, PhD

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After completing this reading, you should be able to

- Discuss debates on the relation of anthropology to the Western intellectual tradition.

- Identify and discuss ways that anthropology has been influenced by ancient Greek thinking.

- Provide examples of durable themes in Western thinking that extend from Greek antecedents to the present.

CHAPTER Introduction

It is a great irony that while anthropology has primarily developed knowledge about ways of life and thought beyond the Western world, the theoretical frameworks developed by anthropologists remain centered on the Western tradition. Redoubling the irony, although anthropologists may be biased toward the study of European thinkers, histories of anthropology have tended to ignore ancient Greek and Roman thought. This book critically examines contemporary academic anthropology as a product of the Western intellectual tradition, while searching for resources and perspectives to broaden that vision. This chapter stresses the importance of situating Greco-Roman thought in a cosmopolitan, Eurasian ecumene that stretches from the Mediterranean to the Indian subcontinent, while making the case for attending closely to Greek influences on contemporary academic anthropology.

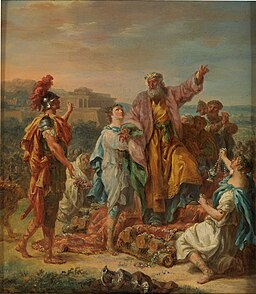

Vignette: AN ENCOUNTER IN KHANDAHAR, 326 BCE

In 326 BCE, there was an encounter between Alexander the Great, who built an empire larger than that of Rome, and an Indian spiritualist named Kalanos in what is today the province of Punjab, in east central Pakistan. Readers might be surprised to learn that in the time of Alexander the Great, the Hellenistic world swept eastward from the Mediterranean to the Himalayas, and included all of what is today Afghanistan. It can be somewhat disorienting to learn that Kandahar – an Afghan province where American troops were stationed during the first two decades of the 21st century – was invaded and conquered by Greek armies in 330 BCE. Renamed Bactria, the province was incorporated into the Hellenic world, and for three centuries it remained a zone of cultural interaction where Indian thought, Buddhism, and Greek philosophy blended (Goody, 1996). Indeed, Greek continued to be spoken even after Bactria was conquered by Kushan warriors from western China. But at the time of the meeting of Alexander and Kalanos, the cultural exchanges were only beginning.

The story of Alexander and Kalanos has its source in the works of Plutarch, a Roman philosopher who wrote a history of Alexander’s exploits around AD 100. Plutarch had relatively little to say about Kalanos. His discussion amounts to a single paragraph in The Life of Alexander (Thayer, 2007). But Plutarch’s brevity has not deterred later enthusiasts – who often hail from India – from developing richer accounts that share key themes.

On making contact, it is said, Alexander commanded wise men from the lands he conquered to appear before him and demonstrate the scope of their knowledge. He asked difficult questions, and failing convincing answers, ordered them executed. Kalanos was called after Alexander’s armies subdued the Punjab. The story thus seems to herald scenes of defeat and debasement in the face of superior Greek armies. But these are not the themes stressed in contemporary narratives (a Google search brought up 3.5 million returns).

To the contrary, current narratives offer a different lesson: Alexander’s military superiority did not endow him with greater wisdom or courage than Kalanos. Indeed, despite having been tutored by the great philosopher Aristotle, Alexander was outmatched. It is said that Kalanos refused to meet with Alexander until Alexander stripped himself naked, and refused to accept Alexander’s gifts. And he boldly questioned Alexander’s imperial strategy, stressing the risks of overstretching his empire.

Taken aback by his boldness, one of Alexander’s generals challenged Kalanos: “Alexander has conquered the world – what have you accomplished?” Kalanos replied: “I have conquered the desire to conquer the world.” Plutarch remarks, and contemporary accounts agree, that Kalanos went to his death with great courage, climbing onto a funeral pyre where he was burned alive, showing neither fear nor agony as the flames enveloped his body.

There is a growing scholarly literature on the interaction between Hellenic (Greek) and South Asian (Indian) thinking, as well as new interpretations of the relationship of Alexander and Kalanos (Stoneman, 2019). Gananath Obeyesekere, a South Asian anthropologist, has recently raised an interesting question (Obeyesekere, 2002). Observing that many cultures, from Native North America to West Africa have worldviews that assume reincarnation, Obeyesekere asks: What would anthropology look like if the field was founded by thinkers who took reincarnation for granted? For one thing, we might have noted how frequent themes of reincarnation are across cultures and our understanding of many local traditions on multiple continents might be very different.

ANTHROPOLOGY SANS ARISTOTLE?

Decisions about where to begin historical narratives are always somewhat arbitrary, but the choices we make can be consequential, and they ought to be transparent. The risk of getting history wrong might seem trivial, but to the degree that our understanding of the past shapes our capacity to explain the present and work on the future, it is important to seek good choices, and in all cases to explain the choices we have made. Which is another way of saying that beginning with ancient Greece can be problematic, as well as helpful.

We might begin by noting that anthropologists tend to minimize Greek influences. This is likely because most anthropologists feel that the narrative of Western civilization is problematic, in part because it is inward facing and self-congratulatory (Wolf, 1982). The very idea of a Western tradition is based on the proposition that Western thought is a separate and singular tradition, often combined with the proposal that Western thinkers produced the modern world while thinkers elsewhere were mere spectators (Pandian, 1985; Patterson, 1997).

This troubles anthropologists, because one of the signal contributions of anthropology during the 20th century was demonstrating the interconnectedness of the cultures of the world, the ubiquity of cross-cultural diffusion and acculturation, and the global sources of innovation and change.

Consider one example. In 1937, as fascist movements gained strength in Europe and nativist sentiments surged in the United States, a cultural anthropologist named Ralph Linton published a widely cited essay in The American Mercury (Linton, 1937). The title was “One-hundred percent American” and it was intended to be ironic. At the time “one-hundred percent American” was a popular political slogan among American nativists, favored especially by the Ku Klux Klan (Pegram, 2011). In two short pages Linton made quick work of any notion that American culture stood apart from the larger world or had Nordic foundations. To proponents of xenophobic efforts to keep “insidious foreign ideas” out of American civilization, Linton brought bad news: American culture was built from a melange of insidious foreign ideas and practices. Even speaking English was problematic, given that words of foreign origin outnumber those of English provenance. Indeed, English is one of the most thoroughly mixed languages on the planet.

Starting from an assumption that there is a Western tradition that begins in ancient Greece and flows continuously to the present, distinctive and separate from the world beyond, ignores the reciprocal influence of the East on the West and the West on the East in the ancient and medieval world (Goody, 1996). This applies not just to India and the Hellenistic ecumene, but equally to the critical role played by Arab thinkers in conserving Greco-Roman learning and transmitting it to the post-medieval west. There are, to this day, surprisingly few essays on the topic of “How Muslims Saved Western Civilization” (Glaser, 2010). Henri Pirenne’s thesis that “Charlemagne, without Muhammad, would be inconceivable” (Pirenne, 1927) is often overlooked. But anyone with awareness of the importance of the prefix Al- in algebra and algorithms or even Arabic numerals should need little persuasion. Anthropologists, for our part, are still insufficiently familiar with the works of Ibn Khaldun (Pisev, 2019).

Alongside ignoring reciprocal influences, there is a tendency toward over-attribution: a propensity to attribute everything to ancient Greece. Typical inventories include philosophy, logic, geometry, democracy, and perhaps science in general, and specific fields of knowledge. More marginally, it has been claimed that robots have Greek origins (Mayor, 2018). After the ancient Greeks, it seems, everything else is a footnote. But even if we set aside the claim that robots are a Greek invention, many of these claims are doubtful. Long ago, John Dewey challenged the idea that modern evidence-driven science has Greek origins (Dewey, 1988 [1929]), a critique later supported by classical scholars (e.g., Vlastos, 1975). More recently, the anthropologist Jack Goody persuasively argued that logic has much broader Eurasian roots (Goody, 1996). As for democracy, from a broader ethnological perspective, participatory, consensus building political processes appear to be less the invention of city states than their victim (Clastres, 1987).

But allowing for all of these reasons to start elsewhere, I am going to start from the premise that the impact of ancient Greece on the history of anthropology deserves study and reflection.

HOW “THE GREEKS” MIGHT MATTER

Contemporary anthropologists should take a lesson from Linton in their approach to both Western and non-Western traditions. And developing an appreciation for the cosmopolitan mixing of ideas is one reason why the ancient roots of anthropology should not be ignored, including ancient Greece. This raises questions about how and why some cultural ideas persist. In the 1980s, Richard Dawkins and other evolutionary scientists took up the problem of how ideas spread and mutate, and why some ideas become more influential and more durable than others (Dawkins, 1982).

Dawkins’ proposal was to add the concept of memes as cultural units equivalent to genes. This is an interesting but challenging idea, because although genes are quite complex to define, the underlying foundations of inheritance – DNA and RNA – are well understood. Ideas – might be expressed in musical compositions or performances, or in dance moves, or in paintings, or concepts of relatedness, or as tools, and tools take myriad forms, ranging from simple stone hammers to complex devices made of multiple materials and hundreds of parts that require coordinating the efforts of thousands of people to produce. It is difficult to see a genuine similarity between genes and whatever we might wish to call memes.

The sociologist Randall Collins proposed a different approach, analyzing the networks of thinkers whose ideas somehow ended up at the core of various intellectual traditions, where they have been conveyed to thousands and sometimes millions of students. Collins goes beyond the Western tradition to examine the sociology of intellectual traditions in India, China, and Japan. In all cases, he finds that prominent traditions tend to center on small numbers of scholars, and relations between intellectual ancestors and their descendants are simpler and more direct than might be expected. Collins finds six core principles associated with intellectual creativity: they involve personal contacts, develop through opposed ideas, have centers and margins, remain small (there are three to six “schools of thought” at any one time), perish without institutional support, persist through good times and bad, and are paradoxically driven to change when conservative thinkers attempt to resist change. That last point deserves clarification: conservative efforts to preserve intellectual traditions often bring more fundamental change to those traditions than do the efforts of progressives to introduce change (Collins, 2000: 379-383).

Thinking about how we come to learn what we do, and where those ideas come from – including anthropological ideas – is called reflexivity. Reflexive thought is important, but it can also generate inertia. Sometimes we have to proceed like pharmacologists, who only rarely can explain how specific drugs produce the effects that they do. Similarly, although we cannot explain why certain ideas developed, we can find traces of those ideas and identify probable relationships among the thinkers associated with them. In addressing this basic issue of where ideas come from and why they change, I am going to rely on two rather traditional and simple ideas long used by intellectual historians: the concept of culture as ballast, and the idea of living scholarly traditions.

Culture as Ballast

The concept of culture as ballast was articulated by an anthropologist named Aram Yengoyan, who attributed the concept to Alfred Kroeber, who was one of his professors (Yengoyan, 1986). In engineering, ballast refers to any material that increases stability, such as aggregate mixtures of gravels in road beds, or weights positioned in a ship to keep the center of gravity stable. Yengoyan was interested in intellectual ballast. As Yengoyan uses it, intellectual ballast refers to durable assumptions that participants in cultural traditions do not question or even consciously recognize. Ideas that act as ballast are durable and resistant to change. In effect, all that people need to do to keep things the way they are is to continue doing what they have “always” done. Returning to our previous point – the reason why intellectual conservatism is often so radical is that it emerges into view when traditions become visible and open to question. In examining the history of anthropology, we are interested in both conservation and change. Alongside noting new ideas, we will also encounter strikingly familiar ideas that we assume have recent origins but in fact are hundreds or thousands of years old. How have these ideas persisted?

Living Scholarly Traditions

There is another conventional approach to thinking about how old ideas persist in contemporary anthropology, and that is through living traditions and direct instruction. Randall Collins, as we noted above, stresses the importance of personal contact between teachers and students. To illustrate how this can matter, we will examine the thinking of a social anthropologist named Clyde Kluckhohn, who presented a series of lectures on the classical roots of anthropology to an audience of classicists (Kluckhohn, 1961). It required considerable courage, as classicists are scholars who specialize in reading the works of ancient Greco-Roman thinkers in the original language.

Kluckhohn remarked that by 1960, few of his colleagues retained an interest in classical scholarship, and very few achieved reading fluency in Greek or Latin. Indeed, by 1960 there was a social division between classical studies of Greece and Rome and anthropology. Classical archaeology, for example, is the study of the material remains of literate civilizations, while anthropological archaeology is the study of prehistoric traditions (defined as peoples without written traditions). The two fields had their own departments, and rarely the twain did meet. The division persists, though much has since changed (Humphreys, 1978; Redfield, 1991).

But Kluckhohn noted that among earlier generations of anthropologists this was not true. Not all early researchers had extensive academic training, but among those who did, a large share of their educational effort was invested in learning to read Greek and Latin texts for the purpose of studying the classics. Karl Marx, for instance, may be much better known for co-authoring the Communist Manifesto in 1848, but he began his scholarly work with a dissertation on the atomic theories of Democritus and Epicurus (Burns, 2000). Marx’s dissertation would have been impossible without literacy in Latin and archaic Greek. Given this shift in academic training, Kluckhohn noted, contemporary anthropologists might underestimate the importance of the classical humanities in the history of anthropological thinking: Aristotle, Plato, Cicero, and other classical authors might be much more important to how we think now than we might think.

Certainly it is the case that in England at least classically trained scholars remained prominent in anthropology well into the 20th century. Consider leading social anthropologists who took their degrees in classics, including Sir James Frazer (1854-1941) and Robert Marett (1866-1943). There are also strong links between Greek thinking and German philosophers, a relationship that developed during the Enlightenment and persists to the present. The post-Enlightenment German philosophical tradition powerfully impacted the history of anthropology, and from early figures like G.W.F. Hegel (1770-1831) to 20th century giants like Martin Heidegger (1889-1976) and Hans-Georg Gadamer (1900-2002), many German thinkers have developed their philosophies in dialogue with ancient Greek writers (Butler, 1935).

Durable Themes from Ancient Thinkers

A number of anthropologists have identified durable themes in ancient Greek thought which continue to be expressed in contemporary anthropology. In presenting a few of these themes, questions about whether their persistence is a product of ballast or a living tradition will be set aside because they cannot be answered here. Additionally, rather than emphasizing particular thinkers, I am going to focus on themes that other historians of anthropology and / or classical scholars have described.

Dualism and Monism

Murray Leaf wrote one of the first histories of anthropology that explored broader intellectual currents beyond and before anthropology emerged as an academic discipline (Leaf, 1979). One question whose history Leaf explored was epistemological: What kind of knowledge can or should anthropologists pursue? Leaf proposed that ever since the Greeks there have been two contending answers : monism and dualism. For Monists, the world that we share together through our senses and express in language is the only world that exists, whereas for Dualists there is a hidden realm beyond our awareness and ability to articulate that causes us to behave in the manner that we do.

In contemporary anthropology, Leaf argues, many thinkers continue to express these opposed epistemologies. For dualists, anthropology is a science that seeks to identify hidden forces that shape human behavior. Accordingly, they develop theories and methods that generate data beyond the ken of the people they study. In contrast, anthropologists who embrace monism stress that humans live in worlds of perceptible, shared ideas. Anthropology is not about the world as it is, but rather the world as it is imagined. The aim of anthropology is to expand our collective understanding of how humans have imagined their worlds.

The important point that Leaf was making is that contemporary anthropologists – largely without realizing it – were still engaging in debates that were over two thousand years old.

Etic and Emic

To my knowledge, there are no schools of modern anthropologists who describe themselves as either dualists or monists (the opposition is important in Marxist thought, but it has a different meaning there). But Leaf’s distinction between monism and dualism has much in common with another pair of opposing terms that were frequently used to sort out approaches to anthropology up until 1980: emic versus etic knowledge. As it is generally used among cultural anthropologists, the word emic refers to knowledge the people we study can share with us. Emic knowledge not only can but has to be taught to the ethnographer who studies a different social group. In contrast, etic knowledge refers to data known only by the scientific inquirer: people without scientific training will not know that it exists, and talking to people will usually not be helpful.

For example, unless the people you work with have been taught about cholesterol levels, it will not be helpful for a medical anthropologist to ask people about the ratio between HDL (high density lipids) and LDL (low density lipids). It will be much more effective to take a blood draw and perform a laboratory test. The results can then be explained to patients – whose expertise gives way to science.

As you might be gathering, finding relationships among concepts and ideas is a slippery business, because ideas are mercurial. This is part of what makes studying the history of ideas interesting. Consider, for example, yet another opposition that is similar to monism and dualism but is part of the worldview of Balinese Hindus, whose ontology divides existence into Sekala – the perceptible world – and Niskala – the hidden world that shapes what we experience (Eiseman, 2009). Given a thousand years of interaction between Greece and India, this parallel need not surprise us.

Nature, Culture, and Primitivism: Lessons from the Classics

If Leaf’s inquiry into the expression of ancient Greek thinking in contemporary anthropological thought was unusual in 1979, it is less so now. The cultural anthropologist Marshall Sahlins, for example, argued that there is a durable Western idea of human nature that is both singular and illusory and has caused much mischief in European political history (Sahlins, 2008). And intellectual historians outside of anthropology have argued that contemporary problems – like racism – also have deep roots in ancient Greek thought (Isaac, 2013; Jahoda, 2018).

In concluding this chapter, we will examine ancient ideas of obvious relevance to later anthropology which indeed serve as ballast in the history of the field. Importantly, they are the work of classical scholars.

Lessons from Classical Scholars

In his lectures on anthropology and the classics, Kluckhohn raised an important point: examining ancient and medieval writings to gain insights into ancient thought is difficult and time consuming, and few anthropologists today are prepared to do it. As a result, the work of translation and interpretation falls largely to scholars known as classicists or classical humanists who invest enormous time and effort into working with ancient texts in the original language. They often produce work of great relevance to the history of anthropology, without much awareness that this is the case.

Consider the work of Arthur Lovejoy and his student George Boas in the early 20th century. In developing their study on Primitivism and Related Ideas in Antiquity (Lovejoy and Boas, 1935), Lovejoy and Boas invested many years carefully reading the entire archive of ancient Greek and Roman texts from Thales to Cicero – in archaic Greek and Latin! They planned to ultimately produce a four volume work, but were only able to collaborate fully on the first volume (Boas later published a work on primitivism in patristic thought during the Middle Ages; see Boas, 1948).

Their method of inquiry is worth noting. As they worked, they identified fundamental themes related to their topic, and translated passages expressing those themes into English, organizing them into a descriptive text that included both the Greek or Latin original and an English translation. This enabled scholars with a command of archaic Greek and Latin to check their translations.

In identifying themes and organizing their material, Lovejoy and Boas sought to produce an analysis that was heavily grounded in the original sources. They allow themselves merely 20 pages to interpret, define, and discuss their conceptual framework, dedicating 400 pages to source translations. The methods they used were not all that different from contemporary social researchers who embrace approaches called grounded theory. The goal is to capture emergent themes and organize them through coding (Glaser and Strauss, 1968).

Did Lovejoy and Boas learn anything useful?

From their own remarks, the central finding of their work was that many ideas widely believed to be modern – developed since 1750 – were in fact developed by thinkers in ancient Greece. From the perspective of contemporary anthropologists, their discussion of deep themes related to nature, culture, and primitivism is inherently interesting.

Culture : Nature :: Nomos : Physis

In the middle of the 20th century, a French anthropologist named Claude Levi-Strauss – who had a deep interest in thought and language – developed a shorthand for expressing opposing ideas. The subtitle above reads as follows:

Culture [is to] Nature [as] Nomos [is to] Physis

The statement above asserts that the opposition between the Greek concepts of nomos and physis is equivalent to the opposition between the Latin concepts of culture and nature. This is an important claim, because the word culture – arguably the central concept of 20th century anthropology – has Latin rather than Greek roots, yet many of the meanings it carries have Greek roots.

We will start, however, by examining the Latin (Roman) roots of the idea of culture, drawing heavily on the work of Raymond Williams (Williams, 1976).

The word culture derives from the Latin word colore. Its deepest sense is captured by agricola, which initially refers to a farmer or peasant – someone who cultivates. This root reaches into its most fundamental English cognates: agriculture and cultivation. To cultivate is to modify the world through human action, by bringing an area into agricultural use. Shortly before the start of the Christian era, Cicero (106 – 43 BC) metaphorically expanded the meaning to include cultura animi – the cultivation of the soul. Thus, before the common era, the root meaning of culture included modifying both the world around us and our inner selves, leading a strong connection to later emerge between cultivation and education.

Colore is also related to cultus – as in a religious cult – but more poignantly as engaging in worship, and also to colonia – initially meaning “to inhabit”, but later expanded to include “to colonize”). , but brings its full meaning in the contemporary English words. The core idea of culture is modifying the world through human action.

But to fully understand colore and its importance for the modern word culture – which only came into use in German and English as culture around 1750 (the Germans later changed the spelling to Kultur) – we have to return to the Greek terms, nomos and physis, and especially the latter, because physis helps us understand nature. As Raymond Williams noted, nature and culture as words emerge together in intricate relationships. You cannot grasp one without the other.

In Latin, nature is the absence of culture. In the Germanic languages, it is wildness, wilderness. In both cases, in an intricate inversion of culture, the natural world does what it does without human intervention; it is a world unmodified by human action, existing independently of our understanding. Like culture, the natural is both within us – part of our nature as human beings – as well as beyond us in the world around us. If we are told “just do what comes natural” that means we need no instruction; education is superfluous.

But in Greek usage, physis as nature also carries a normative meaning (Lovejoy and Boas,1935: 103-116). This moral, normative sense persists into contemporary English usages: the natural is good, correct, proper; there is something deeply wrong with acts that go against nature; they are unnatural. As an illustration, consider that for many years, from the early 19th century forward, certain sexual relations were criminalized as crimes against nature, which included same sex relationships as well as prostitution, rape, incest, bestiality, and sexual abuse of minors (Wikipedia, Crimes Against Nature). Because the concept of the natural connects a powerful moral vision to an understanding of what is innate, permanent, and unchanging, a great deal of critical work in the humanities and social sciences has endeavored to denaturalize categories that are defined as natural in Western societies.

Nomos stands in opposition to physis – referring by contrast to that which is learned, acquired, and requires instruction. Just so, it is that which is open to human manipulation and construction. We can make of nomos what we want. Importantly, for varied ancient thinkers, both the natural and the cultural can be good or bad, but the terms are polarized: if culture is positive, then nature is negative.

These oppositions and their meanings have percolated across the centuries, and they are still very much with us. Which one we choose to celebrate waxes and wanes. In the 1950s, Americans embraced highly processed foods, including Jello, Velveeta, margarine, and hot dogs, not to mention artificial milk, which was considered healthier than breast milk for infants. The more artificial the food, the more processed, the less recognizable, the better. By the 1970s, a shift had occurred toward foods that were advertised as “one hundred percent natural”, “nothing artificial added” with “ingredients you can see and pronounce.” We can point to broader shifts as well. For example, today, rather than celebrating the “conquest of nature” there is a strong sense that human dominated ecosystems are producing disasters of epic proportions. American culture thus shifted in the space of a generation from a celebration of culture to celebrating nature.

Cultural and Chronological Primitivism

In presenting their core findings, Lovejoy and Boas introduce two key concepts in ancient thought. Cultural primitivism, as Lovejoy and Boas define it, refers to “the discontent of the civilized with civilization” (Lovejoy and Boas, 1935:7). It is a celebration of living on the margins of civilization. Primitivism involves a longing for oneness with nature, a life that is simpler, and stripped of artifice and the artificial. In the ancient Greek world, getting back to nature would be recognizable to many in the West today, as it included forgoing luxury and the pursuit of wealth and influence, and often embracing vegetarianism.

Their second concept, chronological primitivism, introduces a temporal dimension to achieving a return to the primitive, which might be a past that is better or worse than the present, but very often there was a doctrine of decline and degeneration: the progressive weakening of human beings, and the progressive corruption of human societies. The future, likewise, could promise either an escape from nature or a return to nature, and a return to paradise or the end of the natural world.

There is much more to be said here – and we will return to these topics in later chapters – but the fundamental point remains that made by Murray Leaf: many of the most important concepts in contemporary anthropology, and many of the most deeply contested debates, are constructed and fought out on conceptual frameworks that have very deep histories. In learning more about that history we can become more aware of it, including its complex origins and development. And in becoming more aware of these deep assumptions we can discover the potential to think beyond them.

The Ancient Lexicon of Prejudice: Barbarians and Monsters

Western anthropologists inherited concepts with Greco-Roman roots that extend back to the time of Aristotle and the imperial expansion of Alexander the Great. In the Hellenic world, the category of Barbaroi provided a sweeping, all purpose insult that included all peoples beyond the Greek ecumene (Gillett, 2013). During the era of the Roman empire, it was applied broadly to peoples on the northern periphery, including the Germanic tribes. It carried a powerful pejorative sense, being an onomatopoeic imitation of “the gibberish sound of non-Greek languages.”

But peoples on the margins of the Hellenic and Roman worlds were not always despised. There was also a celebration of “happy lands, far, far, away” and peoples uncorrupted by urban life.

Similarly, the “isles of the blessed” were on the margins of the world – essentially corresponding to the Judeo-Christian concept of heaven – but there were also expectations of monsters on the fringes of the ancient world. Monsters were widely accepted since the time of Pliny the Elder, whose natural history described human-like beings who differed in disturbing ways from more proximate peoples. Some had heads that were in their chest rather than on their shoulders, others carried their heads around in their arms. Some had feet that pointed the opposite direction of their eyes. A great many mixed human and animal qualities and bodies.

EXCLUDED ANCESTORS? SUMMARY AND CLOSING QUESTIONS

This chapter introduced ancient sources of modern, Western, academic anthropology. It focused on Greco-Roman influences while arguing for a larger perspective that recognizes intellectual interactions that brought ideas from South Asia, Mesopotamia, and the Mediterranean together. It introduces the concepts of cultural ballast and living scholarly traditions to explain how ideas that are two thousand years old can remain influential. To introduce the premise that ancient ideas can have a durable influence, oppositions between dualism and monism, are discussed, as well as the ancient roots of the opposition between nature and culture, which is foundational to modern anthropology.

The question arises: How might such a history contribute to a more inclusive anthropology? Or does it stay too close to traditional histories and end up centering anthropology on the Western tradition? These questions prompt several observations, but cannot be fully answered.

It remains the case that resources for writing inclusive histories of the ancient world remain underdeveloped. Anthony Pagden argues that at present, histories of fields like anthropology remain “inescapably Eurocentric” (Pagden, 1995: 5). It is important to continue to develop new perspectives, and recognizing the need for a more cosmopolitan and global vision is the first step to achieving that goal.

At the same time, the degree to which Greco-Roman ideas like nature and culture find expression in modern anthropology are instructive and demonstrate the degree to which ideas can indeed act as cultural ballast.

Additional Resources ON ANTHROPOLOGY AND THE CLASSICS

The readings and resources below are provided as optional sources if you have an interest in following up some of the content discussed. When possible, sources listed are accessible as Open Educational Resources.

Arora, Surbhi. 2022. “Ancient India and Ancient Greece: An Exploration of the Historical Connections.” Diplomatist.

Glaser, Linda. 2010. “Expert: Muslims — and Astrology — Saved Civilization, in Cooperation with Jews and Christians.” Cornell Chronicle, April 19.

Goody, Jack. 1996. Food and Love: A Cultural History of East and West. Verso.

Anonymous. 2023. Mythical Creatures. Digital Maps of the Ancient World. Website.

Pemberton, Harrison J. 2021. The Buddha Meets Socrates: A Philosopher’s Journal. Rabsel Editions.

Sahlins, Marshall. 2004. Apologies to Thucydides: Understanding History as Culture and Vice Versa. University of Chicago Press.

Sen, Amartya. 1997. “Indian Traditions and the Western Imagination.” Daedalus 126 (2): 1–26.

Thayer, Williams. 2007. “Plutarch, the Parallel Lives.” The Life of Alexander. Web page. University of Chicago.

References Cited: Chapter 1

Boas, George. 1948. Primitivism and Related Ideas in the Middle Ages. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Burns, Tony. 2000. “Materialism in Ancient Greek Philosophy and in the Writings of the Young Marx.” Historical Materialism 7 (1): 3–39.

Butler, Eliza Marian. 1935. The Tyranny of Greece Over Germany: A Study of the Influence Exercised by Greek Art and Poetry Over the Great German Writers of the Eighteenth, Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Cambridge University Press.

Clastres, Pierre. 1987. Society Against the State: Essays in Political Anthropology. Zone Books.

Collins, Randall. 2000. The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change. Belknap Press.

Dawkins, Richard. 1982. The Extended Phenotype: The Long Reach of the Gene. Oxford University Press.

Dewey, John. 1988. [1929] The Quest for Certainty: A Study of the Relationship between Knowledge and Action. Allen and Unwin.

Eiseman, Fred B. 2009. Bali: Sekala & Niskala. Tuttle Publishing.

Gillett, Andrew. 2013. “Barbarians, Barbaroi.” In The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, edited by Roger Bagnall and Kai Brodersen, 1043–45. Blackwell.

Glaser, Linda. 2010. “Expert: Muslims — and Astrology — Saved Civilization, in Cooperation with Jews and Christians.” Cornell Chronicle, April 19.

Glaser, Barney G., and Anselm Strauss. 1968. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Goody, Jack. 1996. The East in the West. Cambridge University Press.

Humphreys, Sally. 1978. Anthropology and the Greeks. Routledge.

Isaac, Benjamin. 2013. The Invention of Racism in Classical Antiquity. Princeton University Press.

Jahoda, Gustav. 2018. Images of Savages: Ancient Roots of Modern Prejudice in Western Culture. Routledge.

Kluckhohn, Clyde. 1961. Anthropology and the Classics. Brown University Press.

Leaf, Murray J. 1979. Man, Mind, and Science: A History of Anthropology. Columbia University Press.

Linton, Ralph. 1937. “One-Hundred Percent American.” The American Mercury, 1937.

Lovejoy, Arthur and George Boas. 1997 [1935]. Primitivism and Related Ideas in Antiquity. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Malefijt, Annemarie de Waal. 1974. Images of Man: A History of Anthropological Thought. Knopf.

Mayor, Adrienne. 2018. Gods and Robots: Myths, Machines, and Ancient Dreams of Technology. Princeton University Press.

Obeyesekere, Gananath. 2002. Imagining Karma: Ethical Transformation in Amerindian, Buddhist, and Greek Rebirth. University of California Press.

Pagden, Anthony. 1995. Lords of All the World: Ideologies of Empire in Spain, Britain and France 1500-1800. Yale University Press.

Pandian, Jacob. 1985. Anthropology and the Western Tradition: Toward an Authentic Anthropology. Waveland Press.

Patterson, Thomas C. 1997. Inventing Western Civilization. NYU Press.

Pegram, Thomas R. 2011. One Hundred Percent American: The Rebirth and Decline of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s. Ivan R. Dee.

Pirenne, Henri. 1969 [1927]. Medieval Cities. Frank Halsey, translator. Princeton University Press.

Pisev, Marko. 2019. “Anthropological Aspects of Ibn Khaldun’s Muqaddimah: A Critical Examination. Bérose – Encyclopédie internationale des histoires de l’anthropologie. Paris.

Redfield, James. 1991. “Classics and Anthropology.” Arion: A Journal of Humanities and the Classics 1(2): 5–23.

Sahlins, Marshall David. 2008. The Western illusion of human nature. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press.

Stoneman, Richard. 2019. The Greek Experience of India: From Alexander to the Indo-Greeks. Princeton University Press.

Thayer, Williams. 2007. “Plutarch, the Parallel Lives.” The Life of Alexander. Web page. University of Chicago.

Vlastos, Gregory. 1975. Plato’s Universe. University of Washington Press.

Williams, Raymond. 1976. Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society. Oxford University Press.

Wolf, Eric. 1982. Europe and the People Without History. University of California Press.

Yengoyan, Aram. A. 1986. Theory in Anthropology: On the Demise of the Concept of Culture. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 28(2), 368–374.

Media Attributions

- La_mort_de_Calamus_-_Beaufort