6 A Generation of Materialists: Anthropology in the Long Decade of the 1860s

Kendall House, PhD

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After completing this reading, you should be able to

- Identify, describe, and discuss key themes and keywords in 19th century anthropology.

- Identify, describe and discuss central debates in 19th century anthropology.

- Discuss and explain the significance of the Long Decade of the 1860s

- Identify and discuss new efforts to include excluded ancestors who worked during the 19th century.

Introduction: A GENERATION OF MATERIALISTS

Anthropology has many beginnings. Some histories start with Antiquity, others the Renaissance, and yet others the Enlightenment. Perhaps better put, anthropology has been reinvented multiple times. And to narrate that history, we also need to be willing to make new starts. This chapter examines the reinvention of anthropological thinking during the 19th century, with a particular focus on a magical decade when prior developments coalesced and the stage was set for the next half-century: the long 1860s.

This chapter introduces keywords, core themes, and fundamental debates that are widely used to interpret 19th century anthropology. After touring the colonial world, we will examine the work of a canonical thinker – Lewis Henry Morgan – whose key works conveniently capture the full sweep of 19th century anthropology, raising important questions about excluded ancestors along the way. This chapter will focus on Anglophone anthropology in the United States and Great Britain,

Anglophone Anthropology

In prior chapters we have selectively highlighted the contributions of Spanish, French, and German anthropologists. In this chapter we will focus on English-speaking or Anglophone anthropology, particularly in the United States. By the end of the 19th century, English was emerging as the international language of anthropology, its importance reflecting the sheer scale of the British empire (which we will discuss shortly).

We will also examine the institutional maturation of American anthropology and the emergence of antecedents of the four subfields: physical anthropology, historical linguistics, social anthropology, and archaeology, and the development of methods.

But first, let’s try to answer a very basic question.

When was the 19th Century?

Centuries are typically laid out from even to odd digits: 1800 to 1899, for example. And that span offers a straightforward answer to our question. But historians are more interested in units of time that map notable periods of coherence, or moments of change. Eric Hobsbawn, for example, framed his work on the history of modern capitalist systems as “the long 19th century.” For Hobsbawn, the 19th century spanned 125 years, from the French Revolution in 1789, and to the start of the First World War in 1914 (Herman and Hobsbawn, 2012). Other historians have adopted similar concepts (Blackbourn, 2012). The “long century” concept works for the history of British anthropology, where the 19th century lingered until 1922.

Other historians adopt a short chronology. Histories of England, for example, often focus on the Victorian Age – the period when Queen Victoria was enthroned, from 1837 to 1901. And the best synthetic history of 19th century anthropology, George Stocking Jr.’s Victorian Anthropology, loosely adopts this short chronology, selecting 1880 as the end of the century (Stocking, 1987). But arguably, Stocking was less interested in start and end points than the middle decade of the 1860s.

The Long Decade of the 1860s

Following Stocking’s lead, I am going to focus less on the beginning and ending than the midpoint. This approach to the 19th century was first taken by the anthropologist Alfred Kroeber (Kroeber, 1952). More recently is has been championed by Thomas Trautmann and his colleagues (e.g., Shryock, Trautmann, and Gamble, 2011). The widely accepted mid-point is not exactly dead center, but it comes close: the “long decade of the 1860s” starts in 1859 and ends in 1871. Those dates may be familiar to you if you have read the works of Charles Darwin. The Origin of Species was published in 1859, and The Descent of Man in 1871. The long decade was, thus, the Decade of Darwin. But in fact, as we will see in this chapter, a great deal more was going on during this long decade than Darwin’s revolutionary ideas.

For one thing, it was in 1859, as Trautmann and colleagues remind us, that unassailable evidence of the antiquity of humanity was discovered and archaeologists began correlating evidence for human activity with geological stratigraphy. Although the concept of prehistory had been invented earlier in Scandinavia, it was in the 1860s that the idea of archaeology as a natural history of humanity prior to written texts took hold. After 1859 it was necessary to go deeper than a short chronology respectful of the Bible and explore Deep Time. Currently, accepted evidence for the existence of hominins extends more than six million years into the past, while the origin of the universe is widely agreed to require some 12 billion years. Numbers like that were unthinkable prior to the 1860s.

The 1860s was also the decade when Marx published the first volume of Das Kapital, and the American Civil War was fought, leading to a ban on slavery – but not forced labor – in the English-speaking world. And as Stocking and Kroeber argued, the long decade of the 1860’s marks a time of convergence, when 19th century anthropology gelled (Kroeber 1950; Stocking, 1987:45).

Keywords in 19th Century Anthropology

There is no unifying label for 19th century thought analogous to the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, or the Romantic movement. But if we focus only on anthropology, we can identify key words that are widely used in interpretations of the 19th century. No label has been more frequently used than unilinear evolutionism (also referred to as unilineal evolutionism).

In either spelling, the first term translates as one line. Evolutionism – in its 19th century, meant progress. To evolve is to improve. Thus unilineal evolutionism argues that there has been one line of progress: human history exhibits a universal pattern of development.

You won’t be surprised, at this point in the course, to learn that no 19th century anthropological thinker actually held such a simple model, nor that many flatly opposed it. Neither will you be surprised to learn that no writer in the 19th century described their work as unilinear evolutionism. Like the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, and Romanticism, these labels were invented later by intellectual historians. And as is often the case, it is difficult to determine exactly when and where that invention occurred.

Fortunately, today we have powerful search tools like Google Ngram (see Resources at the end of this chapter). While it is not perfect, Google’s Ngram scans millions of books in seconds, and reports any matches. No human scholar can match it. Using Ngram, we can say that unilineal evolutionism was first used in print by a German-American anthropologist named Robert Lowie in 1920 in his book Social Organization (Lowie, 1920: 303). The context was a critique of the ideas of 19th century thinkers, a few of whom we will have time to introduce in this chapter (especially Lewis Henry Morgan). The label unilineal evolutionism then disappeared for several decades – during which time unilineal was more commonly used as a name for a kind of kinship system called unilineal descent. Perhaps to avoid confusion, Lowie himself switched to unilinear evolutionism a few years later (Lowie, 1924: 167). Both labels fell into disuse in the 1950s, before making a comeback in the 1960s as part of a movement known as neo-evolutionism. Their highest usage, however, occurred between 1970 and the year 2000. This reflects their popularity in introductory surveys of anthropology and the history of anthropology (e.g., Barnard 2000; Harris, 2001).

The most important observation to note is that Google Ngram finds zero uses of either unilineal evolutionism or unilinear evolutionism prior to 1920.

Other keywords strongly associated with 19th century anthropological thinking include the doctrine of the psychic unity of mankind and the doctrine of independent invention. These ideas are related, and connected to nonlinear evolutionism. The existence of a universal pattern of development and the frequency of independent invention depend on the psychic unity of mankind: if the minds of all humans did not work in the same way, why would history follow a singular path, and why would we find similar objects, beliefs, or institutions among far flung societies as the result of independent invention rather than diffusion? But even diffusion – the outward spread of cultural innovations from center to periphery – assumes commonality in the ability to borrow and adapt across traditions.

Despite the importance of these doctrines in 19th century thinking, they are all retrospective interpretations: references to the doctrine of psychic unity only appear in print after 1900, and nearly all references to independent invention prior to 1900 concern patent disputes rather than anthropological debates.

Key Themes and Debates in 19th Century Anthropology

The process of reading historical writings, identifying themes, developing interpretations and weaving them into a synthetic narrative is fundamentally humanistic in nature. It requires a lot of intellectual effort. It is an art. The narrative synthesis I offer is not unique, but it does arrive at readings that differ from many conventional treatments. In this chapter, I will examine four themes that were prominent in 19th century anthropology: the quest for origins, the emergence of a generation of materialists; the dominance of an ideology of civilization that was stunningly arrogant; and the normalization of imperialism.

We will also introduce three fundamental debates anthropologists helped shape with ramifications far beyond anthropology: the woman question (which spiked in the decade of the 1860s, and again at the end of the century); the debate between monogenism and polygenism (which was really a debate over racial slavery); and – in the United States particularly – the Indian problem (which was really a contest between those favoring cultural assimilation and those favoring genocidal extermination of indigenous peoples). Nineteenth century anthropologists came down on both sides of these debates, and the arguments they developed were consequential.

THE COLONIAL WORLD ORDER IN THE 19th CENTURY

By the close of the 19th century, the major national anthropological traditions that would dominate the 20th century – American, British, French, German, and Dutch – were well established, and each was following a distinctive path (Barth, Gingrich, Parkin, and Silverman, 2010). It is impossible to understand the centrality of these national traditions to the history of anthropology without an awareness of 19th century empire building. The growth of European and American anthropology in the 19th century was closely related to the expansion of European and American empires. Anthropology flourished as empires expanded.

By the close of the 19th century almost the entire non-western world was either colonized (e.g., sub Saharan Africa) or in a neo-colonial situation of dependency (e.g., Latin America). The most notable exception was Japan, which would seek its own empire late in the 19th century, dominating 20% of the world’s population by 1942.

No 19th century empire was as vast as the British empire. There was a saying that the sun never set on the British empire, and that held true. British colonies were strung around the globe, and included Canada (partially independent in 1867), Australia, South Asia (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Burma), and most of eastern Africa, from Egypt to South Africa. To this we must add Belize and British Guyana in the Americas, and holdings in the Caribbean, Indian Ocean, and Pacific islands. By 1900, the British empire encompassed one quarter of the land surface of the world – and was half again as large as the Soviet Union at its greatest extent. Today the remnants of that empire – the British Commonwealth – includes 24 member nations.

In relation to the prominence of English as a language of anthropology, to the British empire we must add the United States, which was also a majority English speaking nation. In addition to the “lower 48” sweeping from the Atlantic to the Pacific, in the 19th century the United States acquired Alaska from Russia, and claimed Hawaii, Puerto Rico, Cuba, and the Philippines in 1898. In addition, following the adoption of the Monroe Doctrine in 1823, American geopolitical interests loomed large over the entire western hemisphere, from Mexico to Chile.

French possessions were less expansive, but included most of West Africa, as well as Madagascar and Indochina (Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia), and some holdings in the Pacific. The most important Dutch colony was the East Indies (today known as Indonesia), along with Surinam in South America. The Germans came late to overseas colonies, but late in the century Germany acquired scattered African possessions – Togo, Cameroon, Tanganyika (Tanzania) and Southwest Africa (Namibia) – as well as northeastern New Guinea, and some holdings in the Pacific.

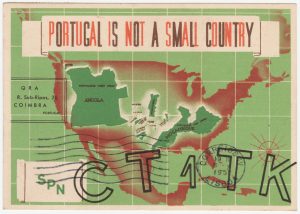

The list is not exhaustive. You might be surprised by the absence of Spain and Portugal, the first European imperial powers, who divided the globe between them in 1493. But after the Spanish American war, Spain’s possessions were limited to Morocco and the Spanish Sahara. Spain’s greatest influence was linguistic and religious, as Spanish continued to be the national language across the former Spanish colonies and Catholicism was the dominant faith.

Similarly, Portuguese continued as the national language in Brazil, despite independence in 1825. Across the Americas, revolutions was led by European immigrants, and national languages were those of the colonists rather than indigenous peoples. But unlike Spain, Portugal held firmly to its remnant colonies, fighting bloody wars to retain its African colonies – Angola and Mozambique – until 1975. Long after Portugal’s imperial moment ended, colonial possessions continued to play a large role in Portugal’s identity. But during the 19th century, Spanish and Portuguese anthropologists had relatively limited influence, and today anthropologists from other nations conduct most research in their former colonies. Similarly, despite the early importance of Siberia in the Enlightenment origin of anthropology, by the 19th century Russian research was marginalized. Lastly, we have overlooked Danish claims to Greenland, Belgium’s murderous exploitation of the Congo (Zaire), and Italian interests in Ethiopia. The story of European world domination is long and brutal.

Studying a map of European empires – available on Wikipedia – is essential for understanding anthropology, for several reasons. First, it brings home the fact that by the late 19th century there were almost no communities anywhere on the face of the globe where an anthropologist could conduct research that was not enabled or shaped by colonial domination. Anthropologists, almost without exception, were citizens of the major imperial powers, and the people they studied had been colonized and were governed by those imperial powers. Recognizing this helps us understand why colonial power dynamics were inescapable for most of the history of anthropology, and why discussions of decolonizing anthropology continue to be contentious in anthropology today (Gupta and Stoolman, 2022).

This will be evident throughout our discussion of 19th century anthropology, starting from a canonical figure: Lewis Henry Morgan.

VIGNETTE: MORGAN MEETS PARKER

The friendship between Lewis Henry Morgan (1818-1881) and Ely Samuel Parker (1828-1871) is one of the most famous and apocryphal tales in the history of American anthropology. It has been told and retold repeatedly by different authors, who have drawn varied lessons from it (Resek, 1960; Michaelsen, 1996; Deloria, 1998; Tooker, 2001; Trautmann, 2008). For our purposes, it introduces most of the themes and developments that we will examine in this chapter. There is thus no better place to start our study of 19th century anthropology. We will begin by introducing the key characters, followed by a brief rendering of the tale, before unraveling its complexity.

The Characters

Lewis Henry Morgan, a descendant of English colonists in upstate New York, would go on to become the most influential anthropologist in the United States, serving a term as President of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Morgan is credited with writing the first modern ethnography, inventing the study of kinship systems, and developing a theoretical framework that would dominate American anthropology through the end of the 19th century.

Ely Parker hailed from an influential Tonawanda Seneca family. Partly as a result of Morgan’s efforts, Parker would read law for three years, but because he was ineligible for American citizenship (the American Indian Citizenship Act was not passed until 1924) Parker abandoned his quest to become an attorney, and earned a degree in civil engineering at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. Less than two decades later, Parker volunteered for the Union army, achieving the position of adjutant to General Ulysses Grant. As his service concluded, Parker drafted the surrender documents that General Robert E. Lee signed at Appomattox, ending the American Civil War. In 1869, Grant, now the President of the United States, appointed Parker – who retired at the rank of brigadier general – as the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. Parker was the first Native American to serve as commissioner – there would not be another until 1966.

Both men were young when they met in the spring of 1844. Morgan was 26 years old, and Parker was only 16. For the next seven years their lives would become intertwined in ways that proved to be mutually beneficial.

Morgan’s Value to the Tonawanda Seneca

According to most tellings, the chance meeting of Morgan and Parker in an Albany bookstore was productive because Parker and Morgan could each offer something that the other needed (e.g., Resek, 1960:27). Parker did not travel to Albany alone. He was there to serve as a translator for a delegation of Seneca leaders, who were visiting Albany – the capital of the state of New York – with a purpose. They were seeking a means to restore their land base, which had been claimed by investors in the Ogden Land Company through legal but unscrupulous means. By 1838, all Seneca lands had been lost in court proceedings. Meeting Morgan – who was a practicing attorney – in the bookstore thus presented an opportunity, and Parker invited Morgan to meet the Seneca delegation.

Morgan’s value to the Seneca went beyond his own knowledge as a lawyer. Morgan had an extensive social circle, and he was able to rally support among other professionals. In short order, the struggle to recover Seneca lands became a cause celebre among New York professionals. The effort went beyond court battles to cultural diplomacy. The governor of New York voiced his support for the Seneca, and soon a new antiquities exhibit opened at the New York State Museum to display Seneca artifacts (Saul, 2000). Morgan donated items to the museum, but many were created or collected by Ely Parker and his siblings for that specific purpose. The goal was to educate white New Yorkers about Seneca lifeways, and build support for their efforts to avoid removal to Indian Territory (Oklahoma).

In the end, the court struggle and public campaigns were only marginally successful. In 1857 the Tonawanda gained the right to repurchase 7,000 acres of their lands and they avoided removal. But even today the Tonawanda Reservation consists of a postage size parcel on the boundary of three counties in far western New York.

But in 1844, when the Seneca delegation first met Morgan, all hope was not lost. For the next six years, Seneca leaders worked to develop ties with Morgan and other sympathetic whites who might work for their benefit. Parker and his siblings taught Morgan about Iroquois social organization, beliefs, and ways of life, and in 1847, to his great excitement, Morgan was adopted by the Parker family and given the Seneca name of Donehogawa.

The Value of the Parker Family to Morgan

While it seems clear why the Parker family was interested in befriending Morgan, it is reasonable to ask why Morgan had such a deep interest in visiting the Seneca reserve to observe ceremonies, collect artifacts, and interview Parker and his siblings. The answer is that prior to meeting Parker, Morgan had become deeply involved in the study of “Indian Lore” and founded a society dedicated to what Philip Deloria calls playing Indian (Deloria, 1998). Deloria documents a rich history of American colonists dressing up as Indians, extending from the Boston Tea Party through the Boy Scouts. Morgan was far from unique in his passions, but he was more serious than most.

As it happened, Morgan completed his law degree on the eve of an economic downturn, and found himself unemployed, with time on his hands. Together with friends in a similar situation, he formed a society called The Gordian Knot. Their goal was to create a distinctively American Enlightenment, and initially they looked to Antiquity for inspiration. Together they studied ancient Greek philosophy, art, literature, and political systems, and Morgan published a series of related papers in 1843. But they soon lost interest in Antiquity, and decided that the real roots of the United States lay not in ancient Greece, but in aboriginal America. Given that they lived in New York State, they chose to model their new society on the Iroquois peoples, particularly their system of government and law, and their ceremonies. Their new order was named, interchangeably, The New Confederacy of the Iroquois and The Grand Order of the Iroquois. The new Order quickly added members from the professional classes, and chapters were formed around New York State. Helped by the economic downturn and the need to network, its membership peaked at over 400 in 1846.

Morgan, much more than anyone else, was passionate about getting the details correct. He was seriously committed to the idea that white Americans were the cultural heirs of Native peoples – a common cultural theme in the 19th century United States – and for the New Confederacy to reap its inheritance it was necessary to get the details right. But Morgan faced a serious barrier: he did not know any Iroquois people. There was no one to teach him how to dress authentically, or conduct ceremonies properly.

That changed when he crossed paths with Ely Parker.

In 1844, the same year he met Parker, Morgan began publishing a series of “letters” – initially under a pseudonym – detailing Iroquois social and political organization to the extent that he understood it. In 1845 and 1846, as the Grand Tekarihogea of the New Order, he pressed the membership to adopt authentic Iroquois dress, names, and ceremonies, down to the last detail. In 1847, a new Grand Tekarihogea was installed, and concerns about authenticity were jettisoned. The economy was rebounding, and the momentum of the Order collapsed. The final meeting of the New Order was held in 1847 (Tooker, 2001: 37).

Morgan was undeterred. He continued his efforts to learn about Iroquois society for four more years, stopping only in 1851, when he collected his accumulated letters into his first book, League of the Ho-Dé-No-Sau-Nee, Or Iroquois. That same year he married, and for the next five years he focused his efforts on accumulating wealth as an investor in railroads and mines in the Old Northwest of Michigan.

Parker as an Excluded Ancestor

In his Preface to the League of the Ho-Dé-No-Sau-Nee, Or Iroquois, Morgan stated that his purpose was to improve “the public estimation of the Indian” by replacing “imperfect knowledge” with more accurate understanding. He argued that accurate knowledge “brings before us the question of their ultimate reclamation” and even the possibility that Indians might be “raised to the position of citizens of the State.” And toward the close of his Preface, he dedicated the book to Ely Parker, noting his intellectual debt:

[I am] indebted to him for invaluable assistance during the whole progress of the research, and for a share of the materials. His intelligence and accurate knowledge of the institutions of his forefathers have made his friendly services a peculiar privilege (Morgan, 1851).

The word peculiar can mean unusual as well as strange, and it would appear Morgan meant the former. But arguably there was something strange about their relationship. There was an inequality built into their interactions, that extended to the gravity of their alliance.

Morgan was dependent on Parker for access, translation, and direct knowledge of Iroquois life. Without Parker’s knowledge and assistance, Morgan could not have gained national recognition as an expert on the American Indian after 1850. Morgan’s expertise appropriated Parker’s expertise, but only Morgan’s had public visibility. The question emerges: Why didn’t Parker produce his own ethnography of the Seneca Iroquois?

It wasn’t illiteracy. In fact, Parker kept a notebook of his ethnographic work, which included observations on Morgan and other whites who traveled with him. Parker composed a number of exceedingly humorous and well written letters that he mailed to Morgan, making sport of Morgan’s clumsy efforts to participate in reservation life (Deloria, 1998; Michaelson, 1996). One memorable letter, titled “Report of the Adventures of Lewis Henry Morgan” opened with a description of the inability of Morgan and his entourage to step into a Seneca canoe – an irony given that Morgan was posing as an expert in Seneca culture. Parker also recounted a long day and evening of speech making. Morgan patiently sat through the long day, although he could not comprehend a word that was said due to his lack of knowledge of the Iroquois language (the letter is printed in Tooker, 2001).

Oddly, despite the fact that Morgan knew very little about the Iroquois, Parker was dependent on Morgan to communicate accurate knowledge about the Iroquois to the citizens of New York. The fate of the Seneca hung in the writings of Morgan.

There is an added peculiarity to their relationship.

Morgan’s Preface conveys the sentiment that the Iroquois as such no longer exist. The theme of the “vanishing Indian” was common in American literature, and that is not surprising, given practices of that would be termed ethnic cleansing and genocide in the 20th century. But in Morgan’s rendering, it meant that Morgan and Parker were equidistant from the true Seneca people. Morgan speaks of the Seneca leaders as “descendents of the Iroquois” rather than as living, present, contemporary Seneca leaders, and he congratulates Parker for his “accurate knowledge of the institutions of his forefathers” – rather than for his knowledge of the living culture he was born into.

Philip Deloria finds deeper irony in Parker and Morgan’s collaboration. He sketches a scene reconstructing the evening when Parker, a native youth fluent in English, wearing professional, Euroamerian dress, and aspiring to read law, attending a New Confederacy meeting as Morgan’s guest. Wearing a suit, Parker enters a room full of white professionals, many of the lawyers, doing their utmost to wear authentic Iroquois garb and conduct meetings in an authentic Seneca fashion.

Deloria notes that no member of the New Confederacy had ever met a living Indian prior to meeting Parker. Given the power relations involved, Morgan and his associates were not only able to “dress native without ever confronting a native person” – even more, the authenticity of their dress depended on the absence of Indians from their meetings and their communities. For non-native citizens of the United States to claim to inherit the spirit of non-citizen Native people, those people had to vanish. And in fact the drastic impact of Jacksonian democracy and Indian removal – a process impossible to distinguish from what today is called ethnic cleansing – was still impacting Native peoples across the United States.

Shifting from a national to a personal scale, Morgan’s expertise as an expert on Iroquois culture depended on erasing Parker’s presence in his text, reducing him to the role of what later fieldworkers would call an informant, someone who is there to be consulted but whose knowledge changes ownership, becoming the expertise of the ethnographer once they return home (Deloria, 1998).

Deloria’s larger lesson is that anthropological ethnography – in a colonial context – can only exist when anthropologists bring to their work the power and sponsorship of the colonizing state, which introduces a disparity that makes it possible not only for the land and labor of colonized people to be exploited, but for their knowledge, beliefs, customs, and ways of life to be appropriated. It is an odd practice: good ethnography requires at one and the same time both personal intimacy, and a deep and fundamental social divide, the first achieved through time spent in “the field” with generous hosts – the second by participating in social practices that open a gap between them, allowing one to publish, and the other to be compensated with very modest payment.

As Deloria notes, Morgan’s interest in the “vanishing Indians” of New York State started out as a hobby that grew into an obsession. It changed the course of his life, but it was not obligatory. He could have changed his mind, and in fact, he repeatedly abandoned his studies when he had other concerns. For Parker and the Seneca leaders, on the other hand, saying no to Morgan carried severe consequences, including removal to Indian Territory, a thousand miles from their ancestral homes.

A Note on Arthur C. Parker, Ethnographer

After his collaboration with Morgan, Parker seems to have left ethnography behind. He may have had little interest in ethnography, it’s hard to know. Morgan assisted him in finding a position to read law, which he did for three years. He was unable to join the profession, however, because – with few exceptions – American Indians were not allowed to be citizens of the United States prior to the passage of the American Indian Voting Rights Act of 1924. Parker shifted his attention to civil engineering, earned a degree, and was widely respected. But he left ethnography behind.

Ely Parker’s great nephew, Arthur C. Parker (1881-1955), did develop a lifelong interest in anthropology. Arthur worked his way into a career in anthropology during the early 20th century. Arthur Parker was employed primarily at museums in New York State. He published widely, and achieved regional recognition – including serving as the first president of the Society for American Archaeology in 1935-1936. But his most widely circulated writings were popular books describing “Indian lore” to children (Parker,1927). They became the basis of Boy Scout Handbooks, and continued the mission of cultural diplomacy launched by the Parker family in 1844.

MORGAN INVENTS KINSHIP

It has become part of the lore of anthropology that Morgan’s League of the Ho-Dé-No-Sau-Nee, Or Iroquois, can be considered “the first scientific treatment of an American Indian people” (e.g., Starna, 2008). That might give us pause. The significance of Morgan’s work for 20th century anthropology, and the reason why he has been treated as a canonical thinker, has less to do with his League as such than his “discovery” or “invention” of the comparative study of kinship and marriage, a subfield that came to be called social anthropology in Britain after 1900 (Trautmann, 2008).

Morgan is remembered for three contributions to the study of kinship. First, his 1851 description of matrilineal descent in the League of the Ho-Dé-No-Sau-Nee; secondly, his massive 1871 work Systems of Consanguinity and Affinity of the Human Family, which established the comparative study of kinship terminologies as a fundamental topic; and thirdly, his 1877 effort to write a conjectural history of humanity. This work, Ancient Society, while capturing the attention of the communist revolutionaries Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, would draw disdain from 20th century cultural anthropologists, including Robert Lowie, who named Morgan’s approach unilinear evolutionism. These three books in combination explain why Morgan has been credited with creating social anthropology as a field centered on the study of kinship and marriage.

Matrilineal Descent and the Matriarchy Debate

As we discussed in an earlier chapter, Joseph-François Lafitau has been named the “Father of Social Anthropology” for his discovery of the patterns in Iroquois kin terminologies and rules of descent over a century prior to Morgan’s meeting with Ely Parker (Fenton and Moore, 1969). Lafitau’s major work – Customs of the American Indians Compared with the Customs of Primitive Times – was published in French in 1724. It was not translated into English until 1974. Perhaps for that reason, Morgan never read it – he doesn’t cite it, and never mentions it anywhere in his writings. Fittingly, Morgan would independently rediscover the distinctive pattern of Iroquois kinship and describe it in his 1851 volume League. One of Morgan’s discoveries relates to what later social anthropologists would term unilineal descent, and more specifically a form of unilineal descent called matrilineal descent. Let’s pause and watch this ten minute video:

An Introduction to Descent

House, Kendall. 2014. What is descent? YouTube video.

The Iroquois, including the Seneca, followed a system of matrilineal descent. Key properties, including long-houses and fields where corn, beans, and squash were planted, belonged to corporate groups of women, who were related through an exclusively female line. Men would grow up in the long-house of their mother, and then relocate upon marriage to the long-house of their father, whereas daughters would remain in the long-house of their mother. Later social anthropologists would call this a matrilocal post-marital residence pattern.

Sorting this out was difficult for most Europeans and Euroamericans. The technical terms I am using – such as matrilineal descent and matrilocal residence – did not come into use until the early 20th century, and there was no clearly organized conceptual framework for making comparisons. But Morgan was deeply intrigued.

Like later aspiring ethnographers from similar upper middle class social backgrounds in Europe and the United States, Morgan was particularly interested in two aspects of Iroquois kinship. First, the implications of unilineal descent for marriage patterns among cousins. Cousin marriage was practiced not only by the fading nobility, but also among members of the new business classes (Kuper, 2002; Kuper, 2010). Darwin had married his first cousin, and so had Morgan. Close marriages helped keep property among close relatives, and assisted in the concentration of wealth.

The Iroquois, as it happened, sorted out two categories of cousins. One category later anthropologists would call cross cousins (the children of a sibling of a parent of opposite gender, for example, the daughter of mother’s brother), the other category would be known as parallel cousins (the children of a sibling of a parent of the same gender, for example, the daughter of mother’s sister). The English did not make this distinction. A cousin was simply the offspring of the sibling of a parent. The Iroquois system did not allow marriage between parallel cousins, whom they referred to as brother and sister and considered siblings. But it did allow for marriage between cross cousins, and in doing so, created a bond between two corporate descent groups or clans.

In addition to the light it might throw on cousin marriage, Morgan and other emerging social anthropologists were deeply interested in the relationship of matrilineal descent to what was called the woman question. The woman question was a contentious debate about the proper roles of women in European and Euro-American society, especially in regard to their autonomy. In the traditional model “respectable” women were in a dependent role for the length of their lives: first as daughters and sisters, and later as wives, in the custody of their father, brothers, and husband. Their proper sphere of activity was domestic, in the household of their father or husband, and in their church. Women in the community who tried to live outside these roles were considered disreputable.

Younger women who did not marry in a timely fashion, and women who were widowed, were somewhat scandalous, and potentially dangerous, particularly if they engaged in activities outside their household that exceeded religious obligations. As the decade of the 1860s approached, debates arose concerning women’s access to education, participation in professions like anthropology, and ownership of property, all of which might increase their autonomy. But even more worrisome was the possibility of divorce and remarriage. Because a marital union was permanent, a widow might never remarry. But in the middle of the century, the possibility of divorce was more openly discussed, as well as the possibility of remarriage, particularly when it involved the sibling of the deceased spouse (i.e., when a widowed woman married the brother of her deceased husband, or, contrariwise, when the husband of a deceased wife married her sister (Kuper, 2010). Twentieth century social anthropologists would call these practices the levirate and the sorrorate respectively.

What was remarkable about the Seneca system, in this context, was the prominent role and autonomy of women. Women owned the house and gardens, which were the most important kinds of property. They could initiate divorce from their husbands. And although matriclans had male leaders, they also had female leaders,and these elder women both selected the male leaders and could depose them. Moreover, their approval was needed before major decisions like going to war could be taken. During the 1860s, such societies were known primarily to anthropologists, who called them matriarchies.

Clashes over divorce and cousin marriage in England and America thus gave rise to arguments over the priority of patriarchy as opposed to matriarchy in the 1860s. Priority could mean earliest, or simply normal. The debate was over whether one form was the common foundation of the human condition and the other as an unusual breach. Darwin and Sir Henry Maine, among others, championed the priority of patriarchy, while Morgan, along with the Scottish ethnologist John McLennan and the Swiss philologist Johann Bachofen. Argued for the priority of matriarchy.

Was Morgan then a feminist in the context of the 19th century?

Morgan certainly held advanced views on the woman question, and he did take some action. In 1852 Morgan backed an effort to launch the Barleywood Female University alongside his alma mater, Rochester University. Enrollment at Rochester was limited to male students. Morgan’s goal was to secure access to higher education for women in New York State. The effort ultimately failed (Bove, 2018). However, before applauding, it is worth noting that the feminist leader Susan B. Anthony was a resident of Rochester, but there is no record in the papers of either Morgan or Anthony that they ever spoke to one another (Tooker, 1984). The abolitionist Frederick Douglas also lived in Rochester, but again, there is no indication they ever visited with one another.

Female Ethnographers and Excluded Ancestors in the United States

Given the restrictions of their time, it is somewhat remarkable to learn that there were women anthropologists who achieved considerable professional recognition and autonomy in the 19th century. Two women gained particular prominence in the United States, and could be considered excluded ancestors were it not for the sizable literature that has developed around each of them. Each of these female ethnographers also collaborated closely with indigenous researchers of distinction who, despite growing recognition, remain underappreciated.

Matilda “Tillie” Coxe Stevenson (1849-1915)

Coxe Stevenson was the wife of James Stevenson, a geologist who gained employment working for the Bureau of American Ethnology (BAE), which was a subsidiary of the United States Geological Survey administered by John Wesley Powell. After brief “ethnographic” excursions in 1878 among the Ute and Arapaho, the Stevenson’s joined the first official BAE expedition, and traveled to Zuni Pueblo in New Mexico. Like all BAE ethnographers, Coxe Stevenson was self-taught. Her goal was to collect as much ceremonial knowledge as possible, while her husband loaded wagons with “material culture” for display at the Smithsonian Museum. Their work at Zuni would last three years, and today is very controversial – in his notes James documented his willingness to steal objects the Zuni were unwilling to part with, while Matilda was known for pressuring people to share esoteric knowledge they were not free to share. In recent decades, considerable effort has gone into repatriating items “collected’ by the Stevenson’s to the Zuni people.

We’wha as an Excluded Ancestor

The success of Coxe Stevenson’s research at Zuni appears to owe in large measure to her decision to hire a Zuni person known as We’wha (1849-1896) as her maid and assistant. We’wha cleaned, managed a garden, and cooked for Coxe Stevenson, and became her closest confidant and most important collaborator. Within the Zuni world, We’wha was a special kind of person known as a lhamana, who blended male and female qualities, wore a combination of male and female clothing, and worked at both male and female tasks. In a report over two decades after they met, Coxe Stevenson described We’wha as follows (Stevenson, 1904: 310):

A death which caused universal regret and distress in Zuni was that of We’wha, undoubtedly the most remarkable member of the tribe. This person was a man wearing woman’s dress, and so carefully was his sex concealed that for years the writer believed him to be a woman. Some declared him to be an hermaphrodite, but the writer gave no credence to the story, and continued to regard We’wha as a woman: and as he was always referred to by the tribe as “she” — it being their custom to speak of men who don woman’s dress as if they were women — and as the writer could never think of her faithful and devoted friend in any other light, she will continue to use the feminine gender when referring to We’wha.

Because of their distinct gender identity, We’wha was widely respected as a spiritualist and for their esoteric knowledge. Rather than collecting existing objects, We’wha produced baskets, pottery, and weavings for the Stevensons. Through their employment with Coxe Stevenson, We’wha developed fluency in English, and was invited to lead a Zuni delegation to Washington D.C. in 1886, where Whe’wa met President Grover Cleveland, Senators, Congressmen, and federal officials, and was celebrated in the press as a “Zuni princess” of unusual stature (Coxe Stevenson noted that We’wha was the tallest person in Zuni). All of this came with personal peril. Accused as a witch along with other Zuni who were close to outsiders, turmoil arose in the Pueblo, and the US military arrested and imprisoned We’wha, who died in 1896.

Alice Fletcher (1838-1923)

Alice Fletcher lived her life as a single woman who became involved in early American archaeology and developed a reputation as a professional ethnographer. Her interest came rather late in life, as she approached 40 years old. She worked at major museums (including Harvard’s Peabody Museum) and on major archaeological and ethnographic surveys (Fletcher, 2020; Mark, 1988).

During the 1880s Fletcher primarily worked as an active advocate for Indian assimilation, playing a prominent role in two federal programs that are today bitterly remembered and critiqued. She supported the boarding school movement, and worked at the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania, the prototype of board schools, where strict discipline was intended to transform Indian children into English speaking, God fearing, manual laborers. She also co-authored federal legislation known as the Dawes Allotment Act, which passed in 1887.

The objective of the Dawes Act was to detribalize Native people and transform them into individualist farmers by dissolving communally held lands and distributing them as individually held parcels. Under the plan, communal lands, already greatly reduced by the reservation system, were allocated to individuals, in a manner that always left “surplus” lands to be distributed to non-Indian settlers through lotteries. In addition, once tribal members were considered “competent” to function in “white society” – a competence usually decided by “blood quantum” – taxes were imposed on their parcels that often went unpaid, leading to forfeiture. Between 1887 and 1934, tribal lands in the United States decreased roughly two-thirds. The Dawes Act hollowed reservations across the American West, producing a situation where the majority of tribal lands belong to non-Indian owners (Gay, 1987).

Were it not for the fact that Fletcher helped write the Dawes Act, she might be viewed as an early “applied anthropologist” who supported herself by taking employment in her chosen profession as it offered itself. Many female and minority anthropologists have encountered similar circumstances. At no point, however, did Fletcher’s scholarly output decline – she authored dozens of reports having nothing to do with allotment or boarding schools, published by major anthropological institutions, in a steady stream from 1883 to 1920. She received fellowships from the Peabody Museum, served as President of the Anthropological Society of Washington and the American Folklore Society, and was an active member of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Francis La Flesche as an Excluded Ancestor

It was remarkable, given the normalization of violent prejudice and the very real dangers to non-conforming individuals at the time, that Alice Fletcher was able to make her way in the world as a single woman, and achieve recognition as a professional scholar. It is perhaps even more remarkable that for most of her professional life, she lived with and traveled with an Indian man. When they first met she was 43, and he was 24. The twenty year age difference enabled them to pass as mother and son, and it is said that she “informally adopted” him (Porter and Roemer, 2005). His name was Francis La Flesche.

Francis La Flesche and his siblings were members of a prominent family in the Omaha tribe, and they initially played a role with Fletcher analogous to the Parker family with Morgan. It was Francis’s sister, Susette, who initially worked with Fletcher. But shortly after 1880, Fletcher began working with Francis, and their collaboration lasted nearly four decades. Unlike Ely Parker, La Flesche was able to earn a law degree, but he never practiced. Through Fletcher, La Flesche was appointed as an assistant ethnologist by the Bureau of American Ethnology – the first Native employee of the BAE. But much of his work seems to have been invested in supporting Fletcher’s research, especially among the Omaha, where he served as translator and field researcher. Their work culminated in a massive report to the BAE titled The Omaha Tribe (Fletcher and La Flesche, 1911).

Francis La Flesche’s first independent publication, The Middle Five, was a memoir of growing up on the Omaha Reservation and attending school, an account that differs markedly in tone from later portrayals of boarding schools (La Flesche,1900). Although he was a member of the Omaha tribe, and worked with Fletcher developing their joint work, his own preference was to work among the Osage. The Osage and Omaha are closely related, but they are distinct peoples and communities, and La Flesche found it more comfortable to work across social distances than to work among family and friends. The richness of his writings on the Osage has only recently gained recognition (La Flesche, 1999).

KINSHIP TERMINOLOGIES AND THE QUESTION OF HUMAN UNITY

After publishing League in 1851, Morgan focused on his work as a lawyer. He became involved in mining and railroads in the Old Northwest, especially Michigan. Yet his interests repeatedly extended beyond work. Over the course of the next decade, Morgan joined the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and took advantage of his trips to Michigan to develop expertise on the natural history of the American beaver, and continue his ethnological inquiries, now with members of the Ojibwa people. Morgan’s new ethnographic work was much more focused than earlier. The direction of this work was foreshadowed by two papers, published in 1857 and 1859, that seemed to be arid, technical, and abstract, but in truth held the seeds of his most sustained intellectual interest (Morgan, 1857; Morgan, 1859). Both papers concerned what later social anthropologists would call kinship terminologies.

An Introduction to Kin Terminologies

Kinship terminologies can be quite difficult to apprehend at first glance. I recommend viewing the following short ten minute video at this point:

House, Kendall. 2014. What is an Iroquois Kin Terminology? YouTube.

Using the technical vocabulary developed by social anthropologists in the 20th century, we can say that the distinctiveness of an Iroquois (or classificatory) kin terminology is that a parent’s parallel siblings are also called mother and father. Parallel siblings are siblings whose gender is the same. Thus, father’s brother is a parallel sibling, and so is mother’s sister. Accordingly, father’s brothers are also fathers, and mother’s sisters are also mothers. This distinction is carried down to the next generation, so that sibling terms are applied to the children of mother’s sisters and father’s brothers.

In contrast, cross siblings – mother’s brothers and father’s sisters – fall into a different category, and so do their children.

Morgan found this distinction of great intellectual interest. But in 1859 he realized that it held the key to advancing the monogenist cause. Explaining Morgan’s commitment to monogenesis will require a long but necessary digression.

Deep Time and the Paradigm of Time Travel

You will recall that a core issue in the debates between Las Casas and Sepulveda concerning sixteenth century New Spain centered on the question of human unity. Bartolomé de las Casas insisted that “all mankind is one” – Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda disagreed. Their positions had what today would be called policy implications: if humanity was plural rather than the same, then people did not have to be treated the same. Those who were different could be enslaved, murdered, and plundered, without moral regret. Those who were the same could not.

In the centuries that followed, the issue did not go away, nor did the policy implications change. In the seventeenth century, Joseph-François Lafitau repeated the position of las Casas, insisting that there had been but one genesis and all humans descend from Adam and Eve and, more proximally, the sons of Noah. Unlike Las Casas, Lafitau worked to assemble a massive body of evidence that he felt demonstrated connections between the ancient life of Europeans and the contemporary lives of Native Americans. In this he echoed the sentiments of John Locke, a century earlier:

“ Thus, in the beginning, all the world was America, & more so than that is now”

The equation of societies around the world with the European past became the founding proposition of 19th century archaeology, which operated on two fronts. On the one hand, there were increasingly convincing demonstrations that the ancestors of Europeans had lived “stone age” lives that had much in common with the lives of contemporary hunting peoples who were observable around the world. In 1800, the French ethnologist Joseph Marie de Gerando (1772-1842) proposed the method of philosophical time travel: to leave the centers of European civilization, and voyage out around the world, was to travel back in time, into the human past, and observe how Europeans had once lived.

During the long decade of the 1860s, anthropologists asserted an equivalence between the two forms of inquiry: to travel to the contemporary Pacific, or to Sub Saharan Africa, or to Native America, was equivalent to working through geological strata, and discovering past ages before recorded history. Ethnology and archaeology were two roads to a human past before recorded history.

The Four Paths of Anthropological Science

The question that arose in the middle of the 19th century was this: Was the prehistoric world pre-Biblical? And if Biblical accounts were unreliable, how could the past be known? How could questions of human origins be decided? How could the relationships between the varieties of humankind be determined?

In the decades leading up to 1860, answers to these questions were quickly developing, as early forerunners to anthropology traveled the world, collected ethnographic data, offered theories for the origin of everything but human physical forms, and documented human variation in all its expressions. By 1860, there were four paths to answering these questions: prehistoric archaeology, physical anthropology, philology (the history of languages), and the description and synthesis of direct observations of living peoples (ethnography and ethnology).

Monogenists and Polygenists

If anthropology occurred in a social vacuum, isolated and closed to the world around us, it might be possible to ask purely scientific questions and offer strictly scientific answers. But that has never been the case, and it probably never will be. And as anthropology began to take shape, a fundamental issue proved capable of solution only by force of arms. It is of great significance that the American Civil War (1861-1865) was fought at the center of the decade when anthropology matured.

At the onset of the long decade of the 1860s, the use of the words Monogenist and Polygenist in published works suddenly soared. If we do not understand what these words refer to, we cannot understand 19th century anthropology.

Monogenism literally translates as “one genesis.” Monogenists embraced a “short chronology” and insisted that the Biblical account of creation, from the formation of the world to the Garden of Eden, the Great Flood, and the Tower of Babel, accounted for the histories of all people everywhere. There had been but one creation, and humanity was one. Contemporary human varieties reflected a general trend toward degeneration from Adamic perfection, but the differences were slight. As the German romantic scholar Johann Gottfried Herder insisted, in response to Kant’s concept of race: “races do not exist!”

Polygenists were skeptical of this account. Polygenists argued that humanity was the product of many creations. Here they offered two contrary proposals. Some held that the differences between humans were too great to have developed in a few thousand years, and the Biblical chronology was far too short. Others expressed doubt that any change had happened in God’s creation: Can a leopard change its spots? Degeneration could not explain human differences.

Some polygenists embraced atheism, others proposed that the Biblical account had only regional relevance – to the peoples of the Near East and Europe – and that the history of humanity went deeper and broader than the Bible suggested. The peoples beyond what came to be called the “white” world had been created separately. According to some proposals, non-whites were pre-Adamites. Moreover, the differences between the races of mankind were fundamental, on the order of those between species.

Table 1: Comparison of Monogenists and Polygenists

| Monogenists | Polygenists | |

| Creations | One | Many |

| Human Differences | Degeneration from original form | Stable since creation |

| Human Unity | All Mankind is One | Each Race is Distinctive |

| Human Equality | Democratic Inclusion | Racial Hierarchy |

| Slavery Question | Abolition of Slavery | Pro-Slavery |

Their debate was far from coldly academic. In the centuries after Las Casas and Sepúlveda made their cases in Castille, slavery had grown from an enterprise affecting a few thousand people to the largest business in the world: millions of people were enslaved, and many of the most profitable enterprises in the world were powered by forced labor. Nor was slavery an arbitrary fate. While compulsion to labor for others took many forms in the European colonies, including indentured servitude that had an exit, and while white laborers as well as people of color were forced to work at difficult jobs for little pay, slavery was overwhelming racial, and the plantations of Brazil, the Caribbean, and the American South swallowed millions of African lives in conditions that required brutal forms of repressive violence to sustain.

The divisions between monogenists and polygenists were deep enough that in the long decade of the 1860s British anthropology divided into two learned societies. The Ethnological Society of London was formed in 1843 by James Cowles Prichard, a committed monogenist and abolitionist. As the United States drifted toward civil war, tensions boiled in the ESL, and polygenists who had joined the society, including James Crawford, Robert Hunt, and Robert Knox – about whom, more later – attempted to seize control, and, failing that, started their own learned society in 1863: the Anthropological Society of London. But if the ultimate cause of the split – which lasted until 1871 – was racial slavery, the proximal cause was the woman question and the decision to allow women into the ESL. A rather heterogeneous group of scholars – all opposed to allowing women to attend meetings – abandoned the ESL for the ASL.

Polygenesis, Phrenology, and Physical Anthropology

Polygenists promoted their approach as a new science that would bring human history into the sphere of natural history. They claimed to be driven by the careful description and analysis of anatomical, artifactual, geological, linguistic, and ethnographic evidence – religious dogma and the Bible be damned. They dismissed the monogenists as sentimentalists, hopelessly attached to Biblical dogma. But despite their rhetoric of scientific rigor, they made claims that greatly exceeded what their evidence could support. Like the monogenists, the polygenists had a political agenda. They defended systems of racial slavery that treated slaves as private property without legal standing, and argued for the restoration of racial slavery in the British colonies, where slavery had been abolished in 1830. The British government took on the greatest debt in the history of Britain to compensate slave owners for the loss of their human property. As a result, the outcome of the debate was consequential not just to British anthropologists, but to wealthy investors and a variety of political interests.

The polygenists were a varied lot. In the United States, they included some southerners, like Josiah Nott (1804-1873) of Mobile, Alabama, as might be expected. But the most prominent American polygenist was a professors at Harvard University. Louis Agassiz (1807-1873) gained fame for discovering evidence for ice advances and retreats – and the concept of ice ages. But Agassiz was also a racist and proponent of polygenism. Agassiz championed the argument that the world consisted of natural zones, each of which represented a separate creation. Remarkably – given his awareness of geological change – he argued that the organisms created by God in those zones had not and could not change.

There were strong ties between the American and British polygenists. Part of this reflected the influence of the University of Edinburgh in Scotland, where American’s like Samuel Morton (1799-1851) traveled to study surgery and ended up learning phrenology from the Combe brothers, who founded the Edinburgh Phrenological Society in 1820. The phrenologists proposed that humans were material entities, capable of scientific explanation like any other material process. The key to understanding human behavior was the brain, and the key to understanding the brain was the skull. A close examination of the skull could reveal all aspects of a person: their character, intelligence, morality, and propensities, including those toward deviance and crime. Morton’s innovation was to shift phrenology from the medical examination of individuals, to the character of races. Partly owing to Blumenbach’s precedent, and partly owing to phrenology, amassing collections of skulls for comparative analysis became the central research practice of polygenists.

For several decades, phrenology was something of a fad among medical doctors in Britain and America, but it lost steam both for its theoretical failures and a series of scandals. Most notable was the fall from grace of Robert Knox (1791-1862) who, like other anatomists of the time, struggled to obtain human cadavers to dissect. After purchasing the cadaver of a lodger who passed away in an Edinburgh boardinghouse, Knox proceeded to pay generously for 16 more, which the landlords gladly provided, by means of 16 murders.

Nineteenth century physical anthropology was the domain of surgeon’s trained in anatomy and accustomed to dissection, and the collection of cadavers – and the resulting holding of human remains by museums of anthropology – became a normal part of the profession. The easiest cadavers to obtain were from people as vulnerable in death as when living, including inmates, bodies that went unclaimed at morgues, but also through robbing fresh graves. Around surgical schools networks of cadaver collectors developed, and similar networks were developed by physical anthropologists to build collections representing “the races of mankind.

The collections that resulted from these practices have been the focus of a series of public scandals in recent decades, a recent example occurring in August, 2023, and the collections amassed by a Czech-American physical anthropologist named Aleš Hrdlička (1869-1943) – who we will meet in the next chapter. For decades, the Smithsonian Institution kept and curated Hrdlicka’s collections, but that is a legacy the museum now wishes to bring to a close (Dungca, Healy, and Ba Tran, 2023).

The Crisis of Monogenism in the 1860s

In Britain, the emerging fields of anthropology, ethnography, and ethnology had long had monogenist foundations. Concepts that are strongly associated with 19th century anthropology in current textbooks – like unilineal evolutionism, the psychic unity of mankind, and independent invention – are all monogenist concepts. They all assume the unity of humanity. But they often overlook how embattled monogenists were for much of the century.

The British monogenists were led by James Cowle Prichard (1786-1848). Like his German predecessor – Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (1752-1840) Prichard was convinced of three things: all humans were the product of a single creation; the differences between human varieties was slight; and those differences could be accounted for by degeneration. Prichard was of Quaker background, and beyond his research – which he called ethnography – he supported the founding of the Aborigines Protection Society in 1836. Prichard was also an ardent abolitionist, who campaigned tirelessly not only for the end slavery in Britain’s colonies, but to British participation in the slave transport and sale of slaves, and trade with slave powered industries, like the cotton industry in the American South.

If the polygenists focused their efforts on physical anatomy, Prichard preferred an approach that was precosciously holistic: although he was interested in physical remains, he relied on linguistic affinities to define human groups. Philology – the study of relationships among languages (now known as historical linguistics) – lay at the foundation of Prichard’s monogenist ethnology.

THE LIMITS OF PHILOLOGY

Early on, philology generated much excitement. For example, it was determined fairly quickly that German, Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, and English could be grouped as Germanic languages; that Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, and Romanian as Romance or Latin languages; and that Polish, Russian, Ukrainian, and Czech as Slavic languages. Excitement grew when less obvious connections were established, particularly those between European languages and the languages of South Asia, including Hindi (India), Farsi (Iran) and Pashto (Pakistan). By 1786, all of these languages had been convincingly grouped together in a larger grouping: the Aryan language family (today Aryan has been replaced with Indo-European).

But a problem arose: as philologists expanded their work geographically, and sought deeper relationships, their efforts hit a wall. They could group together Indo-European languages, and they discovered similar families in the America’s (e.g., Algonkian and Iroquoian), but they could not identify higher level connections. The world’s languages seemed to fall into zones that could not be linked together, and this seemed to support the polygenists.

Both Prichard and Blumenbach died in the 1840s, and as civil war in the United States loomed on the horizon, pro-slavery polygenists were growing in numbers and influence. And in the science war between anatomists and philologists, and in the sphere of educated opinion, the polygenists – with their anatomical focus – seemed to be gaining ground.

Kin Terminologies as a New Path to Origins

Morgan was very aware of the crisis impacting monogenesis. It was this awareness that led him to respond powerfully to an observation that otherwise might have gained no notice. In 1859, Morgan was working in Michigan, and his old habits led him to visit with a member of the Ojibwa community. Among other things, Morgan collected Ojibwa kin terms. Morgan had just published his recent papers on the Iroquois kinship, and he was struck by the observation that the pattern of Ojibwa terms grouped parallel siblings and their offspring in the same manner as a Seneca terminology. That observation led Morgan to dedicate eight years of his life to the comparative study of kin terminologies. He traveled to reservation communities across the American west, and sent queries by mail to travelers and missionaries around the world (White, 1951).

The reason for Morgan’s excitement stemmed from a simple but potentially powerful observation: although the Iroquois and Ojibwa followed the same kinship system, their languages belonged to different families. Ojibwa belonged to the Algonkian language, while Iroquois belonged to the Iroquoian family. No connection between these families had been determined. Morgan realized immediately that if kinship systems crossed the boundaries between language families that otherwise defied monogenist efforts to establish unity, then perhaps the study of the distribution of kinship systems could demonstrate the unity of humanity where philology failed.

In 1862, Morgan’s data gathering efforts ceased when he lost both of his young daughters to illness. But he soon returned to work, motivated by the bloodshed of the Civil War. The result was a massive manuscript titled Systems of Consanguinity and Affinity in the Human Family. Morgan’s Systems is one of the most influential books in the history of anthropology, but one of the least read. It’s sheer size makes it difficult to read. In addition, like many social anthropologists of his era, Morgan was a lawyer, and as a result many of the technical terms they introduced have Latin roots. In Latin, consanguinity refers to blood kinship, while affinity refers to marriage, or “kinship by law” (thus, most Americans speak of their ‘in-laws’). Like the Romans, most Americans believe they have “blood relatives” and “relatives by law.”

Morgan’s Systems laid the foundation for social anthropology, centering that field on kinship, marriage, and kin terminologies. The manuscript was so large that although it was completed in 1867, it proved so costly to print that publication was delayed until 1871, as the long decade of the 1860s concluded.

Morgan opened the Preface to Systems with this observation:

PHILOLOGY has proved itself an admirable instrument for the classification of nations into families upon the basis of linguistic affinities. A comparison of the vocables and of the grammatical forms of certain languages has shown them to be dialects of a common speech ; and these dialects, under a common name, have thus been restored to their original unity as a family of languages. In this manner, and by this instrumentality, the nations of the earth have been reduced, with more or less certainty, to a small number of independent families.

He continued, however, by noting that philology seemed to have reached its limits:

When this work of philology has been fully accomplished, the question will remain whether the connection of any two or more of these families can be determined from the materials of language.

This captured, exactly, the accomplishment and the limits of philology in the cause of monogenism.

Morgan next introduced his new method of demonstrating the unity of the peoples of the world: the comparative study of kinship systems. Based on the work he had accomplished, he predicted that the study of kinship would reduce all of the peoples of the world to just two categories, which he called descriptive and classificatory.

MORGAN AND THE UNIVERSAL HISTORY OF HUMANITY

The publication of Systems brought Morgan to the forefront of American anthropology, but it is worth noting one fact. Unlike League, this book would acknowledge no Native assistants or associates. After thanking by name a large number of Euroamerican dignitaries who assisted him on his travels out west and with his global mail survey, Morgan concluded with this statement:

There is still another class of persons to whom my obligations are by no means the least, and they are the native American Indians of many different nations, both men and women, who from natural kindness of heart, and to gratify the wishes of a stranger, have given me their time and attention for hours, and even days together, in what to them must have been a tedious and unrelished labor. Without the information obtained from them it would have been entirely impossible to present the system of relationship of the Indian family.

No names were provided.

Morgan’s European Vacation

The social distance between Morgan and Native people would grow wider in the next decade. In 1871 Morgan and his wife spent a year traveling in Europe. Before leaving, he published one of his final works: The American Beaver and His Works (Morgan, 1868). Anthropologists have had a hard time deciding what to make of The American Beaver, but Charles Darwin, who studied it closely as he worked on The Descent of Man and The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals, was ecstatic and eager to visit with Morgan when he reached England.

After returning to New York, Morgan focused on his final work. Succinctly titled Ancient Society, it carried a lengthy subtitle that would consign Morgan’s work to ignominy among 20th century cultural anthropologists: Researches in the Lines of Human Progress from Savagery through Barbarism to Civilization (Morgan, 1877). Morgan’s ethnocentric language has long made Ancient Society an exhibit of intolerance in introductory anthropology courses. But as you have probably gathered, the truth is more complex.

Interestingly, it is only in Ancient Society that Morgan employs the word “savage.” In Morgan’s League, the word savage appears once, in a reflection on the Iroquois passion for games, in a context where it brings into question the idea of wilderness (Morgan, 1851: 312).

The American wilderness, which we have been taught to pronounce a savage solitude until the white man entered . had long been vocal in its deepest seclusions, with the gladness of happy human beings.

In Systems “savage” appears three times in 656 pages. One use is from a quotation of a letter by a missionary in Fiji, a second is in a section where Morgan tries to describe a hypothetical ancestral human who is more animal than human. The third time is more problematic, as a description of the violence that characterized Iroquois warfare.

In Ancient Society, by contrast, savage, savagery, barbarian, barbarism, and related terms form the basic outline of the book. Morgan breaks human history into seven stages: lower, middle, and upper savagery; lower, middle, and upper barbarism, and lastly, civilization. This usage is consistent with European ethnology at the time, and the introduction of these terms seems to be the fruit of Morgan’s European vacation, where he visited not only with Darwin, but with leading British ethnologists – all monogenists – including Thomas Henry Huxley, John McLennan, Sir Henry Maine, and John Lubbock..

In the United States, Ancient Society would become not only Morgan’s best selling book, but the most influential ethnological work of the late 19th century. John Wesley Powell, the head of the United States Geological Survey and therefore the director of the Bureau of American Ethnology – which employed James and Matilda Coxe Stevenson, Alice Fletcher, and Francis La Flesche, among others – would unsuccessfully endeavor to adopt Morgan’s work as the theoretical framework for the B.A.E. – unsuccessfully, because the ethnologists at the B.A.E. were a highly idiosyncratic collection of quirky individuals, and they never followed any vision beyond their own emerging interests.

Ancient Society

Morgan’s Ancient Society was, more than anything else, a synthesis of the thoughts of European ethnologists with his own work. It was an effort to give a global, universal account of human history. Morgan was particularly interested in the emerging scholarly community of social anthropologists whose interests lay in the origin of the family and civic institutions. The conceptual framework of the book draws heavily on what Ronald Meek termed the four stage theory of the eighteenth century Scottish political economists, most prominently Adam Smith. Morgan sets out seven “ethnical periods” which he relates to stages in the growth of the “arts of subsistence.” His method draws heavily on the Scottish method of conjectural history: Morgan was not reluctant to make bold claims.

If the 1860s was the decade of Darwin, it was also the decade of social anthropology – which focused on the origin and development of the family, marriage, property, and government, and, after Morgan, systems of descent and kin terminologies. A spate of books appeared in short order. In 1861 Sir Henry Maine published Ancient Law, and Johan Jacob Bachofen published Das Mutterrecht. Maine held that the family began with patriarchy, Bachofen countered with the argument that in the beginning matriarchy predominated. A few years later, in 1865, John McLennan’s Ancient Marriage appeared – supporting Bachofen. Each of these writers influenced Morgan after 1871.

Following Sir Henry Maine, Morgan argued that there are two basic systems of government: one based on kinship (Societas) and one based on the State (Civitas). The history of humanity had been about making that transition. This had occurred due to mechanisms that were at once physical and mutable: kinship systems were, somehow, transmitted in the blood. His comparative ambitions grew – imitating the European ethnology – and he sought to address recent ethnographic work on aboriginal Australia with his own work on the Iroquois, as well as Polynesian societies and Greek and Roman antiquity. The overall impression a reader gathers is indeed that of a single human family, moving, unevenly, in a common direction. Importantly, Morgan attributed the uneven progress toward civilization not to inferiority, but to the play of chance, and the Grace of God.

A NEW FORM OF MONOGENISM: ON DARWIN’S ORIGIN

Perhaps because he eschewed Biblical frameworks, it is often overlooked that Charles Darwin was a lifelong abolitionist and that his sympathies lay with the monogenists. He insisted that the differences among human races were slight (Desmond and Moore, 2014). However, because of the challenge he presented to Christianity, by the late 19th century Darwin’s reputation had been effectively repackaged by a new generation of racial thinkers. The subtitle of the Origin of Species did not help (“The preservation of favored races in the struggle for life”) nor did Darwin’s belated adoption of Herbert Spencer’s evocative phrase: “the survival of the fittest.” And, for that matter, neither did Darwin’s expository strategy of rehearsing the arguments of his opponents as if they were his own, before skewering them, or his effort to balance the good and bad in all discussions..

But when The Origin of Species was published in 1859, polygenist thinkers were, as George Stocking notes, quick to identify it as “a new form of monogenism” and do everything possible to discount it (Stocking, 1986: 69). Out of these attacks came many persistent creationists critiques and memes, including the missing link.

Darwin, as much as Morgan, recognized the crisis that faced Prichardian monogenism. He repeatedly read Prichard’s Researches into the Early History of Man, identifying its flaws. And flaws there were. Prichard’s work was, in fact, not too different from the polygenist caricature of him: Prichard was committed to a short chronology, his degenerationism had no real mechanism for explaining how variation arose, he set aside anatomical variation in favor of language, his work was difficult to align with breakthroughs by geological thinkers like Charles Lyell and archaeological evidence of the antiquity of man (Grayson, 1983); and he would not introduce thinking that challenged the Bible.