9 Getting to Know You: How We Turned Community Knowledge into Open Advocacy

Lillian Rigling & William Cross

Introduction

Textbook affordability has been a priority for the North Carolina State University (NCSU) Libraries for the better part of the past decade. As a large public land-grant institution, NCSU has a deep commitment to welcoming all students, particularly first-generation students and those from underrepresented populations. As a science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM)-focused institution, NCSU must balance this commitment against the high cost of STEM textbooks, which are often significantly more expensive than textbooks for humanities courses. As the space on campus where students, faculty, the campus bookstore, and others can meet to work collaboratively, the Libraries have a unique opportunity to meet our own stated mission to be the “competitive advantage” for students working to navigate this challenging textbook marketplace. This chapter details our efforts to not only encourage the use of open educational resources on our campus, but also to understand how our students were navigating the information marketplace, and to educate and empower our students to leverage the rise of open culture into meaningful and sustainable support for open education.

Library Support for Textbook Affordability

Our initial efforts date back to a 2009 student-led proposal submitted to our University Library Committee, which led the NCSU Libraries to pilot a textbook lending program. In partnership with the NCSU Bookstores, the Libraries committed to purchasing at least one copy of every required textbook for fall and spring semester classes and made them available to students for a short-term loan. This program ensures that any student who does not have the funds to purchase a textbook can have access to the textbook through the Libraries. In the first year of the program, the Libraries purchased approximately 1,200 textbooks to seed the collection, and after the success of the pilot, we have continued to purchase around 700 textbooks each year. Textbooks are added to a “Textbook Collection” in our integrated library system (ILS) and interfiled with our traditional course reserves, available for a two-hour checkout in each library (Thompson, Cross, Rigling, & Vickery, 2017).

Our textbook lending program is designed to address an immediate burden of the cost of textbooks and learning materials on our students, but we also have taken steps to address the culture of faculty and departments assigning expensive textbooks to students by initiating library collaborations with faculty, students, and external partners to provide free or lower cost alternatives to traditional textbooks. In 2010, the Libraries partnered with the NCSU Physics Department to license a physics textbook used for all introductory physics courses. The Libraries paid a one-time licensing fee of approximately $1,500 to the publisher to allow all NCSU students to have free access to an electronic version of this textbook and any future editions through the library catalog (Laster, 2010; Rashke & Shanks, 2012). The impact of this program on our students did not go unnoticed by our students, faculty, and the media. Nearly 1,300 students take a physics course which requires this textbook each year, saving students nearly $90,000 in textbook costs annually.

The success of this open physics textbook laid the groundwork for the Libraries to continue to address the financial burden of buying textbooks through collaborating with faculty to seed innovation. In 2013, NCSU Libraries received a grant from The NC State University Foundation to develop our Alt-Textbook project. This program was inspired by similar programs hosted in the Temple University Libraries and University of Massachusetts at Amherst Libraries. Like these programs, NCSU’s Alt-Textbook project provides small grants of between $500 and $2,000 to individual instructors who are willing to replace an existing commercial textbook with an openly licensed or freely available resource. This program solicited proposals from instructors who were interested in developing a new resource, remixing existing resources, or following the open physics textbook model to license a copyrighted resource. A review team comprised of librarians and other campus stakeholders, including a student, a faculty member, representatives from the university Distance Education and Learning Technology Applications office, and a representative from the university Office of Faculty Development, voted on applications and awarded nine grants. This project received press nationally in publications such as Library Journal, and locally, including articles in NC State’s student-run newspaper, The Technician. After the first round of Alt-Textbook grants, our student senate passed a bill stating their support of this program and expressing gratitude to the Libraries.

After the first year, the Alt-Textbook project received internal funding from the NCSU Libraries. Over the course of three years, the Alt-Textbook project has successfully converted 20 courses to using open or free educational resources in place of costly textbooks. NCSU Libraries estimates, based on course enrollment and the cost of the replaced commercial textbooks, that the Alt-Textbook project has saved students nearly $300,000 in textbook costs. This program encouraged the adoption of pre-existing open resources, and sought to engage students in the creation of open resources. These resources have explored innovative instruction such as student made-videos, 3D scan files and renderings, remixed popular articles, interactive tutorials, and iterative courses developed through versioning tools like GitHub. These learning materials are not just free to use, but have added value that is not provided by a print resource.1

As the footprint of Alt-Textbook grew, the Alt-Textbook team of librarians’ contact with students did not always follow suit. This faculty-facing grant program didn’t have obvious opportunities for students to engage. Librarians involved in the Alt-Textbook project focused their advocacy efforts for open textbooks on individual faculty members, departments, and faculty-facing offices or groups on campus. Yet students were an important driving force behind our commitment to textbook affordability. The cost of textbooks affects our students above all, and students have the potential to be the loudest and most persuasive voice in a move towards open education on campus. This chapter discusses the strategies and tactics we took to re-engage our students and empower them to become advocates for open education on campus and beyond.

Getting to Know our Student Community

In order to build connections with our students around open education and open culture, we focused on two approaches: researching the needs of our students through analysis of textbook usage and communication on social media, and interacting with them directly, through existing student groups and with one-on-one conversations. By combining direct engagement with a deeper understanding of student needs, the Libraries have been able to develop partnerships that improved educational outcomes for students.

One of the first steps for our engagement was for us to develop a deeper understanding of student needs and practices related to the assigned learning materials in their courses. Because we could rely on existing research done at the national level related to the financial burden of textbooks, we began our research with a focus on textbook affordability at NCSU. To do this, we analyzed student use of two campus resources: the Libraries textbook lending program and online communities devoted to informal textbook exchange and information sharing. Significant work has been done by groups such as the Student Public Interest Research Group (PIRG) on the needs and practices of students at the national level, but information about the needs of NCSU’s students was limited, and we needed to design engagement activities that would be meaningful and effective at the campus level.

Our textbook lending program has been a significant boon for our students. Because it has been so heavily used, data gathered from the program provided important insights into the needs it was meeting. By tracking student use of the program and cross-referencing it with data from the university bookstore about course size and textbook cost, we were able to use it to identify a large set of granular data that informed our broader understanding of student needs and behaviors (Thompson et al., 2017). This research revealed clear areas where students were relying heavily on textbook lending, either to replace an expensive textbook or to provide access to a book that was physically unavailable or inconvenient to use on campus. Although these areas crossed disciplines and instructors, a clear set of especially high-enrollment courses with expensive assigned textbooks emerged that delineated pain points for students. These specific courses—often, but not always introductory level—clustered around a few discrete areas of study are clearly putting significant financial pressure on our students. By identifying these courses, this research helped us map courses, majors, and communities that were struggling with textbooks and gave us the information to speak credibly about student needs.

This information dovetailed with our second area of research: analysis of informal textbook exchange and information sharing that we have called “student survivalism.” In order to better understand students’ use of informal channels such as social media to share information about courses and develop gray markets for buying and selling used materials, we harvested data representing student activity on an institution-specific Facebook group. We posted a question to an institutional-specific subreddit, and a local online forum, requesting guidance for a new student navigating these issues (Thompson et al., 2017).

This research revealed an impressive community of students engaged in social commerce at NCSU. Students have developed robust markets for buying and selling not only textbooks, but also supplemental materials, from classroom “clickers” and lab kits to forestry vests and handball equipment. Students also use these markets for exchanging materials such as parking passes, loft beds for a dorm room, and, in one case, a bald cap.

In particular, students are using these exchanges to mitigate not only the costs of textbooks, but also to mitigate the challenges created by digital materials that require access codes, which allow access to course materials but which often expire after a single use or remain tied to a single user. In some cases, access code materials were shared in this gray market. Students also used these spaces for information sharing about assigned materials, asking whether they “really need to buy” an expensive textbook or set of materials. This exchange often went further, with discussions about whether a particular instructor was an engaging speaker, whether an elective course was worth enrolling in, and how to navigate their academic career.

Taken together, this research on student survivalism revealed important trends about student needs around the cost of textbooks, but also provided insight into students’ lives on campus. We discovered new things about the way informal channels developed communities of students that offered support and guidance for one another.

The result of all of this research confirmed our sense that students’ engagement with issues of access to resources goes far beyond concerns about open education and the costs of textbooks. Our research reaffirmed that physical, commercial textbooks pose logistical and pedagogical challenges for students. At the same time, student consideration of the value of educational materials goes far beyond the financial costs, leading to questions about how a text fits into a course and whether instructors are thoughtful about their assigned texts. These communities for unmoderated discussion are valuable for students in a variety of ways and point to the potential value of open culture for other aspects of student life. We know students are also creators of scholarly and popular content that benefits from openness. They value communities that connect them to new collaborators and allow them to share their work.

To understand the different ways that open culture resonates with students, we reached out to students directly to understand their perspective and to begin to share the work we had been doing. As the environment of students’ lives and academic work came into view, these conversations illuminated our shared aims: making student work openly available, creating open spaces, and promoting open culture to facilitate collaboration, discovery, and community. These conversations also began to suggest opportunities to work together to meet these aims.

Our first formal work in this space was a series of pop-up interviews done as part of our Open Access Week programming. Held in October 2016, our Open Access Week events included exhibits of open source art, training on use of open scholarly tools, and our “Power of Open” events that connected work in the makerspace with open licensing. Along with these events, we set up a small kiosk in our main library and asked students about their experience with open culture.

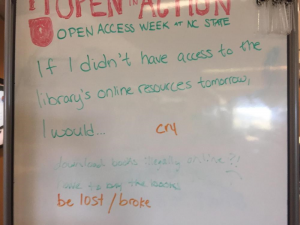

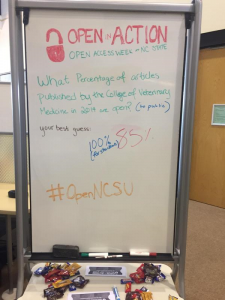

Using a set of simple prompts such as “what percentage of the materials in the library will be available after you graduate?” or “what would you do if you didn’t have access to the library’s databases tomorrow?” we asked students about their information privilege and their experiences with open materials and open culture. As an incentive, we provided candy.

Using a set of simple prompts such as “what percentage of the materials in the library will be available after you graduate?” or “what would you do if you didn’t have access to the library’s databases tomorrow?” we asked students about their information privilege and their experiences with open materials and open culture. As an incentive, we provided candy.

Over the course of the week we spoke to roughly 300 students from across multiple departments and classes. These conversations revealed student interest in open culture on a variety of fronts. Unsurprisingly, many students had little or no awareness of open culture. Since they were unlikely to be familiar with traditional points of references such as open access, students often had, at most, a colloquial understanding of open as “free.” The idea that databases may not be available after graduation took some by surprise. One student, when asked to estimate how much the Libraries paid for a journal subscription guessed “$50.” Responding to questions about how they would cope if licensed resources were suddenly unavailable, students suggested they would “be totally lost” or “cry.” Some students did suggest student survivalism strategies similar to those we examined in our research, such as the student who wrote that they could always “download books illegally online.”

Some students did have familiarity with certain aspects of open culture. For example, students engaged with computer science identified a strong commitment to open source licensing for software. Many students were also familiar with openly licensed resources such as Creative Commons or with gray market sites such as torrents. In many cases, however, this awareness was connected to the idea of free resources, rather than the more robust “5R” understanding of open that librarians and open culture advocates are dedicated to.

The other major takeaway from these pop-up sessions was that there was a desire to learn more and to develop a community. Although students may have been surprised to discover that licensed databases would not be available once they graduated, they wanted to do something about the issue. Naturally, reducing the cost of textbooks resonated particularly deeply, but larger discussions about issues such as public access to scholarship and global access inequity also animated lively discussion. More often than not, students left the pop-up sessions energized about the issues and more aware of the Libraries’ role in addressing them.

We had a similar experience when we reached out to individual students through other contexts. We had productive and exciting discussions with several of our student workers, who often had a better understanding of library resources but still had much to learn about open culture. Conversations with student workers confirmed many of the ideas we identified in pop-up sessions: open was often conflated with “free.” Student workers also confirmed that many students did not understand how open practice was a meaningful advantage for students, especially those who were not planning to become scholars.

As in the pop-ups, however, students were enthusiastic about issues of access and quickly connected them with the value of open as a way to develop communities of practice. Conversations about open access publishing often seemed abstract to these students, but sharing work to develop a portfolio for potential collaborators or employers made sense in a very concrete way. Students were clear that library engagement with open would need to spell out how open culture could make their lives better by finding a job, completing coursework, or identifying new collaborators with shared or complementary interests.

The final group we reached out to was student leaders. The responses from student government representatives and students on campus committees shared many similarities with their fellow students. Knowledge of open culture beyond free resources was scattered across campus and generally tied to the majors or organizations they were engaged with on campus. Even more than their counterparts however, these leaders were enthusiastic about tackling these issues once they understood them. In a few cases, student groups had partnered with the Libraries on small efforts in the past. We were pleasantly surprised to discover that the student senate had passed a resolution commending our Alt-Textbook project several years earlier, although we were a bit puzzled that we had never been made aware of the commendation.

Without exception, committee members were happy to spread the word about Libraries programs. Members of student government immediately pledged to use their offices to help their fellow students and their next question was often “how can we help?” Our job was to find an answer to that question.

Turning Knowledge into Outreach

Armed with a new understanding of how our students understand and approach both textbook affordability and information access, we were ready to find meaningful places to intervene with information about open culture. Our approach centered largely on the idea that, if students could understand the value of openness in the work that they create or are interested in, they could apply this concept to their course materials and become great advocates for open education. This process, which we call “stealth advocacy,” involved identifying pre-existing Libraries or on-campus services that could be enhanced by a conversation about ownership and openness and approaching this service to build a partnership. As a library with an active makerspace community that regularly engages with open source software, open hardware, and openly licensed materials, we chose to integrate this content into pre-existing makerspace instruction.

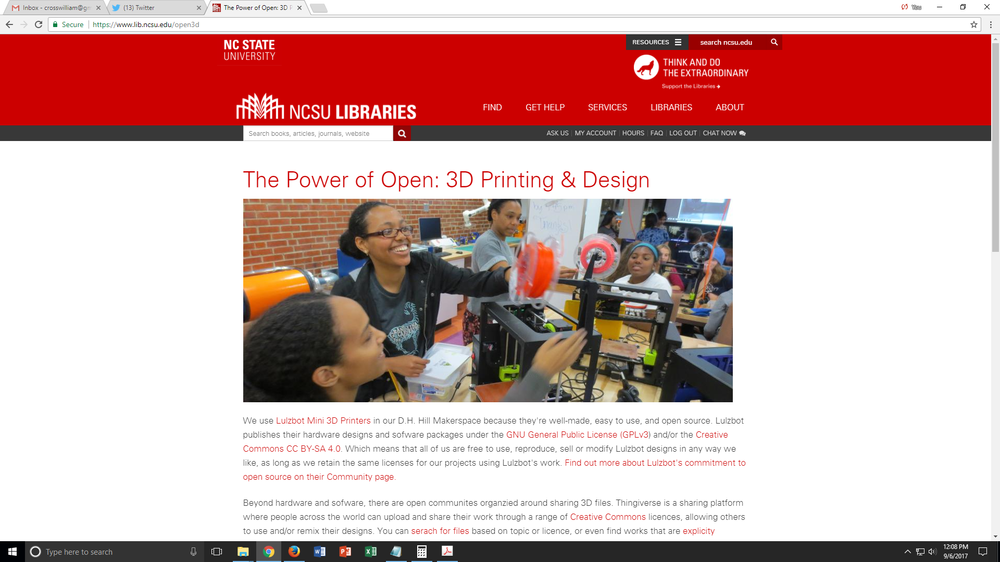

This partnership began as an effort to create local programming for International Open Access Week 2016: Open for Collaboration. We redesigned the curriculum for the existing Arduino and 3D printing workshops for a mini workshop series we called Power of Open. We chose these workshops because existing curriculum required students to engage with open hardware, open source software, and openly licensed materials. The content was designed in a partnership between librarians with tool expertise from the NCSU Libraries’ makerspace and librarians from the NCSU Libraries’ Copyright and Digital Scholarship Center with deep knowledge of copyright, licensing, and the scholarly life cycle. These workshops began with a primer on ownership and licensing, and then delved deeply into hands-on tool training. We taught students how their individual making activity is shaped by a larger community of makers who use open tools and open licensing to enable sharing and community-building and mitigate or eliminate barriers to access.

The Power of Open miniseries drew an engaged audience of faculty, staff, graduate students, and undergraduate students. The feedback was overwhelmingly positive; participants filled out anonymous feedback forms after the session where they were asked to rate the session on a scale of 1 (poor) to 5 (excellent) and all reported the session as a 4 or a 5. Additionally, Harris Kenny, the Vice President of Marketing at Aleph Objects, Inc. maker of the LulzBot desktop 3D printers we used in our workshop, attended the Power of Open: Introduction to 3D Printing and Design workshop. In a letter he wrote about his experience he said, “It is impressive that Lauren and Lillian’s workshop taught foundational lessons about free licensing, copyright, and operating a 3D printer, while providing hands-on experience. The workshop also showed what makes makerspaces so special: bringing the community together.”

After the success of the Power of Open miniseries and the feedback from Harris Kenny, it was clear that this content had the potential to be core to our students’ learning experience. We redesigned the workshops to include content about copyright, licensing, and sharing throughout, and offered them as introductory Arduino and 3D Printing and Design workshops. The new curriculum integrated hands-on activities with the Arduino kits or LulzBot Mini 3D Printers into instruction on open licensing in the making community. For example, in the 3D Printing and Design workshops, after a basic primer on Creative Commons licensing, students were asked to download a CC-licensed remixable file from Thingiverse—a digital repository of files for laser cutting or 3D printing. They then worked with this openly licensed file to remix and print the file. Finally, we discussed what their rights to the remixed file were, and how they might upload or share their altered file or their original design to Thingiverse or a similar repository of openly licensed files. We continued to receive positive feedback on these workshops through our anonymous feedback forms, and many students responded to the question “What was the most useful thing you learned in today’s session?” with a reference to the licensing section of the curriculum. One student even responded, “Copyright – refreshing topic!”

We have continued to take this stealth advocacy approach for the value of open with other workshops offered through the library. In spring 2017, we piloted a workshop for our digital media lab titled “Making Music: Uncovering Copyright.” This workshop was a collaborative effort between NCSU Libraries’ Copyright and Digital Scholarship Center, and the Digital Media Librarian from NCSU Libraries’ Learning Spaces and Services Department. This workshop not only taught students about ownership and licensing in music through hands-on beatmaking and sampling activities, but also pointed students to sources for openly licensed music files, like ccMixter, and platforms which allowed students to upload and openly license their own creations, like SoundCloud. In both of these workshop series, students reported feeling more informed about ownership, and, in multiple cases, feedback forms specifically indicated that students felt the most valuable topic covered was Creative Commons and open licensing. We continue to identify partners with existing information literacy programming where we can find a way to talk about openness to continue to build a community of engaged students that care about open.

We also took a straightforward approach to educating our students about open. In an attempt to connect with motivated students across multiple disciplines and departments, we hosted a full-day student-oriented conference on open culture and open creation. With the support of the Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition (SPARC) and the Right to Research Coalition (R2RC) we applied to host an OpenCon Satellite Event—a local meeting that leverages the momentum of the international OpenCon meeting, designed with the mission of “Empowering the Next Generation to Advance Open Access, Open Education and Open Data.” We hosted this event as part of Open Education Week 2017.

We used the information we had learned through our informational interviews and other information-gathering to design programming that we felt would attract a wide array of students. In addition to bringing in speakers from various library departments, including Collections and Research Strategy, Digital Library Initiatives, and the Copyright and Digital Scholarship Center, we brought in a local open advocate, Tom Callaway. In Tom’s work as the University Outreach Lead for Red Hat, he works to help students and educators understand, use, and contribute to open source efforts. We consulted with the NCSU Center for Student Leadership, Ethics, and Public Service on the design and promotion of the event.

The event was marketed as an opportunity to gain valuable skills for careers in and outside of academia that hinged on openness and leadership. We incentivized students to attend by providing the opportunity for students to create personal web pages and have headshots taken throughout the day. OpenCon 2017: North Carolina Student Leaders saw deep engagement with a group of undergraduate and graduate students from the sciences, social sciences, and humanities to explain the power of openness and open licensing in retaining control of their early work while simultaneously engaging with a broader community of scholars and practitioners. Throughout the day, students engaged with various facets of openness through hands-on tool-based sessions, workshops, and talks with established open advocates. Students received a brief introduction to the concept of openness and how it applies to concepts like education, data, and scholarship. Next, students attended a brief how-to session on openly licensing their own work or identifying and using openly licensed works. Students then had the opportunity to make their own online portfolio using GitHub Pages where they can host a résumé or student work.

Students also had the opportunity to meet Tom Callaway, who has made a career working with open tools and openly licensing his own work. In his keynote address, he told his own story of working on open source and openly licensed projects in his early career and the doors that it opened for him. He also discussed how he values visibility and openness of a candidate’s work when hiring new professionals. Finally, students participated in advocacy training, where they learned how to demonstrate the value of open to key stakeholders, including employers, professors, or administrators. They had the opportunity to practice not only advocating for open, but also explaining why open was important to each student as an individual and as a community member, in small groups. This experience gave students the confidence to speak to those in positions of authority about the importance of openness.

Finally, we reached out to our student senate, the same group that had previously issued a statement in support of Alt-Textbook, about helping us inform students about the services the Copyright & Digital Scholarship Center at the NCSU Libraries could offer. We were able to engage with their President-elect. After a frank conversation with him about the success of Alt-Textbook, the textbook lending program, and the other open programming the libraries supported, we offered our support in any way possible. We invited him to attend OpenCon 2017: North Carolina Student Leaders, and followed up with him specifically about his experience. Our student government has the potential to be the most persuasive body on campus to advocate for open education, and we were willing and eager work with and support students in any way possible. We were invited to the inaugural meeting of the student senate for the 2017–18 academic year and allotted 15 minutes for a presentation.

We led our student senators in a discussion about textbook affordability, prompting them with questions about the cost of their textbooks such as “What is the most expensive textbook you have ever purchased?” and “How many of you have not purchased an assigned textbook? Can you tell us why?” We devoted most of our presentation time to fielding questions, positioning the Libraries as a partner and support on campus, rather than presenting Alt-Textbook as a service offered by the Libraries. It was important that we opened the floor to feedback on our existing services in order to provide room to create a partnership. We spoke candidly to the students about our previous information-gathering conversations as well as the data we had collected about the cost of textbooks on campus. Personalizing and contextualizing the conversation about open education to NCSU’s campus allowed the student senate to connect with the issue.

Shall We Dance? Funneling from “Open” to “OER”

By the summer of 2017, we had developed a two-way relationship between the Libraries and students at NCSU. The Alt-Textbook project is well known, with stories in our student newspaper and student engagement at the individual and student government level. Open is also understood as an integral part of student work in and beyond the classroom. Where there had been so little communication that library resources were unrecognized and a student senate resolution of support went unreported, there was now fertile ground for collaboration.

One of the major results of this new relationship is a fundamental change to our OER program. In its initial form, the Alt-Textbook project was focused primarily on transformative pedagogy, inviting faculty instructors to “do something a textbook can’t!” In collaboration with students, we are reconfiguring the project to reflect the two aims of our work. Instead of asking every project to both save students money and create innovative instruction, we have split our grants into two complementary programs.

Grounded in our discussion with students about immediate, concrete impacts, we offer Student Success grants that save students money. These can be simple adoption of an OER, use of licensed library resources, or any other approach that reduces the burden on students in the current semester.

In order to connect students with the power of open in the larger “5R” sense, we also offer open pedagogy grants that transform teaching and learning. These courses, which replace static, one-size-fits-all materials with shared learning, sustain our efforts to make open a tool to change the environment in the long term. An early partnership with the Wiki Education Foundation provides a promising prototype for these projects. Replacing disposable research assignments that end up in the trash can with research products that contribute to Wikipedia has energized both students and faculty (Jhangiani, 2016; Wiley, 2013). By raising the level of understanding about open culture as a transformative force, we know our students are better prepared to engage with these courses.

In addition to changing the program itself, we have begun to develop strategies that empower students to drive change in open education more broadly. One of our priorities will be to help students tell their stories. We are proud of the advocacy work we have done with faculty and administration, but we recognize that students have a unique perspective that can be a powerful force for change. By raising their awareness of the potential of open culture, we have already seen students make more sophisticated and impactful arguments about open education. Now our role is to amplify those voices and connect them to decision-makers on campus and beyond.

Connecting student voices to faculty is a clear first step. Many faculty are unaware of the burden placed on students by commercial textbooks, and too many more choose to prioritize convenience or even personal financial gain over student success. In the Libraries we have heard and been moved by students’ stories and we aim to give faculty the same chance to hear and react. This is especially true at the departmental level, where engagement with a single faculty member may not be able to change textbook assignments in adjunct-led introductory classes. No amount of faculty outreach can solve this problem, but connecting students in a department with that department’s administration can make a difference.

Student voices can have significant impact on other campus stakeholders such as our campus bookstore. We are fortunate to have a store that is genuinely dedicated to student success and has been a willing partner in our efforts around open education. Nevertheless, decisions made without student input can seem appealing but miss crucial effects that students are best positioned to notice. For example, the recent trend of adopting “inclusive access” models where all students pay a course fee that provides access to course materials may be appealing to a bookstore dazzled by potential savings and the promise of 100 percent sell-through. Our students, however, are often suspicious of the inclusive access model, which they fear will lock them out of long-term access and the ability to avail themselves of the student survivalism skills discussed above. By connecting our students with the bookstore, these concerns can be raised directly so the bookstore is better able to meet its mission and students can be assured their concerns are heard.

We are also committed to giving our students the ability to share their stories beyond campus. Our own advocacy has been strengthened immeasurably by stories from students at other campuses and we need to add our students’ voices to the national conversation. This is particularly true since students benefit so much from hearing from their peers on issues of openness. Trumpeting their success can be an inspiration for students at other campuses. Just as significantly, the quiet communities engaged in student survivalism on individual campuses will be strengthened when connected to a national and global community.

In addition to broadcasting the voices of our students, the Libraries are committed to giving students’ voices greater impact on campus. As frustrating as it was to engage and energize students in our initial pop-ups, only to leave them with nothing to do with that energy, we must provide actionable steps for individual students and the student groups such as student government that want to make a difference. Early efforts in this area have included discussion with student government about naming a student-voted Faculty Champion. We are working to meet stated student demands for early access to course syllabi, as required by the Federal Higher Education Opportunity Act 2008, so they know more about individual courses before they register. If this is successful, we would like to have our course listings indicate which courses have adopted free and open materials so students can vote with their feet. This approach, which empowers students to use their market power to address the imbalance in the textbook market, is especially appealing because it is student- rather than library-driven.

Finally, we are excited about building on our shared commitment to open culture to empower students in other areas. Partnerships with student journals that are published open access and student groups that use open source code for projects have built openness into student lives in ways that are meaningful for them, not just assigned by an instructor or administrator. Engagement with unmediated communication on social media to tell students’ stories and measure the impact of creative works have prepared them for public science and lifelong learning. Use of open platforms like GitHub and Creative Commons have made their works openly available so they can find new collaborators and showcase their work for employers as they move beyond our campus and into the next phase of their lives. As an institution committed to openness, these student benefits also benefit everyone, since a new generation of citizens, artists, and entrepreneurs are conversant with and enthusiastic about open culture.

Conclusion

In one year of open advocacy we have transformed the conversation about openness on campus, and invited our students to not only participate in, but to direct this conversation. However, with the rapid turnover in an undergraduate population at a college or university we must continue to be active in encouraging advocacy. This presents an additional challenge at a large university where you rarely see the same face twice. Working “on student time” means working at a much quicker pace than comes naturally, and it means we need to continually make ourselves, our services, and our accomplishments visible on campus. Though we want to encourage students to be the voice of open education on campus, the Libraries must be diligent in providing support for students to do so.

In the coming academic year, librarians from the Copyright & Digital Scholarship Center, as well as any other librarians invested in open education on campus, must continue to engage face-to-face with students. We must continue to get to know our students as they grow and change, and we must continue to educate our students on the value of openness in education and beyond. The process laid out in this chapter is not linear and finite. Rather, the steps need to be performed continually and in concert.

But now that we have the ear of student leaders, we need to keep them engaged, active, and listening, finding the delicate balance of encouraging students to prioritize open education advocacy while giving students space to advocate in their own voice with their own methods. Our student leaders expressed the need for guidance, support, and leadership with respect to advocacy, which will allow us to be more hands-on. But they have also asserted that NCSU’s campus is unique, and the ways that other student governments on other campuses have promoted open education may not cut and paste easily onto our campus. We must step back and allow students who are in place to represent the student body to decide what will work best for our campus. We plan to stay involved and active in this dialog, as NCSU students push our community to care not only about affordability, but also about openness in scholarship, code, art, and more.

References

Jhangiani, R. (2016, December 7). Ditching the “Disposable assignment” in favor of open pedagogy. Retrieved from osf.io/rc82h

Laster, J. (2010, February 12). North Carolina State U. gives students free access to physics textbook online [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://www.chronicle.com/blogs/wiredcampus/north-carolina-state-u-gives-students-free-access-to-physics-textbook-online/21238

Rashke, G., & Shanks, S. (2012). Water on a hot skillet: Textbooks, open educational resources, and the role of the library. In S. Polanka (Ed.), The no shelf required guide to e-book purchasing from library technology reports (pp. 52–57). Chicago, IL: American Library Association.

Thompson, S., Cross, W., Rigling, L., & Vickery, J. (2017). Data-informed open education advocacy: A new approach to saving students money and backaches. Journal of Access Services,14(3), 118–125. doi:10.1080/15367967.2017.1333911

Wiley, D. (2013, October 21). What is Open Pedagogy? [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://opencontent.org/blog/archives/2975

- See https://www.lib.ncsu.edu/alttextbook/projects for existing Alt-Textbook projects. ↵