11 Student-Driven OER: Championing the Student Voice in Campus-Wide Efforts

Alesha Baker & Cinthya Ippoliti

Introduction

This chapter will discuss how students can actively collaborate with libraries and other campus entities to provide their much-needed perspective, as well as present a case study of how Oklahoma State University (OSU), a public land-grant university, is using student participation to increase campus awareness and provide additional support for the development and implementation of open educational resources (OER). OSU is a research university with high research activity. The total student population at OSU’s primary campus in Stillwater, Oklahoma is approximately 24,000, with an undergraduate population of approximately 20,000. Edmon Low Library is the primary library on campus and is used by undergraduates, graduates, and faculty. Our initial efforts began due to informal interest on the part of a few librarians and has since started to take additional shape and direction as we continue to explore more formalized approaches to integrating OER and discussions about open access in general into campus culture and infrastructure.

Finding the Student Voice

There is a surprising lack of information about how university campuses are including students in the OER conversation, at least on a formal level. A scan of the journal literature indicates that student input is either not included or is not a major factor in decisions surrounding the adoption and use of OER. In order to understand why and how students might be involved in OER efforts, it is important to consider the broader social and pedagogical context in which these efforts might occur. Joyce (2006) states “The prevailing culture in higher education places the responsibility for innovation in the hands of academics, rather than students who may have stronger incentives to experiment with and advance teaching and learning methods” (p. 9).

When an institution decides to adopt an innovation, the institution as a whole and individuals within the institution progress through a complex process. This innovation-decision process includes five stages, (1) knowledge, (2) persuasion, (3) decision, (4) implementation, and (5) confirmation. Those involved in this process make up a social system. Rogers (2003) defines a social system as “a set of interrelated units engaged in joint problem-solving to accomplish a common goal” (p. 23). Students in higher education institutions are included in the social system and should be a considered as part of this process as faculty begins to adopt and use open textbooks. Faculty, students, and all involved in the implementation process collaborate to identify needs and work together to solve problems that arise from the initial identification of the challenges that need to be addressed. According to Rogers, when individuals within a social system can work together, the rate of adoption of an innovation should increase. Ed Hegarty asserts that OER provide a unique opportunity for students to take an active role in their own learning processes in a way that traditional textbooks and pedagogical approaches do not, as he defines an arc-of-life model as “a seamless process that occurs throughout life when participants engage in open and collaborative networks, communities, and openly shared repositories of information in a structured way to create their own culture of learning” (2015, p. 3). He goes on to discuss eight attributes necessary to achieve this type of learning: participatory technologies, people/openness/trust, innovation and creativity, sharing ideas and resources, connected community, learner generated, reflective practice, and peer review (2015, p. 5). By their very nature, OER allow for the type of activities that Hegarty outlines and provide an opportunity for collaboration by helping to shape learner motivation so that the word “open” takes on a much broader meaning than simply available to all: one that invites engagement, reworking, and experimentation from both a learner as well as an instructor perspective. By being able to change the course materials themselves, students are responsible for both the learning experience as well as its application not only throughout the course itself but also in other academic and even professional contexts as students become used to this repurposing of information as a way to help them define and achieve their goals. For example, through open pedagogy, students can modify or create information for wikis, remix audiovisual content, write or revise open textbooks, create and openly license supplemental content to share with their peers, assist in developing test banks, or even create their own course assignments (Hilton & Mason, 2016).

Flavin (2012) offers an interesting perspective on the use of technology and control over the learning process, which can be extrapolated to include the use of OER within the classroom setting. He asserts that “when digital technologies are brought into the classroom setting, the lecturer may have to relinquish some of their authority” (p. 104). While this may seem to disrupt the balance of knowledge, arguably this furthers the notion that students can take control of their learning process by interacting with this open content in a way that makes sense for them, as opposed to being forced to utilize a printed source that may or may not support their educational habits and goals simply because it was simple for the faculty member to adopt. This point is also supported by Shaffer (2014) who mentions that open platforms where students and instructors can pedagogically interact “facilitate student access to existing knowledge, and empower them to critique it, dismantle it, and create new knowledge,” which highlights a two-way experience where both students and instructors can learn from one another.

Finally, in a recent posting on the Open Oregon Educational Resources blog, Lin Hanick and Amy Hofer (2017) discuss how open pedagogy can also influence how librarians teach information literacy. While the discussion of the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) Framework for Information Literacy is beyond the scope of this chapter, it does mention concepts and ideas that are related to OER. Specifically, it states that “open education is simultaneously content and practice” (p. 1) and that by integrating these practices into the classroom, students are learning about issues such as intellectual property, the value of information, and the other costs associated with these “free” resources that they may not be aware of, by acting “like practitioners” (p. 5) where they take on “a disciplinary perspective and engage with a community of practice” (p. 5). These methods have deeply influenced our efforts at OSU, where the Library has taken an active role in soliciting student input as part of all of its services and programs, and OER is no exception. We view the student perspective as central to our efforts and hope to integrate the feedback we receive so that it will inform our outreach efforts as we continue to work with faculty in raising awareness of OER on campus and build on or existing initiatives.

Institutional Context

Our initial efforts began when we received a donation to begin an Open Educational Textbook pilot (http://info.library.okstate.edu/wiseinitiative). The Wise OSU Libraries’ Open Textbook Initiative was made possible through generous initial funding from Dr. James Wise, an OSU alumnus who is a member of the Friends of the Library Board. Dr. Wise has supported a wide variety of library projects over the years, most of them focusing on innovation and technology. The goal of the Wise OSU Libraries’ Open Textbook Initiative is to encourage faculty by providing a stipend for OER adoption or creation to consider open textbooks as less costly alternatives for their students. The types of materials that could qualify for the open textbook project can include material from different media—articles, audio, video, websites—or the use of an existing open access textbook. While some entities that are developing or funding the development of OER focus on high- enrollment courses, OSU encourages faculty in all areas and at all levels to consider using an open textbook. The project is open to either individual faculty members or a group of faculty members teaching multiple sections of the same course (in the case of partnered projects, the monetary award goes to a single representative of the group). A major goal of the open textbook project is to demonstrate how savings may be achieved for students while maintaining or improving the quality of their learning process.

To assist with some of this work, we have developed our own publication platform, dubbed the OSU Libraries ePress (site is in progress), which has allowed us to begin developing workflows for how these manuscripts are copy edited and transformed into their respective epub and PDF formats. In addition, we are offering a more interactive WordPress option for those faculty who are interested in being able to make ongoing changes to their materials and take advantage of the platform’s features. To date, seven faculty members have applied, and each project is in various stages of development.

- LSB 3010/5010: Patent Law and Managing Investments in Technology

- ENGL 1123: International Composition

- EDTC 5030: Learning in a Digital World

- EDTC 5203: Foundations of Educational Technology

- SOIL 4683: Soil, Water, and Weather

- POLS 3103: Introduction to Political Inquiry

- PHIL 1313: Logic and Critical Thinking

Open Pedagogy Project

One of the first courses to develop an OER was EDTC 5030: Learning in a Digital World. In order to accomplish this task, the faculty member reached out to graduate students asking if they would be willing to contribute to its creation; 15 students agreed to help. The student writers began this collaborative effort by selecting a project manager and brainstorming ideas for topics which turned into chapters. The faculty member took the topics to the department faculty to ensure the open textbook would align with the objectives of the program. The focus of the open textbook is learning in a digital world and includes sections such as History and Theory, Digital Literacy, Digital Divide, Pre-K to 12, Adult Learning, Digital Learning Groups, Learning in Emerging Spaces, and Tools and Strategies. Once the topics were agreed upon, the student writers determined which chapters they each would write. After the chapters are written, the student writers and the faculty member will participate in a peer review and editing process. The faculty member’s role is the same as the students’, in that he will be writing and be part of the peer review process. The practice of open pedagogy will continue after the open textbook is used each semester. The students in future sections of EDTC 5053 will have an opportunity to modify or add to the resources through an iterative process with continual input from the students. Students who participate in this Wise initiative by helping write the text for the new open textbooks do not receive monetary compensation, but they do participate in the creation process to gain experience and lend their authors’ voices to the creation of the very tool that will enhance their learning.

Collaborating with students is an important component to the OER initiative. In addition to including students in the creation of OER through open pedagogy, the Library collaborated with an OSU graduate student who was an OER Fellow in the Department of Educational Technology within the College of Education. We were able to hire this student as a graduate research assistant for a semester to assist us with key projects as part of our OER program. The research fellowship was sponsored by the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation and administered by the Open Education Group. The fellowships are meant to encourage research on the cost, outcomes, use, and perceptions of OER. The partnership between OSU and the student led to several exciting initiatives. One activity the student assisted with is co-teaching of workshops. The workshops included educating interested faculty on OER, information on the Wise initiative, and how to get started with finding or writing an open textbook. Through research and the trial of potential platforms and templates, the student provided input on how to progress to the development stage when faculty needed to go beyond the writing or curation of content.

Partnering with other departments and organizations on campus has proven invaluable for developing stronger collaborations and extending the reach of our programs. The Library is in the process of working with the Student Government Association (SGA) to develop joint programming for Open Access Week in fall of 2017. As part of this project, we hope to build on our previous efforts which, though impactful, were one-sided and did not engage students beyond a quick interaction. We hope to co-develop an interactive exhibit during Open Access Week that will serve a dual purpose of informing other students about these resources, as well as give us additional data that we can utilize with campus administration and faculty. This will help drive a more strategic and programmatic approach via our Textbook Affordability Committee and possibly add OER to the campus textbook adoption guidelines that are sent out each year from the Provost’s Office. Although we have not yet discussed the details of what the initiative might encompass, we are confident that with the inroads we have made with the SGA thus far, we will be able to continue collaborating and establishing some concrete action items for fall of this year.

Another partnership which developed and which continues to grow is between the Library and the bookstore as a result of the creation of a textbook affordability program. This partnership is taking a holistic look at options for students, and we are seeing OER being included as part of that suite of materials. Moreover, the Library was recently invited to serve on the Textbook Affordability Committee, and we are optimistic that our inclusion will allow us to take a broad look at how these efforts can be scaled and adapted at a university-wide level. As a small start, the Library collaborated with an economics course in fall of 2016 to survey students about their textbook needs and discovered that over 75 percent would use an OER, and 46 percent would purchase a print copy of an OER textbook and would be willing to pay about $20 for it. This percent is similar to a previous study cited in Hilton and Wiley (2011) that shows 40 percent of students continued to purchase print versions of their required textbooks even when free online copies were available to them. The option of purchasing a print copy is helpful for the students who prefer this format over the digital version alone.

This preliminary research has allowed the Library to work with the bookstore to offer an on-demand printing model via our FedEx office on campus, which gives students the opportunity to print only the sections of an open textbook that they need for a nominal fee of approximately $8 and also allows them to pay for added customization, such as color images and different binding options, depending on their preferences. Anecdotal evidence from the bookstore indicates that students are unwilling to pay $35 for an OpenStax textbook (which had been sitting on their shelves for this course with virtually no demand) simply because they did not need all of it and we hope that this model will encourage students to print what they need. We plan to continue marketing this program campus-wide as we get a better sense of how we can continue campus-wide conversations around these topics.

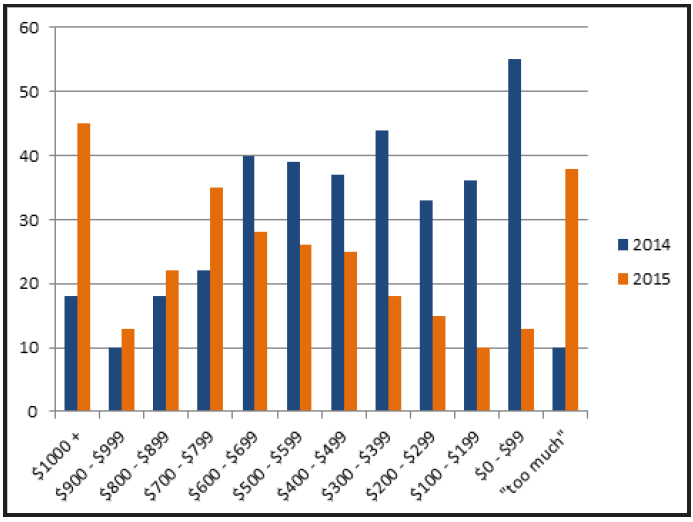

Finally, the Library regularly surveys students about their textbook costs as part of their Open Access Week programming. During Open Textbook Week 2014 and 2015, we set up whiteboards in the south lobby to solicit student feedback/input on the cost of their textbooks with an accompanying table display on open textbooks. Students would stop by, and if they did not ask questions, they often made a hash mark or comment on the whiteboards. There was one constant question: How Much Did Your Textbooks Cost This Year? The second board featured a question that changed every other day:

- What Is Your Most Expensive Textbook?

- For What Class Did You Not Purchase the Textbook, and Why?

The images below detail the presentation as well as the responses from students that we compiled during each of these sessions. This information has allowed us to gather some informal evidence for our campus which has supported national trends and which continues to lend the student perspective to these issues especially as we determine ways we can continue working with campus administration to make our efforts more visible and impactful.

While we have covered some ground through these initial efforts, we recognize that there is much that still needs to be done. We would like to scale up the pilot into a full-blown program, where we receive proposals on an ongoing basis that are reviewed by a formal board comprised of campus faculty and students. This would allow us to develop a more cohesive workflow for the entire process from the initial idea all the way to the published product and its integration within the curriculum. This model will require significant effort on our part to develop an outreach and marketing program, as well as further develop the underlying infrastructure so that authors are fully supported throughout the duration of the project and the implementation of the resource. We would also like to include these OER into our institutional repository as a way to make them even more discoverable, and also to highlight these works as part of the university’s scholarly output. In addition to the board, we hope to partner with our Technical Writing Program where students can act as copy editors and gain professional experience while helping us in an area where the Library might not have sufficient expertise.

Finally, we plan to develop a survey to gather baseline information about students’ perception of their learning and overall course experience using these resources. This will most likely take the form of a brief online survey where we hope to find out how many students accessed the books, how many printed them versus downloaded them. We would also like to find out specifically what they thought of the format of these texts, and ask them for ways that we can improve their discoverability, accessibility, and overall functionality. We hope this will allow us to pave the way for a more robust assessment model once we have additional projects under our belt. Ideally, we would like to conduct some comparative analysis using faculty anecdotal data where we can determine how the quality of the learning was impacted by these resources.

Tips for Engaging Students at Your Institution

It is important to include student input into any OER initiative to maximize the chances of success. Although adding a student voice to library efforts does not guarantee success, it helps lend an added element of support that might sway other stakeholders, such as university administration and faculty, to listen where they might not have before. A formal needs assessment might help pave the way for some of these discussions and secure additional buy-in from students and student groups. There are many different ways to go about this, and the University of Idaho Extension program details the most commonly used methods in a concise and useful fashion. The main elements of any needs assessment consist of the following steps (McCawley, 2009):

- What is it that you want to learn from the needs assessment?

- Who is the target audience? Whose needs are you measuring, and to whom will you give the information?

- How will you collect data that will tell you what you need to know? Will you collect data directly from the target audience or indirectly?

- How will you select a sample of respondents who represent the target audience?

- What instruments and techniques will you use to collect data?

- How will you analyze the data you collect?

- What will you do with the information that you gather?

An important point to consider about this type of assessment is to include information about student needs that go beyond content. For example, based on OSU’s modest survey, we were able to determine that students just wanted to pay for the content they needed and were not interested in an entire textbook, even if it was fully bound and in color. They were more likely to choose a “stripped down” bound version in black and white if it meant they would get the information they had to have and nothing extraneous. Without asking students what they preferred, we might have made some erroneous assumptions about their desire to have better looking, yet less useful, versions of their textbook, when in fact that was not the case.

Another important step is to reach out to student organizations such as governing bodies, resident life, and Greek organizations. This approach is a more effective and scalable than trying to target individuals, and it can result in a broader reach. The good news is that this issue should be a fairly simple one to address with these groups because OER benefit students directly. The question then becomes one of execution. Establishing a clear yet flexible plan will allow these organizations to determine how they would like to move forward. In the case of OSU for example, we are discussing both developing some shared programming as well as approaching faculty members directly about the use of OER in their high- enrollment courses.

Using some of the evidence you have gathered (such as the statistics above, for example) will also help lend more weight to your arguments and proposed planning, and if they are collected by students at your institution and shared through those same students, they will have a much stronger impact than simply citing statistics that may or may not provide enough compelling evidence about how these costs are affecting local populations. Also, student groups can assist with marketing and outreach efforts and can go with you when you make visits to faculty or talk with administrators. They can actively participate in any open access programming that is held on campus, and it is up to you to ensure that for every faculty panel or participant, students have an equally strong presence to keep momentum going and serve as a reminder of the purpose of championing OER. Crafting a uniform and consistent message will ensure that everyone is working towards a unified goal.

Finally, plan for success by establishing a committee or taskforce comprised of library, faculty, student, and other campus representatives, to look at these issues at a strategic level. Ensuring that students are invited to the table as part of this work will not only signal that their feedback is valued, but can also help shape how these resources are developed, implemented, and assessed as part of an overall program. Thinking about both in-class as well as out-of-class elements should provide a holistic picture of how these resources are integrated and utilized throughout the entire student experience. The former may require collaborations with the campus institute for teaching and learning and the faculty council. This will prevent pedagogical considerations that are implemented from being seen as trying to usurp existing processes for how faculty modify their curriculum, especially since open pedagogy practices can require what some may see as a radical shift in teaching habits and approaches. This work could necessitate additional training for faculty in working with students in a more collaborative capacity than they might have previously done, and might require additional practice with assessing and grading the types of artifacts that would emerge.

This might be met with significant resistance and necessitate having involvement from a higher administrative capacity in order to pave the way for pilots and other smaller-scale implementations before a broader open access program is announced, but having a group that is focused on these issues should help you anticipate and resolve these types of challenges as they arise. This more expansive approach can help shift the focus away from objections related to publisher kickbacks and long-held preconceptions about these resources, because they are furthering student learning and success which is everyone’s ultimate goal.

Conclusion

There is no magic formula when it comes to championing campus-wide OER efforts, and as we have explored throughout this chapter, there are several ways in which students can become active participants both in and out of the classroom. One of the most important lessons to be taken away from these conversations is that of providing opportunities for faculty and students alike to engage in the types of pedagogical and programmatic activities that allow for deeper collaboration and re-imagining of both the learning process as well as the content itself. This is not an easy thing to accomplish, as there are decades of preconceived notions, habits, and practices in existence on both sides, but the library can provide a platform where new projects and initiatives have an opportunity to be explored and become successful as we continue on the path to redefining the way in which OER influence the world of higher education and beyond.

References

Flavin, M. (2012). Disruptive technologies in higher education. Presented at the Annual Conference of the Association for Learning Technology, London, UK.

Hanick, S., & Hofer, A. (2017, May 31). Opening the framework: Connecting open education practices and information literacy [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://openoregon.org/opening-the-framework/

Hegarty, B. (2015). Attributes of open pedagogy: A model for using open educational resources. Education Technology, 4. Retrieved from https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/ca/Ed_Tech_Hegarty_2015_article_attributes_of_open_pedagogy.pdf

Hilton, J. L., III, & Mason, S. (2016). Open pedagogy library. Retrieved from http://openedgroup.org/openpedagogy

Hilton J. L., III, & Wiley, D. (2011). Open access textbooks and financial sustainability: A case study on Flat World Knowledge. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 12(5), 18–26.

Joyce, A. (2006). OECD study of OER: Forum report. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Alexa_Joyce2/publication/265183257_OECD_study_of_OER_forum_report/links/564b064e08ae9cd9c827cf5a.pdf

McCawley, P. F. (2009). Methods for conducting an educational needs assessment. University of Idaho, 23.

Open Education Group (2017). Open education library. Retrieved from http://openedgroup.org/openpedagogy

Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). New York: The Free Press.

Senack, E. (2014). Fixing the broken textbook market: How students respond to high textbook costs and demand alternatives. US Public Interest Research Group & Student PIRGS. Retrieved from http://www.uspirg.org/sites/pirg/files/reports/NATIONAL%20Fixing%20Broken%20Textbooks%20Report1.pdf

Shaffer, K. (2014). The Critical Textbook. Hybrid Pedagogy. Retrieved from http://hybridpedagogy.org/critical-textbook/

Wiley, D. (2014, March 5). The access compromise and the 5th R [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://opencontent.org/blog/archives/3221