Mosquitoes

For this discussion, we will be looking at the controversy surrounding the use of Naled to control for adult mosquitos. You will read an article on the topic, and then you will compose a post in which you take a position on its use. You will then share your position with your group.

Pre-Discussion Work

To begin this assignment, review the following resource, which is located in the reading section of Topic 3:

Drafting Your Response

Next, prepare your forum post by creating a Google document. On your document, answer the following questions:

- Is it appropriate to use the aerial-sprayed chemical Nalen to fight mosquito populations in the face of the public health risk posed by the Zika virus? Take a position and explain why.

Be sure to support your responses by referencing materials from this module. Also, once you have answered the questions, be sure to proofread what you wrote before you share it.

Discussing Your Work

To discuss your findings, follow the steps below:

Step 01. After you have finished writing and proofreading your response, click on the link to your group under the My Groups link in the main menu on the left side of this page.

Step 02. Once in your group, click on the Group Discussion Board link and locate the Module 02 Discussion Forum 2.

Step 03. In the Module 02 Discussion Forum 2, create a new thread and title it using the following format: Yourname’s Position on the Use of Nalen.

Step 04. In the Message field of your post, copy and paste the text of your composition from the Google Document you created– please do not provide a link to that Google Doc.

Step 05. Correct the formatting using the text-editing tools in the Message field. Add bolding, underlining, or italics where necessary. Also, correct any spacing and other formatting issues. Make sure your post looks professional.

Step 06. When you have completed proofreading and fixing your post formatting, click on the Submit button.

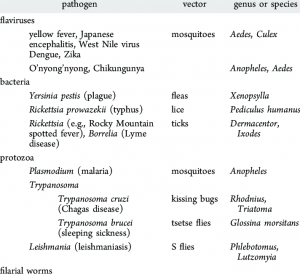

Mosquito-borne diseases are those spread by the bite of an infected mosquito. Diseases that are spread to people by mosquitoes include Zika virus, West Nile virus, Chikungunya virus, dengue, and malaria.

Employers should protect workers and workers should protect themselves from diseases spread by mosquitoes. Although people may not become sick after a bite from an infected mosquito, some people have a mild, short-term illness or (rarely) severe or long-term illness. Severe cases of mosquito-borne diseases can cause death.

The following is a partial list of mosquito borne diseases in the United States. For a complete list refer to NIOSH Mosquito Borne Disease For a listing of Worldwide Mosquito borne diseases see WHO Vector Borne Disease.

Chikungunya virus is spread to people by the bite of an infected mosquito. The most common symptoms of infection are fever and joint pain. Other symptoms may include headache, muscle pain, joint swelling, or rash. Outbreaks have occurred in countries in Africa, Americas, Asia, Europe, and the Caribbean, Indian and Pacific Oceans. There is a risk the virus will be spread to unaffected areas by infected travelers. There is currently no vaccine to prevent or medicine to treat chikungunya virus infection. Travelers can protect themselves by preventing mosquito bites. When traveling to countries with chikungunya virus, use insect repellent; wear long-sleeved shirts and pants; and stay in places with air conditioning or that use window and door screens.

Dengue viruses are spread to people through the bite of an infected Aedes species (Ae. aegypti or Ae. albopictus) mosquito. Almost half of the world’s population, about 4 billion people, live in areas with a risk of dengue. Dengue is often a leading cause of illness in areas with risk.

- 1 in 4: About one in four people infected with dengue will get sick.

- For people who get sick with dengue, symptoms can be mild or severe.

- Severe dengue can be life-threatening within a few hours and often requires care at a hospital.

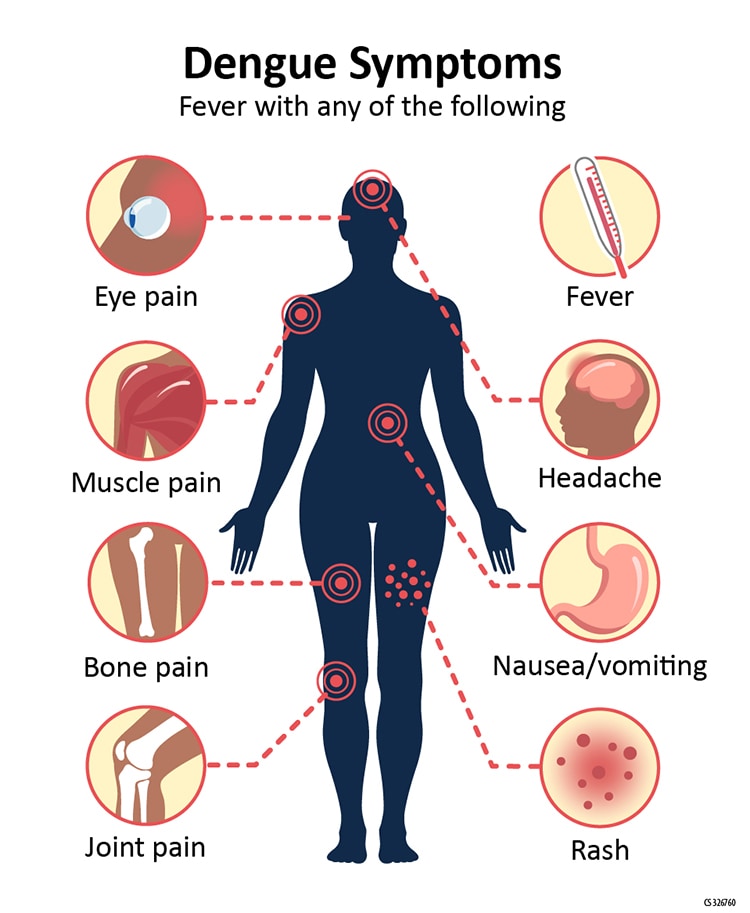

Symptoms

- Mild symptoms of dengue can be confused with other illnesses that cause fever, aches and pains, or a rash.

The most common symptom of dengue is fever with any of the following:

- Nausea, vomiting

- Rash

- Aches and pains (eye pain, typically behind the eyes, muscle, joint, or bone pain)

- Any warning sign

Symptoms of dengue typically last 2–7 days. Most people will recover after about a week.

Malaria is a mosquito-borne disease caused by a parasite. People with malaria often experience fever, chills, and flu-like illness. Left untreated, they may develop severe complications and die. In 2020 an estimated 241 million cases of malaria occurred worldwide and 627,000 people died, mostly children in sub-Saharan Africa. About 2,000 cases of malaria are diagnosed in the United States each year. The vast majority of cases in the United States are in travelers and immigrants returning from countries where malaria transmission occurs, many from sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia.

Malaria is a serious and sometimes fatal disease caused by a parasite that commonly infects a certain type of mosquito which feeds on humans. People who get malaria are typically very sick with high fevers, shaking chills, and flu-like illness. Although malaria can be a deadly disease, illness and death from malaria can usually be prevented.

About 2,000 cases of malaria are diagnosed in the United States each year. The vast majority of cases in the United States are in travelers and immigrants returning from countries where malaria transmission occurs, many from sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia.

Lifecycle

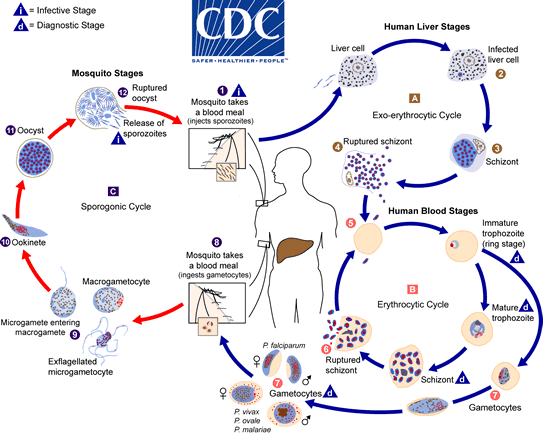

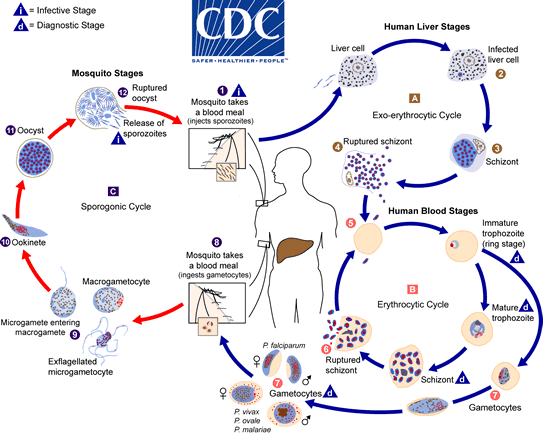

The natural history of malaria involves cyclical infection of humans and female Anopheles mosquitoes. In humans, the parasites grow and multiply first in the liver cells and then in the red cells of the blood. In the blood, successive broods of parasites grow inside the red cells and destroy them, releasing daughter parasites (“merozoites”) that continue the cycle by invading other red cells.

The blood stage parasites are those that cause the symptoms of malaria. When certain forms of blood stage parasites (gametocytes, which occur in male and female forms) are ingested during blood feeding by a female Anopheles mosquito, they mate in the gut of the mosquito and begin a cycle of growth and multiplication in the mosquito. After 10-18 days, a form of the parasite called a sporozoite migrates to the mosquito’s salivary glands. When the Anopheles mosquito takes a blood meal on another human, anticoagulant saliva is injected together with the sporozoites, which migrate to the liver, thereby beginning a new cycle.

Thus the infected mosquito carries the disease from one human to another (acting as a “vector”), while infected humans transmit the parasite to the mosquito, In contrast to the human host, the mosquito vector does not suffer from the presence of the parasites.

The malaria parasite life cycle involves two hosts. During a blood meal, a malaria-infected female Anopheles mosquito inoculates sporozoites into the human host  . Sporozoites infect liver cells

. Sporozoites infect liver cells  and mature into schizonts

and mature into schizonts  , which rupture and release merozoites

, which rupture and release merozoites  . (Of note, in P. vivax and P. ovale a dormant stage [hypnozoites] can persist in the liver (if untreated) and cause relapses by invading the bloodstream weeks, or even years later.) After this initial replication in the liver (exo-erythrocytic schizogony

. (Of note, in P. vivax and P. ovale a dormant stage [hypnozoites] can persist in the liver (if untreated) and cause relapses by invading the bloodstream weeks, or even years later.) After this initial replication in the liver (exo-erythrocytic schizogony  ), the parasites undergo asexual multiplication in the erythrocytes (erythrocytic schizogony

), the parasites undergo asexual multiplication in the erythrocytes (erythrocytic schizogony  ). Merozoites infect red blood cells

). Merozoites infect red blood cells  . The ring stage trophozoites mature into schizonts, which rupture releasing merozoites

. The ring stage trophozoites mature into schizonts, which rupture releasing merozoites  . Some parasites differentiate into sexual erythrocytic stages (gametocytes)

. Some parasites differentiate into sexual erythrocytic stages (gametocytes)  . Blood stage parasites are responsible for the clinical manifestations of the disease. The gametocytes, male (microgametocytes) and female (macrogametocytes), are ingested by an Anopheles mosquito during a blood meal

. Blood stage parasites are responsible for the clinical manifestations of the disease. The gametocytes, male (microgametocytes) and female (macrogametocytes), are ingested by an Anopheles mosquito during a blood meal  . The parasites’ multiplication in the mosquito is known as the sporogonic cycle

. The parasites’ multiplication in the mosquito is known as the sporogonic cycle  . While in the mosquito’s stomach, the microgametes penetrate the macrogametes generating zygotes

. While in the mosquito’s stomach, the microgametes penetrate the macrogametes generating zygotes  . The zygotes in turn become motile and elongated (ookinetes)

. The zygotes in turn become motile and elongated (ookinetes)  which invade the midgut wall of the mosquito where they develop into oocysts

which invade the midgut wall of the mosquito where they develop into oocysts  . The oocysts grow, rupture, and release sporozoites

. The oocysts grow, rupture, and release sporozoites , which make their way to the mosquito’s salivary glands. Inoculation of the sporozoites

, which make their way to the mosquito’s salivary glands. Inoculation of the sporozoites  into a new human host perpetuates the malaria life cycle.

into a new human host perpetuates the malaria life cycle.

Malaria Transmission in the United States

Mosquito-Borne Malaria

Outbreaks of locally transmitted cases of malaria in the United States have been small and relatively isolated, but the potential risk for the disease to re-emerge is present due to the abundance of competent vectors, especially in the southern states. At the request of the states, CDC assists in these investigations of locally transmitted mosquito-borne malaria.

“Airport” malaria refers to malaria caused by infected mosquitoes that are transported rapidly by aircraft from a malaria-endemic country to a non-endemic country. If the local conditions allow their survival upon arrival, they can potentially bite local residents who can thus acquire malaria without having traveled abroad. Airport transmitted malaria is challenging to confirm, but can be considered after exclusion of other likely explanations.

In congenital malaria, infected mothers transmit parasites to their child during pregnancy before or during delivery. Therefore, though congenital transmission is rare, health-care providers should be alert to the diagnosis of malaria in ill neonates and young infants, particularly those with fever.

During evaluation, health-care providers should obtain a complete and accurate travel and residency history on the patient and close relatives. Patients should be asked about transfusion of blood products.

The absence of recent foreign travel or a long interval between immigration of the mother and the birth of the infant being examined should not discourage clinicians from obtaining blood films on the patient to rule out a potentially life-threatening but treatable infection.

Transfusion-transmitted malaria is rare in the United States, but it is a potential severe complication in blood recipients. On average, only one case of transfusion-transmitted malaria occurs in the United States every 2 years.

Because no approved tests are available in the United States to screen donated blood for malaria, prevention of transfusion-transmitted malaria requires careful questioning of prospective donors.

Yellow Fever

The yellow fever virus is found in tropical and subtropical areas of Africa and South America. The virus is spread to people by the bite of an infected mosquito. Yellow fever is a very rare cause of illness in U.S. travelers. Illness ranges from a fever with aches and pains to severe liver disease with bleeding and yellowing skin (jaundice). Yellow fever infection is diagnosed based on laboratory testing, a person’s symptoms, and travel history. There is no medicine to treat or cure infection. To prevent getting sick from yellow fever, use insect repellent, wear long-sleeved shirts and long pants, and get vaccinated.

The majority of people infected with yellow fever virus will either not have symptoms, or have mild symptoms and completely recover.

For people who develop symptoms, the time from infection until illness is typically 3 to 6 days.

Because there is a risk of severe disease, all people who develop symptoms of yellow fever after traveling to or living in an area at risk for the virus should see their healthcare provider. Once you have been infected, you are likely to be protected from future infections.

Symptoms

- Most people will not have symptoms.

- Some people will develop yellow fever illness with initial symptoms including:

- Sudden onset of fever

- Chills

- Severe headache

- Back pain

- General body aches

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Fatigue (feeling tired)

- Weakness

- Most people with the initial symptoms improve within one week.

- For some people who recover, weakness and fatigue (feeling tired) might last several months.

- A few people will develop a more severe form of the disease.

- For 1 out of 7 people who have the initial symptoms, there will be a brief remission (a time you feel better) that may last only a few hours or for a day, followed by a more severe form of the disease.

- Severe symptoms include:

- High fever

- Yellow skin (jaundice)

- Bleeding

- Shock

- Organ failure

- Severe yellow fever disease can be deadly. If you develop any of these symptoms, see a healthcare provider immediately.

- Among those who develop severe disease, 30-60% die.

Transmission of Yellow Fever Virus

Yellow fever virus is an RNA virus that belongs to the genus Flavivirus. It is related to West Nile, St. Louis encephalitis, and Japanese encephalitis viruses. Yellow fever virus is transmitted to people primarily through the bite of infected Aedes or Haemagogus species mosquitoes. Mosquitoes acquire the virus by feeding on infected primates (human or non-human) and then can transmit the virus to other primates (human or non-human). People infected with yellow fever virus are infectious to mosquitoes (referred to as being “viremic”) shortly before the onset of fever and up to 5 days after onset.

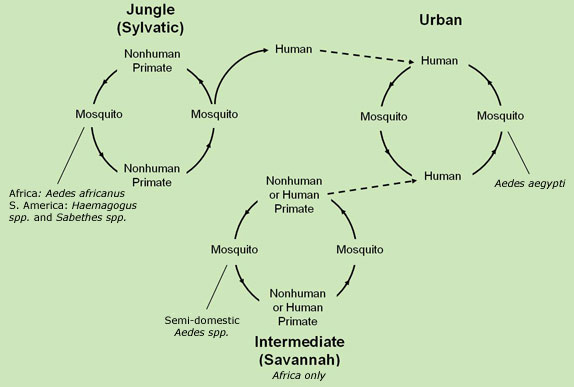

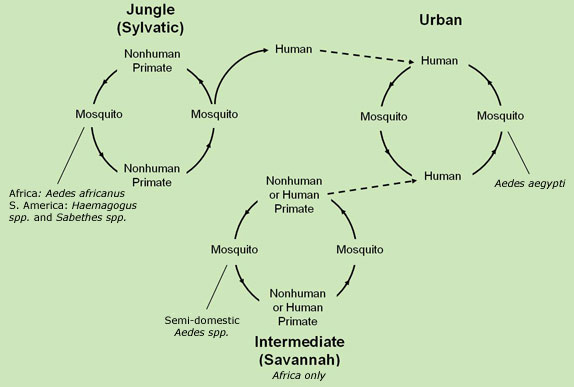

Yellow fever virus has three transmission cycles: jungle (sylvatic), intermediate (savannah), and urban.

- The jungle (sylvatic) cycle involves transmission of the virus between non-human primates (e.g., monkeys) and mosquito species found in the forest canopy. The virus is transmitted by mosquitoes from monkeys to humans when humans are visiting or working in the jungle.

- In Africa, an intermediate (savannah) cycle exists that involves transmission of virus from mosquitoes to humans living or working in jungle border areas. In this cycle, the virus can be transmitted from monkey to human or from human to human via mosquitoes.

- The urban cycle involves transmission of the virus between humans and urban mosquitoes, primarily Aedes aegypti. The virus is usually brought to the urban setting by a viremic human who was infected in the jungle or savannah.

A safe and effective yellow fever vaccine has been available for more than 80 years.

- A single dose provides lifelong protection for most people.

- The vaccine is a live, weakened form of the virus given as a single shot.

- Vaccine is recommended for people aged 9 months or older and who are traveling to or living in areas at risk for yellow fever virus in Africa and South America.

- Yellow fever vaccine may be required for entry into certain countries.

Fleas

Fleaborne Diseases of the United States

In the United States, some fleas carry pathogens that can cause human disease, including:

Plague — most commonly transmitted to humans in the United States by infected ground squirrel fleas, Oropsylla montana, and globally by infected Oriental rat fleas, Xenopsylla cheopis. Also, may be transmitted by improperly handling an animal infected with plague bacteria. Most U.S. cases occur in rural areas of the western United States.

Plague is a disease that affects humans and other mammals. It is caused by the bacterium, Yersinia pestis. Humans usually get plague after being bitten by a rodent flea that is carrying the plague bacterium or by handling an animal infected with plague. Plague is infamous for killing millions of people in Europe during the Middle Ages. Today, modern antibiotics are effective in treating plague. Without prompt treatment, the disease can cause serious illness or death. Presently, human plague infections continue to occur in rural areas in the western United States, but significantly more cases occur in parts of Africa and Asia.

The bacteria that cause plague, Yersinia pestis, maintain their existence in a cycle involving rodents and their fleas. Plague occurs in rural and semi-rural areas of the western United States, primarily in semi-arid upland forests and grasslands where many types of rodent species can be involved. Many types of animals, such as rock squirrels, wood rats, ground squirrels, prairie dogs, chipmunks, mice, voles, and rabbits can be affected by plague. Wild carnivores can become infected by eating other infected animals.

Scientists think that plague bacteria circulate at low rates within populations of certain rodents without causing excessive rodent die-off. These infected animals and their fleas serve as long-term reservoirs for the bacteria. This is called the enzootic cycle.

Occasionally, other species become infected, causing an outbreak among animals, called an epizootic. Humans are usually more at risk during, or shortly after, a plague epizootic. Scientific studies have suggested that epizootics in the southwestern United States are more likely during cooler summers that follow wet winters. Epizootics are most likely in areas with multiple types of rodents living in high densities and in diverse habitats.

In parts of the developing world, plague can sometimes occur in urban areas with dense rat infestations. The last urban outbreak of rat-associated plague in the United States occurred in Los Angeles in 1924-1925.

Flea-borne (murine) typhus — transmitted to people by infected cat fleas, Ctenocephalides felis, infected Oriental rat fleas, Xenospylla cheopis, or their feces (poop; also called “flea dirt”). Most cases in the United States are reported from California, Texas, and Hawaii.

Flea-borne (murine) typhus, is a disease caused by a bacteria called Rickettsia typhi. Flea-borne typhus is spread to people through contact with infected fleas. Fleas become infected when they bite infected animals, such as rats, cats, or opossums. When an infected flea bites a person or animal, the bite breaks the skin, causing a wound. Fleas poop when they feed. The poop (also called flea dirt) can then be rubbed into the bite wound or other wounds causing infection. People can also breathe in infected flea dirt or rub it into their eyes. This bacteria is not spread from person to person. Flea-borne typhus occurs in tropical and subtropical climates around the world including areas of the United States (southern California, Hawaii, and Texas). Flea-borne typhus is a rare disease in the United States.

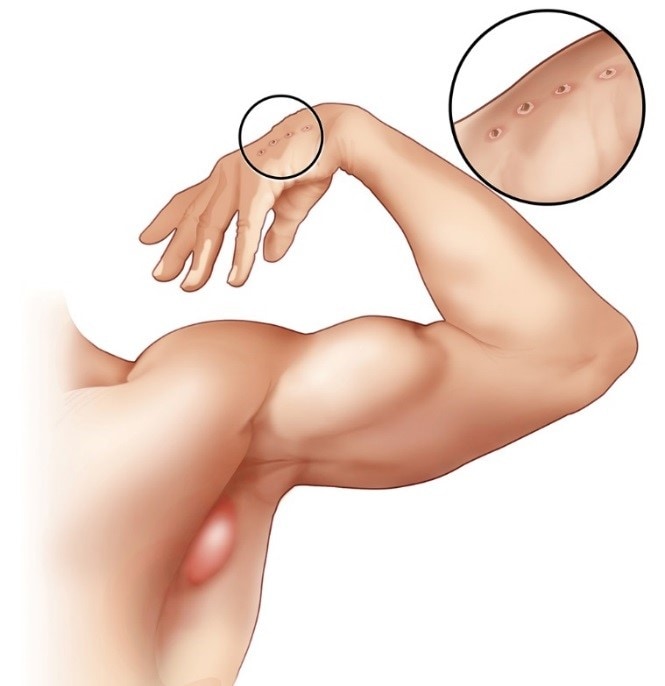

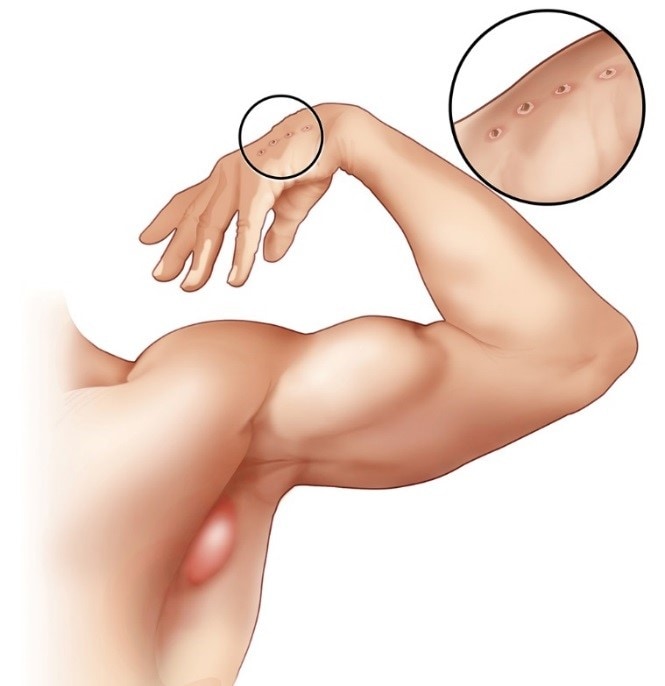

Cat scratch disease (CSD) — transmitted to humans most often after a scratch from a domestic or feral cat that has been infected by a Ctenocephalides felis flea, or through flea feces (poop; also called “flea dirt”) being inoculated through a cat scratch. CSD occurs wherever cats and fleas are found.

Swollen lymph node in armpit and cat scratch on hand

CSD is a bacterial infection caused by Bartonella henselae. Most infections usually occur after scratches from domestic or feral cats, especially kittens. CSD occurs wherever cats and fleas are found. The most common symptoms include:

- Fever

- Enlarged, tender lymph nodes that develop 1–3 weeks after exposure

- A scab or pustule at the scratch site

In the United States, most cases of CSD occur in the fall and winter. Illness is most common in children under the age of 15.

Fleaborne parasites, such as tapeworms can spread to people and animals if they accidentally swallow an infected flea. Small children are at a higher risk than adults, as they may spend more time close to the floor and carpeted areas where fleas are found. Most infected people will not show symptoms and will not know they are carrying tapeworms.

Ticks

Tick exposure can occur year-round, but ticks are most active during warmer months (April-September). Know which ticks are most common in your area.

This is a Dermacentor andersoni hard tick common to Idaho

Selected Tick Borne Diseases – Not a comprehensive list. A complete list is on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website at Diseases Transmitted by Ticks

Lyme disease is transmitted by the blacklegged tick (Ixodes scapularis) in the northeastern U.S. and upper midwestern U.S. and the western blacklegged tick (Ixodes pacificus) along the Pacific coast.

Lyme disease is the most common vector-borne disease in the United States. Lyme disease is caused by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi and rarely, Borrelia mayonii. It is transmitted to humans through the bite of infected blacklegged ticks. Typical symptoms include fever, headache, fatigue, and a characteristic skin rash called erythema migrans. If left untreated, infection can spread to joints, the heart, and the nervous system. Lyme disease is diagnosed based on symptoms, physical findings (e.g., rash), and the possibility of exposure to infected ticks. Laboratory testing is helpful if used correctly and performed with validated methods. Most cases of Lyme disease can be treated successfully with a few weeks of antibiotics. Steps to prevent Lyme disease include using insect repellent, removing ticks promptly, applying pesticides, and reducing tick habitat. The ticks that transmit Lyme disease can occasionally transmit other tickborne diseases as well.

Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) is transmitted by the American dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis), Rocky Mountain wood tick (Dermacentor andersoni), and the brown dog tick (Rhipicephalus sangunineus) in the U.S. The brown dog tick and other tick species are associated with RMSF in Central and South America.

Early signs and symptoms are not specific to RMSF (including fever and headache). However, the disease can rapidly progress to a serious and life-threatening illness. See your healthcare provider if you become ill after having been bitten by a tick or having been in the woods or in areas with high brush where ticks commonly live.

Signs and symptoms can include:

- Fever

- Headache

- Rash

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Stomach pain

- Muscle pain

- Lack of appetite

Rash

Figure 1. Late stage rash in a patient with Rocky Mountain spotted fever.

Rash is a common sign in people who are sick with RMSF. Rash usually develops 2-4 days after fever begins. The look of the rash can vary widely over the course of illness. Some rashes can look like red splotches and some look like pinpoint dots. While almost all patients with RMSF will develop a rash, it often does not appear early in illness, which can make RMSF difficult to diagnose.

Long-term Health Problems

- RMSF does not result in chronic or persistent infections.

- Some patients who recover from severe RMSF may be left with permanent damage, including amputation of arms, legs, fingers, or toes (from damage to blood vessels in these areas); hearing loss; paralysis; or mental disability. Any permanent damage is caused by the acute illness and does not result from a chronic infection.

Tickborne relapsing fever (TBRF) is transmitted to humans through the bite of infected soft ticks. TBRF has been reported in 15 states: Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Kansas, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Texas, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming and is associated with sleeping in rustic cabins and vacation homes.

Relapsing fever is bacterial infection that can cause recurring bouts of fever, headache, muscle and joint aches, and nausea. There are three types of relapsing fever:

- Tick-borne relapsing fever (TBRF)

- Louse-borne relapsing fever (LBRF)

- Borrelia miyamotoi disease (sometimes called hard tick relapsing fever)

TBRF occurs in the western United States and is usually linked to sleeping in rustic, rodent-infested cabins in the mountains. In Texas, TBRF is frequently linked to cave exposures. LBRF is transmitted by the human body louse and usually occurs in refugee settings in developing parts of the world. Borrelia miyamotoi disease occurs in the same places where Lyme disease is found and is transmitted by the blacklegged tick.

Tick-borne relapsing fever (TBRF) is a rare infection linked to sleeping in rustic cabins, particularly cabins in mountainous areas of the western United States. The main symptoms of TBRF are high fever (e.g., 103° F), headache, muscle and joint aches. Symptoms can reoccur, producing a telltale pattern of fever lasting roughly 3 days, followed by 7 days without fever, followed by another 3 days of fever. Without antibiotic treatment, this process can repeat several times.

Keep rodents, especially chipmunks and squirrels, out of homes and cabins.

- Avoid sleeping in rodent-infested buildings whenever possible. Although rodent nests may not be visible, other evidence of rodent activity (e.g., droppings) are a sign that a building may be infested.

- Prevent tick bites. Use insect repellent containing DEET (on skin or clothing) or permethrin (applied to clothing or equipment).

- If you are renting a cabin and notice a rodent infestation, contact the owner to alert them.

- If you own a cabin, consult a licensed pest control professional who can safely:

- Identify and remove any rodent nests from walls, attics, crawl spaces, and floors. (Other diseases can be transmitted by rodent droppings—leave this job to a professional!)

- Treat “cracks and crevices” in the walls with pesticide.

- Establish a pest control plan to keep rodents out.

Before You Go Outdoors

- Know where to expect ticks. Ticks live in grassy, brushy, or wooded areas, or even on animals. Spending time outside walking your dog, camping, gardening, or hunting could bring you in close contact with ticks. Many people get ticks in their own yard or neighborhood.

- Treat clothing and gear with products containing 0.5% permethrin. Permethrin can be used to treat boots, clothing and camping gear and remain protective through several washings. Alternatively, you can buy permethrin-treated clothing and gear.

- Use Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)-registered insect repellents containing DEET, picaridin, IR3535, Oil of Lemon Eucalyptus (OLE), para-menthane-diol (PMD), or 2-undecanone. Always follow product instructions. Do not use products containing OLE or PMD on children under 3 years old.

- Avoid Contact with Ticks

- Avoid wooded and brushy areas with high grass and leaf litter.

- Walk in the center of trails.

After You Come Indoors

Check your clothing for ticks. Ticks may be carried into the house on clothing. Any ticks that are found should be removed. Tumble dry clothes in a dryer on high heat for 10 minutes to kill ticks on dry clothing after you come indoors. If the clothes are damp, additional time may be needed. If the clothes require washing first, hot water is recommended. Cold and medium temperature water will not kill ticks.

Examine gear and pets. Ticks can ride into the home on clothing and pets, then attach to a person later, so carefully examine pets, coats, and daypacks.

Shower soon after being outdoors. Showering within two hours of coming indoors has been shown to reduce your risk of getting Lyme disease and may be effective in reducing the risk of other tickborne diseases. Showering may help wash off unattached ticks and it is a good opportunity to do a tick check.

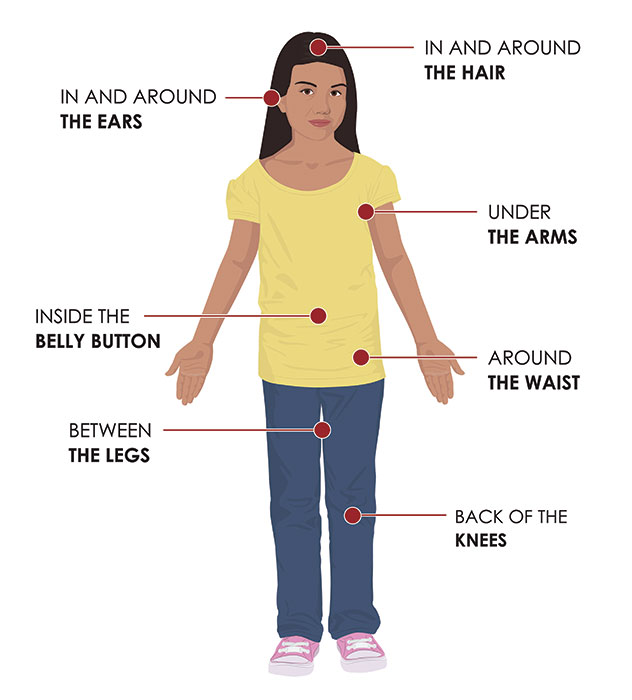

Check your body for ticks after being outdoors. Conduct a full body check upon return from potentially tick-infested areas, including your own backyard. Use a hand-held or full-length mirror to view all parts of your body. Check these parts of your body and your child’s body for ticks:

- Under the arms

- In and around the ears

- Inside belly button

- Back of the knees

- In and around the hair

- Between the legs

- Around the waist

. Sporozoites infect liver cells

. Sporozoites infect liver cells  and mature into schizonts

and mature into schizonts  , which rupture and release merozoites

, which rupture and release merozoites  . (Of note, in P. vivax and P. ovale a dormant stage [hypnozoites] can persist in the liver (if untreated) and cause relapses by invading the bloodstream weeks, or even years later.) After this initial replication in the liver (exo-erythrocytic schizogony

. (Of note, in P. vivax and P. ovale a dormant stage [hypnozoites] can persist in the liver (if untreated) and cause relapses by invading the bloodstream weeks, or even years later.) After this initial replication in the liver (exo-erythrocytic schizogony  ), the parasites undergo asexual multiplication in the erythrocytes (erythrocytic schizogony

), the parasites undergo asexual multiplication in the erythrocytes (erythrocytic schizogony  ). Merozoites infect red blood cells

). Merozoites infect red blood cells  . The ring stage trophozoites mature into schizonts, which rupture releasing merozoites

. The ring stage trophozoites mature into schizonts, which rupture releasing merozoites  . Blood stage parasites are responsible for the clinical manifestations of the disease. The gametocytes, male (microgametocytes) and female (macrogametocytes), are ingested by an Anopheles mosquito during a blood meal

. Blood stage parasites are responsible for the clinical manifestations of the disease. The gametocytes, male (microgametocytes) and female (macrogametocytes), are ingested by an Anopheles mosquito during a blood meal  . The parasites’ multiplication in the mosquito is known as the sporogonic cycle

. The parasites’ multiplication in the mosquito is known as the sporogonic cycle  . While in the mosquito’s stomach, the microgametes penetrate the macrogametes generating zygotes

. While in the mosquito’s stomach, the microgametes penetrate the macrogametes generating zygotes  . The zygotes in turn become motile and elongated (ookinetes)

. The zygotes in turn become motile and elongated (ookinetes)  which invade the midgut wall of the mosquito where they develop into oocysts

which invade the midgut wall of the mosquito where they develop into oocysts  . The oocysts grow, rupture, and release sporozoites

. The oocysts grow, rupture, and release sporozoites , which make their way to the mosquito’s salivary glands. Inoculation of the sporozoites

, which make their way to the mosquito’s salivary glands. Inoculation of the sporozoites