2 Chapter 2-Environmental Health Regulations

Bill Of Rights to the United States Constitution[1]

The Bill of Rights is the first 10 Amendments to the Constitution. It spells out Americans’ rights in relation to their government. It guarantees civil rights and liberties to the individual—like freedom of speech, press, and religion. It sets rules for due process of law and reserves all powers not delegated to the Federal Government to the people or the States. And it specifies that “the enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.”

The First Amendment

The First Amendment provides several rights protections: to express ideas through speech and the press, to assemble or gather with a group to protest or for other reasons, and to ask the government to fix problems. It also protects the right to religious beliefs and practices. It prevents the government from creating or favoring a religion.

The Second Amendment

The Second Amendment protects the right to keep and bear arms.

The Third Amendment

The Third Amendment prevents government from forcing homeowners to allow soldiers to use their homes. Before the Revolutionary War, laws gave British soldiers the right to take over private homes.

The Fourth Amendment

The Fourth Amendment bars the government from unreasonable search and seizure of an individual or their private property.

The Fifth Amendment

The Fifth Amendment provides several protections for people accused of crimes. It states that serious criminal charges must be started by a grand jury. A person cannot be tried twice for the same offense (double jeopardy) or have property taken away without just compensation. People have the right against self-incrimination and cannot be imprisoned without due process of law (fair procedures and trials.)

The Seventh Amendment

The Seventh Amendment extends the right to a jury trial in Federal civil cases.

The Eighth Amendment

The Eighth Amendment bars excessive bail and fines and cruel and unusual punishment.

The Ninth Amendment

The Ninth Amendment states that listing specific rights in the Constitution does not mean that people do not have other rights that have not been spelled out.

The Tenth Amendment

The Tenth Amendment says that the Federal Government only has those powers delegated in the Constitution. If it isn’t listed, it belongs to the states or to the people.

Graphic of original bill of Rights [2]

How A Bill Becomes a Law In Idaho[3]

A bill is a proposal for the enactment, amendment or repeal of an existing law, or for the appropriation of public money. A bill may originate in either the House or Senate, with the exception of revenue measures, which originate in the House of Representatives. It must be passed by a majority vote of each house of the Legislature and be signed into law by the Governor. If the Governor vetoes a bill, it can become law if the veto is overridden by a two-thirds majority of those present in each house. A bill can also become law without the Governor’s signature if it is not vetoed within five days (Sundays excepted) after presentation to the Governor. After the Legislature adjourns “sine die,” the Governor has ten days to veto or sign a bill.

Before the final vote on a bill, it must be read on three separate days in each house. Two-thirds of the members of the house where the bill is pending may vote to dispense with this provision.

Introduction

A bill may be introduced by a member, a group of members or a standing committee. After the 20th day of the session in the House and the 12th day in the Senate, bills may be introduced only by committee. After the 36th day bills may be introduced only by certain committees. In the House: State Affairs, Appropriations, Education, Revenue and Taxation, Health and Welfare and Ways and Means Committee. In the Senate: State Affairs, Finance, and Judiciary and Rules.

When the RS (proposed legislation) is approved after a short committee hearing, it is presented to the Chief Clerk or Secretary of the Senate and assigned a bill number. The bill is then introduced by being read on the floor in the 8th Order of Business in the House and the 11th Order of Business in the Senate. When a bill has been passed by one house it is transmitted to the other and follows the same process as any new bill. It will be introduced, referred to a committee for review and recommendation and then if sent to the floor will flow through the calendars (First Reading, Second Reading, and Third Reading) until reaching a final vote at the Third Reading Calendar.

First Reading

The bill is read the first time and is then referred by the Speaker of the House to the Judiciary, Rules and Administration Committee for printing. In the Senate the bill is referred by the presiding officer in the Senate to the Judiciary and Rules Committee for printing. After the bill is printed, it is reported back and referred to a standing committee by the Speaker in the House and the presiding officer in the Senate.

Reports of Standing Committees

Each committee to which a bill is referred conducts a study of all information that may help the committee determine the scope and effect of the proposed law. Studies may include research, hearings, expert testimony, and statements of interested parties. A bill may be reported out of committee with one of the following recommendations:

- Do Pass.

- Without recommendation.

- To be placed on General Orders for Amendment.

- Do not pass. (Bills are seldom released from committee with this recommendation.)

- Withdrawn with the privilege of introducing another bill (Senate only).

- Referred to the Clerk’s office for referral by the Speaker to another standing committee..

If a committee reports a bill out and does not recommend that the bill be amended or other action to keep it from going to the floor, the bill is then placed on the Second Reading Calendar.

Many bills are not reported out by committees and “die in committee.”

Second Reading

When a bill is reported out of committee, it is placed on the Second Reading Calendar and is read again. The following legislative day, the bill is automatically on the Third Reading Calendar unless other action has been taken.

Third Reading

The Clerk/Secretary of the Senate is required to read the entire bill, section by section, when it reaches “Third Reading of Bills” 11th Order of Business in the House and the 13th Order in the Senate. It is normal procedure, however, for the members to move to dispense with this reading at length.

It is at third reading that the bill is ready for debate and the final vote on passage of the bill is taken. Each bill is sponsored by a member who is known as the “floor sponsor.” This member opens and closes debate in favor of passage of the bill. After debate has closed, House members use an electronic voting system that tallies their votes; the Senate has a voice roll call vote tallied by the Secretary of the Senate. Each member present shall cast either an “aye” or “nay” vote. A bill is passed by a majority of those present. When a bill passes in one house it is then transmitted to the other house where it will follow a similar path. If a bill fails to pass, it is filed in the office of the Chief Clerk or Secretary of the Senate depending on the house of origin.

Once a bill has passed both houses it goes through the process of enrolling – during this process the Chief Clerk or Secretary of the Senate review each bill for accuracy. After the bill has been reviewed it is then submitted to both the Speaker of the House and President Pro Tempore/President of the Senate for signatures. The Chief Clerk (House bill) or Secretary of the Senate (Senate bill) also sign their bills. At each step of the process bills being sent between the two houses are accompanied by messages that are read across the desk so members, follow the progress of their bills. After all required signatures are obtained bills are transmitted to the Governor for final action (Governor signature, veto, law without signature).

Committee of the Whole

When a printed bill is to be amended, it is referred to the Committee of the Whole for amendment. At the proper Order of Business, the House or Senate resolves itself into a Committee of the Whole and the entire membership sits as one committee to consider changes to House and/or Senate bills that have been placed on a General Orders Calendar.

When a House/and or Senate bill has been amended by Committee of the Whole, it is engrossed by the body of origin. If a House bill is amended in the Senate the House must concur with the amendment before it can be engrossed. The same is true for a Senate bill amended in the House. Amendments are inserted into the bill (engrossed) and the engrossed bill is then placed on the calendar (First Reading of Engrossed Bills in the House and First Reading Calendar in the Senate) to be considered as a new bill. (see Joint Rule 2, House Rule 44 and Senate Rule 14).

Governor’s Action

After receiving a bill passed by both the House and Senate, the Governor may:

- Approve the bill by signing it within five days after its receipt (except Sundays), or within ten days after the Legislature adjourns at the end of the session

(“sine die”). - Allow the bill to become law without his approval by not signing it within the five days allowed.

- Disapprove (veto) the bill within five days and return it to the house of origin giving his reason for disapproval, or within ten days after the Legislature

adjourns “sine die.”

When a bill is approved by the Governor, becomes law without his approval, or through a veto override, it is transmitted to the Secretary of State for assignment of a chapter number in the Idaho Session Laws. Most bills become law on July 1, except in the case of a bill containing an emergency clause or other specific date of enactment. The final step is the addition of new laws to the Idaho Code, which contains all Idaho laws.

The following is a summary of the book by that name from Paul Charles Light. Although this book was written in 1995 it is still very true today if not worse then when he first identified the problem.[4]

Government is under enormous pressure to change. Call it reinventing, reengineering, or plain old change, but the mandate remains the same: produce more with less, and satisfy the customer while doing it. Yet, successful reform must involve more than exhortation and slogans. Paul Light argues that a failure to pay attention to the thickening of government over the past half century may doom any reinventing effort. The federal government has never had so many leaders.

There are more layers of management between the top and bottom of government, with more administrative units and occupants at each layer. Bill Clinton is further from the front lines of government than any president in American history. If the past decades are any indication, he will exit a presidency that is even thicker.

Light presents a revealing look at how thick the bureaucracy really is, how and why thickening occurs, what difference it might make, and what can be done to both reverse the process and keep the thickening from growing back. Light shows how the management layers between the top and bottom of government—between air traffic controllers and the Secretary of Transportation, food inspectors and the Secretary of Agriculture, and so on—have steadily increased.

In 1960, for example, John F. Kennedy’s senior-most appointments came in four layers: secretary, under secretary, assistant secretary, and deputy assistant secretary. By 1992, the number of layers had tripled. In the meantime, the number of occupants at each layer grew geometrically; the number of assistant secretaries jumped from 81 to 212. A government of managers means the president has very little direct access or control over what happens far below, a basic problem of accountability. Information gets distorted on the way up, and guidance gets lost on the way down.

Thickening often creates so many bureaucratic baffles that no one can be held accountable for any decision; mid-level workers may have so many bosses that they effectively have none. Light concludes that practically nothing by way of quality management, service-government, or employee involvement can work with these towering government agencies. But practically nothing will fail if a radical “down- layering” is undertaken now.

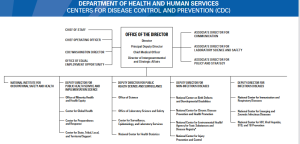

Example of multiple layers of government

Federal Health and Human Services[5]

-

Secretary

Deputy Secretary

Chief of Staff-

Immediate Office of the Secretary (IOS)

-

Office of Intergovernmental and External Affairs (IEA)

-

Office of the Secretary

-

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Administration (ASA)

-

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Financial Resources (ASFR)

-

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health (OASH)

-

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Legislation (ASL)

-

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE)

-

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR)*

-

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Public Affairs (ASPA)

-

Office for Civil Rights (OCR)

-

Departmental Appeals Board (DAB)

-

Office of the General Counsel (OGC)

-

Office of Global Affairs (OGA)*

-

Office of Inspector General (OIG)

-

Office of Medicare Hearings and Appeals (OMHA)

-

Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC)

-

HHS Chief Information Officer

-

-

Operating Divisions

-

Administration for Children and Families (ACF)

-

Administration for Community Living (ACL)

-

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)*

-

Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR)*

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)*

-

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS)

– PDF

-

Food and Drug Administration (FDA)*

-

Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA)*

-

Indian Health Service (IHS)*

-

National Institutes of Health (NIH)*

-

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)*

-

-

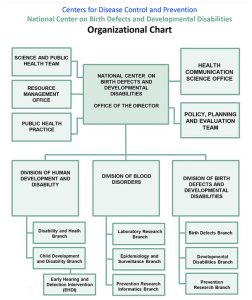

Looking at just CDC’s Org chart which one part of the entire HHS [6]

Then consider one element of the CDC which is the National Center on Birth Defects and Disabilities and you can see how far a decision has to move to be approved.[7]

- https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/bill-of-rights/what-does-it-say ↵

- https://cdn4.picryl.com/photo/1920/01/01/the-bill-of-rights-640.jpg ↵

- https://legislature.idaho.gov/resources/howabillbecomesalaw/ ↵

- https://www.amazon.com/Thickening-Government-Hierarchy-Diffusion-Accountability/dp/0815752490 ↵

- https://www.hhs.gov/about/agencies/orgchart/index.html ↵

- https://www.cdc.gov/about/organization/orgChart.htm ↵

- https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/AboutUs/images/Org-Chart.jpg ↵