7 Chapter 7 – Hazard Analysis Critical Control Points and Incident Command System (ICS)

GUIDELINES FOR APPLICATION OF HACCP PRINCIPLES

Introduction

HACCP is a management system in which food safety is addressed through the analysis and control of biological, chemical, and physical hazards from raw material production, procurement and handling, to manufacturing, distribution and consumption of the finished product. For successful implementation of a HACCP plan, management must be strongly committed to the HACCP concept. A firm commitment to HACCP by top management provides company employees with a sense of the importance of producing safe food.

HACCP is designed for use in all segments of the food industry from growing, harvesting, processing, manufacturing, distributing, and merchandising to preparing food for consumption. Prerequisite programs such as current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMPs) are an essential foundation for the development and implementation of successful HACCP plans. Food safety systems based on the HACCP principles have been successfully applied in food processing plants, retail food stores, and food service operations. The seven principles of HACCP have been universally accepted by government agencies, trade associations and the food industry around the world.

The following guidelines will facilitate the development and implementation of effective HACCP plans. While the specific application of HACCP to manufacturing facilities is emphasized here, these guidelines should be applied as appropriate to each segment of the food industry under consideration.

DEFINITIONS

CCP Decision Tree: A sequence of questions to assist in determining whether a control point is a CCP.

Control: (a) To manage the conditions of an operation to maintain compliance with established criteria. (b) The state where correct procedures are being followed and criteria are being met.

Control Measure: Any action or activity that can be used to prevent, eliminate or reduce a significant hazard.

Control Point: Any step at which biological, chemical, or physical factors can be controlled.

Corrective Action: Procedures followed when a deviation occurs.

Criterion: A requirement on which a judgement or decision can be based.

Critical Control Point: A step at which control can be applied and is essential to prevent or eliminate a food safety hazard or reduce it to an acceptable level.

Critical Limit: A maximum and/or minimum value to which a biological, chemical or physical parameter must be controlled at a CCP to prevent, eliminate or reduce to an acceptable level the occurrence of a food safety hazard.

Deviation: Failure to meet a critical limit.

HACCP: A systematic approach to the identification, evaluation, and control of food safety hazards.

HACCP Plan: The written document which is based upon the principles of HACCP and which delineates the procedures to be followed.

HACCP System: The result of the implementation of the HACCP Plan.

HACCP Team: The group of people who are responsible for developing, implementing and maintaining the HACCP system.

Hazard: A biological, chemical, or physical agent that is reasonably likely to cause illness or injury in the absence of its control.

Hazard Analysis: The process of collecting and evaluating information on hazards associated with the food under consideration to decide which are significant and must be addressed in the HACCP plan.

Monitor: To conduct a planned sequence of observations or measurements to assess whether a CCP is under control and to produce an accurate record for future use in verification.

Prerequisite Programs: Procedures, including Good Manufacturing Practices, that address operational conditions providing the foundation for the HACCP system.

Severity: The seriousness of the effect(s) of a hazard.

Step: A point, procedure, operation or stage in the food system from primary production to final consumption.

Validation: That element of verification focused on collecting and evaluating scientific and technical information to determine if the HACCP plan, when properly implemented, will effectively control the hazards.Verification: Those activities, other than monitoring, that determine the validity of the HACCP plan and that the system is operating according to the plan.

Prerequisite Programs

The production of safe food products requires that the HACCP system be built upon a solid foundation of prerequisite programs. Each segment of the food industry must provide the conditions necessary to protect food while it is under their control. This has traditionally been accomplished through the application of cGMPs. These conditions and practices are now considered to be prerequisite to the development and implementation of effective HACCP plans. Prerequisite programs provide the basic environmental and operating conditions that are necessary for the production of safe, wholesome food. Many of the conditions and practices are specified in federal, state and local regulations and guidelines (e.g., cGMPs and Food Code). The Codex Alimentarius General Principles of Food Hygiene describe the basic conditions and practices expected for foods intended for international trade. In addition to the requirements specified in regulations, industry often adopts policies and procedures that are specific to their operations. Many of these are proprietary. While prerequisite programs may impact upon the safety of a food, they also are concerned with ensuring that foods are wholesome and suitable for consumption . HACCP plans are narrower in scope, being limited to ensuring food is safe to consume.

The existence and effectiveness of prerequisite programs should be assessed during the design and implementation of each HACCP plan. All prerequisite programs should be documented and regularly audited. Prerequisite programs are established and managed separately from the HACCP plan. Certain aspects, however, of a prerequisite program may be incorporated into a HACCP plan. For example, many establishments have preventive maintenance procedures for processing equipment to avoid unexpected equipment failure and loss of production. During the development of a HACCP plan, the HACCP team may decide that the routine maintenance and calibration of an oven should be included in the plan as an activity of verification. This would further ensure that all the food in the oven is cooked to the minimum internal temperature that is necessary for food safety.

Developing a HACCP Plan

The format of HACCP plans will vary. In many cases the plans will be product and process specific. However, some plans may use a unit operations approach. Generic HACCP plans can serve as useful guides in the development of process and product HACCP plans; however, it is essential that the unique conditions within each facility be considered during the development of all components of the HACCP plan.

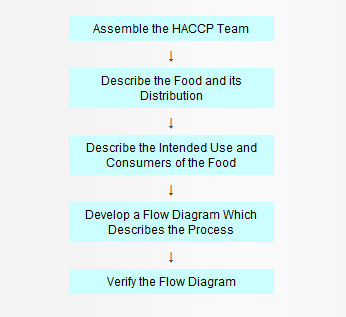

In the development of a HACCP plan, five preliminary tasks need to be accomplished before the application of the HACCP principles to a specific product and process. The five preliminary tasks are given in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Preliminary Tasks in the Development of the HACCP Plan

Assemble the HACCP Team

The first task in developing a HACCP plan is to assemble a HACCP team consisting of individuals who have specific knowledge and expertise appropriate to the product and process. It is the team’s responsibility to develop the HACCP plan. The team should be multi disciplinary and include individuals from areas such as engineering, production, sanitation, quality assurance, and food microbiology. The team should also include local personnel who are involved in the operation as they are more familiar with the variability and limitations of the operation. In addition, this fosters a sense of ownership among those who must implement the plan. The HACCP team may need assistance from outside experts who are knowledgeable in the potential biological, chemical and/or physical hazards associated with the product and the process. However, a plan which is developed totally by outside sources may be erroneous, incomplete, and lacking in support at the local level.

Due to the technical nature of the information required for hazard analysis, it is recommended that experts who are knowledgeable in the food process should either participate in or verify the completeness of the hazard analysis and the HACCP plan. Such individuals should have the knowledge and experience to correctly: (a) conduct a hazard analysis; (b) identify potential hazards; (c) identify hazards which must be controlled; (d) recommend controls, critical limits, and procedures for monitoring and verification; (e) recommend appropriate corrective actions when a deviation occurs; (f) recommend research related to the HACCP plan if important information is not known; and (g) validate the HACCP plan.

Describe the food and its distribution

The HACCP team first describes the food. This consists of a general description of the food, ingredients, and processing methods. The method of distribution should be described along with information on whether the food is to be distributed frozen, refrigerated, or at ambient temperature.

Describe the intended use and consumers of the food

Describe the normal expected use of the food. The intended consumers may be the general public or a particular segment of the population (e.g., infants, immunocompromised individuals, the elderly, etc.).

Develop a flow diagram which describes the process

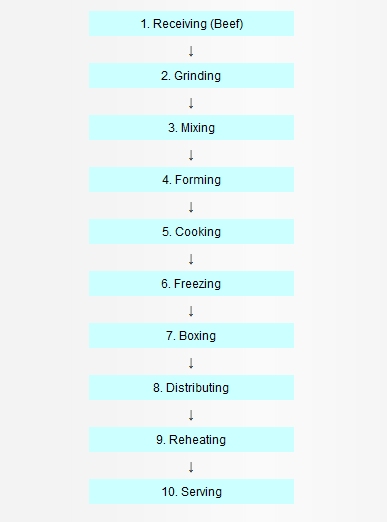

The purpose of a flow diagram is to provide a clear, simple outline of the steps involved in the process. The scope of the flow diagram must cover all the steps in the process which are directly under the control of the establishment. In addition, the flow diagram can include steps in the food chain which are before and after the processing that occurs in the establishment. The flow diagram need not be as complex as engineering drawings. A block type flow diagram is sufficiently descriptive (see Appendix B). Also, a simple schematic of the facility is often useful in understanding and evaluating product and process flow.

Appendix B Example of a Flow Diagram for the Production of Frozen Cooked Beef Patties

Verify the flow diagram

The HACCP team should perform an on-site review of the operation to verify the accuracy and completeness of the flow diagram. Modifications should be made to the flow diagram as necessary and documented.

After these five preliminary tasks have been completed, the seven principles of HACCP are applied.

Conduct a hazard analysis (Principle 1)

After addressing the preliminary tasks discussed above, the HACCP team conducts a hazard analysis and identifies appropriate control measures. The purpose of the hazard analysis is to develop a list of hazards which are of such significance that they are reasonably likely to cause injury or illness if not effectively controlled. Hazards that are not reasonably likely to occur would not require further consideration within a HACCP plan. It is important to consider in the hazard analysis the ingredients and raw materials, each step in the process, product storage and distribution, and final preparation and use by the consumer. When conducting a hazard analysis, safety concerns must be differentiated from quality concerns. A hazard is defined as a biological, chemical or physical agent that is reasonably likely to cause illness or injury in the absence of its control. Thus, the word hazard as used in this document is limited to safety.

A thorough hazard analysis is the key to preparing an effective HACCP plan. If the hazard analysis is not done correctly and the hazards warranting control within the HACCP system are not identified, the plan will not be effective regardless of how well it is followed.

The hazard analysis and identification of associated control measures accomplish three objectives: Those hazards and associated control measures are identified. The analysis may identify needed modifications to a process or product so that product safety is further assured or improved. The analysis provides a basis for determining CCPs in Principle 2.

The process of conducting a hazard analysis involves two stages. The first, hazard identification, can be regarded as a brain storming session. During this stage, the HACCP team reviews the ingredients used in the product, the activities conducted at each step in the process and the equipment used, the final product and its method of storage and distribution, and the intended use and consumers of the product. Based on this review, the team develops a list of potential biological, chemical or physical hazards which may be introduced, increased, or controlled at each step in the production process. A knowledge of any adverse health-related events historically associated with the product will be of value in this exercise.

After the list of potential hazards is assembled, stage two, the hazard evaluation, is conducted. In stage two of the hazard analysis, the HACCP team decides which potential hazards must be addressed in the HACCP plan. During this stage, each potential hazard is evaluated based on the severity of the potential hazard and its likely occurrence. Severity is the seriousness of the consequences of exposure to the hazard. Considerations of severity (e.g., impact of sequelae, and magnitude and duration of illness or injury) can be helpful in understanding the public health impact of the hazard. Consideration of the likely occurrence is usually based upon a combination of experience, epidemiological data, and information in the technical literature. When conducting the hazard evaluation, it is helpful to consider the likelihood of exposure and severity of the potential consequences if the hazard is not properly controlled. In addition, consideration should be given to the effects of short term as well as long term exposure to the potential hazard. Such considerations do not include common dietary choices which lie outside of HACCP. During the evaluation of each potential hazard, the food, its method of preparation, transportation, storage and persons likely to consume the product should be considered to determine how each of these factors may influence the likely occurrence and severity of the hazard being controlled. The team must consider the influence of likely procedures for food preparation and storage and whether the intended consumers are susceptible to a potential hazard. However, there may be differences of opinion, even among experts, as to the likely occurrence and severity of a hazard. The HACCP team may have to rely upon the opinion of experts who assist in the development of the HACCP plan.

Hazards identified in one operation or facility may not be significant in another operation producing the same or a similar product. For example, due to differences in equipment and/or an effective maintenance program, the probability of metal contamination may be significant in one facility but not in another. A summary of the HACCP team deliberations and the rationale developed during the hazard analysis should be kept for future reference. This information will be useful during future reviews and updates of the hazard analysis and the HACCP plan.

Appendix D gives three examples of using a logic sequence in conducting a hazard analysis. While these examples relate to biological hazards, chemical and physical hazards are equally important to consider. Appendix D is for illustration purposes to further explain the stages of hazard analysis for identifying hazards. Hazard identification and evaluation as outlined in Appendix D may eventually be assisted by biological risk assessments as they become available. While the process and output of a risk assessment (NACMCF, 1997)(1) is significantly different from a hazard analysis, the identification of hazards of concern and the hazard evaluation may be facilitated by information from risk assessments. Thus, as risk assessments addressing specific hazards or control factors become available, the HACCP team should take these into consideration.

APPENDIX D

| Hazard Analysis Stage | Frozen cooked beef patties produced in a manufacturing plant | Product containing eggs prepared for foodservice | Commercial frozen pre-cooked, boned chicken for further processing | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1Determine potential Hazard hazards associated

Identification with product |

Enteric pathogens (i.e., E. coli O157:H7 and Salmonella) | Salmonella in finished product. | Staphylococcus aureus in finished product. | |

| Stage 2 Hazard Evaluation | Assess severity of health consequences if potential hazard is not properly controlled. | Epidemiological evidence indicates that these pathogens cause severe health effects including death among children and elderly. Undercooked beef patties have been linked to disease from these pathogens. | Salmonellosis is a food borne infection causing a moderate to severe illness that can be caused by ingestion of only a few cells of Salmonella. | Certain strains of S. aureus produce an enterotoxin which can cause a moderate foodborne illness. |

| Determine likelihood of occurrence of potential hazard if not properly controlled. | E. coli O157:H7 is of very low probability and salmonellae is of moderate probability in raw meat. | Product is made with liquid eggs which have been associated with past outbreaks of salmonellosis. Recent problems with Salmonella serotype Enteritidis in eggs cause increased concern. Probability of Salmonella in raw eggs cannot be ruled out.

If not effectively controlled, some consumers are likely to be exposed to Salmonella from this food. |

Product may be contaminated with S. aureus due to human handling during boning of cooked chicken. Enterotoxin capable of causing illness will only occur as S. aureus multiplies to about 1,000,000/g. Operating procedures during boning and subsequent freezing prevent growth of S. aureus, thus the potential for enterotoxin formation is very low. | |

| Using information above, determine if this potential hazard is to be addressed in the HACCP plan. | The HACCP team decides that enteric pathogens are hazards for this product.

Hazards must be addressed in the plan. |

HACCP team determines that if the potential hazard is not properly controlled, consumption of product is likely to result in an unacceptable health risk.

Hazard must be addressed in the plan. |

The HACCP team determines that the potential for enterotoxin formation is very low. However, it is still desirable to keep the initial number of S. aureus organisms low. Employee practices that minimize contamination, rapid carbon dioxide freezing and handling instructions have been adequate to control this potential hazard.

Potential hazard does not need to be addressed in plan. |

|

* For illustrative purposes only. The potential hazards identified may not be the only hazards associated with the products listed. The responses may be different for different establishments.

Upon completion of the hazard analysis, the hazards associated with each step in the production of the food should be listed along with any measure(s) that are used to control the hazard(s). The term control measure is used because not all hazards can be prevented, but virtually all can be controlled. More than one control measure may be required for a specific hazard. On the other hand, more than one hazard may be addressed by a specific control measure (e.g. pasteurization of milk).

For example, if a HACCP team were to conduct a hazard analysis for the production of frozen cooked beef patties (Appendices B and D), enteric pathogens (e.g., Salmonella and verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli) in the raw meat would be identified as hazards. Cooking is a control measure which can be used to eliminate these hazards. The following is an excerpt from a hazard analysis summary table for this product.

| Step | Potential Hazard(s) | Justification | Hazard to be addressed in plan? Y/N |

Control Measure(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5. Cooking | Enteric pathogens: e.g., Salmonella, verotoxigenic-E. coli |

enteric pathogens have been associated with outbreaks of foodborne illness from undercooked ground beef | Y | Cooking |

The hazard analysis summary could be presented in several different ways. One format is a table such as the one given above. Another could be a narrative summary of the HACCP team’s hazard analysis considerations and a summary table listing only the hazards and associated control measures.

Determine critical control points (CCPs) (Principle 2)

A critical control point is defined as a step at which control can be applied and is essential to prevent or eliminate a food safety hazard or reduce it to an acceptable level. The potential hazards that are reasonably likely to cause illness or injury in the absence of their control must be addressed in determining CCPs.

Complete and accurate identification of CCPs is fundamental to controlling food safety hazards. The information developed during the hazard analysis is essential for the HACCP team in identifying which steps in the process are CCPs. One strategy to facilitate the identification of each CCP is the use of a CCP decision tree. Although application of the CCP decision tree can be useful in determining if a particular step is a CCP for a previously identified hazard, it is merely a tool and not a mandatory element of HACCP. A CCP decision tree is not a substitute for expert knowledge.

Important considerations when using the decision tree:

- The decision tree is used after the hazard analysis.

- The decision tree then is used at the steps where a hazard that must be addressed in the HACCP plan has been identified.

- A subsequent step in the process may be more effective for controlling a hazard and may be the preferred CCP.

- More than one step in a process may be involved in controlling a hazard.

- More than one hazard may be controlled by a specific control measure.

* Proceed to next step in the process.

Critical control points are located at any step where hazards can be either prevented, eliminated, or reduced to acceptable levels. Examples of CCPs may include: thermal processing, chilling, testing ingredients for chemical residues, product formulation control, and testing product for metal contaminants. CCPs must be carefully developed and documented. In addition, they must be used only for purposes of product safety. For example, a specified heat process, at a given time and temperature designed to destroy a specific microbiological pathogen, could be a CCP. Likewise, refrigeration of a precooked food to prevent hazardous microorganisms from multiplying, or the adjustment of a food to a pH necessary to prevent toxin formation could also be CCPs. Different facilities preparing similar food items can differ in the hazards identified and the steps which are CCPs. This can be due to differences in each facility’s layout, equipment, selection of ingredients, processes employed, etc.

Establish critical limits (Principle 3)

A critical limit is a maximum and/or minimum value to which a biological, chemical or physical parameter must be controlled at a CCP to prevent, eliminate or reduce to an acceptable level the occurrence of a food safety hazard. A critical limit is used to distinguish between safe and unsafe operating conditions at a CCP. Critical limits should not be confused with operational limits which are established for reasons other than food safety.

Each CCP will have one or more control measures to assure that the identified hazards are prevented, eliminated or reduced to acceptable levels. Each control measure has one or more associated critical limits. Critical limits may be based upon factors such as: temperature, time, physical dimensions, humidity, moisture level, water activity (aw), pH, titratable acidity, salt concentration, available chlorine, viscosity, preservatives, or sensory information such as aroma and visual appearance. Critical limits must be scientifically based. For each CCP, there is at least one criterion for food safety that is to be met. An example of a criterion is a specific lethality of a cooking process such as a 5D reduction in Salmonella. The critical limits and criteria for food safety may be derived from sources such as regulatory standards and guidelines, literature surveys, experimental results, and experts.

An example is the cooking of beef patties (Appendix B). The process should be designed to ensure the production of a safe product. The hazard analysis for cooked meat patties identified enteric pathogens (e.g., verotoxigenic E. coli such as E. coli O157:H7, and salmonellae) as significant biological hazards. Furthermore, cooking is the step in the process at which control can be applied to reduce the enteric pathogens to an acceptable level. To ensure that an acceptable level is consistently achieved, accurate information is needed on the probable number of the pathogens in the raw patties, their heat resistance, the factors that influence the heating of the patties, and the area of the patty which heats the slowest. Collectively, this information forms the scientific basis for the critical limits that are established. Some of the factors that may affect the thermal destruction of enteric pathogens are listed in the following table. In this example, the HACCP team concluded that a thermal process equivalent to 155° F for 16 seconds would be necessary to assure the safety of this product. To ensure that this time and temperature are attained, the HACCP team for one facility determined that it would be necessary to establish critical limits for the oven temperature and humidity, belt speed (time in oven), patty thickness and composition (e.g., all beef, beef and other ingredients). Control of these factors enables the facility to produce a wide variety of cooked patties, all of which will be processed to a minimum internal temperature of 155° F for 16 seconds. In another facility, the HACCP team may conclude that the best approach is to use the internal patty temperature of 155° F and hold for 16 seconds as critical limits. In this second facility the internal temperature and hold time of the patties are monitored at a frequency to ensure that the critical limits are constantly met as they exit the oven. The example given below applies to the first facility.

| Process Step | CCP | Critical Limits |

|---|---|---|

| 5. Cooking | YES | Oven temperature:___° F Time; rate of heating and cooling (belt speed in ft/min): ____ft/min Patty thickness: ____in. Patty composition: e.g. all beef Oven humidity: ____% RH |

Establish monitoring procedures (Principle 4)

Monitoring is a planned sequence of observations or measurements to assess whether a CCP is under control and to produce an accurate record for future use in verification. Monitoring serves three main purposes. First, monitoring is essential to food safety management in that it facilitates tracking of the operation. If monitoring indicates that there is a trend towards loss of control, then action can be taken to bring the process back into control before a deviation from a critical limit occurs. Second, monitoring is used to determine when there is loss of control and a deviation occurs at a CCP, i.e., exceeding or not meeting a critical limit. When a deviation occurs, an appropriate corrective action must be taken. Third, it provides written documentation for use in verification.

An unsafe food may result if a process is not properly controlled and a deviation occurs. Because of the potentially serious consequences of a critical limit deviation, monitoring procedures must be effective. Ideally, monitoring should be continuous, which is possible with many types of physical and chemical methods. For example, the temperature and time for the scheduled thermal process of low-acid canned foods is recorded continuously on temperature recording charts. If the temperature falls below the scheduled temperature or the time is insufficient, as recorded on the chart, the product from the retort is retained and the disposition determined as in Principle 5. Likewise, pH measurement may be performed continually in fluids or by testing each batch before processing. There are many ways to monitor critical limits on a continuous or batch basis and record the data on charts. Continuous monitoring is always preferred when feasible. Monitoring equipment must be carefully calibrated for accuracy.

Assignment of the responsibility for monitoring is an important consideration for each CCP. Specific assignments will depend on the number of CCPs and control measures and the complexity of monitoring. Personnel who monitor CCPs are often associated with production (e.g., line supervisors, selected line workers and maintenance personnel) and, as required, quality control personnel. Those individuals must be trained in the monitoring technique for which they are responsible, fully understand the purpose and importance of monitoring, be unbiased in monitoring and reporting, and accurately report the results of monitoring. In addition, employees should be trained in procedures to follow when there is a trend towards loss of control so that adjustments can be made in a timely manner to assure that the process remains under control. The person responsible for monitoring must also immediately report a process or product that does not meet critical limits.

All records and documents associated with CCP monitoring should be dated and signed or initialed by the person doing the monitoring.

When it is not possible to monitor a CCP on a continuous basis, it is necessary to establish a monitoring frequency and procedure that will be reliable enough to indicate that the CCP is under control. Statistically designed data collection or sampling systems lend themselves to this purpose.

Most monitoring procedures need to be rapid because they relate to on-line, “real-time” processes and there will not be time for lengthy analytical testing. Examples of monitoring activities include: visual observations and measurement of temperature, time, pH, and moisture level.

Microbiological tests are seldom effective for monitoring due to their time-consuming nature and problems with assuring detection of contaminants. Physical and chemical measurements are often preferred because they are rapid and usually more effective for assuring control of microbiological hazards. For example, the safety of pasteurized milk is based upon measurements of time and temperature of heating rather than testing the heated milk to assure the absence of surviving pathogens.

With certain foods, processes, ingredients, or imports, there may be no alternative to microbiological testing. However, it is important to recognize that a sampling protocol that is adequate to reliably detect low levels of pathogens is seldom possible because of the large number of samples needed. This sampling limitation could result in a false sense of security by those who use an inadequate sampling protocol. In addition, there are technical limitations in many laboratory procedures for detecting and quantitating pathogens and/or their toxins.

Establish corrective actions (Principle 5)

The HACCP system for food safety management is designed to identify health hazards and to establish strategies to prevent, eliminate, or reduce their occurrence. However, ideal circumstances do not always prevail and deviations from established processes may occur. An important purpose of corrective actions is to prevent foods which may be hazardous from reaching consumers. Where there is a deviation from established critical limits, corrective actions are necessary. Therefore, corrective actions should include the following elements: (a) determine and correct the cause of non-compliance; (b) determine the disposition of non-compliant product and (c) record the corrective actions that have been taken. Specific corrective actions should be developed in advance for each CCP and included in the HACCP plan. As a minimum, the HACCP plan should specify what is done when a deviation occurs, who is responsible for implementing the corrective actions, and that a record will be developed and maintained of the actions taken. Individuals who have a thorough understanding of the process, product and HACCP plan should be assigned the responsibility for oversight of corrective actions. As appropriate, experts may be consulted to review the information available and to assist in determining disposition of non-compliant product.

Establish verification procedures (Principle 6)

Verification is defined as those activities, other than monitoring, that determine the validity of the HACCP plan and that the system is operating according to the plan. The NAS (1985) (2) pointed out that the major infusion of science in a HACCP system centers on proper identification of the hazards, critical control points, critical limits, and instituting proper verification procedures. These processes should take place during the development and implementation of the HACCP plans and maintenance of the HACCP system. An example of a verification schedule is given in Figure 2.

One aspect of verification is evaluating whether the facility’s HACCP system is functioning according to the HACCP plan. An effective HACCP system requires little end-product testing, since sufficient validated safeguards are built in early in the process. Therefore, rather than relying on end-product testing, firms should rely on frequent reviews of their HACCP plan, verification that the HACCP plan is being correctly followed, and review of CCP monitoring and corrective action records.

Another important aspect of verification is the initial validation of the HACCP plan to determine that the plan is scientifically and technically sound, that all hazards have been identified and that if the HACCP plan is properly implemented these hazards will be effectively controlled. Information needed to validate the HACCP plan often include (1) expert advice and scientific studies and (2) in-plant observations, measurements, and evaluations. For example, validation of the cooking process for beef patties should include the scientific justification of the heating times and temperatures needed to obtain an appropriate destruction of pathogenic microorganisms (i.e., enteric pathogens) and studies to confirm that the conditions of cooking will deliver the required time and temperature to each beef patty.

Subsequent validations are performed and documented by a HACCP team or an independent expert as needed. For example, validations are conducted when there is an unexplained system failure; a significant product, process or packaging change occurs; or new hazards are recognized.

In addition, a periodic comprehensive verification of the HACCP system should be conducted by an unbiased, independent authority. Such authorities can be internal or external to the food operation. This should include a technical evaluation of the hazard analysis and each element of the HACCP plan as well as on-site review of all flow diagrams and appropriate records from operation of the plan. A comprehensive verification is independent of other verification procedures and must be performed to ensure that the HACCP plan is resulting in the control of the hazards. If the results of the comprehensive verification identifies deficiencies, the HACCP team modifies the HACCP plan as necessary.

Verification activities are carried out by individuals within a company, third party experts, and regulatory agencies. It is important that individuals doing verification have appropriate technical expertise to perform this function. The role of regulatory and industry in HACCP was further described by the NACMCF (1994) (3).

Figure 2. Example of a Company Established HACCP Verification Schedule

| Activity | Frequency | Responsibility | Reviewer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Verification Activities Scheduling | Yearly or Upon HACCP System Change | HACCP Coordinator | Plant Manager |

| Initial Validation of HACCP Plan | Prior to and During Initial Implementation of Plan | Independent Expert(s)(a) | HACCP Team |

| Subsequent validation of HACCP Plan | When Critical Limits Changed, Significant Changes in Process, Equipment Changed, After System Failure, etc. | Independent Expert(s)(a) | HACCP Team |

| Verification of CCP Monitoring as Described in the Plan (e.g., monitoring of patty cooking temperature) | According to HACCP Plan (e.g., once per shift) | According to HACCP Plan (e.g., Line Supervisor) | According to HACCP Plan (e.g., Quality Control) |

| Review of Monitoring, Corrective Action Records to Show Compliance with the Plan | Monthly | Quality Assurance | HACCP Team |

| Comprehensive HACCP System Verification | Yearly | Independent Expert(s)(a) | Plant Manager |

| (a) Done by others than the team writing and implementing the plan. May require additional technical expertise as well as laboratory and plant test studies. | |||

Establish record-keeping and documentation procedures (Principle 7)

Generally, the records maintained for the HACCP System should include the following:

- A summary of the hazard analysis, including the rationale for determining hazards and control measures.

- The HACCP PlanListing of the HACCP team and assigned responsibilities.Description of the food, its distribution, intended use, and consumer.Verified flow diagram.HACCP Plan Summary Table that includes information for:

Steps in the process that are CCPs

The hazard(s) of concern.

Critical limits

Monitoring*

Corrective actions*

Verification procedures and schedule*

Record-keeping procedures*

* A brief summary of position responsible for performing the activity and the procedures and frequency should be provided

The following is an example of a HACCP plan summary table:

CCP Hazards Critical limit(s) Monitoring Corrective Actions Verification Records - Support documentation such as validation records.

- Records that are generated during the operation of the plan.[1]

Incident Command and Emergency Operations Centers

CDC Emergency Operations Center: How an EOC Works.

A Model for Response

The CDC EOC uses the National Incident Management System to better manage and coordinate emergency responses.

An Incident Management System (IMS) is an internationally recognized model for responding to emergencies. Having an IMS in place reduces harm and saves lives.

IMS is a temporary, formal organization structure that is activated to support a response, adjusted to meet rapidly changing demands of that response, and is then disbanded at the end of the response.

An IMS outlines the specific roles and responsibilities of responders during an event, providing a common framework for government, the private sector, and nongovernmental organizations to work seamlessly together. In IMS, each person is assigned a specific role and follows a set command structure. The level of complexity of an incident dictates which roles are activated. In certain scenarios, incident management staff may cover more than one role at a time

Incident management helps with:

- Directing specific incident operations

- Acquiring, coordinating, and delivering resources to incident sites

- Sharing information about the incident with the public

An IMS is a flexible, integrated system that can be used for any incident regardless of cause, size, location, or complexity.

Exercises

In addition to responding to real world incidents, the EOC also conducts exercises to evaluate its ability to respond rapidly and effectively to potential public health emergencies. Examples of exercises include simulated incidents such as hurricanes, the detonation of radiological dispersal devices (i.e., dirty bombs), and an outbreak of pandemic influenza.

Here are a few of the most recent times the EOC was activated:

- 2014: MERS-CoV

- Unaccompanied Children

- Ebola Outbreak 2013 H7N9

- Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV)

- 2012: Polio

- Meningitis Outbreak

- Hurricane Sandy

- 2011: Japan Earthquake and Tsunami

- Polio Eradication Response

- Hurricane Irene

- 2010: New Hampshire Anthrax

- Haiti Earthquake

- Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill

- Haiti Cholera Outbreak

- 2009: Salmonella typhimurium outbreak

- Presidential Inauguration

- H1N1 Influenza[2]

EMERGENCY SUPPORT FUNCTION ANNEXES:

INTRODUCTION

Purpose

This section provides an overview of the Emergency Support Function (ESF) structure, common elements of each of the ESFs, and the basic content contained in each of the ESF Annexes. The following section includes a series of annexes describing the roles and responsibilities of Federal departments and agencies as ESF coordinators, primary agencies, or support agencies.

Background

The ESFs provide the structure for coordinating Federal interagency support for a Federal response to an incident. They are mechanisms for grouping functions most frequently used to provide Federal support to States and Federal-to-Federal support, both for declared disasters and emergencies under the Stafford Act and for non-Stafford Act incidents (see Table 1).

The Incident Command System provides for the flexibility to assign ESF and other stakeholder resources according to their capabilities, taskings, and requirements to augment and support the other sections of the Joint Field Office (JFO)/Regional Response Coordination Center (RRCC) or National Response Coordination Center (NRCC) in order to respond to incidents in a more collaborative and cross-cutting manner.

While ESFs are typically assigned to a specific section at the NRCC or in the JFO/RRCC for management purposes, resources may be assigned anywhere within the Unified Coordination structure. Regardless of the section in which an ESF may reside, that entity works in conjunction with other JFO sections to ensure that appropriate planning and execution of missions occur.

Table 1. Roles and Responsibilities of the ESFs ESF

| Scope | |

| ESF #1 – Transportation | Aviation/airspace management and control Transportation safety

Restoration/recovery of transportation infrastructure Movement restrictions Damage and impact assessment |

| ESF #2 –

Communications |

Coordination with telecommunications and information technology industries

Restoration and repair of telecommunications infrastructure Protection, restoration, and sustainment of national cyber and information technology resources Oversight of communications within the Federal incident management and response structures |

| ESF #3 – Public Works and Engineering | Infrastructure protection and emergency repair Infrastructure restoration

Engineering services and construction management Emergency contracting support for life-saving and life-sustaining services |

| ESF #4 – Firefighting | Coordination of Federal firefighting activities

Support to wildland, rural, and urban firefighting operations |

| ESF | Scope |

| ESF #5 – Emergency Management | Coordination of incident management and response efforts Issuance of mission assignments

Resource and human capital Incident action planning Financial management |

| ESF #6 – Mass Care, Emergency Assistance, Housing, and Human Services | Mass care

Emergency assistance Disaster housing Human services |

| ESF #7 – Logistics Management and Resource Support | Comprehensive, national incident logistics planning, management, and sustainment capability

Resource support (facility space, office equipment and supplies, contracting services, etc.) |

| ESF #8 – Public Health and Medical Services | Public health Medical

Mental health services Mass fatality management |

| ESF #9 – Search and Rescue | Life-saving assistance

Search and rescue operations |

| ESF #10 – Oil and Hazardous Materials Response | Oil and hazardous materials (chemical, biological, radiological, etc.) response

Environmental short- and long-term cleanup |

| ESF #11 – Agriculture and Natural Resources | Nutrition assistance

Animal and plant disease and pest response Food safety and security Natural and cultural resources and historic properties protection and restoration Safety and well-being of household pets |

| ESF #12 – Energy | Energy infrastructure assessment, repair, and restoration Energy industry utilities coordination

Energy forecast |

| ESF #13 – Public Safety and Security | Facility and resource security

Security planning and technical resource assistance Public safety and security support Support to access, traffic, and crowd control |

| ESF #14 – Long-Term Community Recovery | Social and economic community impact assessment

Long-term community recovery assistance to States, local governments, and the private sector Analysis and review of mitigation program implementation |

| ESF #15 – External Affairs | Emergency public information and protective action guidance Media and community relations

Congressional and international affairs Tribal and insular affairs |

ESF Notification and Activation

The NRCC, a component of the National Operations Center (NOC), develops and issues operations orders to activate individual ESFs based on the scope and magnitude of the threat or incident.

ESF primary agencies are notified of the operations orders and time to report to the NRCC by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS)/Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Operations Center. At the regional level, ESFs are notified by the RRCC per established protocols.

ESF primary agencies notify and activate support agencies as required for the threat or incident, to include support to specialized teams. Each ESF is required to develop standard operating procedures (SOPs) and notification protocols and to maintain current rosters and contact information.

ESF Member Roles and Responsibilities Each ESF Annex identifies the coordinator and the primary and support agencies pertinent to the ESF. Several ESFs incorporate multiple components, with primary agencies designated for each component to ensure seamless integration of and transition between preparedness, response, and recovery activities. ESFs with multiple primary agencies designate an ESF coordinator for the purposes of preincident planning and coordination of primary and supporting agency efforts throughout the incident. Following is a discussion of the roles and responsibilities of the ESF coordinator and the primary and support agencies.

ESF Coordinator The ESF coordinator is the entity with management oversight for that particular ESF. The coordinator has ongoing responsibilities throughout the preparedness, response, and recovery phases of incident management. The role of the ESF coordinator is carried out through a “unified command” approach as agreed upon collectively by the designated primary agencies and, as appropriate, support agencies. Responsibilities of the ESF coordinator include:

- Coordination before, during, and after an incident, including preincident planning and coordination.

- Maintaining ongoing contact with ESF primary and support agencies.

- Conducting periodic ESF meetings and conference calls.

- Coordinating efforts with corresponding private-sector organizations.

- Coordinating ESF activities relating to catastrophic incident planning and critical infrastructure preparedness, as appropriate.

Primary Agencies An ESF primary agency is a Federal agency with significant authorities, roles, resources, or capabilities for a particular function within an ESF. ESFs may have multiple primary agencies, and the specific responsibilities of those agencies are articulated within the relevant ESF Annex. A Federal agency designated as an ESF primary agency serves as a Federal executive agent under the Federal Coordinating Officer (or Federal Resource Coordinator for non-Stafford Act incidents) to accomplish the ESF mission. When an ESF is activated in response to an incident, the primary agency is responsible for:

- Supporting the ESF coordinator and coordinating closely with the other primary and support agencies.

- Orchestrating Federal support within their functional area for an affected State.

- Providing staff for the operations functions at fixed and field facilities.

- Notifying and requesting assistance from support agencies.

- Managing mission assignments and coordinating with support agencies, as well as appropriate State officials, operations centers, and agencies.

- Working with appropriate private-sector organizations to maximize use of all available resources.

- Supporting and keeping other ESFs and organizational elements informed of ESF operational priorities and activities.

- Conducting situational and periodic readiness assessments.

- Executing contracts and procuring goods and services as needed.

- Ensuring financial and property accountability for ESF activities.

- Planning for short- and long-term incident management and recovery operations.

- Maintaining trained personnel to support interagency emergency response and support teams.

- Identifying new equipment or capabilities required to prevent or respond to new or emerging threats and hazards, or to improve the ability to address existing threats.

Support Agencies Support agencies are those entities with specific capabilities or resources that support the primary agency in executing the mission of the ESF. When an ESF is activated, support agencies are responsible for:

Conducting operations, when requested by DHS or the designated ESF primary agency, consistent with their own authority and resources, except as directed otherwise pursuant to sections 402, 403, and 502 of the Stafford Act.

Participating in planning for short- and long-term incident management and recovery operations and the development of supporting operational plans, SOPs, checklists, or other job aids, in concert with existing first-responder standards.

- Assisting in the conduct of situational assessments.

- Furnishing available personnel, equipment, or other resource support as requested by DHS or the ESF primary agency.

- Providing input to periodic readiness assessments.

- Maintaining trained personnel to support interagency emergency response and support teams.

- Identifying new equipment or capabilities required to prevent or respond to new or emerging threats and hazards, or to improve the ability to address existing threats.

- When requested, and upon approval of the Secretary of Defense, the Department of Defense (DOD) provides Defense Support of Civil Authorities (DSCA) during domestic incidents.

- Accordingly, DOD is considered a support agency to all ESFs.[3]