1 Chapter 1 History of Public Health Preparedness, Legal Elements Related to Emergencies

This course is intended to provide a broad overview of how the public health system responds in times of emergency. To begin with lets look at what public health is in the following video from the American Public Health Association.

When one thinks about a public health response we are reminded of the Flu Worldwide Pandemic. Below you will find an description of the outbreak and the response.

01.08 Assignment Activity Direction- Comparison of actions during Covid Pandemic and 1917-1918 Pandemic – Link to Canvas Site

In this assignment you will be looking at the response as outlined in the reading with what you remember about the response to the recent Covid pandemic.

Download the worksheet and answers the prompts. Download 01.08 Assignment -Comparison of actions during Covid Pandemic and 1917-1918 Pandemic.docx

After you have completed the worksheet submit it in the area that is below this item.

Eliminating Small Pox

The work of Jenner

In 1797, Jenner sent a short communication to the Royal Society describing his experiment and observations. However, the paper was rejected. Then in 1798, having added a few more cases to his initial experiment, Jenner privately published a small booklet entitled An Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae Vaccinae, a disease discovered in some of the western counties of England, particularly Gloucestershire and Known by the Name of Cow Pox (18, 10). The Latin word for cow is vacca, and cowpox is vaccinia; Jenner decided to call this new procedure vaccination. The 1798 publication had three parts. In the first part Jenner presented his view regarding the origin of cowpox as a disease of horses transmitted to cows. The theory was discredited during Jenner’s lifetime. He then presented the hypothesis that infection with cowpox protects against subsequent infection with smallpox. The second part contained the critical observations relevant to testing the hypothesis. The third part was a lengthy discussion, in part polemical, of the findings and a variety of issues related to smallpox. The publication of the Inquiry was met with a mixed reaction in the medical community.liminating Small Pox IT all started with Jenner[1]

Influenza Pandemic 1917-1918

The responses of the Public Health Departments in Europe and in the United States represented the ideas prevalent in society and in the scientific community. While most of the measures were solidly grounded in the current scientific concepts, they could also be traced back to Medieval and even Classical times of plague and pestilence. The idea of contagion prompting quarantines and isolation dates back to the Justinian Plague. However, epidemiological work by Snow and others in the 19th century did further these notions of contagion and understanding of transmission. Public Health Departments grew out of these advances and the belief in the ability of man to control nature. Sanitation, vaccination

The responses of the Public Health Departments in Europe and in the United States represented the ideas prevalent in society and in the scientific community. While most of the measures were solidly grounded in the current scientific concepts, they could also be traced back to Medieval and even Classical times of plague and pestilence. The idea of contagion prompting quarantines and isolation dates back to the Justinian Plague. However, epidemiological work by Snow and others in the 19th century did further these notions of contagion and understanding of transmission. Public Health Departments grew out of these advances and the belief in the ability of man to control nature. Sanitation, vaccination

programs and other public hygiene efforts in the late 19th century enabled public health officials to gain power and authority. However, the Influenza Pandemic of 1918-19 challenged the public health agencies. The massive morbidities from the common illness of influenza were mysterious and frightening. Many of the measures formerly known to work were ineffective. They were not prepared for an event of this magnitude, lacking the organization and infrastructure and constrained by the war. Yet, the great war provided the rhetoric of nationalism necessary to usher in these authoritative responses and losses of liberty.

Authoritative MeasuresThe public health authorities in both the United States and Europe took up fundamental measures to control epidemics that dated back to Medieval times of the Bubonic Plague. They aimed to reduce the transmission of the pathogen by preventing contact. They framed their public health orders in scientific ideas of their understanding of how the influenza microbe spread through the air by coughing and sneezing, and their conception of the pathogenesis of influenza. Since they concluded that the pathogen was transmitted through the air, efforts to control contagion were organized to prevent those infected from sharing the same air as the uninfected. Public gatherings and the coming together of people in close quarters was seen as a potential agency for the transmission of the disease. The public health authorities believed that good ventilation and fresh air were “the best of all general measures for prevention, and this implies the avoidance of crowded meetings,” (BMJ, 10/19/1918). This translated into the controversial and imperative measure of closing of many public institutions and banning of public gatherings during the time of an epidemic.

The rigidity of these regulations varied immensely with the power of the local health departments and severity of the influenza outbreak. In the United States, the Committee of the American Public Health Association ( APHA) issued measures in a report to limit large gatherings. The committee held that any type of gathering of people, with the mixing of bodies and sharing of breath in crowded rooms, was dangerous. Nonessential meetings were to be prohibited. They determined that saloons, dance halls, and cinemas should be closed and public funerals should be prohibited since they were unnecessary assemblies.

Churches were allowed to remain open, but the committee believed that only the minimum services should be conducted and the intimacy reduced. Street cars were thought to be a special menace to society with poor ventilation, crowding and uncleanliness. The committee encouraged the staggering of opening and closing hours in stores and factories to prevent overcrowding and for people to walk to work when possible (JAMA, 12/21/1918). Some of the regulations in Britain were milder, such as limiting music hall performances to less than three consecutive hours and allowing a half-hour for ventilation between shows (BMJ, 11/30/1918). In Switzerland, theaters, cinemas, concerts and shooting matches were all suspended when the epidemic struck, which led to a state of panic (BMJ, 10/19/1918). This variation in response was most likely due to differences in authority of the public health agencies and societal acceptance of their measures as necessary. This necessitated a shared belief in the concept of contagion and some faith in the actions of science to allow them to overcome this plague.

The most frequently discussed and debated public health measure in the journals of the period was the closure of the schools. In Britain the prevalence of the epidemic led to the closure of the public elementary schools (BMJ, 11/30/1918). In France, students with any symptoms and their siblings were to be excluded from school. If three fourths of the students were absent then the whole class was to be dismissed for 15 days (JAMA, 12/7/1918). Some believed closing schools to be a useful measure to control infection but complained that it often occurred too late, after most students and teachers were sick (BMJ, 10/19/1918). In the United States, school closure was not as widely accepted. One article in JAMA said that, “the desirability of closing schools in a large city in the presence of an epidemic is a measure of doubtful value,” (10/5/1918). The APHA Committee debated its value too, questioning the effectiveness against the loss of educational standards. Generally, school closure was thought to be less effective in large urban metropolises than in rural centers where the school represented the point of dissemination of the infectious agent. The closing of schools and other public institutions as public health regulations to reduce the epidemic was not universally accepted. One editorial in the BMJ states that “every town-dweller who is susceptible must sooner or later contract influenza whatever the public health authorities may do; and that the more schools and public meetings are banned and the general life of the community dislocated the greater will be the unemployment and depression,” (12/21/1918).

The more restrictive methods of infection control issued by public health departments were quarantines and the isolation of the ill. These measures required a sacrifice of individual liberty for the societal good and therefore required a strong public health authority. Both the Illinois and New York State Health Departments ordered that patients must be quarantined until all clinical manifestations of the illness subsided. They held that the danger of the influenza epidemic was so grave that it was imperative to secure isolation for the patient (JAMA, 10/12/1918). The members of the APHA committee agreed in their report, saying that patients with influenza should to be kept in isolation. Because of the strain on facilities, only severe cases were to be hospitalized while mild influenza patients were to remain at home. The APHA also supported institutional quarantines to protect people from the outside world in establishments like asylums and colleges (JAMA, 12/21/1918). The use of institutional quarantines was applied to the many military training camps set up in the United States to prepare soldiers for war. These camps, with masses of men from throughout the country, were prime targets of huge influenza epidemics. The men were kept in strict isolation once ill and entire camps was often quarantined (JAMA, 4/12/1919). These measures were easily implemented in these camps where men were already committed to their country and the authority of the government.

The more restrictive methods of infection control issued by public health departments were quarantines and the isolation of the ill. These measures required a sacrifice of individual liberty for the societal good and therefore required a strong public health authority. Both the Illinois and New York State Health Departments ordered that patients must be quarantined until all clinical manifestations of the illness subsided. They held that the danger of the influenza epidemic was so grave that it was imperative to secure isolation for the patient (JAMA, 10/12/1918). The members of the APHA committee agreed in their report, saying that patients with influenza should to be kept in isolation. Because of the strain on facilities, only severe cases were to be hospitalized while mild influenza patients were to remain at home. The APHA also supported institutional quarantines to protect people from the outside world in establishments like asylums and colleges (JAMA, 12/21/1918). The use of institutional quarantines was applied to the many military training camps set up in the United States to prepare soldiers for war. These camps, with masses of men from throughout the country, were prime targets of huge influenza epidemics. The men were kept in strict isolation once ill and entire camps was often quarantined (JAMA, 4/12/1919). These measures were easily implemented in these camps where men were already committed to their country and the authority of the government.

Preventative Measures

The Committee of the American Public Health Association (APHA) issued a report outlining appropriate ways to pre vent the spread and reduce the severity of the epidemic. They noted first that the disease was extremely communicable and “spread solely by discharges from the nose and throats of infected persons.” They sought to prevent infection by breaking the channels of communication such as droplet infection by sputum control. They believed that infection occurred by the contamination of the hands and common eating and drinking utensils. Thus they called for legislation to prevent the use of common cups and to regulate coughing and sneezing. They wanted to initiate education programs and publicity on respiratory hygiene about the dangers of coughing, sneezing and the careless disposal of nasal discharges. They aimed to teach people the value of hand- washing before eating and the advantages of general hygiene (JAMA, 12/21/1918). Public Health Departments issued Flu Posters to educate the community and reduce the spread of infection. The members also noted that the response should vary according to the type of community and the living conditions. Measures were to be adapted to rural or metropolitan areas, with a centralized coordination to enforce compulsory reporting and canvassing for cases.

vent the spread and reduce the severity of the epidemic. They noted first that the disease was extremely communicable and “spread solely by discharges from the nose and throats of infected persons.” They sought to prevent infection by breaking the channels of communication such as droplet infection by sputum control. They believed that infection occurred by the contamination of the hands and common eating and drinking utensils. Thus they called for legislation to prevent the use of common cups and to regulate coughing and sneezing. They wanted to initiate education programs and publicity on respiratory hygiene about the dangers of coughing, sneezing and the careless disposal of nasal discharges. They aimed to teach people the value of hand- washing before eating and the advantages of general hygiene (JAMA, 12/21/1918). Public Health Departments issued Flu Posters to educate the community and reduce the spread of infection. The members also noted that the response should vary according to the type of community and the living conditions. Measures were to be adapted to rural or metropolitan areas, with a centralized coordination to enforce compulsory reporting and canvassing for cases.

Public Health agencies applied the principles of contagion to methods of hygiene and a regard for ventilation in their suggestions for reducing the spread of the illness and preventing disease. They held that well ventilated, airy rooms promoted well-being, (BMJ, 11/16/1918).

Preventative measures built upon the same ideas of transmission and the germ theory of disease. These ideas were practiced in the hospitals as special influenza wards for influenza patients were created and the number of beds per ward was decreased to reduce the transmission of the disease. Those with complications such as pneumonia were separated from the rest to prevent the others from progressing to this more fatal state (BMJ, 11/2/1918). Sheets were hung between the beds to mimic isolation in limited closed quarters to provide a cubicle for each patient. No patient was allowed to leave their bed until they were fever free for 48 hours. In the military camps, soldiers were instructed to eat 5 feet apart in the mess halls. Head to foot sleeping was also implemented to reduce the sharing of air space (JAMA, 4/12/1919). One camp used these ideas of prevention via ventilation and boasted of their results. They claimed their rampant influenza epidemic terminated once men were kept out in the open with sunlight or in open, airy halls and prevented from gathering (JAMA, 12/14/1918).

One of the key aspects of prevention was the use of disinfection and sterilization methods. The practical prevention guidelines utilized the recent developments made by Lister and others of the necessity antiseptic conditions. All bedding and rooms were to be periodically disinfected to kill whatever pathogen pervaded them. In naval ambulance trains this was executed by washing down the train with a weak izal antiseptic solution (BMJ, 11/23/1918). The produced sputum, thought to be riddled with the microbe, was to be destroyed. In one hospital the sputum cups were emptied and disinfected twice daily, while nasal discharges were collected in paper napkins. An antiseptic hand solution was placed

One of the key aspects of prevention was the use of disinfection and sterilization methods. The practical prevention guidelines utilized the recent developments made by Lister and others of the necessity antiseptic conditions. All bedding and rooms were to be periodically disinfected to kill whatever pathogen pervaded them. In naval ambulance trains this was executed by washing down the train with a weak izal antiseptic solution (BMJ, 11/23/1918). The produced sputum, thought to be riddled with the microbe, was to be destroyed. In one hospital the sputum cups were emptied and disinfected twice daily, while nasal discharges were collected in paper napkins. An antiseptic hand solution was placed

conveniently for those on duty in the influenza ward (JAMA, 4/12/1919). One French report also suggested that the staff of influenza wards should wear blouses inside the ward and remove them when leaving (BMJ, 11/2/1918). These disinfection procedures of prevention utilized scientific ideas of germ theory to reduce transmission.

The gauze mask was another prevention method using similar ideas of contagion and germ theory. In the United States it was widely accepted for use in hospitals among health care workers. The face masks consisted of a half yard of gauze, folded like a triangular bandage covering the mouth, nose and chin (BMJ, 11/2/19118). These gauze masks acted to prevent the infectious droplets from being expelled by the mouth and from the hands, contaminated with microbe from being put to the mouth. The barrier from the hands was thought to be more important than the barrier from the air. The mask was also worn in some regions by the general population. In San Francisco the gauze masks were made a requirement of the entire population in a trial ordinance. This was later expanded to include San Diego in December. This rhyme was a popular way to remind people of the ordinance.

Obey the laws

And wear the gauze Protect your jaws

From Septic Paws

They found that the mask wearing led to “a rapid decline in the number of cases of influenza,” (JAMA, 12/28/1918). A study in the Great Lakes, however, did not find such beneficial results. Mask wearing by hospital corps did not have an effect on the incidence of disease as 8% who used the mask developed infection while only 7.75% of non-mask wearers did (JAMA, Vol. 71, No. 26). Despite these results, the masks were commonly used by many in an effort to avoid the pandemic influenza disease.

Prophylaxis

The members of the APHA committee also suggested ways to increase the natural resistance to the illness. They stated that nervous and physical exhaustion should be avoided. People were encouraged to maintain proper rest, to get fresh air and maintain general hygiene. The French report also encouraged avoiding over-fatigue and exposure to the cold (BMJ, 11/2/1918). The Royal College of Physicians shared this opinion saying that the chilling of the body should be prevented by wearing warm clothing out of doors. They also claimed that good nourishment of food and drink was desirable, saying that chill and over-exertion…have evil consequences,” (BMJ, 11/16/1918). These methodologies unlike the preventative measures do not appear to have a strong scientific basis. Rather, they reflect common societal ideas about the wellness and the ability to fight infection. Thus to a degree, the medical and public health officials were still using common sense notions to combat this new infectious terror.

One method of preventing infection, however was more scientific, more elaborate and more controversial. This was the gargling and rinsing out of the nasopharynx with antiseptic solution.  Physicians held that since the disease was transmitted through the upper respiratory passages, it made sense to disinfected the nose and mouth to prevent infection. One method was to gargle with warm watermixed with chlorinated soda. A Dr. F. W. Alexander recommended electrolytic disinfection fluid as mouth wash for influenza to be gargled and sniffed up the nose (BMJ, 11/2/1918). Others gargled and sprayed the nasopharynx with a weak solution of carbolic acid and combined it with quinine to prevent infection (BMJ, 11/23/1918). A more serious method of cleansing and disinfecting the nasal spaces and upper air passages was suggested by Dr. James Bach. He advocated a powder of boric acid and sodium bicarbonate. The powder was to be blown into the nose which would then dissolve and by osmotic pressure induce mucus flow to wash the membranes (JAMA, 12/7/1918). This method has a scientific basis but little scientific proof of efficacy. They worked as well as some of the treatments invented to cure influenza which were based on scientific ideas but not scientific results. The APHA members believed that gargling had no value as they cleared out the protective mucus barrier to infection.

Physicians held that since the disease was transmitted through the upper respiratory passages, it made sense to disinfected the nose and mouth to prevent infection. One method was to gargle with warm watermixed with chlorinated soda. A Dr. F. W. Alexander recommended electrolytic disinfection fluid as mouth wash for influenza to be gargled and sniffed up the nose (BMJ, 11/2/1918). Others gargled and sprayed the nasopharynx with a weak solution of carbolic acid and combined it with quinine to prevent infection (BMJ, 11/23/1918). A more serious method of cleansing and disinfecting the nasal spaces and upper air passages was suggested by Dr. James Bach. He advocated a powder of boric acid and sodium bicarbonate. The powder was to be blown into the nose which would then dissolve and by osmotic pressure induce mucus flow to wash the membranes (JAMA, 12/7/1918). This method has a scientific basis but little scientific proof of efficacy. They worked as well as some of the treatments invented to cure influenza which were based on scientific ideas but not scientific results. The APHA members believed that gargling had no value as they cleared out the protective mucus barrier to infection.

The American Public Health Association committee members believed that the best way to prevent infection was through the use of vaccines. Vaccines could prevent or mitigate infection with influenza and the frequently fatal complications of the illness due to the influenza bacillus or strains of streptococci and pneumonococci. They believed that the current vaccines under development should be tested and administered if useful to prevent infection. The committee suggested the use of the experimental vaccines on susceptibles with equal subjects and controls and under proper scientific methodology. However, they acknowledged that the cause of the influenza was unknown and therefore an effective vaccine had no “scientific basis,” (JAMA, 12/21/1918). These public health officials shared the perceptions of the scientific and medical community of the influenzal disease and its origins.[2]

Public Health Emergency Management

Initially emergency response was focused on issues related to the Cold War and Russia. However, in the 1970’s the purpose away from civil defense and started to look at natural disasters and other general public health issues.

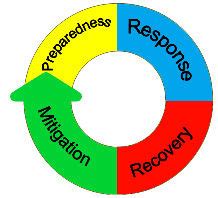

When considering emergency programs there are a total of 4 elements in the cycle as seen below in the graphic.

Most recently due to Ebola, Sars, Covid, H1N1 Bird Flu and Monkey Pox it is increasingly evident that the public health sector needs to adopt a better defined field of practice related to Public Health Emergency Management. In 2017 an article was published in the American Journal Of Public Health that outlined the steps for such a move and various aspects related to the development of the field of practice.

The authors stated that “Public Health Emergency Management (PHEM) is an emergent field of practice that draws on specific sets of knowledge, techniques, and organizing principles found in the fields of emergency management and public health that are necessary for the effective management of complex health events and emergencies with serious health impacts. Although concepts such as public health preparedness and global health security include significant components of PHEM, the various terms should not be conflated.”[3]

The authors also state that there are two principal pillars on which PHEM has been built: organizational and programmatic (i.e., industry) standards and the incident management system (IMS). In this class we will be reviewing various aspects of the two pillars that they identified.

01.05 Module 01 Discussion Forum-CDC Legal Authorities –Link to Canvas Site

For this discussion, you will be discussing the topic of various Federal Authorizations that are in place to address emergency response. Some of the authorities are in Federal Law and others are Executive Orders issued by the Presidents. As for Executive Orders by the President, the general rule is that they are reauthorized as each new President takes office, unless the new President determines not to renew it. However, in the area of emergency response they are usually renewed. You will respond to several prompts and then share your response with your group on a discussion forum.

Pre-Discussion Work

To begin this assignment, review the following resource which is a listing of the various legal authorities.

Centers for Disease Control’s list of selected Federal Authorities to control communicable diseases pertaining to public health emergencies.

https://www.cdc.gov/phlp/docs/ph-emergencies.pdf

Drafting Your Response

Next, prepare your forum post by creating a Google document. On your document, answer the following questions:

- What is your impression of the volume of materials and the various dates the authority was established?

- List at least three authorities that you did not expect to be on such a list?

- Specifically review the authorities under Control of Communicable diseases.

- Is there an authority in there that you found particularly interesting?

- What is your thoughts on Penalties for Violation of Quarantine Law 42 U.S.C. § 271?

Be sure to support your responses by referencing materials from this module, in addition to those presented on the World Toilet Day site. Also, once you have answered the questions, be sure to proofread what you wrote before you share it.

Discussing Your Work

To discuss your findings, follow the steps below:

Step 01. After you have finished writing and proofreading your responses, click on the discussion board link below.

Step 02. In the Discussion Forum, create a new thread and title it using the following format: Yourname and the topic of the discussion board.

Step 03. In the Reply field of your post, copy and paste the text of your composition from the Document you created.

Step 04. Add bolding, underlining, or italics where necessary. Also, correct any spacing and other formatting issues. Make sure your post looks professional.

Step 05. If you need to upload a document or image you can do so by clicking on the Upload image (photo image button) or Upload document (Document button) in the text editor and locating and selecting your document from your computer.

Step 06. When you have completed proofreading, fixing your post formatting, and attaching your file, click on the Post Reply button.

Legal Aspects of Public Health

As mentioned in the lecture it is important to be sure that you have legal authority to implement an action or regulations. Prior to the Anthrax scare and the concern for the use of Weapons of Mass Destruction in the early 2000, Idaho did not have the authority to quarantine or isolate to prevent the spread of communicable diseases. Listed below are the specific portions of Idaho Code that gave the State Board of Health and Welfare that authenticity. That same authority was also given to the Local Boards of Health for the 7 health districts in Idaho. However, when implementing such action an agency must always take into account concern for violating a persons Basic Constitutional Rights. Listed below are the amendments to the United States Constitution.

1st Amendment

It protects the freedom of religion, speech, and the press, as well as the right to assemble and petition the government.

Enacted on December 15, 1791

2nd Amendment

Protects the right to keep and bear arms.

Enacted on December 15, 1791

3rd Amendment

Prohibits the forced quartering of soldiers.

Enacted on December 15, 1791

4th Amendment

Prohibits unreasonable searches and seizures and sets out requirements for search warrants based on probable cause.

Enacted on December 15, 1791

5th Amendment

Sets out rules for indictment by a grand jury and eminent domain. In addition, it protects the right to due process and prohibits self-incrimination and double jeopardy.

Enacted on 12/15/1791

6th Amendment

Protects the right to a fair and speedy public trial by jury, including the right to be notified of the accusations, to confront the accuser, to obtain witnesses, and to retain counsel.

Enacted on December 15, 1791

7th Amendment

The seventh amendment provides for the right to a trial by jury in certain civil cases, according to common law. It was enacted on December 15, 1791.

8th Amendment

Prohibits excessive fines and excessive bail, as well as cruel and unusual punishment.

Enacted on December 15, 1791

9th Amendment

Asserts the existence of unremunerated rights retained by the people.

Enacted on 12/15/1791

10th Amendment

Limits the powers of the federal government to those delegated to it by the Constitution. It was enacted on December 15, 1791.

11th Amendment

Provides immunity to states from suits from out-of-state citizens and foreigners not living within the state borders. In addition, it lays the foundation for sovereign immunity. Enacted on February 7, 1795.

12th Amendment

This one revises presidential election procedures.

Enacted on June 15, 1804

13th Amendment

Congress passed the Thirteenth Amendment to abolish slavery and involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for a crime. It was enacted on December 6, 1865

14th Amendment

Defines citizenship and deals with post–Civil War issues. It was enacted on July 9, 1868.

15th Amendment

Prohibits the denial of suffrage based on race, color, or previous condition of servitude. It was enacted on February 3, 1870

16th Amendment

It allows the federal government to collect income tax.

Enacted on February 3, 1913

17th Amendment

It requires United States senators to be directly elected.

Enacted on April 8, 1913

18th Amendment

Establishes the Prohibition of alcohol (eventually repealed by the Twenty-first Amendment – see below).

Enacted on January 16, 1919

19th Amendment

Establishes women’s suffrage.

Enacted on August 18, 1920[4]

This is the listing of the Powers and Duties of the State Board of Health. I have highlighted that portion that speaks specifically to the right to quarantine and Isolate.

This is the section of Idaho Code that gives authority to the Local Boards of Health to quarantine and isolate:

Title 39 – HEALTH AND SAFETY

Chapter 4 – PUBLIC HEALTH DISTRICTS

Section 39-415 – QUARANTINE.

39-415. QUARANTINE. The district board shall have the same authority, responsibility, powers, and duties in relation to the right of quarantine within the public health district as does the state.

History:

[39-415, added 1970, ch. 90, sec. 7, p. 218; am. 1973, ch. 29, sec. 7, p. 56.]