10 Chapter 10- Public Health Response in Haiti to Cholera Epidemic

Cholera[1]

World Health Organization cased definition of Cholera Alert[2]

10.05 Discussion Forum -Cholera Refugee Camp-Link to Canvas Site

For this discussion, you will be looking at Cholera worldwide and activities associated with the disease. Cholera has been and continues to be a disease that plagues the world. Dr. John Snow is considered one of the founders of modern epidemiology, in part because of his work in tracing the source of a cholera outbreak in Soho, London, in 1854, which he curtailed by removing the handle of a water pump. It seems that where ever you find poor sanitation you will find cholera. For this discussion assume you work for the United States Public Health service and you have been assigned to the UN High Commissioners on Refugees to provide advise related to public health for a new refugee camp that is in the highlands of Ethiopia.

Background Information

Read the materials in Chapter 10 of the Textbook.

Discussion prompts:

Step 01. Please address the following prompts:

- What would be the top three actions you would advise related to the development of the new camp?

- How would you prioritize the actions and why

Discussing Your WorkTo discuss your findings, follow the steps below:Step 01. After you have finished writing and proofreading your responses, click on the discussion board link below.Step 02. In the Discussion Forum, create a new thread and title it using the following format: Yourname’s and the topic of the discussion board.

Step 03. In the Reply field of your post, copy and paste the text of your composition from the Document you created.

Step 04. Add bolding, underlining, or italics where necessary. Also, correct any spacing and other formatting issues. Make sure your post looks professional.

Step 05. If you need to upload a document or image you can do so by clicking on the Upload image (photo image button) or Upload document (Document button) in the text editor and locating and selecting your document from your computer.

Step 06. When you have completed proofreading, fixing your post formatting, and attaching your file, click on the Post Reply button.

WHO suspect case definitions for a cholera alert

a) Two or more people aged 2 years and older (linked by time and place) with acute watery diarrhoea and severe dehydration or dying from acute watery diarrhea from the same areas within one week of one another.

OR

b) One death from severe acute watery diarrhoea in a person at least 5 years old.

OR

c) One case of acute watery diarrhoea testing positive for cholera by rapid diagnostic test a in an area (including those at risk for extension from a current outbreak) that has not yet detected a confirmed case of cholera.

Key facts[3]

- Most of those infected will have no or mild symptoms and can be successfully treated with oral rehydration solution.

- A global strategy on cholera control, Ending Cholera: a global roadmap to 2030, with a target to reduce cholera deaths by 90% was launched in 2017.

- Researchers have estimated that each year there are 1.3 to 4.0 million cases of cholera, and 21 000 to 143 000 deaths worldwide due to cholera (1)

- Cholera is an acute diarrhoeal disease that can kill within hours if left untreated.

- Provision of safe water and sanitation is critical to prevent and control the transmission of cholera and other waterborne diseases.

- Severe cases will need rapid treatment with intravenous fluids and antibiotics.

- Oral cholera vaccines should be used in conjunction with improvements in water and sanitation to control cholera outbreaks and for prevention in areas known to be high risk for cholera.

Diagnosis and Detection[4]

It is almost impossible to distinguish a single patient with cholera from a patient infected by another pathogen that causes acute watery diarrhea without testing a stool sample. A review of clinical features of multiple patients who are part of a suspected outbreak of acute watery diarrhea can be helpful in identifying cholera because of the rapid spread of the disease.

While management of patients with acute watery diarrhea is similar regardless of the illness, it is important to identify cholera because of the potential for a widespread outbreak.

Isolation and identification of Vibrio cholerae serogroup O1 or O139 by culture of a stool specimen remains the gold standard for the laboratory diagnosis of cholera.

Cary Blair media is ideal for transport, and the selective thiosulfate–citrate–bile salts agar (TCBS) is ideal for isolation and identification. Reagents for serogrouping Vibrio cholerae isolates are available in all state health department laboratories in the U.S. Commercially available rapid test kits are useful in epidemic settings but do not yield an isolate for antimicrobial susceptibility testing and subtyping, and should not be used for routine diagnosis.

In many countries where cholera is not uncommon, but access to diagnostic laboratory testing is difficult, WHO recommends the following clinical definition be used for suspected cholera cases.

Suspected cholera case

- In areas where a cholera outbreak has not been declared: Any patient 2 years old or older presenting with acute watery diarrhea and severe dehydration or dying from acute watery diarrhea.

- In areas where a cholera outbreak is declared: any person presenting with or dying from acute watery diarrhea.

WHO also recommends the following definition for confirmed cholera cases.

Confirmed cholera case

A suspected case with Vibrio cholerae O1 or O139 confirmed by culture or PCR and, in countries where cholera is not present or has been eliminated, the Vibrio cholerae O1 or O139 strain is demonstrated to be toxigenic.

Rapid Tests

In areas with limited or no laboratory testing, the Crystal® VC dipstick rapid test can provide an early warning to public health officials that an outbreak of cholera is occurring. However, the sensitivity and specificity of this test is not optimal. Therefore, it is recommended that fecal specimens that test positive for V. cholerae O1 and/or O139 by the Crystal® VC dipstick always be confirmed using traditional culture-based methods suitable for the isolation and identification of V. cholerae.

Five Basic Cholera Prevention Steps[5]

If you live in or are visiting an area where cholera is occurring or has occurred, be aware of basic cholera facts and follow the five cholera prevention tips listed below. These tips will help you protect yourself and your family.

To prevent cholera, you should wash your hands often and take precautions to ensure your food and water are safe for use. The risk for cholera is very low for people visiting the areas listed below when these simple steps are followed:

Cholera is found in countries around the world but is extremely rare in the United States and other industrialized nations.

The following is a list of countries that have areas of active cholera transmission

- Africa: Benin, Cameroon, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Niger, Nigeria, Somalia, South Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia

- Asia: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Iraq, Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines, Syria, Yemen

- Americas: none

- Pacific: none

1. Make sure to drink and use safe water to brush your teeth, wash and prepare food, and make ice

- It is safe to drink and use bottled water with unbroken seals, and canned or bottled carbonated beverages.

- If bottled water is not available, use water that has been properly boiled, chlorinated, or filtered:

- Boiling is the most effective way to make water safe. If boiling, bring your water to a complete boil for at least 1 minute.

- If boiling is not possible, you can use a chlorine product (i.e., granules or product tablets) to make your water safe. To treat your water with chlorine granules or tablets, use one of the locally available treatment products and follow the instructions.

- If a chlorine treatment product is not available, you can treat your water with household bleach. Visit CDC’s Making Water Safe in an Emergency page for specific instructions on how to treat your water with household bleach.

- Always store your treated water in a clean, covered container.

- Clean food preparation areas and kitchenware with soap and safe water and let them dry completely before reuse.

- Piped water sources, drinks sold in cups or bags, and ice may not be safe. If you suspect your water may not be safe, boil or treat it with a chlorine product.

2. Wash your hands often with soap and safe water*

- Before, during, and after preparing food for yourself or your family

- After using the latrine or toilet

- After cleaning your child’s bottom

- Before and after caring for someone with cholera

Follow the five steps to washing hands the right way:

- Wet your hands with clean water.

- Apply soap to your hands and rub them together. Be sure to lather the back of your hands, between your fingers, and under your nails.

- Scrub your hands for at least 20 seconds.

- Rinse your hands well under clean water.

- Allow your hands to air dry or dry them with a clean towel.

* If proper handwashing resources are not available, wash your hands using water that is as clean as possible (e.g. that’s not visibly cloudy) from a safe source (e.g., an improved source like a borehole or protected spring).

Traveling to an area with cholera?

Visit a doctor or travel clinic to talk about cholera vaccination if you will be traveling to or living in an area of active cholera transmission.

Currently, the only cholera vaccine approved in the United States for use (Vaxchora, an oral vaccine for those 2-64 years of age) is not available. Three other oral cholera vaccines are approved by the World Health Organization (WHO) and may be available at your travel destination or if you are living outside of the United States.

3. Use latrines or bury your poop; do not poop in any body of water

- Use latrines or other sanitation systems, like chemical toilets, to dispose of poop.

- Wash hands with soap and safe water after pooping.

- Clean latrines and surfaces contaminated with poop using a solution of 1 part household bleach to 9 parts water.

What if I don’t have a latrine or chemical toilet?

- Poop at least 30 meters (approximately 100 feet) away from any body of water and then bury your poop.

- Dispose of plastic bags that contain poop by putting them in latrines or at collection points, if available. You can also bury them in the ground. Do not put plastic bags in chemical toilets.

- Dig new latrines or temporary pit toilets at least a half-meter (approximately 1 ½ feet) deep and at least 30 meters (approximately 100 feet) away from any body of water.

4. Cook food well (especially seafood), keep it covered, and eat it hot. Peel fruits and vegetables*

- Be sure to cook shellfish (like crabs and crayfish) until they are very hot all the way through.

- *Avoid raw foods other than fruits and vegetables that you have peeled yourself.

5. Clean up safely in the kitchen and in places where the family bathes and washes clothes

- Wash yourself, your children, diapers, and clothes, 30 meters (approximately 100 feet) away from drinking water sources.

2010 Haiti Cholera Outbreak and CDC Response[6]

Cholera Verified

On October 19, 2010, the Haitian Ministry of Public Health and Population (MSPP) was notified of a sudden increase in patients with acute watery diarrhea and dehydration. On October 21, the “Laboratoire National de Sante Publique” (National Public Health Laboratory) confirmed V. cholerae serogroup O1, biotype Ogawa, and the outbreak of cholera was publicly announced on October 22 1-4.

The rapid spread of cholera in Haiti sparked one of the best coordinated and documented responses to a cholera outbreak in modern public health 5. Because the outbreak was spreading rapidly and the initial case-fatality rate was high—meaning a high proportion of patients were dying— the Haitian Ministry of Public Health and Population and the U.S. government initially focused on five immediate priorities:

- Prevent deaths in health facilities by distributing treatment supplies and providing clinical training

- Prevent deaths in communities by supplying oral rehydration solution (ORS) sachets to homes and urging ill people to seek care quickly

- Prevent disease spread by promoting point-of-use water treatment and safe storage in the home, handwashing, and proper sewage disposal

- Conduct field investigations to define risk factors and guide prevention strategies

- Establish a national cholera surveillance system to monitor spread of disease

The top priority of any public health response is to save lives and control the spread of disease.

Coordination of Response

CDC’s response to the outbreak was coordinated through its Emergency Operations Center in Atlanta, Georgia, and CDC experts across the agency were deployed to Haiti and the Dominican Republic to provide in-country assistance. Among those involved in the response were medical officers, epidemiologists, laboratory scientists, environmental health specialists, communication specialists, public health advisors, planners, information technology specialists, and support staff. The Division of Global HIV and TB, which opened CDC’s first office in Haiti in 2002 to support the Government of Haiti in addressing its HIV/AIDS epidemic, was critical in the coordination of the response.

Rapid Response

Within days, the Haitian Ministry of Public Health and Population (MSPP), with technical assistance from CDC and its partners, established a national surveillance system to track cases of the disease. MSPP, CDC, and partners quickly developed cholera treatment and prevention materials and trained more than 500 health care workers across the country. The number of workers trained swelled to more than 10,000 a few months into the outbreak.

U.S. government agencies including CDC helped to leverage in-country resources, most notably the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and non-governmental organizations, to increase the number of cholera treatment centers and oral rehydration points. These efforts helped reduce the initial mortality rate (number of patients dying) from nearly 4% of all cases to less than 1%, saving an estimated 7,000 lives.

Within the first week of the outbreak, MSPP and CDC quickly provided Haitian news outlets with five basic prevention messages pdf icon[PDF – 2 pages] advising Haitians how to protect themselves from cholera. These messages were quickly supported with instructions on how to treat cholera and other forms of acute watery diarrhea by preparing and providing oral rehydration solution to all people early in the course of their illness; diagnosis and testing guidelines; clinical presentation and management guidance; and healthcare provider training materials. CDC translated materials into French, Haitian Creole, and Spanish.

Community Health Workers

Community health workers (CHWs) play an essential role in providing healthcare services and education at the community level, particularly in rural areas. In collaboration with MSPP, CDC quickly developed CHW training materials on cholera education and prevention and trained 24 master trainers from MSPP and partners representing all 10 departments of Haiti. Master trainers then trained more than 1,100 CHWs using CDC materials from March to June 2011. This training, which emphasized that “no one need die from diarrheal disease,” contributed to building Haitian capacity in managing cholera.

Other key elements of the response included CDC efforts to improve water, sanitation, and hygiene throughout the country. CDC, working with UNICEF and Haiti’s National Department of Drinking Water and Sanitation, helped establish water chlorination programs to increase access to safe water for drinking, handwashing, and cleaning. CDC and partners also conducted water testing for V. cholerae 6 and provided water storage vessels, soap, and large quantities of emergency water treatment supplies for homes and piped water systems.

But as evidenced by the cholera outbreak, much remains to be done in Haiti. Cholera will ultimately be controlled when municipal and rural water systems separate drinking water from sewage as was done in countries in Latin America after the 1991 cholera epidemic 7.

Cholera Outbreak in Dadaab Refugee Camp, Kenya — November 2015–June 2016[7]

What is added by this report?

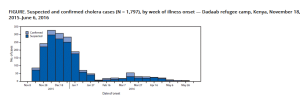

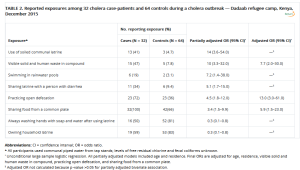

During November 18, 2015–June 6, 2016, the largest cholera outbreak (1,797 cases; attack rate 5.1 per 1,000) in the history of Dadaab refugee camp in Kenya occurred. Significant risk factors included living in a compound where open defecation, visible human and solid waste, and eating from a shared plate were common. Chlorine levels in water were below standard, and handwashing facilities were insufficient.

What are the implications for public health practice?

Improvements to water and sanitation, expansion of capacity for community outreach, and enhanced camp security and disease surveillance systems in Dadaab camp and the surrounding area are urgently needed.

Public Health Response

Cholera treatment centers were established by Médecins Sans Frontiéres and the International Rescue Committee, and active surveillance for cases of acute watery diarrhea was enhanced. A health promotion and hygiene campaign was conducted, primarily through mobilization of community health workers (from 168 during the first few weeks of the outbreak to 286) and hygiene promoters and use of media networks, especially radio. Frequent coordination meetings were held among stakeholders to provide updates and revise recommendations. Water from boreholes was chlorinated, soap was distributed, and bedding and latrine disinfection in affected households was carried out. WASH partners were advised to maintain adequate chlorination levels, install additional tap stands and latrines (especially in unofficial settlement areas), and install additional handwashing facilities in schools, eateries, and marketplaces.

Discussion

All subcamps were affected, but the highest rates occurred in the two largest subcamps. These two areas had poorer water drainage and were in proximity to food markets where persons from areas with active cholera transmission interact. These factors might have contributed to the large number of cases and high attack rates in these areas. Furthermore, in these subcamps, large numbers of housing structures were outside the official boundaries of the camp, in areas that had poorer water and sanitation infrastructure. Inadequate residual chlorine levels in drinking water and the presence of standing bodies of water used for swimming and bathing suggest possible waterborne transmission routes. Reported infection of multiple household members and spatial case clustering among residential blocks suggest household transmission or common exposures to a contaminated food or water source.

Limited promotion of hygiene messaging during the early weeks of the outbreak could also have increased vulnerability to cholera transmission. Sustained and intensive hygiene promotion and WASH interventions in the most affected blocks were also recommended.

WHO Preventing epidemics and pandemics[8]

The number of high-threat infectious hazards continues to rise; some of these are re-emerging and others are new. While outbreaks of vaccine-preventable infectious diseases, such as meningococcal disease, yellow fever and cholera, can have disastrous effects in areas with limited health infrastructure and resources, and where timely detection and response is difficult.

WHO develops global strategies for the prevention and control of epidemic-prone diseases, such as yellow fever, cholera and influenza. With partners from a wide range of technical, scientific and social fields, WHO brings together all globally available resources to counter these high-threat infectious hazards and scale these strategies to regional and country levels.

Flagship global strategies include:

- the Eliminate Yellow Fever Epidemics strategy 2017- 2026;

- Ending Cholera: a Global Roadmap to 2030; (Emphasis Added)

- the Pandemic Influenza Preparedness (PIP) Framework; and

- the Global Strategy for Influenza 2018-2030.

WHO is also the secretariat for the governance of global emergency stockpiles, including the International Coordinating Group on Vaccine Provision, which manages and coordinates the provision of emergency vaccine supplies and antibiotics to countries during major outbreaks.

- https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cholera ↵

- https://medicalguidelines.msf.org/en/viewport/CHOL/english/2-2-cholera-alerts-23448711.html ↵

- https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cholera ↵

- https://www.cdc.gov/cholera/diagnosis.html ↵

- https://www.cdc.gov/cholera/preventionsteps.html ↵

- https://www.cdc.gov/cholera/haiti/2010-outbreak-response.html ↵

- https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/wr/mm6734a4.htm ↵

- https://www.who.int/activities/preventing-epidemics-and-pandemics ↵