13 Chapter 13 Debriefing and After Action Reports, Community Assessment for Public Health Emergency Response (CASPER)

Types of Debriefing Following Disasters

The aim of all disaster mental-health management, including any type of debriefing, should be the humane, competent, and compassionate care of all affected. The goal should be to prevent adverse health outcomes and to enhance the well-being of individuals and communities. In particular, it is vital to use all appropriate endeavors to prevent the development of chronic and disabling problems such as PTSD, depression, alcohol abuse, and relationship difficulties. Debriefings are a type of intervention that are sometimes used following a disaster or other traumatic event.

Different Types of Debriefing

- Operational debriefing is a routine and formal part of an organizational response to a disaster. Mental-health workers acknowledge it as an appropriate practice that may help survivors acquire an overall sense of meaning and a degree of closure.

- Psychological or stress debriefing refers to a variety of practices for which there is little supportive empirical evidence. It is strongly suggested that psychological debriefing is not an appropriate mental-health intervention.

- Critical Incident Stress Debriefing (CISD) is a formalized, structured method whereby a group of rescue and response workers reviews the stressful experience of a disaster. CISD was developed to assist first responders, such as fire and police personnel; it was not meant for the survivors of a disaster or their relatives. CISD was never intended as a substitute for therapy. It was designed to be delivered in a group format and meant to be incorporated into a larger, multi-component crisis intervention system labeled Critical Incident Stress Management (CISM). CISM includes the following components: pre-crisis intervention; disaster or large-scale demobilization and informational briefings (town meetings); staff advisement; defusing; CISD; one-on-one crisis counseling or support; family crisis intervention and organizational consultation; follow-up and referral mechanisms for assessment and treatment, if necessary.

Currently, many mental-health workers consider some form of stress debriefing the standard of care following both natural (earthquakes) and human-caused (workplace shootings, bombings) stressful events. Indeed, the National Center for PTSD’s Disaster Mental Health Guidebook (which is currently being revised) contains information on how to conduct debriefings.

However, recent research indicates that psychological debriefing is not always an appropriate mental-health intervention. Available evidence shows that, in some instances, it may increase traumatic stress or complicate recovery. Psychological debriefing is also inappropriate for acutely bereaved individuals. While operational debriefing is nearly always helpful (it involves clarifying events and providing education about normal responses and coping mechanisms), care must be taken before delivering more emotionally-focused interventions.

A recent review of eight debriefing studies, all of which met rigorous criteria for being well-controlled, revealed no evidence that debriefing reduces the risk of PTSD, depression, or anxiety; nor were there any reductions in psychiatric symptoms across studies. Additionally, in two studies, one of which included long-term follow-up, some negative effects of CISD-type debriefings were reported relating to PTSD and other trauma-related symptoms (1).

Therefore, debriefings as currently employed may be useful for low magnitude stress exposure and symptoms or for emergency care providers. However, the best studies suggest that for individuals with more severe exposure to trauma, and for those who are experiencing more severe reactions such as PTSD, debriefing is ineffective and possibly harmful.

The question of why debriefing may produce negative results has been considered and hypotheses have been formulated. One theory connects negative outcomes with heightened arousal in the early posttrauma phase and in long-term psychopathology (2,3). Because verbalization of the trauma in debriefing is limited, habituation to evoked distress does not occur. The result may be an increase rather than a decrease in arousal. Any such increased distress caused by debriefing may be difficult to detect in a group setting. Thus, attempting to use debriefing to override dissociation and avoidance in the immediate posttrauma phase may be detrimental to some individuals, particularly those experiencing heightened arousal. Another consideration is that the boundary between debriefing and therapy is sometimes blurred (e.g., challenging thoughts), which may increase distress in some individuals (3). Finally, those facilitating the debriefing sessions frequently are unable to adequately assess individuals in the group setting. They may erroneously conclude that a one-time intervention is sufficient to prevent further symptomatology.

Practice guidelines on debriefing formulated by the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies conclude there is little evidence that debriefing prevents psychopathology. The guidelines do recognize that debriefing is often well received and that it may help (1) facilitate the screening of those at risk, (2) disseminate education and referral information, and (3) improve organizational morale. However, the practice guidelines specify that if debriefing is employed, it should:

conclude there is little evidence that debriefing prevents psychopathology. The guidelines do recognize that debriefing is often well received and that it may help (1) facilitate the screening of those at risk, (2) disseminate education and referral information, and (3) improve organizational morale. However, the practice guidelines specify that if debriefing is employed, it should:

- Be conducted by experienced, well-trained practitioners

- Not be mandatory

- Utilize some clinical assessment of potential participants

- Be accompanied by clear and objective evaluation procedures

The guidelines state that while it is premature to conclude that debriefing should be discontinued altogether, “more complex interventions for those individuals at highest risk may be the best way to prevent the development of PTSD following trauma.”[1]

After Action Reports From World Health Organization

(© World Health Organization 2019

Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-

ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo) https://extranet.who.int/iris/restricted/bitstream/handle/10665/311537/WHO-WHE-CPI-2019.4-eng.pdf;jsessionid=0865EFC97FDAD4875328AE37F16F558C?sequence=1[2]

13.05 Discussion Forum After Action Reports-Link to Canvas Site

For this discussion, you will review the World Health Organization Guide contained in the textbook

Pre-Discussion Work

To begin this assignment, review the following resources:

- Read the portion of the textbook that contains the World Health Organization Guide

Drafting Your Response

Next, prepare your forum post by creating a document. On your document, respond to the following prompts:

- Have you ever participated in a debrief session after an event.

- Which element of the 4 types of After Action Reports might have been used in the reports that were shown in the lecture – The Las Vegas situation and the San Diego Situation? Why do you believe that the entities selected this type of AAR method.

- What is it about the AAR process that you find most interesting?

Be sure to support your responses by referencing materials from this module. Also, once you have answered the questions, be sure to proofread what you wrote before you share it.

Discussing Your Work

To discuss your findings, follow the steps below:

Step 01. After you have finished writing and proofreading your responses, click on the discussion board link below.

Step 02. In the Discussion Forum, create a new thread and title it using the following format: Yourname’s and the topic of the discussion board.

Step 03. In the Reply field of your post, copy and paste the text of your composition from the Document you created.

Step 04. Add bolding, underlining, or italics where necessary. Also, correct any spacing and other formatting issues. Make sure your post looks professional.

Step 05. If you need to upload a document or image you can do so by clicking on the Upload image (photo image button) or Upload document (Document button) in the text editor and locating and selecting your document from your computer.

Step 06. When you have completed proofreading, fixing your post formatting, and attaching your file, click on the Post Reply button.

1.1 PURPOSE OF THE GUIDANCE FOR AAR AND AAR TOOLKITS

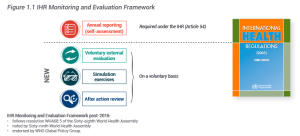

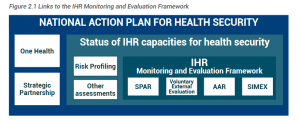

The World Health Organization (WHO) developed this guidance document and the accompanying toolkits to assist Member States in planning, preparing and conducting after action reviews (AARs) for collective learning and operational improvement after a public health response.The AAR is one component of the International Health Regulations (IHR) (2005) Monitoring and

Evaluation Framework, as shown in Figure 1.1.

1.1 AUDIENCE FOR THE GUIDANCE FOR AAR AND AAR TOOLKITS

The guidance for after action review (AAR) and AAR toolkits are meant for public health practitioners who are planning for an AAR to review actions taken in response to an event of public health concern. These practitioners may include staff of ministries of health, government officials from other sectors, and staff of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), international organizations, and WHO partner agencies.

Planners of AARs should bear in mind that each ministry, agency or organization is different. The principles presented in this guide should be adapted to the institutional culture, practice and needs around which the review is taking place.

1.2 STRUCTURE OF THE GUIDANCE FOR AAR AND AAR TOOLKITS

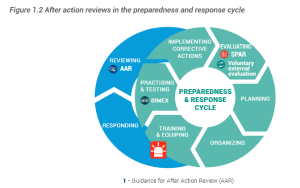

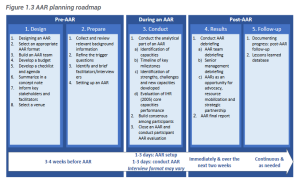

This guide provides a roadmap for AAR implementation (Figure 1.3). It is structured to follow the steps

needed for a successful AAR, including designing, preparing, conducting, and following up on an AAR.

Figure 1.3 AAR planning roadmap

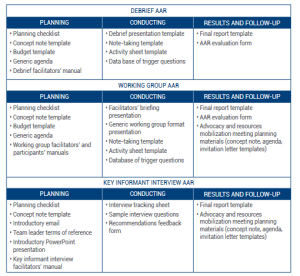

Accompanying this guide are several toolkits containing materials to support the planning of each step of an AAR. The detailed contents of all the toolkits are provided in Annex 2 of this document. The toolkits comprise the following:

• templates for developing, conducting and following up on an AAR;

• a checklist to support the step-by-step planning and implementation of an AAR;

• tailored guidance for facilitators;

• sample PowerPoint presentations to be used when conducting an AAR;

• a database of trigger questions.

2. INTRODUCTION TO AN AAR 2.1 WHAT IS AN AAR?

An AAR is a qualitative review of actions taken in response to an event of public health concern. An AAR is a means of identifying and documenting best practices and challenges demonstrated by the response to the event. An AAR seeks to identify:

• actions that need to be implemented immediately, to ensure better preparation for the next event;

• medium- and long-term actions needed to strengthen and institutionalize the necessary capabilities

of the public health system.

An AAR is designed to be flexible. It can be adapted to fit the event under review, and the organization and systems involved. Its success hinges on the ability to bring relevant response stakeholders together in an environment where they can analyse actions taken during the response in a critical and systematic fashion, and identify areas for improvement.

Stakeholders involved in preparedness activities relevant to the event under review can also be invited to an AAR to assess the impact of preparedness on the response.

AARs are not intended to assess individual performances or competences, but rather to identify functional challenges that must be addressed, and best practices to be maintained.

An AAR offers participants an opportunity to translate their experiences from the response into actionable roadmaps or plans, which should then be incorporated into national planning cycles (for example, the health sector plan, the humanitarian response plan, or the national action plan for health security).

AARs can vary in scope and format, but all AARs should involve:

• a structured review of response activities;

• an exchange of ideas and an in-depth analysis of what happened;

• identification of what can be addressed immediately;

• identification of what can be done in the longer term to improve responses to the next event.

While various quantitative and qualitative evaluation methods can be used after a response, the added value of an AAR is its focus on collective learning and experience sharing, with emphasis on the knowledge of stakeholders. One way in which an AAR can add value is by turning tacit knowledge into learning, and building trust and confidence among team members. In this way, AARs can become a key aspect of an organization’s internal system of learning and quality improvement, and can contribute to strengthening the capacity at the organization and country levels.

Furthermore, under the IHR (2005), the sharing of AAR results can reassure other countries’ stakeholders, citizens and the global public health community that commitments to IHR are strong, and that measures are being taken to address any identified gaps.

The systematic implementation of activities or recommendations identified through an AAR across a

ministry, or between sectors, communities, partners and other stakeholders, can help drive improvement.

AARs should ideally be conducted as soon as possible after an event or outbreak is declared over by the ministry of health or other authorized entity (or within three months). For protracted crises, multiple AARs can be conducted after each major phase or intervention. Similarly, for large-scale emergencies that involve many different capacities, separate AARs can be conducted for each major component of the response.

Generally, an AAR can be conducted following a response to any type of hazard, as described in the WHO Emergency Response Framework (1) (see Annex 3 on classification of hazards).

Whilst the AAR methodology described in this document can be used for any response, a specific guidance to conduct an AAR following the response to emergencies that were not caused by biological hazards can be found in Annex 4. This guidance can help the health sector to conduct an AAR to review its specific contribution to the multisectoral response and coordination.

2.2 AAR AND IHR MONITORING AND EVALUATION FRAMEWORK

The World Health Organization uses AARs as part of the IHR Monitoring and Evaluation Framework. This framework was developed in 2016 following the recommendation of the Review Committee on Second Extensions for Establishing National Public Health Capacities and on IHR Implementation (2). The committee recommended that:

States Parties should urgently … implement in-depth reviews of significant disease outbreaks and public health events. This should promote a more science- or evidence-based approach to assessing effective core capacities under “real-life” situations.

AARs focus on analysing a real-life event, providing a realistic assessment of the ability to implement IHR core capacities.

The IHR Monitoring and Evaluation Framework comprises a mixed approach of qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis, as well as desk reviews and functional assessments of capacities for prevention, preparedness, detection and response. It has four components, one of which – State Party self-assessment annual reporting (SPAR) – is obligatory. The other three components – the voluntary external evaluation, the AAR, and the simulation exercises – are voluntary (see Figures 1.1 and 2.1).

The voluntary instruments complement the mandatory SPAR in that they provide a more detailed, comprehensive picture of Member State capacity under the IHR (2005). The SPAR and the voluntary external evaluation are based on quantitative metrics and are aimed at evaluating core capacities. AARs and simulation exercises are aimed at gauging the functional status of those core capacities. All four can inform monitoring and evaluation of the implementation, preparedness, and operational readiness of the national action plan for health security, and can guide for corrective actions (testing and strengthening).

The SPAR can serve to measure the current status of IHR capacities development, provide annual monitoring of progress in implementing the national action plan for health security, and can also inform and provide context while developing an AAR or a simulation exercise.

The voluntary external evaluation can measure the current status of IHR capacities for health security, and guide – with the support of external expertise – the priority actions required to strengthen capacities. The voluntary external evaluation can also inform an AAR and a simulation exercise if conducted before.

Combining the results of each assessment provides a detailed, comprehensive reflection of the status and

functionality of a country’s capacity to prepare, prevent, detect and respond to public health emergencies.

These findings can also be combined with the results of other assessments and risk profiling exercises

to provide an even more detailed evaluation of the functional status of IHR capacities.

The evaluation findings of one or all components can serve as part of the basis for countries to develop and implement national multisectoral action plans using a “One Health” approach. These plans translate the priority recommendations of the various evaluations into actions for capacity-building to strengthen preparedness and response systems and to ensure that countries are operationally ready for public health risks and events.

Figure 2.1 Links to the IHR Monitoring and Evaluation Framework

The country implementation guidance on AARs and simulation exercises under the IHR (2005) Monitoring and Evaluation Framework, published by WHO, provides strategic and specific information on the criteria for initiating an AAR; guidance for developing recommendations and following up on implementation of activities proposed by participants; and guidance on sharing outputs through a reporting template (3).

2.3 WHAT IS THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN AN AAR AND A JOINT OPERATIONAL REVIEW?

The WHO Health Emergencies Programme supports the use of different types of reviews to assess the capacities and performance of WHO, Member States, and international partners to respond to health emergencies. Some of these reviews take place during an emergency to inform course correction or delivery against agreed response plans.

An AAR is a component of the IHR Monitoring and Evaluation Framework and is driven by Member States. In contrast, a joint operational review is a WHO-led process that focuses on international efforts by WHO and its partners to support ministries of health in responding to public health events or outbreaks.

The overall objective of a joint operational review is to ensure that the efforts and resources of WHO and its partners are aligned with the health emergency response plan. This involves reviewing the response against the strategic objectives within the response plan.

The joint operational review enables the integration of learning and corrective measures for current responses and where applicable future responses.

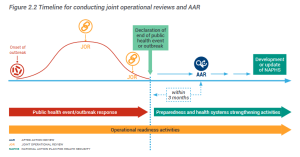

As indicated in Figure 2.2, joint operational reviews are conducted during the response to public health events or outbreaks, or at the end of the response. The AAR is conducted immediately after the public health event or outbreak is officially declared over by the ministry of health or other relevant authority.

Figure 2.2 Timeline for conducting joint operational reviews and AAR

2.4 WHAT ARE THE OBJECTIVES OF AN AAR?

An AAR is a review of all actions taken during the response to an event. The review aims to identify capacities in place before the response, any challenges that came to light during it, the lessons identified, and any best practices observed during the response, including the development of new capacities.

AARs generally focus on contrasting the actions undertaken as part of the response with the strategies, plans and procedures describing how action should have been taken. It assesses whether there was any difference between these, and seeks to assess the impact (positive or negative) of any deviation from planned actions.

There are three phases common to all AARs:

1. Objective observation: establish how actions were actually implemented, rather than how they would ideally have happened according to existing plans and procedures.

2. Analysis of gaps/best practices and contributing factors: identify gaps between planning and practice; analyse what worked and what did not work, and why.

3. Identification of areas for improvement: identify actions to strengthen or improve performance, and determine how to follow up on them.

2.5 WHAT ARE THE BENEFITS OF CONDUCTING AN AAR?

The benefits of conducting an AAR are as follows.

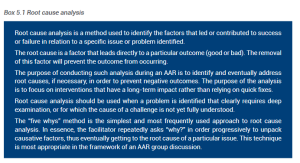

• Ensures critical thinking around the event. AARs use root cause analysis (Box 5.1) to assess the

underlying factors that led to any failures and successes encountered during the response.

• Builds consensus on issues for follow-up. Because team members work together during an AAR to identify challenges and best practices, the review creates consensus around actions necessary to prevent the next event and improve the next response.

• Allows documentation of lessons learned. AARs enable quick identification and documentation of lessons that can be applied to future events. This means team members can apply those lessons straight away.

• Allows cross-sectoral learning. As responses to many complex events (for example, outbreaks of cholera or viral haemorrhagic fever, earthquakes) involve more stakeholders than just those in the health sector, participants in the AAR can come from multiple sectors involved in the response. These might include animal health departments, hospital management boards, security authorities, and representatives of civil society. This can result in additional lessons being identified across sectors, bringing together new perspectives and strengthening relationships and coordination across sectors.

• Allows advocacy for support. An AAR report can be used as an advocacy tool for domestic

financing for public health systems, or for financial or technical support from partners.

• Builds capacity for preparedness and response. Gaps and best practices identified in the AAR can be respectively addressed for improvement, and documented and institutionalized.

2.6 WHEN SHOULD AN AAR BE CARRIED OUT?

AARs should be considered after a response to any event with public health significance.

The ideal timing for an AAR is within three months of the official declaration of the end of the event by the ministry of health in collaboration with WHO, when response stakeholders are still present and have clear memories of what happened (see Figure 2.2).

However, the same methodology can be applied while an event is still continuing; for example, during protracted responses as a form of real-time analysis, or to cover a specific period or phase of the response.

3.1 DESIGNING AN AAR

3. BEFORE AN AAR

The first phase of implementing an AAR is to establish its objectives and scope. These elements determine most of the other preparations, such as who should participate and what is needed in terms of facilitation, budget and format for the review.

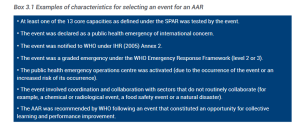

3.1.1 Select the response to review

Conducting an AAR should be considered part of routine emergency management procedures. While it is useful to review all emergency responses, the ability to do so may be limited by time and resource constraints. When this is the case, some characteristics of particular emergency responses should be considered as the basis for triggering an AAR. Box 3.1 gives examples of possible characteristics to consider.

Box 3.1 Examples of characteristics for selecting an event for an AAR

3.1.2 Define the specific objectives of an AAR

The objectives of an AAR may differ between countries and reviews. An early agreement on objectives

should be one of the first steps of planning an AAR. Common objectives for AARs include:

• assessing the functional capacity of existing systems to prepare, prevent, detect and respond to a public health event;

• identifying challenges and best practices encountered during the response;

• documenting and sharing experiences of response stakeholders;

• identifying practical actions for improving existing capacities and capitalizing on best practices;

• improving preparedness, readiness and response plans.

It will also be important to agree on how widely the results of an AAR will be shared. It is recommended that they are shared as widely as possible, including between countries without compromising the usefulness of the review. This is in order to:

• share lessons, experiences, examples and models;

• advocate for support for preparedness and readiness actions.

3.1.3 Define the scope of an AAR

The scope of an AAR will inform the profile of participants, the AAR format and trigger questions, and the

duration of the review.

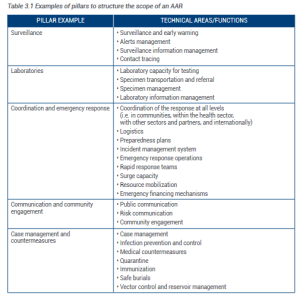

Most AARs use a format with a small number of “pillars” (five or six). These pillars are broad technical categories that combine several specific technical areas or functions and are used to structure the review. Typical pillars include surveillance; laboratories; coordination and emergency response; communication and community engagement; and case management and countermeasures. Pillars might also be chosen in order to highlight specific technical areas (for example, vector control or safe burials), depending on the types and magnitude of the challenges faced during the outbreak.

Table 3.1 provides examples of pillars and the associated key functions or technical areas to be considered when defining the scope of the AAR. Given the wide range of events that can be reviewed by an AAR and the specific context of any given response, AAR planners can consider additional technical areas or functions that are not included in the table.

Table 3.1 Examples of pillars to structure the scope of an AAR

The following parameters are examples of technical areas that could be used to define the focus of

the AAR:

• technical areas in which challenges were encountered during the response;

• technical areas that do not regularly benefit from performance analysis;

• technical areas that require frequent and deliberate improvement during “peacetime” because of their importance to the overall success of any response;

• technical areas that have been identified as requiring additional assessment by other monitoring

and evaluation activities (for example, simulation exercises).

The structure of the incident management system can also be used to define the scope of the AAR, if

an incident management system was used for the response.

The scope should also define the period of the emergency under review. For longer events (those

lasting more than one year) the AAR should cover the most acute period of the event.

Senior management should be part of the planning. Their firm agreement on the scope and objectives is needed in order to ensure commitment to active and accountable follow-up of the recommendations resulting from the AAR. Box 3.2 presents an example scope for a Lassa fever outbreak.

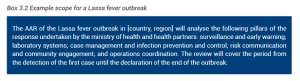

Box 3.2 Example scope for a Lassa fever outbreak

3.1.4 Identify stakeholders

A diversity of opinions is key to the success of an AAR; this can be achieved by ensuring the participation of a wide range of stakeholders. Once the scope has been defined, the AAR planner should identify appropriate stakeholders involved in the technical areas or functions of the response covered by the review. Contributions should be invited from stakeholders within the ministry of health, partner organizations and agencies that were involved in those technical areas.

For example, if the review is focused primarily on operational or field-level implementation, participants should include practitioners or technical staff who implemented response measures during the event, including those at local or community and regional levels. In contrast, if the review is focused on policy- or decision-making, it may be more relevant to involve policy- or decision-makers, and other senior management officials or stakeholders from the health sector and other sectors, ensuring that there is representation from different administrative levels (local to national).

Depending on the scope of the review and the magnitude of the event, gathering a wide participation of stakeholders from both technical and managerial roles should always be considered.

If an incident management system was set up for the response, it is crucial that the team gathered for the incident management system participates in the AAR.

In addition to actors from within the health sector at all levels, AAR planners should consider inviting other stakeholders. Some might be asked to participate in the discussion, whilst others might prefer to come as observers. These could include:

• municipality or local government authorities;

• community groups or other beneficiaries;

• representatives of academia;

• national and international partners who took part in the response (such as NGOs, United Nations agencies, or Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network (GOARN) partners);

• representatives of the private sector, including private hospitals or clinics, private laboratories, pharmaceutical companies and logistics providers;

• representatives of other sectors, such as the ministry of environment, the ministry of agriculture and civil protection;

• parliamentary health committees.

In addition, it is strongly advised that financial partners (both local and international) be involved in the

AAR process. These partners can be engaged in two ways.

• Through participation in the AAR itself and taking part in discussions and group work in the

“coordination” pillar, as resource mobilization will be one of the topics addressed in this pillar.

• By inviting them to an advocacy and resources mobilization meeting that can be held on the last day of the AAR or immediately after. During such a meeting, the ministry of health will present the key findings from the AAR and highlight funding gaps to the financial partners.

3.2 SELECT THE APPROPRIATE AAR FORMAT

WHO can provide tools and resources to conduct four formats of an AAR:

• debrief;

• working group;

• key informant interview;

• mixed-method.

Factors affecting format selection include location and number of participants, cultural context, the

complexity of the health event, and the resources required to conduct the AAR.

The rest of this section discusses the four different formats of an AAR and outlines the guidance and

tools available to assist those planning and implementing the AAR (see also Annex 5).

3.2.1 Debrief AAR

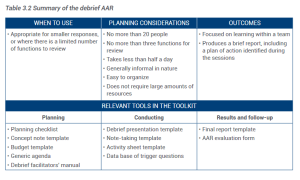

The debrief AAR is the simplest type of AAR. It is a facilitator-led discussion held over less than half a day, involving a small group and a plenary review of a limited number of functions. A debrief AAR tends to be fairly informal and focuses on the specific operations of a single team. The scope is generally narrow, allowing for focused learning outcomes. The debrief AAR is summarized in Table 3.2.

Table 3.2 Summary of the debrief AAR

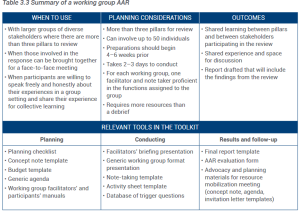

3.2.2 Working group AAR

A working group AAR is an interactive, structured methodology based on group exercises, plenary discussions and interactive facilitation techniques. It blends group work (in groups of 6–12 people) and plenary sessions. Each working group corresponds to a particular pillar of the response (for example, surveillance, case management).

Regular plenary sessions allow shared learning, consensus building and validation of recommendations between technical working groups. These sessions also lead to greater understanding of the interdependency between disciplines and response stakeholders. The working group format can involve a large, diverse group of participants (more than 20). This format is summarized in Table 3.3.

Table 3.3 Summary of a working group AAR

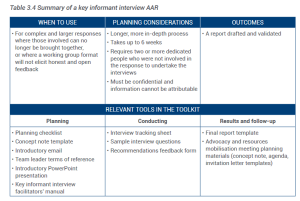

3.2.3 Key informant interview AAR

A key informant interview AAR consists of a longer, more in-depth review of an event. It includes research into background materials, such as peer-reviewed literature, media reports and grey literature. The research is followed by semistructured interviews and short focus group discussions in which key informants are encouraged to provide honest feedback on their experiences. Feedback can also be gathered through surveys sent to those involved in the response.

The survey results can be used to triangulate the common points of information gathered in the interviews and focus groups. Findings are analysed and synthesized into a succinct report that includes key recommendations. This report is then shared with those involved in the process for validation.

The AAR lead and interviewers should analyse, contrast and consolidate the results of individual interviews and build consensus among AAR participants about the findings and recommendations. This can be done at a final meeting where the results are shared and discussed.

The key informant interview AAR includes a commitment to confidentiality and non-attribution. This format is summarized in Table 3.4.

Table 3.4 Summary of a key informant interview AAR

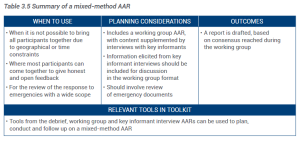

3.2.4 Mixed-method AAR

A mixed-method AAR approach blends the formats of the debrief, working group and key informant interview AARs. This approach can be used to review the response to emergencies for which it might not be possible to bring responders together for a working group format.

Key informant interviews should be undertaken before the group work. The results of these interviews can then be used to inform group discussions. Finally, results from both processes are synthesized into a report for validation. This format is summarized in Table 3.5.

Table 3.5 Summary of a mixed-method AAR

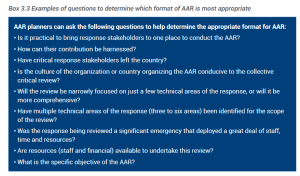

It is important to note that AAR formats are not set in stone, and they may need to be refined to fit the culture and practice of the institution, organization or agency undertaking the review.

Box 3.3 gives examples of questions that can be applied when deciding which format of AAR to use.

Box 3.3 Examples of questions to determine which format of AAR is most appropriate

3.3 BUILD AN AAR TEAM

The size and roles of the team will depend on the AAR format adopted, and may include the following.

• Overall AAR lead. The lead initiates the AAR and is responsible for planning and conducting it. The AAR lead should liaise with senior management, WHO and partners as needed on the planning and reporting of the AAR, and should compile the final AAR action plan.

• Lead facilitator or lead interviewer. This person leads the overall facilitation of a working group AAR, or plans the interview schedule for a key informant interview AAR. It is important that the lead facilitator or lead interviewer is impartial and was not involved directly in the response (for example, they could be an international expert, or a member of WHO regional or headquarters staff).

• Facilitators and interviewers. These people support the lead facilitator or lead interviewer, guiding the discussion around key themes, and preventing deviation beyond the planned scope and objectives. If necessary, a further role is to manage interpersonal conflicts by ensuring that discussions remain focused on underlying issues.

• Note takers. Note takers ensure that comments and discussions are captured and documented. All AAR formats require note takers. In a working group format, each pillar (working group) should have its own note taker. The note takers should have some familiarity with the topic and the country’s organizational structures, but will not necessarily be technical experts.

• Report writer. The writer consolidates inputs from note takers and interviewers to produce a final

AAR report for review by the overall AAR lead.

In some cases, one person can cover several roles. Annex 6 provides example terms of reference for each

AAR team member.

3.4 DEVELOP A BUDGET

Once the AAR format has been chosen and participants have been identified, it is important to build a budget for the AAR at an early stage, so that senior management can make the necessary funds available. Budget templates are included in the AAR toolkits.

3.5 DEVELOP A CHECKLIST AND AGENDA

Depending on the format selected, the preparation phase can be demanding in terms of time and resources. Checklists have been designed to help the AAR team prepare for the AAR. After choosing the most appropriate format for the AAR, it is recommended that the team prepares a draft agenda. Examples of draft agendas for the debrief and working group AARs are available in the AAR toolkits.

3.6 SUMMARIZE IN A CONCEPT NOTE

A concept note summarizes the key information agreed in the design phase. Developing a concept note will enable information to be shared with senior management in order to gain support for and commitment to the AAR and its follow-up. The concept note can also be shared with partners to encourage their participation and contribution. A concept note template is provided in the AAR toolkits.

3.7 INFORM STAKEHOLDERS (PARTICIPANTS) AND FACILITATORS

Once a concept note has been finalized, a message to initiate the AAR should be sent to participants and facilitators to introduce them to the format and objectives of the process and their roles in it. Examples of an email template to initiate an AAR can be found in the AAR toolkits.

3.8 VENUE

The AAR lead should ensure a venue is identified to host the AAR. Depending on the AAR format, the specifications for the venue will vary.

For the working group format, a room should be able to accommodate a world café session, plenaries,

and facilitated group discussions. There should be enough wall space for posting AAR results.

4. PREPARING FOR THE CONDUCT OF AN AARIn preparing for an AAR, a number of key actions should be carried out. The main steps that are common across all formats are outlined below. This preparation should be led by the AAR lead, in consultation with the lead facilitator.

4.1 COLLECT AND REVIEW RELEVANT BACKGROUND INFORMATION

For all AAR formats, facilitators and interviewers should have a sound understanding of the event under review. The AAR team should collect and review the background information necessary to gain a thorough understanding of the response actions that have been implemented. This will provide a common operating picture for discussion and for the preparation of facilitation tools. This background information can include the national emergency response plan, contingency plans, and the incident management structure.

It can also include documents that were developed during the response, such as:

• strategic response plans for the event;

• situational reports;

• operational reviews and response evaluations;

• outbreak reports;

• media reports.

For more details on the background information that can be collected, see Annex 7.

4.2 REFINE THE TRIGGER QUESTIONS

Trigger questions are used to guide discussions with a group or with individuals, and are organized according to the pillars being reviewed. Questions should be open because they are used primarily to generate discussion and to frame the scope of the analysis. They should be adapted to the context and expected outcomes for each function.

A series of trigger questions for an AAR should be based on the three phases described in section 2.4: objective observation; analysis of gaps/best practices and contributing factors; analysis of best practices and enabling factors and identification of areas for improvement.

To ensure a holistic review of any given pillar, trigger questions should address the following three thematic elements (where relevant to the event).

Coordination:

• coordination within the health sector – roles and responsibilities and coordination at administrative levels (local, regional and national);

• coordination across sectors – with partners and, where relevant, with the international community.

Resources:

• human resources capacity – availability of qualified and trained human resources;

• relevance of plans and procedures – clarity in roles and responsibilities and planned actions;

• financial and material resource requirements – availability of equipment, logistics and funds.

Technical aspects:

• specific technical aspects related to the pillar under review.

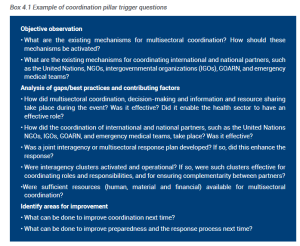

The development or adaptation of trigger questions should be led by the main facilitator and should be agreed with the AAR lead. Box 4.1 provides examples of questions for intersectoral and stakeholder coordination.

Box 4.1 Example of coordination pillar trigger questions

Objective observation

• What are the existing mechanisms for multisectoral coordination? How should these mechanisms be activated?

• What are the existing mechanisms for coordinating international and national partners, such as the United Nations, NGOs, intergovernmental organizations (IGOs), GOARN, and emergency medical teams?

Analysis of gaps/best practices and contributing factors

• How did multisectoral coordination, decision-making and information and resource sharing take place during the event? Was it effective? Did it enable the health sector to have an effective role?

• How did the coordination of international and national partners, such as the United Nations

NGOs, IGOs, GOARN, and emergency medical teams, take place? Was it effective?

• Was a joint interagency or multisectoral response plan developed? If so, did this enhance the response?

• Were interagency clusters activated and operational? If so, were such clusters effective for coordinating roles and responsibilities, and for ensuring complementarity between partners?

•Were sufficient resources (human, material and financial) available for multisectoral coordination?

Identify areas for improvement

• What can be done to improve coordination next time?

• What can be done to improve preparedness and the response process next time?

Annex 8 gives further examples of trigger questions for various pillars of a response to a public health event.

4.3 IDENTIFY AND BRIEF FACILITATORS AND INTERVIEWERS

The selection of the facilitators and interviewers is largely dependent on the objectives assigned to the AAR and the organizational culture in which the review is taking place. For key informant interview AARs, interviewers should not have been involved in the response, to ensure candid feedback and confidentiality. For debrief or working group AARs, the lead facilitator should be external to the response, whereas the working group facilitators can be drawn from both internal and external sources. Facilitators can come from within the health sector or elsewhere, including academia, humanitarian organizations or civil society.

Facilitators and interviewers should be briefed on their roles. It is important to select facilitators and interviewers who will remain impartial and not influence group or individual feedback. Using a senior manager as a facilitator is not recommended because it could make participants reluctant to make critical remarks; but the facilitator should have some authority among participants and should have the ability to drive critical discussion.

A facilitator or interviewer should have excellent interpersonal and communication skills, and be familiar with root cause analysis (see Box 5.1). The person should also have a sound knowledge of the technical areas being reviewed. In addition, a facilitator or interviewer should be fluent in the language used by participants; be able to listen more than speak; be able to clarify and summarize key points; and be able to guide participants through the discussions or the interviews.

4.4 SETTING UP AN AAR

For debrief or working group formats, several days before an AAR (ideally between two and five days before it starts), the AAR lead and the lead facilitator should hold a coordination meeting with the AAR team, including facilitators, note takers and other team members. Background material and guidance material (for example, facilitators’ manuals) should be distributed in advance of this preparatory meeting.

This meeting should familiarize the AAR team with the objectives, agenda, roles and responsibilities, and trigger questions selected for the AAR. One facilitator and one note taker should be assigned to each pillar. This pre-meeting is vital to ensure that working group facilitators are aware of and comfortable with their roles and what is expected of them.

For key informant interview AARs, the lead should hold a preliminary meeting with all interviewers. This meeting should introduce the scope and objectives of the review, as well as the interview approach, to ensure that there is consistency in the conduct of interviews and the capture of all information during the interviews.

5. DURING AN AARThe opening session of an AAR workshop following the debrief or working group formats aims to give participants a common operational and contextual picture of the event. It should include a brief overview of the IHR (2005), countries’ obligations under the IHR (for example, travel and trade measures), and the benefits of capacity-building and reporting. The lead facilitator should introduce the agenda, objectives, scope, methodology and expected outputs of the AAR.

The AAR toolkits contains generic PowerPoint presentations to support this stage.

For a key informant interview AAR, advance email communication from the AAR lead should introduce the scope, objectives and processes of the review. This communication should also be used to schedule or confirm interviews.

5.1 CONDUCT THE ANALYTICAL PART OF AN AAR

This part of an AAR, in which participants work to identify and agree on the challenges and best practices apparent during the response and develop measures to strengthen capacity in the future, is the most substantive part of an AAR.

The analysis should follow the principal logic of objective observation, gap analysis and identification of areas for improvement, using the trigger questions that were selected for the AAR. For the working group or debrief formats, facilitation should encourage interaction and active participation around the following areas or sessions.

5.1.1 Identification of capacities

The inventory of the capacities that existed prior to the event declaration, and which could have been used to support the response, should be established. The capacities are grouped in the following categories:

• plans and policies;

• resources;

• coordination mechanisms;

• preparedness activities (including prevention measures such as immunization);

• others.

5.1.2 Timeline of key milestones

The timeline – created by establishing a chronology of activities – is meant to develop a common understanding of what actually happened during the response. It should be as comprehensive as possible in order to establish whether actions were timely, appropriate and adequately resourced. At minimum, the following key timeline indicators should be highlighted and discussed:

• date of start of outbreak or event;

• date of detection of outbreak or event;

• date of notification of outbreak or event;

• date of verification of outbreak event;

• date of laboratory confirmation;

• date of outbreak or event intervention;

• date of public communication;

• date outbreak or event declared over;

• AAR timeline start (often the beginning of the response);

• AAR timeline end (often the end of the response).

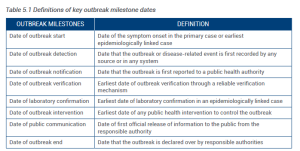

For disease outbreaks, the specific definitions given in Table 5.1 can help participants identify the key

milestone dates.

Table 5.1 Definitions of key outbreak milestone dates

Note: Definitions revised during the Salzburg Global Seminar, session 613: Finding outbreaks faster: how do we measure progress? (4–8 November 2018).

From these dates, at least four timeliness metrics, measured as the time interval between two relevant

outbreak milestones can be evaluated to assess the speed of the outbreak recognition and response:

• time interval to detection (between outbreak start and outbreak detection);

• time interval to laboratory confirmation (between outbreak detection and laboratory confirmation);

• time interval to public communication (between outbreak detection/laboratory confirmation

and public communication);

• time interval to response (between outbreak detection and outbreak intervention).

For disease-specific AARs, participants are required to interpret the timeline of activities against the

epi curve for the disease, and discuss the impacts of their interventions on outbreak control.

For AARs conducted for other public health events, thissession allows participants to provide an elaborate

list of all critical activities undertaken during the response, and discuss their impacts in the next session.

5.1.3 Identification of strengths and challenges, and new capacities developed

During this session, and while referring to the other sessions of an AAR, participants will identify all the

strengths and challenges identifiable in the response.

By the end of the AAR, regardless of the format, the same outputs are expected:

• clear articulation of best practices and their impacts on the response, and use of root cause

analysis (Box 5.1) to identify the factors that enabled the best practices (4);

• clear articulation of challenges faced during the response and their impacts, and use of root cause analysis to identify the limiting factors that contributed to the challenges;

• given the understanding of best practices and challenges, identification of clear actions required to embed the best practices, address the challenges, and strengthen preparedness for future responses;

• use of the actions described above to elaborate clear activities, responsible focal points, the resources needed, and timelines for implementation.

Box 5.1 Root cause analysis

Key informant interviews employ a similar set of questions and analytical techniques (for example, root cause analysis as shown in Box 5.1), although in an interview format this should be interwoven through one-on-one discussions. As much as possible, interviewers should use a similar set of questions when interviewing different people for the same response pillar, so that answers can be compared.

The AAR toolkits include facilitators’ manuals that provide detailed guidance on running AARs in the

debrief, working group and key informant interview formats.

For disease-specific AARs, the review of limiting and enabling factors for challenges and best practices identified during the response should take into consideration both the timeline and the standards for prevention and control peculiar to each disease. The facilitator or some group members for each pillar will be expected to have good knowledge and understanding of the event under review. All reference documentation, including the latest publications about the disease, should be provided to participants to enable informed discussions.

Also during this session, highlights of new capacities developed during the response will be presented for each pillar.

5.1.4 Evaluation of IHR (2005) core capacities performance during an AAR

Immediately after identifying the best practices and challenges of the response under review, participants may be invited to review the extent to which selected IHR core capacities were used during the response, using an objective-based evaluation with specific qualitative ratings(5). These ratings are as follows:

P = performed without challenges;

S = performed with some challenges; M = performed with major challenges; U = unable to be performed.

To guide participants, definitions of the different ratings are provided in Annex 9.

Table 5.2 presents IHR (2005) capacities and examples of evaluation tasks/objectives that can be

used to identify the extent to which selected capacities performed during the response.

Table 5.2 IHR (2005) core capacities performance evaluation form used during an AAR

Note: Participants may decide through consensus to add and review a capacity that is not listed in the table above.

5.2 BUILD CONSENSUS AMONG PARTICIPANTS

Building consensus consists of a final summary of best practices, challenges, new capacities developed and AAR indicators evaluated during the AAR discussions. In the debrief and working group AARs, this consensus can be achieved through plenary or group discussions. Such discussions should be held to validate results and create a sense of ownership to help ensure that corrective actions are taken. Before closing, a final working group session should be carried out to integrate any additions or comments from the debriefing session.

For AARs in the key informant interview format or the mixed-method format, draft findings should be shared with all those involved for feedback and validation. Ideally, findings should be validated during a group debrief session, although this may not be possible in all contexts.

5.3 CLOSE AN AAR AND CONDUCT AN AAR EVALUATION BY PARTICIPANTS

For AARs in the working group and debrief formats, an evaluation of the AAR workshop and its methodology should be conducted before closing in order to make any necessary improvements to the format or methodology used. The toolkits provide an AAR evaluation form template.

6. PRESENTING AAR RESULTS AND FOLLOW-UP ACTIONS

This chapter will provide guidance on how to conduct AAR debriefings, how to present the final report of an AAR, how to document the progress made following the implementation of recommendations from an AAR and how to capitalize on lessons learned.

6.1 CONDUCT AAR DEBRIEFINGS

6.1.1 AAR team debriefing

The purpose of the AAR team debriefing is to reflect on the overall planning, preparation and conduct of the AAR. The debriefing can also establish the roles, responsibilities and timelines for completion of the AAR reports and other deliverables. This should occur within one week of completing the AAR.

For AARs in the debrief and working group formats, this informal discussion is often led by the AAR lead or by the main facilitator, and aims to identify lessons and opportunities for similar future projects. For the key informant interview format, this can be done through a group teleconference or online meeting with all interviewers, led by the AAR lead.

The AAR team debriefing can be used to discuss how to improve the AAR process for the next event, considering that flexibility in the process of undertaking an AAR allows planners to adjust and find the best model for the culture and system being reviewed.

This is also an opportunity for the AAR team to discuss and finalize the executive summary to present to

the senior management.

6.1.2 Senior management debriefing

Senior management should be briefed on the outcomes of an AAR, including the best practices and

challenges identified, and the agreed follow-up actions.

The purpose of this debriefing is to gain support from the necessary authorities to mobilize the resources required to implement the identified actions. Having senior management endorsement of the outcomes also increases the likelihood and impact of learning at a wider institutional level, and contributes to a culture of continuous improvement and critical analysis through AARs. Senior management can also endorse the findings and give authorization for wider circulation of the results.

6.1.3 AAR as an opportunity for advocacy, resource mobilization and strategic partnership

To build on the momentum created by an AAR, other types of debriefing can be organized, such as advocacy and resource mobilization meetings, where key findings and ways forward are shared. The highest level of advocacy is encouraged, including participation of the most senior government officials and those from other ministries and sectors (such as the media, technical and financial partners, and embassies).

These debriefings will also help the ministry of health build strategic partnerships with stakeholders to

improve preparations for the next public health event and strengthen collaboration for future responses.

They also present opportunities for direct engagement of partners and donors to secure their commitment

to institutionalize and build longer-term capacities for prevention, detection and response.

6.2 AAR FINAL REPORT

The report writer should receive the notes from the note takers and begin to integrate them into a comprehensive final report. A generic report template is available in Annex 10 as well as in the AAR toolkits. It comprises the following key sections:

1. Executive summary;

2. Background on emergency under review;

3. Scope and objective of review;

4. Methods;

5. Findings;

6. Key activities;

7. Next steps;

8. Conclusions.

Most importantly, the report should include an action plan for following up actions identified during the

AAR.

WHO stands by to support the drafting and implementation of the report.

After initial drafting, the report writer should consult with the AAR lead and other facilitators and interviewers to ensure that all relevant discussions are accurately captured. The report should also be shared with AAR participants and interviewees for comment, and shared with senior management for formal validation before wider circulation.

The fundamental output of the AAR is an action plan for key activities and recommendations, with responsibilities and timelines assigned, and its implementation should be closely monitored. It should identify:

• activities (with costs, timelines and responsible authorities) for immediate action that can be taken to improve preparedness with few resources (“quick wins”);

• activities that require more resources or longer-term implementation, and which should be incorporated into other planning processes and budget cycles.

One example of a relevant planning process into which such activities can be incorporated is the national action plan for health security, a comprehensive, multisectoral and collaborative plan to increase preparedness for public health threats.

Activities will also be prioritized and categorized in terms of whether they are short-, medium- or long- term activities, based on the urgency with which they should be implemented to improve preparedness and response capacities. The highest priority will be given to activities that address imminent risks.

The AAR lead must ensure that activities are assigned to a specific person or authority (for accountability); and that activities are costed and sequenced; and can be monitored. Activities should be presented in a format conducive to planning and implementation (for example, a planning matrix or Gantt chart). A focal person should be selected to shepherd the AAR action plan and identify the human and financial resources required.

The plans for disseminating the final AAR report should be agreed during the AAR planning process. Sharing the findings can be helpful for other countries and contexts with similar challenges and risks. The decision on whether to publish the final AAR report resides with health authority’s senior management. In some situations, it may be advisable to prepare an additional report with sensitivities removed to be shared with a broader audience.

6.3 DOCUMENTING PROGRESS: POST-AAR FOLLOW-UP

While the Member State is the owner and custodian of the action plan and its activities, WHO can play a role in following up on its implementation, especially for action plans resulting from AARs conducted under the IHR Monitoring and Evaluation Framework.

Three months after an AAR (or earlier if required and agreed), and then regularly on a quarterly basis, WHO may provide assistance and work with the country health authorities to monitor the implementation of the AAR action plan and identify any challenges.

This will help also to monitor how the implementation of the AAR recommendations contributes to improvements in the overall preparedness and response capacities for health emergencies.

Documentation of progress will be based on evidence of the status and impact of the activities implemented, including any relevant changes in behaviour and the development of new capacities for preparedness and response to health emergencies.

Both qualitative and quantitative information may be collected through the review of relevant information sources, including concept notes, reports and media releases, and through interviews with and field visits to government officials and key stakeholders.

Equally, the post-AAR follow-up will be an opportunity to see and document how the implementation of the AAR action plan contributes to the improvement of voluntary external evaluation scores (if a voluntary external evaluation has been done in the country), or to the development of the IHR core capacities in general.

6.4 LESSONS LEARNED DATABASE

Countries should consider creating a repository of key challenges, best practices and recommendations resulting from AARs, which can be easily accessed at all times during the preparedness for and response to an emergency. Such a repository can help build institutional memory for lessons learned, and provides a resource for emergency preparedness and response stakeholders. The lessons learned database can be used by the country that experienced the outbreak or event whose response was reviewed through an AAR, and also by other countries that may be facing similar events or that are interested in strengthening their preparedness capacities by institutionalizing best practices and anticipating potential challenges should a similar event occur. The objective of the database is to facilitate and share learning between emergencies, and to apply findings to other contexts and events. Recording lessons in a central location also ensures that the same mistakes do not recur.

What is CASPER?[3]

CASPER is a type of Rapid Needs Assessment (RNA) that provides household-level information to public health leaders and emergency managers. The information generated can be used to initiate public health action, identify information gaps; facilitate disaster planning, response, and recovery activities; allocate resources, and assess new or changing needs in the community. It is a cross-sectional epidemiologic design; it is not surveillance.

The CASPER methodology is an adaptation of epidemiologic techniques used by scientists in the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) to estimate vaccine coverage in Africa.

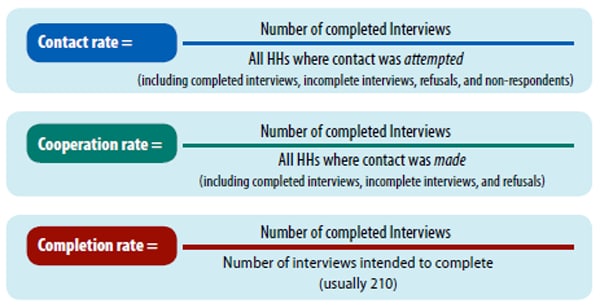

The cluster sampling design used for CASPER involves two-stages (30 clusters selected probability proportional to size and seven households interviewed within each cluster) and provides estimates for the population.

13.07 Module 13 Worksheet-CASPER – Link to Canvas Site

In this assignment you will review the materials that you did in your group assignments and answer the questions related to preparation for a CASPER assessment for the community.As a reminder here are the three scenarios from the exercise:

- You work for a local public health department in a county with a population of 450,000 persons. In your community there are several major manufacturing facilities and a public university. The university has a student body attendance of 22,000.

Your epidemiology section has received three reports of student from the campus that have been diagnosed by an attending physician with possible Neisseria meningitidis based upon their signs and symptoms. The physician has drawn spinal fluids for confirmation test and results are expected within 24 hours.

The three students are roommates in student housing that is on campus.

- The lab results have come in and they confirm that the three students do have Neisseria meningitidis.

You have contacted the three students, and this is what you have determined.

One works in the main cafeteria for the university that serves meals to all resident students and others that visit the campus including conferences held in the Student Union Building,

One is a freshman that is taking the general education courses with high enrollment in face-to-face classes. Classes included a Foundations 100 session with 100 students, a large enrollment General math and chemistry class plus a few others.

The last student is very active in Service Learning and volunteering with the refugee population in the community. This student also is somewhat involved in volunteering at a local homeless shelter.

Each of the students were going about their normal activity up to and just a little after signs and symptoms developed.

You have now completed your work on the outbreak it is time to do an After-Action Report. Part of the AAR will be to see how effective you were within your community related to the outbreak. The administration has determined that one of the tools that will be used to conduct a CASPER. In order to get ready for the CASPER your team needs to address the following questions contained in the CASPER document in the textbook that outlines preparing for a CASPER.

Please address the following questions with at least 2 to 3 sentences each.

- How is the CASPER information going to be used? Basically what will be the objectives of the CASPER?

- Who are the Stakeholders?

- When should the assessment be conducted?

- What is the population of interest? What is the area of interest (i.e., Sampling frame)?

- What resources and approvals will be needed?

- Who will identify the clusters for the first stage of sampling?

- Who will conduct the CASPER data analysis, write the report and disseminate the results? (Note: Consider looking at the ICS structure when developing this response}

How can CASPER be used?

There are many opportunities for CASPERs to influence public health. A CASPER can be used in both a disaster and non-disaster setting.

For example, CASPER methodology has been used to do the following:

- Assess public health perceptions

- Estimate needs of a community

- Assist in planning for emergency response

- As part of the public health accreditation process

Regardless of the setting and objectives, once the decision to conduct a CASPER has been made, it should be initiated as soon as possible. See the Interactive Map for examples of how CASPER has been used throughout the United States since 2001.

What is in the CASPER toolkit?

In the early 2000s, the two-stage cluster method became an increasingly widespread method for disaster response. Because of this, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) developed the CASPER Toolkit pdf icon[PDF – 17 MB] to outline and standardize the assessment methodology. As part of this process, CDC coined the term CASPER to distinguish it from, and avoid confusion with, other rapid needs assessments.

The CASPER toolkit provides guidelines to assist personnel from any federal, state, tribal, local, or territorial (STLT) public health departments or other emergency response agencies in conducting CASPER. It is intended to assist those in conducting a CASPER by providing a standardized, step-by-step guide and includes the following:

- Preparing checklist

- Questionnaire development

- Sample selection

- Training

- Data collection

- Analysis

- Report writing

- Templates and examples

Public health personnel, emergency management officials, academics, or others who wish to assess household-level public health needs will find the toolkit useful for rapid data collection for actionable decision making during disaster or non-emergency situations.

Why is this information important? What is the benefit of CASPER?

Information is key for decision-making. Information sent to the right people, at the right place, at the right time, is optimal for any successful response. CASPER addresses this by providing valid information rapidly about the general and health needs of a community to decision-makers. CASPER is generalizable (providing population estimates), timely, relatively low cost, reported in a simple format, and flexible.

While CASPER was originally designed to provide information during a disaster response, it can also be used when population-representative data are needed during other disaster phases (preparedness, recovery, mitigation) and in situations unrelated to a disaster. For example, public health departments have used CASPER to do the following:

- Identify household-level information about community health status

- Learn more about emerging infectious diseases such as Zika virus and H1N1

- Assess community awareness, opinions, and concerns on subjects such as opioid use, e-cigarettes, coal gasification plants, healthy homes, and radiation emergency preparedness

How are data used?

Data are used to provide situational awareness, confirm (or contradict) rumors or anecdotal reports, identify and provide estimates of needs in the community (e.g., food, water, medication), establish priorities, and tailor interventions and communication messaging. Other potential benefits include the following:

- Monitor changes in community needs

- Raise visibility of emergency management and public health in the community

- Justify requests for outside assistance or funding

- Evaluate the effectiveness of response activities

- Serve as field exercise to build capacity and prepare the workforce for emergency situations

CASPER data has been impactful in the past from resource allocation and support for funding of projects or services to targeting messages and future planning. To learn more about previous CASPERs, view the Interactive Map of CASPERs.

What are some considerations prior to conducting a CASPER?

Prior to conducting a CASPER, you should decide if CASPER provides an appropriate sampling methodology based on your objectives, time frame, and available resources. CASPER uses a two-stage cluster sampling design in which 30 clusters are selected proportional to the number of households in the cluster and then 7 households are selected systematically for interviews for in each of the 30 clusters. A clear understanding of how CASPER information will be used, who the relevant stakeholders are, and needed and available resources is important prior to moving forward with your CASPER. Remember, a CASPER will be descriptive of the entire sampling frame (geographic area from which your sample is drawn); it will not provide detailed information on subpopulations or target specific groups. For example, if your objective is to determine the needs or status of pregnant women or persons experiencing homelessness, you should not conduct a CASPER.

How do I get started?

Contact CASPER@cdc.gov if you are interested in conducting a CASPER. CDC provides scientific consultation, technical assistance, and disaster epidemiology training to the following organizations:

- State, regional, tribal, local, territorial, or foreign health departments

- Federal agencies

- Non-governmental organizations

- Professional interest groups

- International organizations

- Academic institutions

- Foreign governments

To learn more about requesting assistance or training, please visit the Disaster Epidemiology and Response Team’s Training and Technical Assistance webpage. Additionally, if you would like more information, you can check out the CASPER eLearning for an overview of the CASPER methodology, its uses, and the local capabilities required to conduct a CASPER.

CASPER Phases

There are four phases in a CASPER: prepare for the CASPER, conduct the CASPER in the field, analyze the data, and write the report.

Phase 1: Prepare for CASPER

As you prepare to conduct a CASPER, there are many planning questions that should be addressed. Work with leadership, key stakeholders, and CASPER subject matter experts (SMEs) within your state or CDC to help plan and prepare. Keep in mind that preparing for a CASPER can take several hours (e.g., during a response) or, if time allows, several months (e.g., in a non-disaster setting).

How to Prepare for CASPER.

Know the Purpose

How is the CASPER information going to be used?

Understanding how the information is going to be used will help create a clear vision and narrow the scope of information collected. Having clear objectives is imperative to ensuring that the appropriate data are collected to generate useful information for public health action.

Who are your stakeholders?

Stakeholders will help inform the objectives of the CASPER. Identifying who (e.g., emergency management, state and local health partners) will use the CASPER data is integral to both the development of the questionnaire and planning and implementation of action items based on the results.

When should the assessment be conducted?

A CASPER can be conducted any time that the public health needs of a community, and the magnitude of those needs, are not well known, whether during a disaster response or within a non-emergency setting. During a response, factors such as safety of the interview teams in the impacted area, population displacement, changing community needs, and available resources may affect the timing of the CASPER. Therefore, the objectives of the CASPER and timing of the CASPER are closely linked and should complement each other. Typically, a CASPER conducted with approximately 15 teams can be completed within two midweek (e.g., Tuesday-Thursday) afternoons (e.g., 2pm-7pm). Fewer teams, other days, or earlier hours will likely increase the needed hours of data collection. Weekends and morning hours have shown to be less effective and may increase frustration among teams. Contact CDC for guidance and suggestions on scheduling your CASPER fieldwork.

Know Your Setting

What is the population of interest? What is the area of interest (i.e., sampling frame)?

It is important to decide what area of the territory, state, county, or city you want the results to reflect when determining the sampling frame (i.e., area in which the sample is drawn). If relevant, obtain information from other assessments conducted (e.g., flyovers and area damage assessments, state or national surveys) because such information can be beneficial in determining your objectives and assessment area(s). Remember that CASPER results are descriptive of the entire sampling frame provided there is at least an 80% completion rate. Keep this in mind when determining your sampling frame as it will affect the interpretation of your data.

By when are the data needed?

Keep in mind your deadlines. A CASPER can be conducted in as short as 1-2 days in the field with results produced within 36 hours of completion of field data collection.

Know Your Resources

What resources and approvals are needed?

Identify the resources and approvals necessary including interview team members (including transportation), headquarters location, any funding needed and corresponding paperwork, Institutional Review Board (IRB) paperwork, supplies, and more. CASPER data can be collected via paper forms or electronic devices; know what is available and the advantages and disadvantages of each.

Institutional Review Board (IRB) and CASPER

Be sure to follow your local IRB guidance for all CASPER-related activities and materials. CASPER typically does not require full IRB review; however, have your local IRB review the proposed activities in advance for confirmation. Many times, especially during a response, you will complete a determination form to exempt the CASPER from the full IRB process. This is because CASPERs tend to be classified as public health non-research or public health practice and are not considered research.

Who will identify the clusters for the first stage of sampling?

CASPER is a two-stage cluster sampling methodology. In the first stage, clusters (traditionally 30) are selected with a probability proportional to the estimated number of households within the clusters. Identify someone who can select the sample appropriately. CDC SMEs are available for sampling and mapping assistance. Learn more about CASPER’s Sampling Methodology.

Who will conduct the CASPER data analysis, write the report, and disseminate the results?

After field data collection, data will need to be entered, cleaned, and analyzed. Once analysis is complete, it is important to disseminate the results for prompt action. The local lead of the CASPER is often the lead of this effort and helps coordinate the team members and actions involved throughout all phases of the CASPER, however, CDC SMEs are available for assistance.

Phase 2: Conduct the CASPER in the Field