8. Group Communication and Social Networks

Overview

Whether it’s a study group, a project team, or an online community, much of our communication happens in groups. In this chapter, we’ll explore how communication shapes and is shaped by small groups, teams, and social networks. (MLO1, MLO2)

We’ll start by examining roles and dynamics in small groups and teams. From leaders and note-takers to quiet participants and conflict mediators, everyone contributes to how groups function. You’ll learn how communication builds trust, resolves conflict, and supports collaboration. (MLO1)

Next, we’ll look at how social networks, both online and offline, influence communication patterns. These networks affect who we talk to, how often, and what kind of information we share. Understanding them reveals how relationships, status, and influence flow through different communities. (MLO2)

Finally, we’ll explore digital relationships—those formed and maintained through social media, messaging apps, and online platforms. We’ll consider how these differ from face-to-face connections and how they impact friendships, family ties, and professional collaboration. (MLO3)

By the end of this chapter, you’ll be able to examine communication roles in small groups (MLO1), analyze how social networks shape communication (MLO2), and evaluate how digital relationships influence social interaction (MLO3).

Module Learning Outcomes

By the end of this chapter, students will have had the opportunity to:

- Examine communication roles and dynamics in small groups and teams. (MLO1)

- Analyze how social networks influence communication patterns and behavior. (MLO2)

- Evaluate the impact of digital relationships on social interaction. (MLO3)

These Module Learning Outcomes align with CLOs 1, 2, and 4 and ULOs 1, 3, and 6. See the Introduction for more details.

Communication in Groups, Teams, and Networks

Group communication is different from one-on-one interactions. Whether you’re in a study group, workplace team, or volunteer committee, the way we collaborate shapes both outcomes and relationships.

We often focus on dyadic communication—interactions between two people—but working in groups requires different skills to navigate multiple perspectives, roles, and relationships. Small groups involve three or more people working toward a common goal, influencing one another, and developing a shared identity. This section explores what makes group communication unique, including size, structure, roles, interdependence, and group types.

Size of Small Groups

Small groups typically have at least three members, but there’s no strict upper limit. As groups grow beyond 15–20 members, close interaction becomes harder to maintain. For example, a six-person group has 15 potential one-on-one connections; a 12-person group has 66. That’s a big jump in complexity (Hargie, 2011). Larger groups risk overwhelming members or making participation feel impersonal, so smaller sizes are often better for collaboration.

Structure of Small Groups

A group’s structure is shaped by internal factors, like members’ skills, motivation, and leadership tendencies, and external factors, such as size, task, and available resources (Ellis & Fisher, 1994). For instance, a student book club might set its own rules, while a state commission may follow formal procedures.

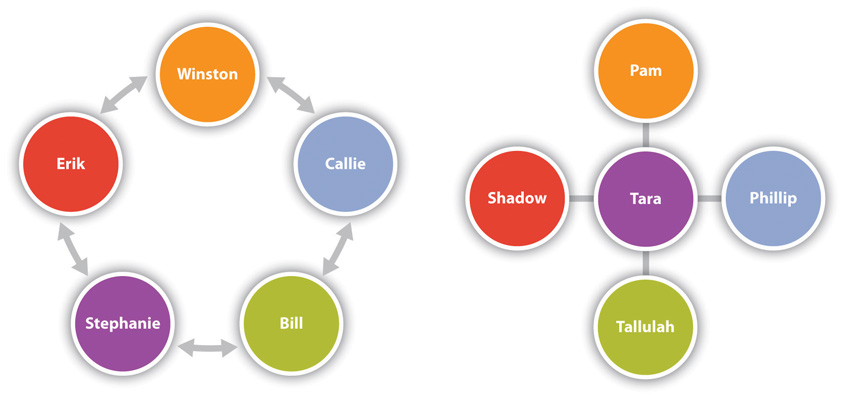

Group structures affect communication flow and decision-making. Some groups follow a circle pattern, where each person is connected to two others. Others use a wheel, where a central member connects everyone else. Research shows centralized structures like the wheel are faster at making decisions, while decentralized ones like the circle are better at solving complex problems.

In a circle, members share information in a loop. Coordination is easier when communication only needs to pass between a few people. In a wheel, a central figure facilitates all interaction—helpful for task delegation or time-sensitive work, but potentially overwhelming for that person.

These patterns influence power. Centralized structures often position one person as a leader or gatekeeper. Decentralized structures support collaboration and equal access to information but may slow decision-making.

For example, the “Circle” group structure in Figure 8.1 shows that each group member is connected to two other members, one on each side. This can make coordination easy when only one or two people need to be brought in for a decision. In this case, Erik and Callie are very reachable by Winston (because they are on either side of Winston in the circle), who could easily coordinate with them. However, if Winston needed to coordinate with Bill (on the other side of Callie) or Stephanie (on the other side of Erik), he would have to wait for Erik or Callie to reach that person, which could create delays. The circle can be a good structure for groups who are passing along a task, and in which each member is expected to progressively build on the others’ work. A group of scholars co-authoring a research paper may work in such a manner, with each person adding to the paper and then passing it on to the next person in the circle. In this case, they can ask the previous person questions and write with the next person’s area of expertise in mind. The “Wheel” group structure in Figure 8.1 shows an alternative organization pattern. In this structure, Tara is very reachable by all members of the group because she is at the center of the wheel. This can be a useful structure when Tara is the person with the most expertise in the task or the leader who needs to review and approve work at each step before it is passed along to other group members. But Phillip and Shadow (found on opposite sides of Tara), for example, wouldn’t likely work together without Tara being involved.

Looking at the group structures, we can make some assumptions about the communication that takes place in them. The wheel is an example of a centralized structure, while the circle is decentralized. Research has shown that centralized groups are better than decentralized groups in terms of speed and efficiency (Ellis & Fisher, 1994). However, decentralized groups are more effective at solving complex problems. In centralized groups like the wheel, the person with the most connections, like Tara, is also more likely to be the leader of the group or at least have more status among group members, largely because that person has a broad perspective of what’s going on in the group. The most central person can also act as a gatekeeper. Since this person has access to the most information, which is usually a sign of leadership or status, he or she could consciously decide to limit the flow of information. However, in complex tasks, that person could become overwhelmed by the burden of processing and sharing information with all the other group members. The circle structure is more likely to emerge in groups where collaboration is the goal and a specific task and course of action aren’t required under time constraints. While the person who initiated the group or has the most expertise regarding the task may emerge as a leader in a decentralized group, equal access to information lessens such a rigid structure and the potential for a gatekeeping presence in the more centralized groups.

Interdependence

In small groups, members rely on each other to achieve shared goals. This interdependence can be a strength—diverse perspectives and skills improve outcomes. But it can also lead to frustration if someone misses meetings or doesn’t follow through. Group success (or failure) is shared, which is why group work can be both rewarding and challenging.

Shared Identity

Groups often build identity through shared goals, values, and experiences. Some use symbols—like names, logos, or traditions—to strengthen that identity. A family reunion might involve matching shirts; a student club might adopt a motto. These practices foster belonging, but not all members feel equally included. Group identity influences trust, motivation, and performance.

Types of Small Groups

Small groups usually fall into two categories (Hargie, 2011):

- Task-oriented groups focus on specific goals, like drafting a policy or planning an event.

- Relational-oriented groups center on connection and support, like friend circles or support groups.

Most groups mix both purposes. Understanding their primary focus helps clarify how they operate.

Teams

Teams are a specialized type of group with shared goals, strong collaboration, and a focus on performance. According to Adler & Elmhorst (2005), effective teams typically have:

- Clear, inspiring goals

- A results-driven structure

- Competent, motivated members

- A collaborative climate

- High performance standards

- External support and recognition

- Ethical, accountable leadership

Virtual Groups and Digital Communication

Today, many groups work partially or entirely online. Whether it’s a remote project team, an online class, or a global collaboration, virtual groups use digital tools like video calls, messaging apps, and shared documents to stay connected (Ahuja & Galvin, 2003). These technologies shape not only how we work but also how we form and maintain relationships in digital spaces.

Virtual Groups

Virtual groups offer flexibility and access to diverse perspectives. They allow people from different time zones, locations, and backgrounds to work together. But they also face challenges. Without face-to-face interaction, it’s harder to read nonverbal cues like tone or facial expressions. Misunderstandings can arise from vague messages or unclear expectations. Technical difficulties—like poor internet or conflicting time zones—can also disrupt progress and morale.

To succeed, virtual teams must be intentional and clear in their communication. Effective strategies include:

- Using shared tools like collaborative documents, project trackers, or discussion boards to stay organized.

- Clarifying expectations by writing out roles, responsibilities, and deadlines.

- Checking in regularly to maintain trust, offer feedback, and build a connection.

- Acknowledging relational dynamics by being mindful of tone, inclusion, and emotional cues, even in texts or emails.

- Staying flexible and patient when navigating tech issues or time constraints.

Online communication requires balancing task-focused goals (getting the work done) with relational connection (building trust and support). Teams that invest in both tend to communicate better, stay engaged, and produce stronger results.

Digital Relationships

Digital relationships are connections formed and maintained through online platforms such as social media, messaging apps, forums, or collaborative tools. Unlike face-to-face interactions, digital relationships often rely on text, emojis, and asynchronous communication, which can lead to both clarity and confusion. These relationships allow people to stay connected across time zones and geographies, but they can also feel less personal or harder to maintain without regular engagement. In group settings, digital relationships require intentional effort to build trust, express tone, and maintain accountability, especially when nonverbal cues are limited or delayed.

Virtual vs. Digital Groups

You might wonder—is there a difference between virtual groups and digital groups? While the terms are sometimes used interchangeably, they’re not exactly the same.

Virtual groups are typically small teams or workgroups that meet online to accomplish a shared goal, such as a remote project team, a student committee, or an online class group. The focus is on collaboration, coordination, and productivity using tools like Zoom, Google Docs, or Slack.

Digital groups, on the other hand, are broader and often more informal. These include social media groups, online forums, and discussion boards where people connect around shared interests or identities. Digital groups may not have a specific task or deadline; they exist primarily within a digital space, not necessarily to complete a shared goal.

Key differences:

-

Virtual groups emphasize collaboration and task completion.

-

Digital groups emphasize social interaction or shared identity in an online space.

Understanding this distinction helps clarify how communication norms shift depending on the group’s purpose, structure, and platform.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Small Groups

Working in a small group can be both rewarding and challenging. On one hand, groups can achieve more together than individuals can alone. On the other hand, group work can be slow, frustrating, or unproductive without coordination and trust.

Advantages:

- Shared decision-making allows members to contribute ideas and perspectives.

- Diverse viewpoints can lead to more creative and well-rounded solutions.

- Synergy enables groups to accomplish more collectively than they could individually.

- Social connection expands networks and fosters support.

Disadvantages:

- Slower decision-making due to the need for discussion and consensus.

- Social loafing may occur when individuals contribute less effort (Karau & Williams, 1993).

- Coordination challenges, such as scheduling conflicts and uneven participation.

- Interpersonal conflict can derail progress if not managed constructively.

While small groups offer valuable opportunities for collaboration, their success depends on strong communication, mutual respect, and shared responsibility.

Small Group Development

Small groups change over time. As members join or leave, goals shift, or relationships evolve, the group moves through different stages. Psychologists Bruce Tuckman and Mary Ann Jensen (1977) identified five key stages of group development: forming, storming, norming, performing, and adjourning. These stages often overlap, repeat, or unfold out of order—but they help us understand how groups evolve.

Forming

In the forming stage, members reduce uncertainty by learning about the task and one another. They begin to define roles, goals, and basic norms. Cohesion starts to build (Hargie 2011), especially in voluntary groups, which often begin with optimism. In assigned groups, motivation may vary, but effective collaboration is still possible with shared commitment.

Storming

Storming involves conflict as roles, norms, and leadership begin to solidify. Disagreements about purpose, structure, or interpersonal dynamics may emerge. This tension can feel uncomfortable, but it’s a necessary step toward growth. Healthy conflict leads to stronger goals and clearer expectations—if managed productively.

Norming

In the norming stage, the group finds its rhythm. Norms—shared expectations about behavior—become clearer, often based on broader social cues (Ellis & Fisher, 1994). While some norms are helpful, others may limit participation or creativity. Challenging unhelpful norms can lead to growth, even if it means revisiting earlier stages.

Performing

During performing, the group collaborates efficiently. Members trust one another, build on each other’s strengths, and achieve synergy—the idea that the group achieves more together than individuals could alone. Social connections outside of meetings can strengthen this stage. But disruptions like role changes or conflict may require the group to adjust and regroup.

Adjourning

Adjourning occurs when the group disbands, whether by completing a task, losing members, or facing burnout. For cohesive groups, this can feel bittersweet. For less functional ones, it may be a relief. Reflection is key: acknowledging what worked (and what didn’t) helps members carry those lessons into future group experiences.

Interactive Group Development Model

Explore the five stages of group development below. While every group is unique, understanding these patterns can help you anticipate challenges, support group cohesion, and reflect on how your own group experiences unfold.

Small Group Dynamics

Group dynamics shape how members interact, influence one another, and make decisions. These patterns affect how people feel about the group, how well tasks get done, and how conflicts are handled. In this section, we’ll explore key aspects of group dynamics: cohesion, climate, socialization, conformity, and conflict.

Group Cohesion and Climate

Cohesion refers to the sense of belonging and commitment that group members feel. Climate is the emotional tone or atmosphere—whether the group feels supportive, respectful, and inclusive.

Positive group climates often share:

- Participation: Everyone has a voice and feels included.

- Supportive messages: Clear, respectful communication keeps relationships strong and tasks on track.

- Constructive feedback: Encouraging improvement without attacking individuals.

- Fairness: Turn-taking and equitable treatment build trust.

- Clear roles: Knowing who is responsible for what helps coordination.

- Motivation: Members stay engaged when their work feels meaningful.

Working in Teams

While group projects may feel frustrating in college, teamwork is a core part of professional life. Inspired by Japan’s success with team-based approaches, U.S. corporations have embraced teams as a way to increase efficiency, spark innovation, and reduce hierarchy (Jain et al., 2008).

Teams work best when:

- They are small enough to self-manage, but big enough for synergy—the creative energy that comes from combining diverse skills.

- They have a clear mission, a leader who assigns tasks based on expertise, and a culture of shared leadership (Daniel & Davis, 2009).

- They balance task focus with social connection—even high-pressure, high-stakes teams need trust and relationships to succeed (Solansky, 2011).

Challenges include:

- Lack of a shared history (since teams often form quickly for a specific project).

- High expectations with limited resources.

- Uncertainty and conflict from the absence of a traditional hierarchy (du Chatenier et al., 2010).

To overcome these challenges, effective team members:

- Think positively but realistically.

- Trust their teammates’ expertise.

- Stay reliable and approachable.

- Take initiative, ask critical questions, and give constructive feedback.

Socializing Group Members

Group socialization is the process of learning a group’s rules, norms, and expectations. Just like we’re socialized into cultural norms, we’re also socialized into group cultures (Ahuja & Galvin, 2003). This process helps members build a shared identity and understand how to function effectively within the group.

Groups with strong cohesion tend to socialize new members more successfully—when people feel connected, they’re more likely to “buy in.” The need for socialization also changes over time. Stable groups may not need much, but when new members join or the group forms for the first time, socialization becomes essential.

Group knowledge tends to fall into two broad categories:

- Technical knowledge includes the formal skills, processes, or tools the group uses (e.g., how to use a shared drive or project management app).

- Social knowledge includes the unspoken rules about tone, timing, and behavior (e.g., knowing when it’s okay to interrupt or joke around).

While technical knowledge is often taught through orientations or written guides, social knowledge is usually picked up informally—by observing others, asking questions, or making mistakes. Both types are essential for creating a group environment where people feel secure, informed, and ready to contribute.

Group Pressures

Groups create pressure—both subtle and overt—for members to follow shared norms. Without some pressure to conform, group identity wouldn’t stick, and coordination would fall apart. But too much pressure can silence important perspectives or cause harm.

Conformity

Some people naturally go along with group norms; others push back. Internal pressures like the desire for approval often lead people to self-monitor. We might feel guilty or embarrassed when we break group expectations, even if no one says anything. This self-discipline helps the group function without constant oversight (Ellis & Fisher, 1994).

External pressures also matter. If group success leads to rewards, or failure to consequences, members are more likely to conform. This can keep things running smoothly, but it can also discourage healthy disagreement.

While conformity can strengthen cohesion, it can also go too far. At its worst, it becomes groupthink.

Groupthink

Groupthink happens when the desire for harmony overrides critical thinking. It’s a pattern where members avoid conflict, silence dissent, and rush to agreement—even if the decision is flawed (Janis, 1972; Ellis & Fisher, 1994).

Warning signs include:

- Quick agreement without debate.

- Reluctance to question leaders or dominant voices.

- Suppression of alternative ideas or concerns.

Groups vulnerable to groupthink often:

- Have high cohesion.

- Face pressure to make quick decisions.

- Lack diverse viewpoints or open communication.

To avoid groupthink (Ellis & Fisher, 1994):

- Share leadership and rotate decision-making roles.

- Encourage dissent and welcome constructive criticism.

- Use anonymous idea submissions to reduce bias.

- Pause before finalizing decisions to reflect and revisit alternatives.

Challenging group norms respectfully and allowing space for disagreement can lead to better outcomes and stronger teams.

Group Conflict

Conflict is a natural part of group life, and not all conflict is bad. In fact, healthy conflict can spark creativity, deepen understanding, and strengthen cohesion.

Procedural conflict arises from disagreements about how the group operates, such as meeting times, decision-making methods, or task division. Leaders can resolve these issues by clarifying expectations, suggesting a vote, or streamlining the process. Addressed early, procedural conflict can help groups function more smoothly.

Substantive conflict focuses on what the group should do—its goals, priorities, or ideas. While it can feel tense, it often leads to better decisions by encouraging diverse perspectives and critical thinking. Mismanaged, however, it can lead to frustration or stalemates.

Interpersonal conflict is about who, not what. It stems from clashing personalities, communication styles, or values. It’s the most emotionally charged and the hardest to resolve. Unaddressed tension can damage trust and derail group work.

Managing Conflict

Groups can’t avoid conflict, but they can learn to manage it productively. Effective conflict management helps clarify issues, strengthen relationships, and keep group goals on track (Ellis & Fisher, 1994).

Strategies include:

- Clarify the issue: Make sure everyone understands the problem before jumping to solutions.

- Listen actively: Show respect by listening without interrupting or judging.

- Focus on needs: Get to the root of concerns, not just surface-level disagreements.

- Stay task-oriented: Keep the conversation on goals, not personal differences.

- Use inclusive language: “We” language builds unity; “I” statements reduce defensiveness.

- Set boundaries: Agree on guidelines to prevent interruptions, tangents, or personal attacks.

Well-managed conflict can lead to creative solutions, better decisions, and stronger group cohesion. Avoiding it may feel easier, but addressing it directly is what builds resilient teams.

Leadership and Small Group Communication

Leadership in small groups isn’t just about having a title—it’s about behaviors that guide, influence, and support group goals (Hargie, 2011). A person can hold an official role without demonstrating effective leadership, while others lead informally through action and communication.

Although leadership is often linked to traits like assertiveness, typically viewed as masculine, research shows effectiveness depends more on group expectations than gender identity (Haslett & Ruebush, 1999).

How Leaders Emerge

People become leaders in different ways:

- Designated Leaders are officially appointed or elected. Their success depends on group acceptance and skill.

- Emergent Leaders gain influence through engagement and competence, often stepping up when needed.

Three perspectives explain leadership emergence:

- Trait Approach: Leaders often stand out due to appearance, fluency, intelligence, and personality (Cragan & Wright, 1991; Pavitt, 1999).

- Situational Approach: Context matters. Some members are quickly ruled out, while others compete subtly to lead (Bormann & Bormann, 1988).

- Functional Approach: Leadership is what people do, not who they are. Facilitating discussion, solving problems, and motivating others are key behaviors anyone can learn (Cragan & Wright, 1991).

Leadership Styles

Effective leaders adapt their style to the group’s needs (Wood, 1977). Two useful models include:

Classic Styles (Lewin, Lippitt, & White, 1939):

- Autocratic: Makes decisions independently.

- Democratic: Encourages group input.

- Laissez-faire: Offers minimal guidance.

Communication-Based Styles (House & Mitchell, 1974):

- Directive: Sets structure and expectations—useful in new or high-stakes groups.

- Participative: Invites collaboration, aligning personal and group goals.

- Supportive: Prioritizes well-being and feedback, especially in relational groups.

- Achievement-Oriented: Sets high standards and motivates performance through challenge and vision.

Real-World Example: Steve Jobs as an Achievement-Oriented Leader

Steve Jobs, co-founder and former CEO of Apple, was known for his bold vision, relentless drive, and uncompromising standards. Rather than relying on focus groups or market research, Jobs trusted his instincts, challenging his team to think beyond conventional boundaries. Under his leadership, Apple launched iconic products like the iPod, iPhone, and MacBook, reshaping the tech industry.

This moment reveals how leadership communication influences group dynamics and performance:

- Jobs communicated a clear, ambitious vision that inspired team members to innovate and excel.

- His style was highly directive and achievement-focused, often disregarding traditional input in favor of creativity and bold risk-taking.

- While Jobs fostered a culture of excellence and innovation, his high expectations and intense approach also led to reports of workplace stress and burnout.

This example shows:

- Leadership communication can be a powerful tool for motivating teams and driving innovation.

- Achievement-oriented leaders may elevate group performance, but can also create tension if expectations overwhelm support structures.

- Effective leadership requires balancing vision with empathy, especially when navigating high-pressure environments.

Reflection Prompt:

Think of a leader you’ve worked with or observed either in a classroom, workplace, or community setting. What was their communication style like? Did it motivate, challenge, or discourage others? How did it affect the group’s dynamic and success?

Problem Solving and Decision Making in Groups

Group problem solving can be messy, but a clear, step-by-step approach helps teams stay focused, collaborative, and productive. This section introduces a common problem-solving model, decision-making methods, and how group dynamics, like personality, power, and diversity, shape outcomes.

The Group Problem-Solving Process

Many group models build on John Dewey’s reflective thinking process (Bormann & Bormann, 1988). A structured approach helps teams stay on track, especially when members lack shared history. Flexibility, not rigidity, keeps engagement high.

Step 1: Define the Problem

Identify the current issue, the desired goal, and the obstacles in the way (Adams & Galanes, 2009). Share information without jumping to solutions. Example: “Our state has no mechanism for reporting suspected ethical violations by city officials.”

Step 2: Analyze the Problem

Dig into causes and context. What hasn’t worked? What can we learn from other examples? Then, frame a guiding question. Example: “How can citizens report violations, and how will those reports be processed?”

Step 3: Generate Possible Solutions

Brainstorm freely without judgment. For complex issues, tackle each part separately. Example: How will reports be submitted? Who will review them?

Step 4: Evaluate Solutions

Assess options for credibility, feasibility, and impact. Don’t rush—revisit earlier steps if needed.

Step 5: Implement and Assess the Solution

Assign tasks, set deadlines, and plan how success will be measured. If the solution fails, decide whether to revise or regroup.

Interactive Group Problem-Solving Process

Explore the five-step process below to see how each stage works in real-world situations.

Following a structured process helps groups stay aligned and productive. While the exact steps may shift depending on the situation, this model offers a flexible guide for navigating challenges, avoiding confusion, and making thoughtful group decisions.

Problem Solving and Group Presentations

Presenting as a group brings challenges: dividing tasks, coordinating schedules, and aligning on content and design. Best practices include:

- Setting clear expectations and shared goals early

- Assigning roles (e.g., content lead, visual designer, coordinator)

- Rehearsing transitions and visual aids

- Creating a simple group contract

A strong presentation reflects collaboration, not just individual effort.

Decision-Making Techniques

Groups can make decisions in different ways, depending on how much agreement they seek. Common methods include:

| Decision-Making Technique | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Majority Rule | Quick, fair vote |

May alienate minority; can miss creative solutions |

| Minority rule by Expert |

Fast, high-quality decisions |

Depends on the expert’s credibility; the group may feel excluded |

| Minority rule by authority |

Efficient, respected leaders |

Can feel undemocratic; risk of bias or abuse of power |

| Consensus |

High-quality decisions; strong group buy-in and commitment |

Time-consuming; may lead to compromised solutions |

What Influences Groups

Personalities, roles, and social identities all shape how groups make decisions. Members may lean toward:

- Dominant or Submissive: (Taking charge vs. stepping back).

- Friendly or Unfriendly: (Collaborative vs. competitive).

- Instrumental or Emotional: (Task-focused vs. relational and expressive) (Cragan & Wright, 1999).

Diversity across gender, culture, and background also affects outcomes. Diverse groups often produce better decisions (Haslett & Ruebush, 1999), but only when inclusive communication practices are in place.

To support inclusive decision-making:

- Recognize socialized assumptions and stereotypes

- Create norms that encourage all voices

- Foster trust through respect and active listening

Discussion

As we’ve explored in this chapter, communication in groups is shaped by many factors: leadership styles, group norms, diversity, and the ways we collaborate to solve problems or make decisions. Whether we’re working on a class project, planning a community event, or contributing to an online group, the roles we play and the way we communicate affect the group’s success and our relationships with others. Group communication isn’t just about tasks; it’s about who speaks up, who stays quiet, and how power and privilege shape the conversation.

Let’s take a moment to reflect on how these ideas connect to your own life and experiences.

Communication in Groups and Teams

Discussion Prompt:

Think of a time when you participated in a group or team—this could be a class project, a workplace team, a volunteer committee, or an online group. What role did you play? Were you a leader, a note-taker, a quiet observer, or something else? How did communication shape the group’s success (or challenges)?

Consider:

- How were decisions made in the group?

- Was everyone able to contribute ideas, or did some voices dominate?

- Did conflict arise, and if so, how was it handled?

Follow-up Question:

How did differences in identity, power, or privilege shape the communication in the group? For example, did someone’s background, expertise, or confidence give them more influence? Were certain voices overlooked or dismissed? Looking back, how might you approach a similar group situation differently to create a more inclusive and effective communication environment?

Conclusion and Key Takeaways

Group communication is about more than sharing information—it’s how we collaborate, solve problems, and create shared meaning. In this chapter, we explored the roles, dynamics, and leadership styles that shape small group interaction, as well as how digital and social networks influence participation and belonging. Understanding how communication works in groups helps us navigate teamwork more effectively and build inclusive communities.

Key Takeaways

- Small group communication involves roles, norms, and leadership that influence decision-making and participation. (MLO1)

- Social networks shape who we connect with and how messages are shared, both online and offline. (MLO2)

- Virtual groups require intentional communication strategies to manage challenges and promote clarity. (MLO2)

- Inclusive group communication fosters creativity, trust, and equitable decision-making. (MLO3)

- Successful group members practice adaptability, self-awareness, and respect for diverse perspectives. (MLO1, MLO2, MLO3)

Check Your Understanding

References

Adams, K., & Galanes, G. G. (2009). Communicating in Groups: Applications and Skills (7th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Adler, R. B., & Elmhorst, J. M. (2005). Communicating at Work: Principles and Practices for Businesses and the Professions (8th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Ahuja, M. K., & Galvin, J. E. (2003). Socialization in Virtual Groups. Journal of Management, 29(2), 163.

Bormann, E. G., & Bormann, N. C. (1988). Effective Small Group Communication (4th ed.). Burgess.

Cragan, J. F., & Wright, D. W. (1991). Communication in Small Group Discussions: An Integrated Approach (3rd ed.). West Publishing.

Daniel, L. J., & Davis, C. R. (2009). What Makes High-Performance Teams Excel? Research Technology Management, 52(4), 40-41.

du Chatenier, E., Verstegen, J. A. A. M., Biemans, H. J. A., Mulder, M., & Omta, O. S. W. F. (2010). Identification of Competencies in Open Innovation Teams. Research and Development Management 40(3), 271.

Ellis, D. G., & Fisher, B. A. (1994). Small Group Decision Making: Communication and the Group Process (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Hargie, O. (2011). Skilled Interpersonal Interaction: Research, Theory, and Practice (5th ed.). Routledge.

Haslett, B. B., & Ruebush, J. (1999). What Differences Do Individual Differences in Groups Make?: The Effects of Individuals, Culture, and Group Composition. In Frey, L. R. (Ed.), The Handbook of Group Communication Theory and Research (p. 133). Sage.

House, R. J., & Mitchell, T. R. (1974). Path-Goal Theory of Leadership. Journal of Contemporary Business 3, 81–97.

Janis, I. L. (1972). Victims of Groupthink: A Psychological Study of Foreign-Policy Decisions and Fiascos. Houghton Mifflin.

Karau, S. J., & Williams, K. D. (1993). Social Loafing: A Meta-Analytic Review and Theoretical Integration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 65(4), 681.

Lewin, K., Lippitt, R., & White, R. K. (1939). Patterns of Aggressive Behavior in Experimentally Created ‘Social Climates.’ Journal of Social Psychology 10(2), 269-299.

Pavitt, C. (1999). Theorizing about the Group Communication-Leadership Relationship. In Frey, L. R. (Ed.), The Handbook of Group Communication Theory and Research, (p. 313). Sage.

Solansky, S. T. (2011). Team Identification: A Determining Factor of Performance. Journal of Managerial Psychology 26(3), 250.

Tuckman, B. W., & Jensen, M. A. C. (1977). Stages of Small-Group Development Revisited. Group and Organizational Studies, 2(4), 419–27.

Wood, J. T. (1977). Leading in Purposive Discussions: A Study of Adaptive Behavior. Communication Monographs 44(2), 152-165.

Licensing and Attribution: This chapter is an adaptation of:

- 8.4: Leadership and Small Group Communication in Competent Communication 2e by Lisa Coleman, Thomas King, & William Turner, and is licensed CC BY-NC-SA.

- 8.5: Problem Solving and Decision-Making in Groups in Competent Communication 2e by Lisa Coleman, Thomas King, & William Turner, and is licensed CC BY-NC-SA.

- 13.1: Understanding Small Groups in Communication in the Real World – An Introduction to Communication Studies, by Anonymous, and is licensed CC BY-NC-SA.

- 13.2: Small Group Development in Communication in the Real World – An Introduction to Communication Studies by Anonymous, and is licensed CC BY-NC-SA.

- 13.3: Small Group Dynamics in Communication in the Real World – An Introduction to Communication Studies by Anonymous, and is licensed CC BY-NC-SA.

- 14.3: Problem Solving and Decision Making in Groups in Communication in the Real World – An Introduction to Communication Studies by Anonymous, and is licensed CC BY-NC-SA.

It has been remixed with original content and is licensed CC BY-NC-SA.

A decentralized group communication pattern where each member connects with two others, forming a loop. Promotes collaboration and equal participation.

A centralized communication pattern in which all group members communicate through a central figure, often a leader or coordinator.

A group communication pattern where one central member controls or facilitates all communication, such as in a “wheel” formation.

Decision-making and communication are distributed among group members, typically allowing for more collaboration, shared leadership, and problem-solving.

A characteristic of group work in which members rely on each other to accomplish shared tasks or goals.

A group formed primarily to complete a specific goal or accomplish a task, such as planning an event or solving a problem.

A group formed primarily to provide emotional support, connection, and a sense of belonging among members. These groups prioritize interpersonal relationships over task completion and include friend circles, support groups, and informal social networks.

A group that interacts and collaborates primarily through digital or online communication platforms.

Connections that are formed and maintained through online communication platforms like social media, video calls, or messaging apps.

The idea that a group can achieve more collectively than individuals could achieve on their own.

A phenomenon where individuals contribute less effort in a group than they would when working alone.

A five-stage model of group development, describing how groups form, experience conflict, establish norms, perform tasks, and eventually disband.

The sense of belonging, trust, and commitment that members feel toward their group. High cohesion strengthens collaboration, motivation, and group identity.

The emotional tone or atmosphere of a group, shaped by communication patterns. A positive climate feels supportive, inclusive, and respectful, while a negative climate may feel tense or dismissive.

The process by which new group members learn the rules, norms, and expectations necessary to function effectively within a group.

The tendency for group members to align with shared norms or expectations, often due to internal or external pressures.

A communication pattern in which the desire for harmony or conformity leads a group to suppress dissent and make flawed decisions

Disagreements about how a group operates, such as scheduling, roles, or decision-making processes.

Disagreements over group tasks, goals, or ideas. It can lead to improved outcomes when managed constructively.

Disagreements rooted in personality clashes, communication styles, or values. Often the most emotionally charged type of group conflict.

A collection of three to about fifteen people who interact regularly, share a common purpose, and influence one another.

A leader formally chosen or assigned by an organization or group. Their effectiveness often depends on group acceptance and their ability to guide and support others.

A group member who gains leadership status informally through their behavior, communication, and contributions rather than through appointment.

A leadership style in which the leader makes decisions unilaterally, with little or no input from group members. This style can be efficient but may limit collaboration and creativity.

A leadership style that encourages participation, collaboration, and shared decision-making. The leader guides the process but values input from all group members.

A leadership style marked by low levels of involvement and guidance, allowing group members to make decisions independently. While it can foster autonomy, it may lead to confusion or a lack of direction if group members need support.

A leadership style that provides clear direction, sets expectations, and guides group members closely, especially useful in unfamiliar or high-pressure situations.

A leadership style that encourages group involvement in decision-making, aligning personal goals with the team’s purpose.

A leadership style that emphasizes group members’ well-being by offering encouragement, understanding, and open communication.

A leadership style that sets high standards, challenges group members to excel, and motivates through a shared vision of success.

A set of relationships or connections among individuals or groups that influence communication patterns, information flow, and social influence.