7. Interpersonal Communication in Social Contexts

Overview

Our relationships, whether romantic, professional, or platonic, are shaped by the ways we communicate. In this chapter, we’ll explore how communication builds and sustains relationships in different settings, from personal conversations to workplace interactions. (MLO1, MLO3)

We’ll start by examining the social and cultural norms that guide face-to-face communication. Whether it’s how we greet a coworker, navigate a disagreement with a friend, or express affection in a romantic relationship, these norms influence how we interact and what is considered acceptable or “normal” in different contexts. (MLO1)

Next, we’ll explore strategies for managing conflict through effective communication. Conflict is a natural part of human interaction, but the way we communicate during conflicts can either deepen understanding or create further divisions. You’ll learn practical approaches to handling disagreements, negotiating needs, and maintaining relationships even when challenges arise. (MLO2)

Finally, we’ll look at how communication builds and sustains relationships in personal and professional settings. Whether you’re giving feedback at work, expressing empathy with a friend, or building trust in a team, communication plays a central role in how we connect with others—and how we understand ourselves. (MLO3)

By the end of this chapter, you’ll be able to identify the social and cultural norms that shape face-to-face communication (MLO1), apply strategies for resolving conflict through effective communication (MLO2), and explain how communication builds and sustains personal and professional relationships (MLO3).

Module Learning Outcomes

By the end of this chapter, students will have had the opportunity to:

- Identify the social and cultural norms that shape face-to-face communication. (MLO1)

- Apply strategies for resolving conflict through effective communication. (MLO2)

- Explain how communication builds and sustains personal and professional relationships. (MLO3)

These Module Learning Outcomes align with CLOs 1, 2, and 4 and ULOs 1, 3, and 6. See the Introduction for more details.

Interpersonal Communication and You

Our relationships shape who we are. Maybe you’ve recently transitioned from high school to college and noticed how friendships shift when people move away. Maybe you’ve built new connections on campus while adjusting to changes in your family dynamics. Staying in touch across distance can be challenging, and growing up means creating new relationships while maintaining old ones. All these experiences reflect the importance of interpersonal communication—the everyday interactions that connect us with others.

What is Interpersonal Communication?

Interpersonal communication happens when two or more people in a close relationship exchange messages and get to know one another as individuals. It’s not just small talk with a stranger or a quick nod to a classmate. It’s the kind of communication that builds understanding, trust, and connection, whether it’s catching up with a friend over lunch, texting your sibling about a shared memory, or talking with a parent about your day.

We’ll explore how interpersonal communication shapes three key types of relationships: friendships, romantic relationships, and family relationships. We’ll also dive into conflict—a natural part of any close relationship—and strategies for managing it effectively. Before we explore scientific relationship types, we’ll examine two foundational concepts that shape how we connect with others: self-disclosure and communication climate. These tools help us build trust, navigate emotional intimacy, and respond to conflict in healthier ways.

Foundations of Interpersonal Communication

Understand Self-Disclosure

Think about the last time you told someone something they didn’t already know about you. Maybe you shared your love for photography or your dream of studying abroad. That’s self-disclosure—the process of sharing personal information with others to build connection and trust.

Self-disclosure isn’t just about spilling secrets; it’s about gradually opening up. For example, telling someone you have brown hair isn’t self-disclosure—they can see that. But sharing that you struggle with anxiety, or that you hope to run a marathon someday, reveals something personal.

As relationships deepen, self-disclosure often grows in both breadth (covering more topics) and depth (sharing more personal details). For instance:

- You might start by talking about your major (a fact).

- Then share your opinion on a topic, like your stance on climate change.

- Eventually, you may express feelings, like excitement about a project or sadness over a breakup.

In friendships and romantic relationships, self-disclosure is key to building intimacy. In professional settings, it can help create a positive, collaborative environment, but it’s important to stay mindful of boundaries and the context.

The Rule of Reciprocity

Self-disclosure relies on reciprocity–the mutual exchange of personal information that helps build trust and connection. When you share something meaningful about yourself, the other person often responds by revealing something in return. This reciprocal sharing fosters a sense of balance and equality in the relationship.

Without reciprocity, a relationship can start to feel one-sided or emotionally uneven. For instance, if you open up to a friend about your fears or challenges but they only respond with surface-level topics like the weather, you might feel exposed or unsupported. Being aware of reciprocity helps you navigate conversations more thoughtfully, ensuring that emotional sharing feels safe and mutual.

Self-Disclosure and Social Media

Our willingness to share personal information, our moods, political beliefs, relationship status, and even our location has increased dramatically in the age of social media. Platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok make it easy to stay connected, but they also blur the boundaries between public and private life. What used to be private, like sharing your weekend plans or personal opinions, is now often broadcast to hundreds or even thousands of people.

This shift has raised important questions about privacy and the consequences of self-disclosure. For instance, Kornblum (2007) observed how digital natives (those who grew up with social media) often blend their private and public selves in ways that older generations may find surprising. Some colleges even offer workshops to help students manage their online presence, emphasizing the importance of protecting one’s digital footprint.

There are real-world consequences when self-disclosure goes wrong. A University of Texas football player was removed from the team after making racist comments about the president on social media, and a student at a private Christian college was expelled after photos of him dressed in drag surfaced on Facebook (Nealy, 2009). These examples highlight how self-disclosure can impact relationships, reputation, and even opportunities.

Privacy concerns extend beyond individuals; parent-child dynamics are also shifting. As more parents join platforms like Facebook, students are navigating the awkward balance between openness and privacy. Websites like Oh Crap. My Parents Joined Facebook reflects this tension, as students adjust to family members seeing posts that were once meant only for friends.

Real-World Example: Self-Disclosure in Online Communities

In the Facebook group “Are We Dating the Same Guy?”, women use self-disclosure to warn others about men they are dating—posting names, photos, and personal stories to flag concerning behavior. For some, this open exchange feels empowering, offering solidarity and a sense of protection. But others raise concerns about fairness, accuracy, and unintended consequences. In one case, a man discovered his name and image had been posted alongside unverified allegations. Though the claims were never confirmed, he reported experiencing anxiety, reputational harm, and social fallout.

This moment reveals how self-disclosure plays out differently in digital spaces:

- Women sharing stories use self-disclosure as a form of collective protection and advocacy.

- The digital nature of the platform blurs public and private boundaries, allowing personal information to circulate widely and rapidly.

- The man’s experience highlights how secondhand disclosures—especially when unverified—can have serious effects on someone’s identity and relationships.

This example shows:

- Online self-disclosure can strengthen community bonds and surface important conversations, but it also raises ethical concerns about consent and harm.

- Communication in digital spaces spreads quickly, making the consequences of sharing more complex and far-reaching.

- The impact of disclosure isn’t just about the speaker—it can affect others in ways they never agreed to or anticipated.

Reflection Prompt:

Have you ever seen personal information shared online that made you pause, either because it felt helpful or because it raised questions about consent or privacy? How do you think platforms and participants should balance openness with accountability?

Johari Window

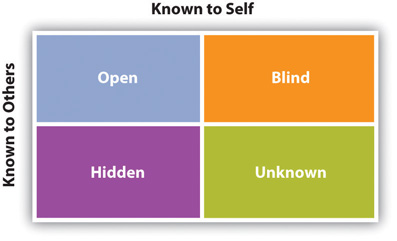

The Johari Window is a communication model designed to help improve interpersonal communication skills. The name Johari Window is a matrix (see Figure 7.1) that comes from combining the first names of the window’s creators, Joseph Luft and Harry Ingham. It is used in communication classes as well as some businesses to help people think about differences in how they see themselves and how others see them. The window is divided into four quadrants or “panes”: the open area or pane, the blind spot, the hidden area or façade, and the unknown. The size of each of the four areas or window panes varies depending on whom you are communicating with and the context of the communication.

| Johari Window Area | What it Means | Examples | How it Changes in Relationships |

|---|---|---|---|

| Open Area | Information you know about yourself and others know too. | Your name, hobbies you share openly. | Expands as you build trust and self-disclosure over time. |

| Blind Area | Things others see in you, but you may not be aware of. | Nervous habits, tone of voice under stress. | Shrinks when you seek feedback and learn about your blind spots. |

| Hidden Area | Things you know but choose not to share with others. | Past mistakes, private beliefs, and family history. | Shrinks as you decide to share personal information with others. |

| Unknown Area | Aspects of yourself that no one knows, not even you. | Hidden talents, future reactions to life events. | It can change as you try new experiences and learn about yourself. |

The Johari Window reminds us that self-disclosure is a choice. As relationships deepen, we tend to expand the Open Area by sharing more about ourselves. At the same time, feedback from others helps shrink our Blind Area, helping us become more self-aware. By reflecting on what we share, hide, or don’t yet know about ourselves, we can communicate more authentically and build stronger connections.

Creating Your Own Johari Window

The Johari Window is a tool for exploring how you see yourself and how others see you. It helps you understand your strengths, blind spots, and areas for growth. You can create your own Johari Window by following these steps (adapted from The World of Work Project, n.d.):

- Choose your collaborator(s): Pick a trusted friend, family member, or colleague who knows you well.

- Select your words: From the list below, choose 5–10 words that best describe you.

- Get feedback: Ask your collaborator(s) to select 5–10 words they think describe you.

- Plot your results:

- Words you both selected go in the Open pane.

- Words only you selected go in the Hidden pane.

- Words only others selected go in the Blind pane.

- Remaining words go in the Unknown pane.

- Reflect: How do your choices align with others’ views? Are there surprises? Are there areas for growth?

Possible words to choose from when creating your own Johari Window:

- Able

- Accepting

- Adaptable

- Bold

- Brave

- Calm

- Caring

- Cheerful

- Clever

- Complex

- Confident

- Dependable

- Dignified

- Energetic

- Extroverted

- Friendly

- Giving

- Happy

- Helpful

- Idealistic

- Independent

- Ingenious

- Intelligent

- Introverted

- Kind

- Knowledgeable

- Logical

- Loving

- Mature

- Modest

- Nervous

- Observant

- Organized

- Patient

- Powerful

- Proud

- Quiet

- Reflective

- Relaxed

- Religious

- Responsive

- Searching

- Self-Assertive

- Self-Conscious

- Sensible

- Sentimental

- Shy

- Silly

- Spontaneous

- Sympathetic

- Tense

- Trustworthy

- Warm

- Wise

- Witty

Source: Introduction to Personal Communication in Competent Communication by Lisa Coleman, Thomas King, & William Turner, and is licensed CC BY-NC-SA.

Once you’ve completed your Johari Window, think about what it reveals. Are there blind spots you didn’t expect? Are there strengths you hadn’t fully recognized? This reflection can help you become a more self-aware communicator, build stronger relationships, and approach conversations with empathy and openness.

Communication and Friendships

Friendships are voluntary interpersonal relationships between two people who typically see each other as equals and influence one another in meaningful ways. Friendships play a key role in meeting our fundamental need for connection. While the meaning of friendship can vary depending on age, gender, and cultural background, what all friendships have in common is that they are relationships we choose. Some friendships grow so close that they feel like family, while others may be short-term but still meaningful.

Throughout your life, you’ll develop and maintain friendships in different ways. As you transition from high school to college or enter new phases of life, you’ll notice how friendships can shift, some friends may stay close, while others may drift apart. Understanding how communication helps build and sustain these relationships is a core part of interpersonal communication.

Stages in Developing Friendships

Friendships don’t usually happen all at once; they grow over time. According to communication scholar William Rawlins (1992), there are six stages we often move through as friendships develop. While we might not follow these steps exactly in every relationship, they provide a helpful guide for understanding how friendships grow and change.

1. Role-Limited Interaction

This is the starting point of many friendships. You meet someone in a specific role, like a classmate, coworker, or teammate, and your conversations focus on small talk or surface-level topics. You might chat about an assignment or the weather, but you’re not sharing personal details yet. For example, two students sitting near each other in class might start talking about how they feel about the course.

2. Friendly Relations

In this stage, your conversations start to go a bit deeper. You might discover shared interests, hobbies, or goals. This is when you decide whether you’d like to keep getting to know the person. For instance, those two students in class might realize they both play basketball or are homesick for family, and they begin to connect beyond school topics.

3. Moving Toward Friendship

Here, you start making small moves to build the relationship, maybe by hanging out outside of class or inviting the person to join an activity. As you spend more time together, you begin to share more personal stories, which helps build trust. For example, one student invites the other to join the campus basketball club, deepening their connection.

4. Nascent Friendship

At this point, you consider each other as friends. You establish your own unique communication patterns, maybe you text each other funny memes or share late-night snacks after studying. The relationship feels more personal, and there’s an expectation of regular communication. You might go from saying, “This person in my class” to “my friend.”

5. Stabilized Friendship

This is when a friendship feels solid and established. You assume you’ll be in each other’s lives, and you trust each other to share both the good and the difficult moments. Even if you move away or don’t see each other as often, the bond remains strong. For example, those students may graduate and live in different places, but they still keep in touch and make an effort to stay connected.

6. Waning Friendship

Not all friendships last forever. Sometimes, friends grow apart due to distance, life changes, or unmet expectations. Maybe you no longer share common interests, or someone breaks an important rule of trust, like sharing your private information with others. While endings can be difficult, it’s part of the natural cycle of relationships.

Challenges for Friendships

Friendships are rewarding, but they can also come with challenges. Three common areas where challenges arise include gender differences, cultural diversity, and sexual attraction. These factors influence how we communicate, often in ways shaped by broader issues of power, privilege, and societal norms. Research shows that people tend to form friendships with others who are similar to themselves, a pattern called homophily, which can make forming diverse friendships more difficult (Echols & Graham, 2013). Understanding these dynamics can help us navigate differences and build stronger, more inclusive relationships.

Gender

Research suggests that both women and men value trust, intimacy, and time spent with friends (Mathews et al., 2006; Bell & Coleman, 1999; Monsour & Rawlins, 2014). However, there are differences in how these interactions typically happen. For example, female friends often get together simply to talk and catch up. Antoinette might say, “Why don’t you come over so we can talk?”—with verbal communication as the central focus of their time together (Coates, 1986; Harriman, 1985). In contrast, male friends often plan an activity as the backdrop for conversation, like John saying, “Hey, Mike, let’s play video games this weekend.” While the invitation focuses on the activity, the shared time often leads to talking, joking, and reinforcing their friendship (Burleson et al., 2005).

It’s important to remember that gender is not a simple binary. While much research has focused on male and female differences, society’s understanding of gender is shifting toward a more inclusive, spectrum-based perspective. As this research expands, new insights into relationship rules and communication patterns will continue to emerge.

Culture

Cultural values shape how we understand and maintain our friendships. In many individualistic cultures, like the United States, friendships are often viewed as voluntary and based on personal choice. We get to decide who we want to spend time with, and if we don’t like someone, we’re not obligated to continue the relationship (Carrier, 1999). In contrast, collectivist cultures, such as Japan and China, tend to place more emphasis on loyalty, duty, and obligation within friendships (Kim & Markman, 2013). In these cultural contexts, friendships often come with expectations around gift-giving, social support, and even job opportunities, which some might see as favoritism in the U.S., but are considered natural expressions of loyalty in collectivist cultures (Carrier, 1999).

These cultural differences can affect communication, including how people express closeness, how often they interact, and what kinds of support they offer. Recognizing these patterns helps us become more thoughtful communicators, especially in diverse social settings.

Sexual Attraction

Sometimes, sexual attraction or tension can create challenges in friendships. You might have a friend who you develop romantic feelings for, or you might navigate conversations about whether to explore a romantic connection. Some people use terms like “friends with benefits” to describe a relationship that blends friendship with occasional physical intimacy, but without the expectations of a committed romantic relationship. It’s important to communicate openly and respectfully in these situations to make sure both people are on the same page.

Romantic Relationships

Romantic relationships are an important part of our lives. Like friendships, they help fulfill our needs for intimacy, connection, and emotional support. In many Western cultures, romantic relationships are voluntary—we typically choose our partners based on attraction, shared interests, and compatibility. However, cultural norms around the world vary. In some cultures, romantic relationships may be arranged by families or influenced by social expectations around class, race, religion, or gender. Even in societies where people have more freedom to choose, factors like family approval, societal norms, and laws can shape who is considered an “acceptable” partner.

Think about your own experiences: Who are you drawn to? Chances are, they’re people you encounter in your everyday life, at school, work, or through hobbies and social circles. Similarity, proximity, and shared identity are powerful influences in who we connect with romantically. We often form relationships with people who reflect our self-concept—heterosexual individuals often date other heterosexual individuals, and LGBTQ+ people often seek out partners who affirm their identity. Race, religion, social class, and cultural background also play a role. While it’s common for people to partner with those who share similar identities, that doesn’t mean we only form relationships with people exactly like us. Social norms around relationships are changing, and interracial, interfaith, and intercultural relationships are becoming more common, especially as technology and online dating expand the pool of potential partners.

Stages of Romantic Relationships

Romantic relationships often follow a series of stages, although not every relationship progresses in the same way. These stages can help us understand how relationships grow, change, and sometimes end.

- No Interaction: Two people have not yet interacted.

- Invitational Communication: We send signals of interest, like smiling, making eye contact, or striking up a conversation.

- Explorational Communication: We spend more time together, share more about ourselves, and test compatibility.

- Intensifying Communication: The “relationship high” stage, where we want to be together all the time. We might idealize our partner and downplay their flaws.

- Revising Communication: The honeymoon phase fades, and we see each other more realistically. This is when couples decide whether to deepen their commitment or move on.

- Commitment: We decide to make the relationship a lasting part of our lives, this could be marriage, a long-term partnership, or another form of commitment.

Long-term relationships also involve navigating the ups and downs of life. As people grow and change, communication needs evolve. Couples must adapt, whether it’s balancing careers, parenting, or managing financial challenges. Open, honest communication is key to navigating these changes together.

It’s important to note that relationships don’t always follow a straight path. Couples may move back and forth between growth and deterioration stages throughout their relationship. What matters is how they communicate and manage those changes together.

Relational Dialectics

Relational dialectics theory helps us understand the tensions that arise in romantic relationships. These tensions are natural and part of navigating a close partnership. Baxter (1990) identifies three key dialectics:

- Autonomy–Connection: Balancing the need for independence with the desire for closeness.

- Novelty–Predictability: Balancing the comfort of routine with the excitement of new experiences.

- Openness–Closedness: Balancing honesty and transparency with the need for privacy.

For example, you might enjoy spending a lot of time with your partner (connection) but still need some alone time to recharge (autonomy). Or you might crave the security of predictable routines but also want surprises to keep things exciting.

There’s no “one-size-fits-all” solution to managing dialectical tensions. Healthy relationships involve communicating openly, being flexible, and finding ways to honor both partners’ needs.

Interpersonal Communication in the Workplace

Work isn’t just about tasks and deadlines; it’s about people. No matter your field, you’ll interact with supervisors, coworkers, and clients. Shows like The Office and The Apprentice use humor to show how communication in the workplace can go wrong, but real-life workplace communication is no joke. Since many of us spend as much time at work as we do with friends and family, the workplace becomes a key setting for building and maintaining relationships.

In this section, we’ll explore the different types of relationships you’ll likely encounter at work, including supervisor-subordinate relationships, workplace friendships, and workplace romances (Sias, 2009).

Supervisor-Subordinate Relationships

Most workplaces are built on hierarchy, which shapes communication. A supervisor-subordinate relationship involves two people, where one has formal authority over the other. This relationship can be built on mentoring, friendship, or even romance, and each comes with its own challenges and rewards (Sias, 2009).

Supervisors play an important role in guiding employees, especially new hires. They share information, provide feedback, and set expectations. Unlike friendships, where communication is often reciprocal, supervisor-subordinate communication is usually one-sided. Supervisors hold information that employees need, and they evaluate performance, which can create power imbalances.

While positive feedback can boost motivation, research shows that supervisors often avoid giving negative feedback, even though it’s essential for growth. Without clear, honest communication, problems may go unaddressed, leading to misunderstandings and frustration.

Workplace Friendships

Not all coworker relationships turn into friendships, but the ones that do can be valuable. Friendships at work can make your job more enjoyable, help manage stress, and even improve job performance. They can also provide emotional support and a sense of belonging (Sias, 2005).

Coworker friendships tend to fall into three categories (Sias, 2005):

- Information Peers: Share work-related information, but little personal connection.

- Collegial Peers: Share some personal details, offer support, and provide feedback.

- Special Peers: Share a deep level of trust, personal disclosure, and emotional support—similar to close friendships outside of work.

These relationships can create informal networks that help you navigate the workplace, but they can also lead to gossip or blurred boundaries if not managed carefully. Workplace friendships are shaped by proximity, similarity, and shared experiences, but like all relationships, they need attention and care.

Real-World Example: Conflict Over Office Relocation

A company announces plans to relocate its headquarters to a sleek, modern facility with perks like a fitness center, upgraded break rooms, and open-concept workspaces. While some employees celebrate the change, others—especially long-term staff—feel frustrated and anxious. For them, the move means longer commutes, a loss of routine, and an unfamiliar environment. In team meetings, tensions emerge: some employees voice their concerns, only to be met with comments like “You’re just afraid of change” or whispers suggesting they should “just find a new job.”

This moment reveals how workplace conflict often reflects deeper dynamics:

- Employees with more influence or social capital may dominate the conversation, framing their preferences as the default or most reasonable.

- Dismissive responses silence valid concerns and reduce psychological safety in the workplace.

- Structural changes, like relocation, disrupt informal networks and shared routines that shape day-to-day communication.

This example shows:

- Workplace conflict isn’t just about disagreement; it reflects power dynamics, identity, and the broader communication climate.

- How concerns are received (or ignored) can affect team cohesion and employee morale.

- Inclusive communication requires listening, empathy, and space for multiple perspectives—even when change seems positive for some.

Reflection Prompt:

Think of a time when a change at work, school, or in a group caused disagreement or tension. How were concerns expressed, and how were they received? What role did communication play in resolving (or deepening) the conflict?

Romantic Workplace Relationships

Workplace romances happen when two people are emotionally and physically attracted to each other. They are controversial and common. Studies show that 75–85% of people have been involved in or witnessed a workplace romance (Sias, 2009). These relationships can boost morale and productivity, but they can also create tension, raise concerns about favoritism, and blur the lines between professional and personal lives.

People enter workplace romances for many reasons, including job-related motives (career advancement), ego motives (validation), or love motives (genuine affection) (Sias, 2009). Regardless of the reason, workplace romances can affect coworkers, spark gossip, and sometimes lead to policy changes.

While some argue that companies shouldn’t interfere in employees’ personal lives, others worry about the impact on workplace culture and productivity. Romantic relationships between supervisors and subordinates can be particularly tricky, as they raise questions about power dynamics, consent, and fairness.

Professionalism in the Workplace

What does it mean to be a professional? It’s more than just holding a job or a title. Being a professional means acting with competence, responsibility, and ethical awareness—whether you’re a lawyer, nurse, welder, or teacher.

A profession is a field that requires specialized knowledge and skills, often gained through training, education, or hands-on experience. Becoming a professional doesn’t happen overnight. It takes time and commitment to master the tools, language, and expectations of a particular field.

Professionalism, then, is about more than what you know. It’s how you carry yourself at work—communicating clearly, collaborating respectfully, meeting deadlines, and handling challenges with integrity. Different professions may define professionalism in slightly different ways, but the core idea is the same: professionalism means taking your role seriously, being reliable, and contributing to the success of your team or organization.

What Does Professionalism Look Like?

Professionalism isn’t one-size-fits-all. It can vary by field, but most professionals share some key behaviors:

- Acting ethically: Following rules, respecting others, and doing the right thing—even when no one’s watching.

- Respecting others: Listening, collaborating, and treating everyone fairly, regardless of their background or position.

- Communicating effectively: Using clear, professional language in writing and speaking, and adapting your communication to different audiences and situations.

- Taking responsibility: Owning your mistakes, following through on commitments, and learning from feedback.

- Working toward shared goals: Contributing to the success of your team and organization.

Ethical Communication

Ethics in communication means being honest, respectful, and fair. Communication scholar W. Charles Redding (1996) identified several ways communication can be unethical in organizations:

- Coercive communication: Using threats, manipulation, or pressure.

- Destructive communication: Insults, rumors, or attacks on someone’s character.

- Deceptive communication: Lying, misleading, or hiding the truth.

- Intrusive communication: Violating privacy, like secretly recording or spying.

- Secretive communication: Withholding important information.

- Manipulative communication: Using fear, bias, or misinformation to gain compliance.

These behaviors damage trust, harm relationships, and create toxic workplaces. Professionalism means avoiding these pitfalls and building communication that’s ethical, clear, and constructive.

Respect in the Workplace

Respect is the foundation of healthy workplace relationships. Here are some ways to show respect:

- Be polite, kind, and inclusive.

- Avoid interrupting, eye-rolling, or dismissing others’ ideas.

- Listen carefully and without judgment.

- Treat everyone fairly, regardless of gender, race, religion, age, or other identities.

- Speak up for fairness and equity when you see discrimination or bias.

The Language We Use Matters

Professionalism also means being mindful of the words we choose. Sometimes, common phrases can carry unintended bias. For example, saying someone was “grandfathered in” can unintentionally reinforce gender bias. Being aware of language—whether it’s gendered, ableist, or otherwise exclusive—helps create a workplace where everyone feels respected.

Unconscious biases can affect our language and behavior, even when we don’t mean harm. Lee (2016) explains that our brains automatically categorize people and assign emotional labels, often without our awareness. These biases can lead to microaggressions—subtle, often unintentional slights or insults directed at marginalized groups (Wing, 2010). Recognizing and challenging these patterns is an important part of professionalism.

Taking Personal Responsibility

Being professional means owning your choices, actions, and growth. This doesn’t mean ignoring systemic barriers like racism, sexism, or ableism; it means recognizing what you can control and working to improve. Here are some ways to practice personal responsibility:

- Take ownership of your thoughts, feelings, and actions.

- Acknowledge when you make a mistake, and learn from it.

- Focus on your professional goals and take steps to reach them.

- Be proactive in seeking feedback and improving your skills.

- Avoid blame-shifting or making excuses; take accountability for your part.

Excuses happen, but in the workplace, they can harm your reputation and relationships. Studies show that constant excuse-making can frustrate coworkers and supervisors, and it may even impact customer trust (Hill, Baer, & Kosenko, 1992; Bellizzi & Norvell, 1991). When things go wrong, a professional focuses on solutions, not excuses.

Language Skills Matter

Finally, professionalism is about how you communicate. Studies show that strong communication skills—writing clearly, speaking effectively, and adapting your style to different situations—are among the most important traits employers seek (PayScale, 2016). Whether it’s an email, a team presentation, or a conversation with a client, your words and tone reflect your professionalism.

Discussion

As we’ve explored throughout this chapter, communication is not just about exchanging information—it’s about how we build and sustain relationships, how we navigate conflict, and how we express ourselves in different social settings. Every interaction is shaped by social norms, cultural expectations, and power dynamics, whether we’re sharing a secret with a close friend, resolving a disagreement at work, or deciding how much of ourselves to share on social media.

Let’s take a moment to reflect on how these ideas connect to your own life and experiences.

Interpersonal Communication in Everyday Life

Discussion Prompt:

Think of a time when your communication choices impacted a relationship, whether positively or negatively. This could be a conversation with a friend, family member, romantic partner, or coworker. Maybe you had to decide whether to speak up during a conflict, how much personal information to share, or how to balance openness with privacy.

What happened? How did social and cultural norms influence your communication in that situation? How did your words, tone, or body language affect the outcome of the interaction?

Follow-up Question:

Consider how power, privilege, or difference shaped the communication dynamic. Did someone’s role, status, or identity give them more influence or voice in the conversation? How did you navigate that? Looking back, would you handle the situation the same way, or would you approach it differently based on what you now know about interpersonal communication?

Conclusion and Key Takeaways

Communication is at the heart of all our relationships. Whether we’re navigating friendship, romance, or workplace dynamics, how we speak, listen, and respond shapes the quality of our connections. In this chapter, we explored how face-to-face communication, conflict management, and trust-building reflect cultural norms and personal experiences. Strong relationships aren’t built on perfect communication but on efforts to understand, adapt, and care.

Key Takeaways

- Face-to-face communication is shaped by social norms around politeness, power, and emotional expression. (MLO1)

- Effective conflict resolution involves empathy, listening, and a willingness to find shared understanding. (MLO2)

- Personal and professional relationships thrive when communication is clear, respectful, and responsive to others’ needs. (MLO3)

- Power dynamics, workplace roles, and cultural expectations all influence how we connect with others. (MLO1, MLO2, MLO3)

Check Your Understanding

References

Baxter, L. A. (1990). Dialectical contradictions in relational development. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 7, 69-88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407590071004

Bell, S., & Coleman, S. (1999). The anthropology of friendship: Enduring themes and future possibilities. The Anthropology of Friendship. Berg.

Bellizzi, J. A., & Norvell, D. (1991). Personal characteristics and salesperson’s justifications as moderators of supervisory discipline in cases involving unethical salesforce behavior. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 19, 11-16. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02723419

Burleson, B. R., Holmstrom, A. J., & Jones, S. M. (2005). Some consequences for helpers who deliver ‘cold comfort’: Why it’s worse for women than men to be inept when providing emotional support. Sex Roles, 53(3/4), 153-172.

Carrier, J. G. (1999). People who can be friends: Selves and social relationships. In Sandra Bell and Simon Coleman (Eds), The Anthropology of Friendship (pp. 21-28). Berg.

Coates, J. (1986). Women, men, and language: A sociolinguistic account of sex differences in language. Longman.

Echols, L., & Graham, S. (2013). Birds of a Different Feather: How Do Cross-Ethnic Friends Flock Together? Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 59(4), 461–488. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259728067_Birds_of_a_Different_Feather_How_Do_Cross-Ethnic_Friends_Flock_Together?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Harriman, A. (1985). Women/men/management. Praeger.

Hill, D. J., Baer, R., & Kosenko, R. (1992). Organizational characteristics and employee excuse making: Passing the buck for failed service encounters. Advances in Consumer Research, 19, 673-678.

Kim, K., & Markman, A. (2013). Individual differences, cultural differences, and dialectic conflict description and resolution. International Journal of Psychology, 48(5), 797-808.

Lee, B. (2016). A mindful path to a compassionate cultural diversity. In M. Chapman-Clarke (Ed.), Mindfulness in the workplace: An evidence-based approach to improving wellbeing and maximizing performance (pp. 266-287). Kogan Page.

Monsour, M., & Rawlins, W. K. (2014). Transitional identities and postmodern cross-gender friendships: An exploratory investigation. Women & Language, 37(1), 11-39.

Rawlins, W. K. (1992). Friendship Matters: Communication, Dialectics, and the Life Course. Routledge.

Redding, W. C. (1996). Ethics and the study of organizational communication: When will we wake up? In J. A. Jaksa & M. S. Pritchard (Eds), Responsible communication: Ethical issues in business, industry, and the professions (pp. 17-40). Hampton Press.

Sias, P. M. (2005). Workplace relationship quality and employee information experiences. Communication Studies, 56(4), 377.

Sias, P. M. (2009). Organizing relationships: Traditional and emerging perspectives on workplace relationships (p. 2). Sage.

Wing, D. (2010, November 17). Microaggressions in everyday life: More than just race — Can microaggressions be directed at women or gay people? Psychology Today

Licensing and Attribution: This chapter is an adaptation of:

- 6.1: Introduction to Personal Communication in Competent Communication by Lisa Coleman, Thomas King, & William Turner, and is licensed CC BY-NC-SA.

- 6.3: Friendships in Competent Communication by Lisa Coleman, Thomas King, & William Turner, and is licensed CC BY-NC-SA.

- 6.4: Romantic Relationships in Competent Communication by Lisa Coleman, Thomas King, & William Turner, and is licensed CC BY-NC-SA.

- 7.5: Relationships at Work in Communication in the Real World by University of Minnesota, and is licensed CC BY-NC-SA, except where otherwise noted.

- 8.2: Workplace Communication in Exploring Relationship Dynamics by Maricopa Community Colleges, and is licensed CC BY-NC-SA.

It has been remixed with original content and is licensed CC BY-NC-SA.

The exchange of messages between people in close relationships, used to build understanding, trust, and connection.

The process of sharing personal information with others to build trust and intimacy in relationships.

The emotional tone of a relationship or group, shaped by how people feel valued, respected, and supported in their interactions.

The expectation that personal sharing in relationships is mutual, helping maintain balance and connection.

A communication model with four areas—open, blind, hidden, and unknown—that illustrates how self-awareness and feedback influence relationships.

Part of the Johari Window; information known to both self and others.

Part of the Johari Window; traits others see in us that we don’t see in ourselves.

Part of the Johari Window; personal information we know about ourselves but choose not to share.

Part of the Johari Window; aspects of ourselves that are unknown to both self and others.

A voluntary interpersonal relationship marked by trust, affection, and mutual influence.

The tendency to form relationships with people who are similar to us in background, beliefs, or identity.

Cultures that emphasize personal autonomy, individual achievement, and self-expression. In individualistic cultures, people are encouraged to prioritize personal goals over group goals and define their identity through individual traits and accomplishments. Examples include the United States, Canada, and many Western European countries.

Cultures that emphasize group harmony, interdependence, and collective well-being. In collectivist cultures, people are encouraged to prioritize group goals over personal desires and define their identity through relationships, roles, and group membership. Examples include Japan, China, and many Latin American and African countries.

Tensions or opposing needs that arise in close relationships, such as autonomy vs. connection.

The influence, relationships, and informal power someone holds in a group or organization, which can shape how their voice is received.

Behaviors and attitudes that reflect reliability, respect, ethical conduct, and effective communication in a work setting.

Communication that is honest, respectful, fair, and mindful of the impact on others.

Professional connections between colleagues, shaped by roles, communication norms, and power dynamics.

Subtle, often unintentional comments or behaviors that reinforce stereotypes or marginalize people based on identity.