4. Design Surveys Using Evidence-Based Principles

4.1 Survey questions or statements written in positive or negative wording

When requesting information from respondents, you can use only positively-worded statements (or questions) or a mix of positively- and negatively-worded statements (or questions). (Hereafter, for simplicity we will refer to both statements and questions as statements.)

4.1.1 Using only positively- or negatively-worded statements

Survey questionnaires commonly use positively-worded statements. To write one, frame the statement in terms of desirable conditions or outcomes related to the construct being measured.

For example, think about the desirable outcomes of customer service you provide. You want the customers to feel like the service was completed professionally and in a timely manner, and you want them to feel satisfied with the service provided. Using those positive attributes that represent the quality of the service, you would develop the following positively-worded statements:

The service was professionally provided.

The service was completed in a timely manner.

I am satisfied with the service provided.

These statements reflect positive attributes that represent quality customer service.

Likely, if you’re measuring the usability of a learning management system, you might use:

The menu items are intuitive.

The navigation structure is user-friendly.

But, should you use only positively-worded statements? Or should you mix positively- and negatively-worded statements?

Some researchers advise against using a mix of positively- and negatively-worded statements in a single survey, for the following reasons:

- Respondents may misread negatively worded items and choose a wrong response, leading to threats to data validity (Weem, Onwuegbuzie, & Lustig, 2003[1])

- Mixing both types of statements can reduce construct validity. For example, in factor analysis, negatively-worded survey items may load onto a separate factor, not because of conceptual differences, but simply due to wording difference (Salazar, 2015[2]).

4.1.2 When mixing positively and negatively-worded statements

There are situations where it is appropriate to include negatively-worded statements.

- You may include negatively-worded items when the survey topic itself is negative in nature, such as in surveys measuring depression or anxiety:

I feel hopeless.

I cannot stop worrying about different things.

- When conducting a cause analysis or analyzing organizational culture, you may find yourself wanting to use a few negatively-worded statements to specifically assess areas of concern or dysfunction.

- You may also use a balanced scale, which includes an equal number of positively- and negatively-worded items, which can reduce acquiescence bias (Baumgartner & Steenkamp, 2001[3]; Cloud & Vaughan, 1970[4])—the tendency for some respondents to consistently agree (or disagree) with statements regardless of their content (Cronbach, 1942[5]).

- Including both positively- and negatively-worded items also helps you detect careless responding. For example, when a respondent agrees with a positively-worded statement such as “I like it” and its opposite “I dislike it”, it suggests that the respondent did not pay attention when selecting options. In such cases, you might decide to treat this respondent’s data as invalid and exclude it from analysis. If you decide to include negatively-worded statements in your survey, you will need to choose between wording approaches (see Table 3):

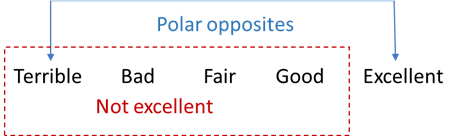

- Polar opposites – using directly opposite terms (e.g., Excellent vs. Terrible)

- Negated positives – adding “not” to the positive term (e.g., Excellent vs. Not excellent)

- Double negatives – adding “not” to the opposite term (e.g., Excellent vs. Not terrible)

- It is not advisable to use double-negative statements, as they unnecessarily increase cognitive load, cause confusion, and possibly result in incorrect data. Therefore, we will exclude double-negatives from further discussion.

So, which should you use—polar opposites or negated positives? Different researchers seem to have different opinions about this issue (e.g., Schriesheim & Hill, 1981[6], Weijters & Baumgartner, 2012[7]).

The choice may depend on the survey context, the type of respondents, and the clarity of wording.

Table 3 Positives, Polar Opposites, Negated Positives, and Double-Negatives

| Wording | Ingredient | Type |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Excellent | A positive word | Positively worded |

| 2. Terrible | The polar opposite of the positive word | Negatively worded |

| 3. Not excellent | “Not” the positive word (a.k.a. negated positive) | Negatively worded |

| 4. Not terrible | “Not” the polar opposite word (a.k.a. double-negative)* | Negatively worded |

While choosing between Terrible and Not excellent as the negative wording, it is important to think about whether the two convey the same meaning.

The service was terrible.

The service was not excellent.

Although both have a negative meaning of Excellent, Not excellent is not exactly the same as Terrible. Terrible is the polar opposite of Excellent while Not excellent simply refers to anything less than Excellent, which could include Good, Fair, Bad, and Terrible (as illustrated in Figure 17). Therefore, in this case, it would be more precise to use the polar opposite, Terrible, as the negative wording.

Figure 17 Polar Opposites vs. Negated Positives

In other cases, especially when using dichotomous descriptors such as Clear vs. Unclear or True vs. Untrue, negated positives may convey nearly the same meaning as the polar opposites. In these situations, either statement can effectively serve the purpose:

The objectives are not clear. (negated positive)

The objectives are unclear. (polar opposite)

However, using a polar opposite is not always a better option. In some cases, it may shift the intended meaning of the item. For example, although Misunderstand is technically the polar opposite of Understand, a more appropriate negative phrasing might be Feel confused.

The examples helped me understand the concept.

The examples caused me to misunderstand the concept.

The examples made me feel confused about the concept.

Table 4 presents sample sets of commonly used positive wordings in surveys and their corresponding polar opposites.

Table 4 Sample Sets of Positive and Polar Opposite Wording

| Positive | Polar opposite | Positive | Polar opposite |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agree | Disagree | Helpful | Unhelpful |

| Appropriate | Inappropriate | High (quality) | Low (quality) |

| Comfortable | Uncomfortable | Improve | Worsen |

| Competent | Incompetent | Interesting | Boring |

| Correct | Incorrect | Like | Dislike |

| Easy | Difficult | Likely | Unlikely |

| Effective | Ineffective | Relevant | Irrelevant |

| Fast (service) | Slow (service) | Satisfied | Dissatisfied |

| Friendly | Unfriendly | Supportive | Unsupportive |

| Good | Bad | Useful | Useless |

| Happy | Unhappy | Well done | Poorly done |

4.1.3 Designing negatively-worded statements with reverse-coding in mind

When using negatively worded statements, it’s important to plan for reverse-coding if you intend to compare them with positively worded items. For example, suppose you used the following two survey items to detect careless responses. You would reverse-code the data obtained from the negatively-worded item.

| [Positively-worded] | [Negatively-worded and reverse-coded] |

|---|---|

| I received excellent service.

○ Strongly disagree (1) ○ Somewhat disagree (2) ○ Neutral (3) ○ Somewhat agree (4) ○ Strongly agree (5) |

I received terrible service.

○ Strongly disagree (5) ○ Somewhat disagree (4) ○ Neutral (3) ○ Somewhat agree (2) ○ Strongly agree (1) |

In data from careful respondents, you would expect the reverse-coded values to match or at least closely align with those from the corresponding positively worded items. For example, “I strongly agree that I received excellent service (5)” may correspond with “I strongly disagree that the I received terrible service (5).”

Even when you include negatively-worded statements without the specific intention of screening careless responses, you may still need to reverse-code the responses to those items. Doing so will help avoid confusion during your analysis and reporting.

| [Positively-worded] | [Negatively-worded and reverse-coded] |

|---|---|

| I am satisfied with the inventive plan.

○ Strongly disagree (1) ○ Somewhat disagree (2) ○ Neutral (3) ○ Somewhat agree (4) ○ Strongly agree (5) |

I feel gender bias when it comes to promotion.

○ Strongly disagree (5) ○ Somewhat disagree (4) ○ Neutral (3) ○ Somewhat agree (2) ○ Strongly agree (1) |

In summary, you want to keep in mind the following principles when deciding to use positively- and/or negatively-worded statements:

- Be aware of possible issues associated with mixing positively- and negatively-worded statements (e.g., threats to construct validity).

- Develop positively-worded statements that describe the desirable conditions or outcomes of what is being measured.

- When mixing negatively-worded statements with positively-worded statements, carefully choose either polar opposites or negated positives, and ensure that the reverse-coded data closely match that of positively-worded statements.

- Do not use double-negatives.

- Weem, G. H., Onwuegbuzie, A. J., Lustig, D. (2003). Profiles of respondents who respond inconsistently to positively- and negatively-worded items on rating scales. Evaluation & Research in Education, 17(1), 45-60. ↵

- Salazar, M. S. (2015). The dilemma of combining positive and negative items in scales. Psicothema, 27(2), 192-199. ↵

- Baumgartner, H., & Steenkamp, J-B. E. M. (2001). Response styles in marketing research: A cross-national investigation. Journal of Marketing Research, 38(2), 143-156. ↵

- Cloud, J., & Vaughan, G. M. (1970). Using balanced scales to control acquiescence. Sociometry, 33(2), 193-202. ↵

- Cronbach, L. J. (1942). Studies of acquiescence as a factor in the true-false test. Journal of Educational Psychology, 33(6), 401-415. ↵

- Schriesheim, C. A., & Hill, K. D. (1981). Controlling acquiescence response bias by item reversals: The effect on questionnaire validity. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 41, 1101–1114. ↵

- Weijters, B., & Baumgartner, H. (2012). Misresponse to reversed and negated items in surveys: A review. Journal of Marketing Research, 49(5), 737-747. ↵