9 Early Roman Drama and Theatre

Early Roman Drama and Theatre

I. Introduction: An Overview of Roman Drama

As Rome begins and ends with Romuli, so its drama and theatre also come full circle across the ages. Traditionally, there are three major phases of development:

1) an early period (pre-240 BCE) when native Italian drama,

such as Atellan farces, phlyaces and Fescennine verses, dominated

the Roman stage;2) the period of literary drama (240 BCE – ca. 100 BCE),

when the Romans primarily adapted classical and post-classical Greek plays;3) the renaissance of popular entertainment (ca. 100 BCE

– 476 CE), when traditional Roman fare like circuses, spectacles and mime

returned to the forefront of the entertainment scene.

The third phase is far and away the longest, encompassing all of Roman history from its highest point in the first century BCE to the civilization’s so-called “Decline and Fall” in the fifth century CE. Arguably, a fourth phase could be added, namely, Byzantine entertainments which centered on mime and chariot races, essentially an extension of the preceding period of popular entertainment. Thus, it is clear Roman tastes gravitated toward circuses, sports and broad comedies making those Hellenized Latin dramas, on which our attentions primarily rest today—they constitute the vast majority of surviving scripts—littlemore than a brief intermission in the form of entertainment the vast majority of Romans preferred over time: spectacle.

At first glance, Roman theatre history presents a fundamental problem: the evidence for theatre does not coincide with that for drama. That is, the majority of texts we have today derive from the second phase (the age of literary drama in the second and third centuries BCE), whereas all extant Roman theatres date significantly later and may not even have been constructed for dramatic performances at all. With that, it is hard to reconstruct the dynamics of Roman stagecraft. While much the same might be said of ancient Greece, it is certain that Greek post-classical theatres were designed for the performance of plays, at least to some extent. At Rome there is no such guarantee.

This discrepancy between the physical and literary evidence stems largely from the two-fold nature of Roman theatre, itself a ramification of the social context of ancient Rome. Literary drama was aimed, for the most part, at the upper classes. Plautus’ comedy, as low-brow as it may look to us, was directed toward an audience willing to listen to words and follow a plot, as opposed to watching acrobats, tightrope-walkers and gladiators.

Terence’s plays go further yet and invite actual contemplation of the human condition, what, no doubt, the Roman tragedies written during the late Republic also did, many of which were based on Greek myth and drama. Unfortunately not a single play of this sort has been preserved intact. Conversely, the great arenas found all over the Roman world, of which the Colosseum is the most visible reminder, housed sporting events and spectacles. Many of these survive, but if they ever served up any theatrical performances at all, it was more likely mime than some genre of classical drama.

Thus, the well regulated and pervasive castes of Roman society—such rigidity was the relic of the early Republic and its conflicts between patricians and plebeians—dictated different types of entertainment for distinct classes of viewers. This is not to say that there was no overlap, only that the segregation of Roman social orders predicated and reinforced different genres of performance. It is an oversimplification, but a very real truth nonetheless, to say that in Rome entertainment was divided between “readers” and “viewers,” that is, a literate nobility and the unwashed mob. Unlike in the Greek world, however, serious drama was able to hang onto the hearts and minds of the Roman public for only a century or so. Thus, in Rome performances focused on the spoken word rose quickly from and sank back almost as fast into the popular entertainment scene, the one and only enduring aspect of Roman theatre history.

II. Native Italian Drama (before 240 BCE)

There is some evidence that the Romans were first exposed to public entertainments not from the Greeks who had colonized southern Italy but the Etruscans to the north. In the sixth and fifth centuries BCE, Etruscan culture abounded in various types of shows involving, in particular, singing, dancing and athletic competitions. To wit, the walls of an ancient tomb in Etruria feature paintings of musicians, sporting events and viewers seated on wooden benches. It seems reasonable to conclude, then, that close contact with this civilization stimulated the Romans’

There is some evidence that the Romans were first exposed to public entertainments not from the Greeks who had colonized southern Italy but the Etruscans to the north. In the sixth and fifth centuries BCE, Etruscan culture abounded in various types of shows involving, in particular, singing, dancing and athletic competitions. To wit, the walls of an ancient tomb in Etruria feature paintings of musicians, sporting events and viewers seated on wooden benches. It seems reasonable to conclude, then, that close contact with this civilization stimulated the Romans’

love of the same early in their history. That their later festivals often featured entertainments such as circuses, horse racing, boxing and wrestling shows how deeply ingrained Etruscan habits were in the Roman character.

Further evidence of this connection lies in several words imported from Etruscan into

Further evidence of this connection lies in several words imported from Etruscan into

Latin: histrio from Etruscan ister meaning

“performer”—it gives us “histrionics”—and

persona from Etruscan phersu meaning “mask,

masked dancer,” the forebear of the English words “person” and “personality.” Thus, borrowings like histrio and persona fit well into a general picture of Etruscan cultural hegemony in early Rome. At the same time, however, there are far more terms in Latin relating to drama which derive from Greek than Etruscan, compelling proof that later Greek influence

on Roman theatre won out over anything the Romans experienced in their early evolution. All in all, the extent of the Etruscans’ impact on early Roman theatre is hard to gauge because it took place so close to the prehistoric period when the Romans were still a very small and insignificant tribe.

The evolution of aboriginal Roman drama is no less difficult to reconstruct, especially since no dramatic script from the period survives. Later Romans during the early Empire (around the first century CE) were as curious as we are about the origins of their drama and investigated the history of performance in primordial Rome, evidently with little more profit than we do. Their theories are often incomplete and contradictory, leaving the impression that even by the first century BCE clear and compelling evidence no longer existed about the nature of early Roman theatre.

For example, classical Latin authors like Horace and Livy posit the origin of Roman drama in performances at country festivals, harvests and weddings. This is exactly what anyone would guess in the absence of hard data—the comparison to Aristotle’s supposition about tragedy and dithyramb is obvious—and to substantiate their claims, they mention various types

For example, classical Latin authors like Horace and Livy posit the origin of Roman drama in performances at country festivals, harvests and weddings. This is exactly what anyone would guess in the absence of hard data—the comparison to Aristotle’s supposition about tragedy and dithyramb is obvious—and to substantiate their claims, they mention various types

of early Roman entertainment, such as Fescennine verses, an apparent reference to Fescennium, a town in southern Etruria. Though no early Fescennine verses are preserved, we are told they involved improvised performances by rustic clowns who deployed a variety of different poetic meters, mocked individuals, used obscenities and spoke in alternation.

When it is all added up, the similarity to early Greek theatre, especially

Old Comedy, is both transparent and telling, which makes this information appear suspect. It looks like an attempt by later Romans to invent some sort of “birth” for their theatre and, in the absence of real evidence, a scenario has been constructed for the advent of this art in early Rome, a historical fiction that parallels the rise of drama in Greece. Moreover, when other sources claim the content of Fescennine verses at one point got so out of hand it had to be controlled by law, a situation resembling closely the transition from Old to Middle Greek

Comedy—remember Platonius’ comment that it was not possible “to ridicule anyone openly, when those who were ridiculed would sue poets in court”— it only heightens the impression that all this may be merely legend borrowed from the Greeks to fill a historical void.

More concrete data are found in other sources, especially archaeological data. There existed in Italy around the time of the early Republic (500-250 BCE) a particular type of tragic parody known as hilarotragodia

(“funny tragedy”) or phlyax plays (“gossip-plays,” pl. phlyaces), or so some sources say. One author’s name is, in fact, recorded—Rhinthon of Syracuse (Sicily)—along with several play titles which, if nothing else, lends this genre greater historical credibility than Fescennine verses.

To these phlyaces scholars have tied a series of vases found in southern Italy which depict farcical scenes from drama, especially mythological burlesque. While this association has not gone unchallenged—other scholars claim that the South Italian vases depict productions of Old Comedy, particularly Aristophanes, where many Greeks lived—these artifacts give clear and visible proof that some sort of comic performance was playing to an Italian, if not Latin-speaking, public in the fourth century BCE. But “Latin-speaking” is essential to the formation of Roman drama, because language is essential to theatre.

To these phlyaces scholars have tied a series of vases found in southern Italy which depict farcical scenes from drama, especially mythological burlesque. While this association has not gone unchallenged—other scholars claim that the South Italian vases depict productions of Old Comedy, particularly Aristophanes, where many Greeks lived—these artifacts give clear and visible proof that some sort of comic performance was playing to an Italian, if not Latin-speaking, public in the fourth century BCE. But “Latin-speaking” is essential to the formation of Roman drama, because language is essential to theatre.

Other evidence suggests that the Etruscans continued to play an important role in Roman life well after their fabled expulsion from Rome in 510 BCE. For instance, in 364 BCE when Rome was threatened by a plague, the Romans reportedly called in Etruscan dancers to appease the gods. Later in 264 BCE—that is, exactly one century later which casts serious doubt on the reliability of the dating—the Romans imported gladiators into their city from Etruria, apparently beginning their long love affair with faux-combat spectacles.

More immediately pertinent to theatre history was, however, the presence andinfluence of the Oscans, a people who lived southeast of Rome. Having overpopulated for some reason in the 300’s BCE and spreading southwest, the Oscans overran the Greek settlements near Naples, which brought them into contact with Rome, on the southern end of the Roman frontier. Shortly thereafter an “Oscan” form of drama is said to have arisen in Rome.

Named Atellan farce (in Latin, Atellana [pl. Atellanae]) after the Oscan town of Atella, this type of comedy featured the “crazy” people who lived in Atella, a place where things were purported to happen backwards, at least by Roman standards—much modern ethnic humor, such as “Pollack jokes,” works on the same principle—and

Named Atellan farce (in Latin, Atellana [pl. Atellanae]) after the Oscan town of Atella, this type of comedy featured the “crazy” people who lived in Atella, a place where things were purported to happen backwards, at least by Roman standards—much modern ethnic humor, such as “Pollack jokes,” works on the same principle—and

while no Atellan farce survives from antiquity, what little of its content we comprehend makes it fascinating, especially because it seems to have shared features with other genres of comedy. For instance, it had a repeating cast of characters, like those in Greek New Comedy but broad caricatures of the sort seen in Old Comedy. We even know some of these characters’ names and their comic types. Maccus, for instance, is a clown, Bucco a stupid braggart, Dossenus a glutton, and Pappus a foolish old man.

But if Atellan farce resembles anything in theatre history, it is no form of ancient drama but commedia dell’arte of the modern age, a type of comedy which arose in late Renaissance Italy and achieved widespread popularity across Europe. In particular, the plot structures and the nature and demeanor of certain characters are remarkably similar. For instance, the physical resemblance of Dossenus from Atellan farce and Pulcinella from commedia dell’arte, both with large, hooked noses and bowed posture, is especially striking.

But if Atellan farce resembles anything in theatre history, it is no form of ancient drama but commedia dell’arte of the modern age, a type of comedy which arose in late Renaissance Italy and achieved widespread popularity across Europe. In particular, the plot structures and the nature and demeanor of certain characters are remarkably similar. For instance, the physical resemblance of Dossenus from Atellan farce and Pulcinella from commedia dell’arte, both with large, hooked noses and bowed posture, is especially striking.

How such a connection arose between these two genres, so removed from each other in time, is difficult to imagine. Was there a later Roman comic tradition which spanned the entire Middle Ages and carried these comic characters across nearly two millennia with remarkable continuity? If so, why is there no clear evidence of this in the historical record? Or do certain types of comedy and comic characterization have such enduring appeal in this part of the world that they will surface again and again, in spite of changes in the cultural climate? It is a question of diffusion versus independent origin—another lumper-splitter dilemma!—where no credible answer is possible in the absence of better evidence.

Still, the success of Atellan Farce in early Rome is indisputable. It took nothing less than Greek-style drama, the fabulae palliatae—that is, “pallium-wearing” plays or dramas in which the characters wear Greek attire—to steal center stage from Atellanae. In other words, only something as compelling as Latin adaptations of Greek comedies

with all their sophisticated plots and characters could lure the Roman audience away from Atellan farce, and then but briefly when seen from the larger perspective of history, for the fabulae palliatae reigned only from 240 BCE to around 120 BCE, little over a century which is a relatively short life span for a theatrical genre. Both before and after this age of literary drama, the Roman public favored native types of comic theatre.

After the fall of the palliatae in the early decades of the first century BCE, Atellan farce rose again to prominence, especially in the hands of two pre-eminent dramatists, Novius and Pomponius. These contemporaries of Sulla, who is said have composed Atellanae himself, wrote “literary”

Atellan farces, if such a thing is imaginable. At present, it is impossible

to gauge their work because none of it survives. Nevertheless, though such a thing as high-brow Atellan farce may be difficult for us to conceive—especially when there are titles like Sargeant Maccus, Maccus Girl,

and The Brothers Macci—the data make it clear that there were, in fact, erudite Atellan farces. The preservation of quotations from Atellanae written in this age leave no doubt about that.

After a generation or so, Atellan farce again faded from general interest,

only to be revived once more at the height of the Pax Romana. During the reign of Domitian (81-96 CE) and later that of Hadrian (117-138 CE), Atellanae appeared again, this time filled with spectacle, as most forms of entertainment were in that day. Following that, Atellan farce died out forever, unless it is the distant forebear of commedia dell’arte which arose well over a millennium later.

Such was the theatre in ancient Rome before the rise of Hellenism and the importation of Greek drama. Broad comedy, it appears, predominated along with music and boisterous stage action, but none of these features can be termed original, or even distinctive, to Roman culture. The impressions of other civilizations—in particular, Etruscan, Oscan and Greek colonial—are already clearly visible in the early Romans’ tastes in entertainment. Thus, the gates of Rome were wide open for other imports, and the most enduring, if not the longest-lived, was poised to make its mark, the drama of classical and post-classical Greece.

III. Roman Theatre

No permanent theatre structure stood in the city of Rome until 55 BCE. Before that, many wooden theatres had risen and subsequently come down in quick succession. This stands in marked contrast to the rest of the Roman world where there were numerous permanent arenas, amphitheatres, stadia and playhouses constructed of stone and concrete, but none inside the city of Rome itself.

No permanent theatre structure stood in the city of Rome until 55 BCE. Before that, many wooden theatres had risen and subsequently come down in quick succession. This stands in marked contrast to the rest of the Roman world where there were numerous permanent arenas, amphitheatres, stadia and playhouses constructed of stone and concrete, but none inside the city of Rome itself.

The typically conservative and tradition-minded Romans of Republican times were suspicious of theatre’s corrupting influence—or was it its anesthetizing esthetic?—a danger all the darker in the shadow of a permanent theatre, and their apprehension would not prove unwarranted. Theatre, as it turned out, was one of the major weapons used by the emperors of Rome to appease, placate and distract the mob and thus maintain a firm grip on the state. Ages ago, Pisistratus had shown the way: tyrants must control the media.

A. Roman Theatre Buildings

Given the absence of any evidence for a permanent structure in which to house drama within the city of Rome up to 55 BCE, historians face a very complicated task in reconstructing the course of early Roman theatre. Worse yet, most play texts

Given the absence of any evidence for a permanent structure in which to house drama within the city of Rome up to 55 BCE, historians face a very complicated task in reconstructing the course of early Roman theatre. Worse yet, most play texts

date to more than a century earlier so that the physical and literary evidence is severely disconnected. In such a situation, we have little choice but to assume that Imperial theatre buildings resembled their Republican predecessors.

If not, it is impossible to ground our understanding of Roman theatre history in primary evidence.

Sad to say, common sense dictates otherwise. Temporary theatres, as all Republican ones were, must have been variable in style: built, no doubt, for special occasions in accordance with changing tastes and the specific venue of performance, and thereafter readily demolished. In such a situation, conformity to any predictable

Sad to say, common sense dictates otherwise. Temporary theatres, as all Republican ones were, must have been variable in style: built, no doubt, for special occasions in accordance with changing tastes and the specific venue of performance, and thereafter readily demolished. In such a situation, conformity to any predictable

or set pattern, much less general uniformity of disposition, seems unlikely,

no more than modern parade floats can be expected to exhibit a strict regularity in their construction.

But modern parade floats do exhibit regularity in some respects—the

expectations of viewers and the physical constraints of the art form limit their designers’ creativity—and so it’s not altogether baseless to try to bridg the gap between the preserved texts and the remains of Roman theatres. At the same time, a special caution is called for because of the difficulties and ambiguities inherent in this vexing situation. All the alarms necessary when one treads into speculation must be raised to their highest levels of alert.

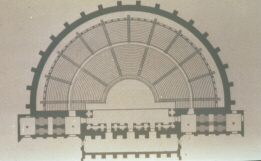

Most extant Roman theatres share certain features. Like Greek acting spaces, they

Most extant Roman theatres share certain features. Like Greek acting spaces, they

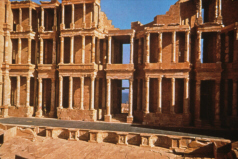

tend to have a roofed house called the scaena (the Latin translation of skene; pl. scaenae) at the back of the stage. The scaenae frons (“the face of the scaena“), the front wall of the scaena building, was at times immense—in some theatres as high as three stories!—and at least one surviving theatre has a scaena with stairs back stage for the actors to climb to the upper levels where there must have been a balcony of sorts on which they could perform.

On the ground level, Roman scaenae usually included three doors, the center one often magnificently ornate and well disposed to grand entrances. The façade

On the ground level, Roman scaenae usually included three doors, the center one often magnificently ornate and well disposed to grand entrances. The façade

of many scaenae was recessed, presumably to permit the illusion of eavesdropping. The stage itself, called the pulpitum, included versurae (“wings”), each with an entrance.

Thus, the Roman playwright had as many as five different ways for his characters to enter the stage, comparable to the three doors and two parodoi available to later Greek dramatists. Because no known early Latin drama calls for so many different entrances, the Republican theatre probably had fewer, which does not inspire confidence in associating early dramatic scripts with later imperial edifices. But without better evidence we have no other option but to keep trying to link stones and Latin.

While the Roman theatre had an orchestra below and in front of the pulpitum, it was not regularly used by the performers but served as

While the Roman theatre had an orchestra below and in front of the pulpitum, it was not regularly used by the performers but served as

a seating area for dignitaries. Since the chorus had ceased to be a force in the theatre long before the dawn of literary drama in Rome—had the cost of the chorus become at last prohibitive?—there were no longer choristers who needed room to dance, not in drama at least. It is always possible other types of entertainment called for using the orchestra as a performance space, so we cannot say with certainty it was always used for seating.

Except for the dignitaries seated in the orchestra, the viewers sat in a large round auditorium called the cavea (“hollow”). In accordance with Roman custom, the seating there was segregated into social classes, sometimes gender, too. Early on, these seats were made of wood—only

later did stone seating come into fashion—much the way Greek theatres

evolved. But unlike their Greek counterparts, Roman theatres were not necessarily built into hillsides, rather in open, public spaces, usually in well-populated areas, such as city centers, where a great number of people had ready access to the entertainments presented there.

These high-rise urban theatres were made possible through the Romans’ invention and widespread use of concrete which allowed the construction of multi-level structures independent of local topography. Indeed, some of the Romans’ more ingenious applications of the concrete arch and vault are to be found in their enormous theatres and amphitheatres, the seating capacities of which far exceeded their Greek equivalents. The Colosseum, for example, in downtown Rome could house more than fifty thousand spectators, three times what the Theatre

of Dionysus in Athens held. No wonder, then, Roman dignitaries wanted to sit in the orchestra where such a large slice of the public could watch them as they watched the play—it is hard to imagine better publicity—so

by its very station in the heart of the city Roman theatre evolved into a regular feature of civic life in the Roman Empire. Depending on one’s political sentiments, that was or was not a good thing.

All in all, the nature and uses of theatre during the preceding age, the Republic, is a matter of debate. How acting spaces were arranged, how

long they were used before being torn down and the extent to which they were adapted for particular productions is lost history which will probably never to be recovered and leaves behind many important questions. Were they, for instance, flimsy structures rebuilt for every change of play? One historian warns that “we should avoid any tendency to equate ‘temporary’ with ‘crude’ and ‘unsophisticated’.” True, but the exact nature of that sophistication is what lies at the core of

the issue, and that is a tantalizing mystery.

What is certain is that outdoor theatres not constructed of stone would require at least some degree of rebuilding, if for no other reason than

simple wear-and-tear. And because during this age theatre was also a burgeoning enterprise in Rome, it seems all the more likely that the structures themselves underwent constant refurbishment. So, with Roman Republican theatre apparently in continual flux, the stages of its evolution, even the larger ones, lie beyond our grasp.

B. Roman Theatre and Drama

Though clouded, our view of early Roman theatre buildings is not, however, entirely obscured. As called for in the dramas which have been

preserved, the staging itself hints at certain features which must have been present in Republican theatre. For instance, there are relatively few props necessary in producing any early Roman drama and all but no application of scenery to plot, which argues for minimal sets and stage decor. Moreover, that the dramatic texts invariably dictate when to bring props on and off the stage argues that there was no curtain or the like whereby the stage could be set or cleared out of the audience’s sight.

Furthermore, when the Romans began adapting Greek drama, they naturally carried over with it those features peculiar to Greek theatre, particularly post-classical or Hellenistic practices. For instance, as in Menandrean comedy, the Roman comic playwrights Plautus and Terence often envisioned the stage as depicting a city street and the entrances as doors to private homes or public shrines. The wing exits frequently represented the way to town and the harbor, or to the market

and the country, with some notable variations called for in particular plays.

Although it is unclear how realistic these depictions were meant to be envisioned in terms of scenery and set pieces, it is notable that the plays themselves often carefully lay out in their language all extraordinary features of the landscape. That argues that the scene was not represented on stage, rather that the audience relied on the spoken word to imagine the setting. On much the same sort of minimal stage and relying on the power of language in much the same way, Shakespeare produced his dramas, to considerable effect.

But one feature of the early Roman stage seems to have been actually visible and tangible and, more important, historical. Characters in Roman Comedy sometimes

But one feature of the early Roman stage seems to have been actually visible and tangible and, more important, historical. Characters in Roman Comedy sometimes

use—and sometimes abuse—an altar during the course

of a play. At the end of Plautus’ Mostellaria (“The Haunted House”), for example, the rascally slave Tranio flees to an altar as a refuge from his enraged master Theopropides who is threatening to beat him. There, the altar functions as a sort of asylum saving the slave from punishment and, given the high emotions of the scene, we must assume it was a real, not imaginary structure on the stage.

Other evidence supports this assumption. That most Roman comedies were presented in the context of a funeral or religious festival of some sort argues for the presence of an actual altar in the general environs. How the Roman priesthood felt about the employment of the altar for comical purposes is another thought-provoking but unanswerable question about theatre in this age.

C. Producers, Directors and Actors

With little evidence for realistic set design or ample props, the scripts

of Roman Comedy seem to suggest that there was little expense incurred in Republican theatrical productions. But all other evidence speaks to the contrary. As early as 186 BCE, the Roman Senate imposed measures on producers to curb their spending on ludi (“games, plays”), by which it is always possible that the senators did not mean the types of Roman Comedy preserved today but some other sort of entertainment. Nevertheless, ludi must refer to something presented on the stage and the fabulae palliatae cannot be ruled out.

Moreover, expensive spectacles were a way for an ambitious Roman politician to win over poor voters and thus gain high office. This, in turn, led to elected officials extorting provinces in an attempt to pay the debts incurred from mounting the exorbitant games they had previously lavished on the public. Thus, the Senate’s legislation attempting to limit theatre-related expenditures may not be so much an attempt to rein in theatre itself but to counteract the consequences of such extravagance. There is all but no evidence that it achieved that aim.

For a host of different reasons, Roman greed bled many provinces dry over the course of the late Republic. Historical data show that, far from being curbed, theatrical productions continued to escalate in both expense and grandeur. In 99 BCE, for instance, one Claudius Pulcher displayed a memorable scaenae frons that had been elaborately painted.

Again, in 70 BCE awnings (vela) were added above the cavea of a Roman theatre to protect viewers from the elements. Marcus Aemilius Scaurus

produced a three-tiered scaenae frons in 58 BCE made of marble, glass

and gilded wood. Shortly thereafter, Gaius Curio built back-to-back hemispherical theatres that could be rotated so as to form an amphitheatre. Excess was, clearly, intrinsic in Roman theatre.

But ingenuity and adaptability were also hallmarks of Italian stagecraft. Unfortunately, what plays, or even what types of plays, were being performed in these architectural and engineering marvels—if they were built for drama at all—is unknown, only that the attraction to the Romans in these theatres was their “special effects,” not their capacity to realize a thought-provoking script. That much at least is clear, as one modern scholar notes:

Theatrical activity was intimately connected with three interlocking facets of Roman life: worship of Gods, the

honouring of the dead, and individual self-glorification, or, put another way, with religious ceremonial, eulogy of the family and vote-winning. All three aspects tended to stimulate and encourage extravagant display and excessive expenditure, and what evidence we have suggests that such display and expenditure were regular features of theatrical shows from a very early period.

It will make sense, then, that acting in Rome was the domain of professionals, almost from the outset. While there is some evidence that amateurs performed in early Atellan farces, the performance of plays in Rome was left largely to specialists, at least some of whom were slaves. These indentured thespians oftentraveled in a troupe called a grex (literally, “a flock,” i.e. of sheep), with a leader who was called a dominus

(“master”). The choice of words clearly shows the Romans’ general

contempt for performers, evidenced also in the insult hurled at Mark Antony that his friends were actors. Still, some Roman stars of the stage were widely known and well-respected, a few even belonging to the middle class.

Several important questions surround actors and the nature of performance in Rome. One is whether or not they wore masks on stage. While there is no direct evidence for their use in Roman Comedy, there is some evidence to the contrary. A passage from Terence’s Phormio, in which a character’s facial expressions is described as changing, appears to make a compelling case for the absence of masks, until, of course, one realizes that the description may be a sophisticated metatheatrical gag playing on the inability of the actor to change his facial expression.

Several important questions surround actors and the nature of performance in Rome. One is whether or not they wore masks on stage. While there is no direct evidence for their use in Roman Comedy, there is some evidence to the contrary. A passage from Terence’s Phormio, in which a character’s facial expressions is described as changing, appears to make a compelling case for the absence of masks, until, of course, one realizes that the description may be a sophisticated metatheatrical gag playing on the inability of the actor to change his facial expression.

The real question, however, centers not on the use but the application of masks on the Roman stage. In Greek comedy they are essential in role-changing because they allow performers, in accordance with the three-actor rule, to play multiple characters within a single drama. But there is clearly no such restriction in Roman Comedy where as many as six speaking characters—though that many is very rare—appear on stage at once. Nevertheless, if Roman actors in palliatae played multiple roles, it

argues in favor of the deployment of masks which would greatly enhance the dramatic illusion.

Certainly, nothing in the comedies themselves absolutely forbids their use. Masks are, furthermore, useful in helping men play women’s roles—just as on the Greek stage, there were no female performers in Roman Comedy—and aid also in distinguishing character-types for the sizeable crowds playwrights like Plautus are said to have drawn. Given all this and the tradition of mask-wearing in Atellan farce, logic dictates that the Roman stage did indeed call for masks in performance, though admittedly the evidence is far from conclusive.

D. Conclusion: A Roman Theatre (at last!)

The turning point in Roman theatre construction came in the last days of the Republic, when the first permanent theatre was finally built in the city of Rome. None other than Pompey himself instigated and oversaw its construction, in the days of his greatest glory after he had triumphed more than once. For a man who had spent many years outside Rome, the

absence of an impressive, permanent theatre in his home town, the imminent capital of the ancient world, must have seemed appalling.

So, while Caesar was off conquering Gaul, an unwitting Senate approved plans for what was later called the Theatre of Pompey but looked at first to them like a temple dedicated to Venus, the Roman goddess of love.

When conservative senators and Pompey’s political adversaries realized, too late, that there was a theatre attached to the temple—what had appeared to be steps leading up to the temple turned out, in fact, to be the seats of a theatre!—their protests were too late and under the guise of a temple a stone theatre arose at last in downtown Rome.

A generation later, Rome housed two more, as a great age of theatre construction all over the Mediterranean world dawned. The next three centuries, the first of the modern age, witnessed in more ways than one the erection of many commanding Roman theatres. It is these we see and tread today amidst the ruins of the grandeurthat once was Rome.

| Terms, Places, People and Things to Know | |

| Native Italian Drama Literary Drama Popular Entertainment Histrio Persona Fescennine Verses Fescennium Hilarotragodia/Phlyax Plays (Phlyaces) Rhinthon of Syracuse Oscans Atella Atellan Farce (Atellenae) Maccus Commedia dell’Arte |

Fabulae Palliatae Novius Pomponius Scaena Scaenae Frons Pulpitum Versurae Orchestra Cavea Concrete Altar Grex Dominus Theatre of Pompey |

This section is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivative Works 3.0 United States License. Copyright Damen, 2012.