2 The Nature of Entrepreneurship

Adapted by Stephen Skripak with Ron Poff

The Nature of Entrepreneurship

If we look a little more closely at the definition of entrepreneurship, we can identify three characteristics of entrepreneurial activity:[1]

- Innovation. Entrepreneurship generally means offering a new product, applying a new technique or technology, opening a new market, or developing a new form of organization for the purpose of producing or enhancing a product.

- Running a business. A business, as we saw in Chapter 1 “The Foundations of Business,” combines resources to produce goods or services. Entrepreneurship means setting up a business to make a profit.

- Risk taking. The term risk means that the outcome of the entrepreneurial venture can’t be known. Entrepreneurs, therefore, are always working under a certain degree of uncertainty, and they can’t know the outcomes of many of the decisions that they have to make. Consequently, many of the steps they take are motivated mainly by their confidence in the innovation and in their understanding of the business environment in which they’re operating.

It is easy to recognize these characteristics in the entrepreneurial experience of the Jurmains. They certainly had an innovative idea. But was it a good business idea? In a practical sense, a “good” business idea has to become something more than just an idea. If, like the Jurmains, you’re interested in generating income from your idea, you’ll probably need to turn it into a product—something that you can market because it satisfies a need. If you want to develop a product, you’ll need some kind of organization to coordinate the resources necessary to make it a reality (in other words, a business). Risk enters the equation when you make the decision to start up a business and when you commit yourself to managing it.

A Few Things to Know about Going into Business for Yourself

Mark Zuckerberg founded Facebook while a student at Harvard. By age 27 he built up a personal wealth of $13.5 billion. By age 31, his net worth was $37.5 billion.

So what about you? Do you ever wonder what it would be like to start your own business? You might even turn into a “serial entrepreneur” like Marcia Kilgore.[2] After high school, she moved from Canada to New York City to attend Columbia University. But when her financial aid was delayed, Marcia abandoned her plans to attend college and took a job as a personal trainer (a natural occupation for a former bodybuilder and middleweight title holder). But things got boring in the summer when her wealthy clients left the city for the Hamptons. To keep busy, she took a skin care course at a Manhattan cosmetology institute. As a teenager, she was self-conscious about her complexion and wanted to know how to treat it herself. She learned how to give facials and work with natural remedies. She started giving facials to her fitness clients who were thrilled with the results. As demand for her services exploded, she started her first business—Bliss Spa—and picked up celebrity clients, including Madonna, Oprah Winfrey, and Jennifer Lopez. The business went international, and she sold it for more than $30 million.[3]

But the story doesn’t end here; she launched two more companies: Soap and Glory, a supplier of affordable beauty products sold at Target, and FitFlops, which sells sandals that tone and tighten your leg muscles as you walk. Oprah loves Kilgore’s sandals and plugged them on her show.[4] You can’t get a better endorsement than that. Kilgore never did finish college, but when asked if she would follow the same path again, she said, “If I had to decide what to do all over again, I would make the same choices…I found by accident what I’m good at, and I’m glad I did.”

So, a few questions to consider if you want to go into business for yourself:

- How do I find a problem to solve and know it is an opportunity worth pursuing?

- How do I come up with a business idea?

- Should I build a business from scratch, buy an existing business, or invest in a franchise?

- What steps are involved in developing a business plan?

- Where could I find help in getting my business started?

- How can I increase the likelihood that I’ll succeed?

In this chapter, we’ll provide some answers to questions like these.

Why Start Your Own Business?

What sort of characteristics distinguishes those who start businesses from those who don’t? Or, more to the point, why do some people actually follow through on the desire to start up their own businesses? The most common reasons for starting a business are the following:

- To be your own boss

- To accommodate a desired lifestyle

- To achieve financial independence

- To enjoy creative freedom

- To use your skills and knowledge

The Small Business Administration (SBA) points out, though, that these are likely to be advantages only “for the right person.” How do you know if you’re one of the “right people”? The SBA suggests that you assess your strengths and weaknesses by asking yourself a few relevant questions:[5]

- Am I a self-starter? You’ll need to develop and follow through on your ideas.

- How well do I get along with different personalities? Strong working relationships with a variety of people are crucial.

- How good am I at making decisions? Especially under pressure…..

- Do I have the physical and emotional stamina? Expect six or seven work days of about twelve hours every week.

- How well do I plan and organize? Poor planning is the culprit in most business failures.

- How will my business affect my family? Family members need to know what to expect: long hours and, at least initially, a more modest standard of living.

Before we discuss why businesses fail we should consider why a huge number of business ideas never even make it to the grand opening. One business analyst cites four reservations (or fears) that prevent people from starting businesses:[6]

- Money. Without cash, you can’t get very far. What to do: line up initial financing early or at least have done enough research to have a plan to raise money.

- Security. A lot of people don’t want to sacrifice the steady income that comes with the nine-to-five job. What to do: don’t give up your day job. Run the business part-time or connect with someone to help run your business—a “co-founder.”

- Competition. A lot of people don’t know how to distinguish their business ideas from similar ideas. What to do: figure out how to do something cheaper, faster, or better.

- Lack of ideas. Some people simply don’t know what sort of business they want to get into. What to do: find out what trends are successful. Turn a hobby into a business. Think about a franchise. Find a solution to something that annoys you—entrepreneurs call this a “pain point” —and try to turn it into a business.

If you’re interested in going into business for yourself, try to regard such drawbacks as mere obstacles to be overcome by a combination of planning, talking to potential customers, and creative thinking.

Sources of Early-Stage Financing

As noted above, many businesses fail, or never get started, due to a lack of funds. But where can an entrepreneur raise money to start a business? Many first-time entrepreneurs are financed by friends and family, at least in the very early stages. Others may borrow through their personal credit cards, though quite often, high interest rates make this approach unattractive or too expensive for the new business to afford.

An entrepreneur with a great idea may win funding through a pitch competition; localities and state agencies understand that economic growth depends on successful new businesses, and so they will often conduct such competitions in the hopes of attracting them.

Crowd funding has become more common as a means of raising capital. An entrepreneur using this approach would typically utilize a crowd-funding platform like Kickstarter to attract investors. The entrepreneur might offer tokens of appreciation in exchange for funds, or perhaps might offer an ownership stake for a substantial enough investment.

Some entrepreneurs receive funding from angel investors, affluent investors who provide capital to start-ups in exchange for an ownership position in the company. Many angels are successful entrepreneurs themselves and invest not only to make money, but also to help other aspiring business owners to succeed.

Venture capital firms also invest in start-up companies, although usually at a somewhat later stage and in larger dollar amounts than would be typical of angel investors. Like angels, venture firms also take an ownership position in the company. They tend to have a higher expectation of making a return on their money than do angel investors. However, venture capitalists expect you have some paying customers to demonstrate the value your start-up brings to the marketplace.

What Industries Are Small Businesses In?

If you want to start a new business, you probably should avoid certain types of businesses. You’d have a hard time, for example, setting up a new company to make automobiles or aluminum, because you’d have to make tremendous investments in property, plant, and equipment, and raise an enormous amount of capital to pay your workforce. These large, up-front investments present barriers to entry.

Fortunately, plenty of opportunities are still available. Many types of businesses require reasonable initial investments, and not surprisingly, these are the ones that usually present attractive small business opportunities.

Industries by Sector

Let’s define an industry as a group of companies that compete with one another to sell similar products. We’ll focus on the relationship between a small business and the industry in which it operates, dividing businesses into two broad types of industries, or sectors: the goods-producing sector and the service-producing sector.

- The goods-producing sector includes all businesses that produce tangible goods. Generally speaking, companies in this sector are involved in manufacturing, construction, and agriculture.

- The service-producing sector includes all businesses that provide services but don’t make tangible goods. They may be involved in retail and wholesale trade, transportation, finance, entertainment, recreation, accommodations, food service, and any number of other ventures.

About 20 percent of small businesses in the United States are concentrated in the goods-producing sector. The remaining 80 percent are in the service sector.[7] The high concentration of small businesses in the service-producing sector reflects the makeup of the overall US economy. Over the past 50 years, the service-producing sector has been growing at an impressive rate. In 1960, for example, the goods-producing sector accounted for 38 percent of GDP, the service-producing sector for 62 percent. By 2015, the balance had shifted dramatically, with the goods-producing sector accounting for only about 21 percent of GDP.[8]

Goods-Producing Sector

The largest areas of the goods-producing sector are construction and manufacturing. Construction businesses are often started by skilled workers, such as electricians, painters, plumbers, and home builders, and they generally work on local projects. Though manufacturing is primarily the domain of large businesses, there are exceptions. BTIO/Realityworks, for example, is a manufacturing enterprise (components come from Ohio and China, and assembly is done in Wisconsin).

How about making something out of trash? Daniel Blake never followed his mother’s advice at dinner when she told him to eat everything on his plate. When he served as a missionary in Puerto Rico, Aruba, Bonaire, and Curacao after his first year in college, he noticed that the families he stayed with didn’t either. But they didn’t throw their uneaten food into the trash. Instead they put it on a compost pile and used the mulch to nourish their vegetable gardens and fruit trees. While eating at an all-you-can-eat breakfast buffet back home at Brigham Young University, Blake was amazed to see volumes of uneaten food in the trash. This triggered an idea: why not turn the trash into money? Two years later, he was running his company—EcoScraps—collecting 40 tons of food scraps a day from 75 grocers and turning it into high-quality potting soil that he sells online and to nurseries. His profit has reach almost half a million dollars on sales of $1.5 million.[9]

Service-Producing Sector

Many small businesses in this sector are retailers—they buy goods from other firms and sell them to consumers, in stores, by phone, through direct mailings, or over the Internet. In fact, entrepreneurs are turning increasingly to the Internet as a venue for start-up ventures. Take Tony Roeder, for example, who had a fascination with the red Radio Flyer wagons that many of today’s adults had owned as children. In 1998, he started an online store through Yahoo! to sell red wagons from his home. In three years, he turned his online store into a million-dollar business.[10]

Other small business owners in this sector are wholesalers—they sell products to businesses that buy them for resale or for company use. A local bakery, for example, is acting as a wholesaler when it sells desserts to a restaurant, which then resells them to its customers. A small business that buys flowers from a local grower (the manufacturer) and resells them to a retail store is another example of a wholesaler.

A high proportion of small businesses in this sector provide professional, business, or personal services. Doctors and dentists are part of the service industry, as are insurance agents, accountants, and lawyers. So are businesses that provide personal services, such as dry cleaning and hairdressing.

David Marcks, for example, entered the service industry about 14 years ago when he learned that his border collie enjoyed chasing geese at the golf course where he worked. While geese are lovely to look at, they can make a mess of tees, fairways, and greens. That’s where Marcks’ company, Geese Police, comes in: Marcks employs specially trained dogs to chase the geese away. He now has 27 trucks, 32 border collies, and five offices. Golf courses account for only about 5 percent of his business, as his dogs now patrol corporate parks and playgrounds as well.[11]

Starting a Business

Ownership Options

As we’ve already seen, you can become a small business owner in one of three ways— by starting a new business, buying an existing one, or obtaining a franchise. Let’s look more closely at the advantages and disadvantages of each option.

Starting from Scratch

The most common—and the riskiest—option is starting from scratch. This approach lets you start with a clean slate and allows you to build the business the way you want. You select the goods or services that you’re going to offer, secure your location, and hire your employees, and then it’s up to you to develop your customer base and build your reputation. This was the path taken by Andres Mason who figured out how to inject hysteria into the process of bargain hunting on the Web. The result is an overnight success story called Groupon.[12] Here is how Groupon (a blend of the words “group” and “coupon”) works: A daily email is sent to 6.5 million people in 70 cities across the United States offering a deeply discounted deal to buy something or to do something in their city. If the person receiving the email likes the deal, he or she commits to buying it. But, here’s the catch, if not enough people sign up for the deal, it is cancelled. Groupon makes money by keeping half of the revenue from the deal. The company offering the product or service gets exposure. But stay tuned: the “daily deals website isn’t just unprofitable—it’s bleeding hundreds of millions of dollars.”[13] As with all start-ups cash is always a challenge.

Buying an Existing Business

If you decide to buy an existing business, some things will be easier. You’ll already have a proven product, current customers, active suppliers, a known location, and trained employees. You’ll also find it much easier to predict the business’s future success.

There are, of course, a few bumps in this road to business ownership. First, it’s hard to determine how much you should pay for a business. You can easily determine how much things like buildings and equipment are worth, but how much should you pay for the fact that the business already has steady customers?

In addition, a business, like a used car, might have performance problems that you can’t detect without a test drive (an option, unfortunately, that you don’t get when you’re buying a business). Perhaps the current owners have disappointed customers; maybe the location isn’t as good as it used to be. You might inherit employees that you wouldn’t have hired yourself. Careful study called due diligence is necessary before going down this road.

Getting a Franchise

Lastly, you can buy a franchise. A franchiser (the company that sells the franchise) grants the franchisee (the buyer—you) the right to use a brand name and to sell its goods or services. Franchises market products in a variety of industries, including food, retail, hotels, travel, real estate, business services, cleaning services, and even weight-loss centers and wedding services. Figure 7.7 lists the top 10 franchises according to Entrepreneur magazine for 2015 and 2016.

| Ranking | 2015 | 2016 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hampton by Hilton | Jimmy John’s | McDonald’s | Dunkin’ |

| 2 | Anytime Fitness | Hampton by Hilton | Dunkin’ | Taco Bell |

| 3 | Subway | Supercuts | Sonic Drive-In | McDonald’s |

| 4 | Jack in the Box | Servpro | Taco Bell | Sonic Drive-In |

| 5 | Supercuts | Subway | The UPS Store | The UPS Store |

| 6 | Jimmy John’s | McDonald’s | Culver’s | ACE Hardware |

| 7 | Servpro | 7-Eleven | Planet Fitness | Planet Fitness |

| 8 | Denny’s | Dunkin’ | Great Clips | Jersey Mike’s Subs |

| 9 | Pizza Hut | Denny’s | Jersey Mike’s Subs | Culver’s |

| 10 | 7-Eleven | Anytime Fitness | 7-Eleven Inc. | Pizza Hut LLC |

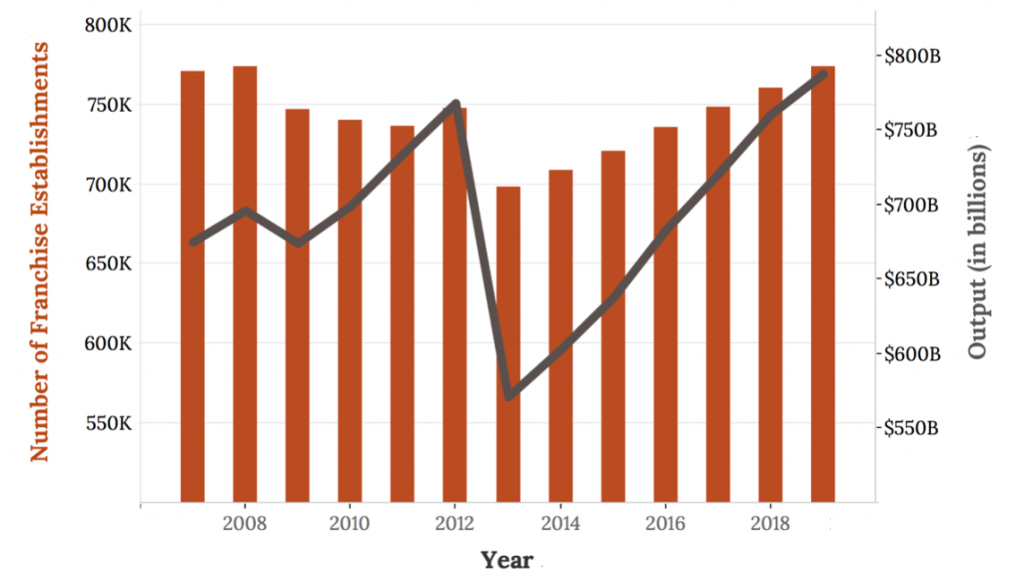

As you can see from Figure 7.8 on the next page, the popularity of franchising has been growing quickly since 2011. Although the economic downturn decreased the number of franchises between 2008-11, note that the overall value of franchise outputs steadily increased. A new franchise outlet opens once every eight minutes in the United States, where one in ten businesses is now a franchise. Franchises employ eight million people (13 percent of the workforce) and account for 17 percent of all sales in the US ($1.3 trillion).[14]

In addition to the right to use a company’s brand name and sell its products, the franchisee gets help in picking a location, starting and operating the business, and benefits from advertising done by the franchiser. Essentially, the franchisee buys into a ready-to-go business model that has proven successful elsewhere, also getting other ongoing support from the franchiser, which has a vested interest in her success.

Coming with so many advantages, franchises can be very expensive. KFC franchises, for example, require a total investment of $1.3 million to $2.5 million each. This fee includes the cost of the property, equipment, training, start-up costs, and the franchise fee—a one-time charge for the right to operate as a KFC outlet. McDonald’s is in the same price range ($1 million to $2.3 million). SUBWAY sandwich shops offer a more affordable alternative, with expected total investment ranging from $116,000 to $263,000.[15]

In addition to your initial investment, you’ll have to pay two other fees on a monthly basis—a royalty fee (typically from 3 to 12 percent of sales) for continued support from the franchiser and the right to keep using the company’s trade name, plus an advertising fee to cover your share of national and regional advertising. You’ll also be expected to buy your products from the franchiser.[16]

But there are disadvantages. The cost of obtaining and running a franchise can be high, and you have to play by the franchiser’s rules, even when you disagree with them. The franchiser maintains a great deal of control over its franchisees. For example, if you own a fast-food franchise, the franchise agreement will likely dictate the food and beverages you can sell; the methods used to store, prepare, and serve the food; and the prices you’ll charge. In addition, the agreement will dictate what the premises will look like and how they’ll be maintained. As with any business venture, you need to do your homework before investing in a franchise.

Launching a Business from the Inside

When someone mentions “entrepreneurship,” many people equate the term to “start up,” but entrepreneurial activity can also come from within established firms. However, it’s often the case that the entrepreneurial spirit is not fully unleashed until an independent entity is formed around a venture.

That’s exactly what happened in the case of Qualtrax, a company located in Blacksburg, Virginia.[17] The company was spawned from a need for customers of CCS, Inc. to become compliant with the requirements of the International Standards Organization. CCS (now known as Foxguard Solutions) employees developed a software tool to simplify ISO compliance audits, and the auditors were so impressed that they suggested marketing the tool more broadly. Over a period of nearly 20 years, the business grew to 10 dedicated employees, but Foxguard did not invest heavily in the software because the product was essentially a sideline business. Qualtrax shared sales and marketing resources with other business lines, so its growth was not necessarily a focal point for the company.

In 2011, CCS management appointed Amy Ankrum, an executive in their marketing department, to lead the Qualtrax business line with a simple mission in mind—determining whether Qualtrax could be scaled up or should be scaled down. Having the feeling that there was more to the business than had been achieved to date, Amy added Ryan Hagan as engineering manager for the software. Hagan quickly moved Qualtrax to an agile style of development, allowing for 5-6 new releases a year when annual releases had previously been the norm. This approach was much more responsive to customer needs, and in a business that depends on recurring revenue, it led to increased customer retention, which improved to over 95 percent each year. Revenue growth rates went up double digits.

In 2015, Qualtrax took its biggest leap of faith, moving out of Foxguard headquarters and becoming a separate legal entity. Ankrum located the offices near the campus of Virginia Tech, allowing the company to attract top-notch developers. The new location also allowed the company to take on its own culture—it’s more like a start-up company now than it was 23 years ago when it started! Employees enjoy flexible hours, short walks to downtown lunches, and a brightly-lit, open, and collaborative space with the company values painted right on the walls.

The move to a separate entity also allowed the company to attract new investor funding which will be used to push the company into new markets, such as the utility industry. Much of the new investor group is local and made up of former executives with significant experience in Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) and Business-to-Business (B2B) relationships. These execs will offer expertise beyond what Qualtrax had in-house, and all involved share the objective of increasing job growth in the region.

Asked what was different before and after Qualtrax began its rapid growth, Ankrum said, “It takes focus for any business to reach its full potential.” Since becoming its own company, Qualtrax has certainly enhanced that focus, and the new funding will allow them to offer ownership options to its now 26 employees. Qualtrax now dominates in quality and compliance software for a number of industries, including forensic crime labs. Thanks to the foresight of management, the company’s best days most certainly lie ahead.

Image Credits: Figure 7.1: Anthony Quintano (2018). “Mark Zuckerberg F8 2018 Keynote.” CC BY 2.0. Retrieved from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mark_Zuckerberg_F8_2018_Keynote.jpg

Figure 7.3: Macrotrends. “Amazon annual revenue growth (2008-2019).” Data retrieved from: https://www.macrotrends.net/stocks/charts/AMZN/amazon/revenue; Amazon.com, Inc. (2006). “Amazon.com – Logo.” Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. Retrieved from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Amazon.com-Logo.svg

Figure 7.4 U.S. Census Bureau (2016). “Annual Survey of Entrepreneurs, Characteristics of Business Owners.” Retrieved from: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/ase/data/tables.html.

Figure 7.5: U.S. Census Bureau. “Number of Small Business Establishments by Industry.” Data Retrieved from: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2017/econ/susb/2017-susb-annual.html

Figure 7.6: John Anderson (2006). “Starbucks Street Musician.” CC BY-SA 2.0. Retrieved from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Original_Starbucks#/media/File:Starbucks_street_musician.jpg

Figure 7.7: Entrepreneur. “Entrepreneur’s Top Franchises (2020).” Data Retrieved from: https://www.entrepreneur.com/franchise500/2020

Figure 7.8: Statista. “The Growth of Franchising in the U.S.” Output Data Retrieved from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/190318/economic-output-of-the-us-franchise-sector/; Franchise Data Retrieved from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/190313/estimated-number-of-us-franchise-establishments-since-2007/

Figure 7.9: Stephen Skipak (2017). “Amy Ankrum at the Qualtrax Headquarters in Blacksburg, Virginia.”

- Adapted from Marc J. Dollinger (2003). Entrepreneurship: Strategies and Resources, 3rd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. pp. 5–7. ↵

- Encyclopedia of World Biography (2006). “Marcia Kilgore: Entrepreneur and spa founder.” Retrieved from: http://www.notablebiographies.com/newsmakers2/2006-Ei-La/Kilgore-Marcia.html ↵

- Jessica Bruder (2010). “The Rise Of The Serial Entrepreneur.” Forbes. Retrieved from: http://www.forbes.com/2010/08/12/serial-entrepreneur-start-up-business-forbes-woman-entrepreneurs-management.html ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- U.S. Small Business Administration (2016). “Is Entrepreneurship For You?” Retrieved from: https://www.sba.gov/starting-business/how-start-business/entrepreneurship-you ↵

- Shari Waters (2016). “Top Four Reasons People Don’t Start a Business.” The Balance Small Businesses. Retrieved from: http://retail.about.com/od/startingaretailbusiness/tp/overcome_fears.htm ↵

- U.S. Census Bureau (2012). “Estimates of Business Ownership by Gender, Ethnicity, Race, and Veteran Status: 2012.” Retrieved from: http://www.census.gov/library/publications/2012/econ/2012-sbo.html#par_reference_25 ↵

- Central Intelligence Agency (2016). “World Factbook.” Retrieved from: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2012.html ↵

- Ecoscraps (2016). “Our Story." Retrieved from: http://ecoscraps.com/pages/our-story ↵

- Isabel Isidro (2003). “How to Succeed Online with a Niche Business: Case of RedWagons.com.” PowerHomeBiz.com. Retrieved from: http://www.powerhomebiz.com/online-business/success-online-business/succeed-online-niche-business-case-redwagons-com.htm ↵

- Isabel Isidro (2001). “Geese Police: A Real-Life Home Business Success Story.” PowerHomeBiz.com. Retrieved from: http://www.powerhomebiz.com/working-from-home/success/geese-police-real-life-home-business-success-story.htm ↵

- Christopher Steiner (2010). “Meet the Fastest Growing Company Ever.” Forbes. Retrieved from: http://www.forbes.com/forbes/2010/0830/entrepreneurs-groupon-facebook-twitter-next-web-phenom.html ↵

- The Week (2011). “Groupon's 'Startling' Reversal of Fortune.” Yahoo.com. Retrieved from: https://www.yahoo.com/news/groupons-startling-reversal-fortune-172800802.html ↵

- U.S. Census Bureau (2008). “2007 Economic Census: Franchise Statistics.” Retrieved from: https://www.census.gov/econ/census/pdf/franchise_flyer.pdf ↵

- Hayley Peterson (2014). “Here's How Much It Costs To Open Different Fast Food Franchises In The US.” Business Insider. Retrieved from: http://www.businessinsider.com/cost-of-fast-food-franchise-2014-11 ↵

- Michael Seid and Kay Marie Ainsley (2002). “Franchise Fee—Made Simple.” Entrepreneur. Retrieved from: https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/51174 ↵

- Stephen Skripak (2017, February 22). Interview with Amy Ankrum. ↵