11 Chapter 11: Modernism

Learning Objectives ~ Chapter 11 “Modernism”

- Discuss the rise of Modernism

- Explore the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche and discuss his innovative philosophy about good and evil

- Examine how the impulse to “make it new” sent the visual arts onto a path of immense creativity

“It’s ugly, but is it art?”

― Pictures from an Institution

“Traditionally, artists suffered for their art, now it’s the audience.”

―

Modernism is both a philosophical movement and an art movement that, along with cultural trends and changes, arose from wide-scale and far-reaching transformations in Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Among the factors that shaped modernism were the development of modern industrialism and the rapid growth of cities, followed then by reactions to the horrors of World War I. Modernism also rejected the certainty of Enlightenment thinking, although many modernists also rejected religious belief. Instead, modernists explored secular morality. That is, a set of moral and ethical standards not affixed to historical periods, tradition or religious institutions.

Modernism, in general, includes the activities and creations of those who felt the traditional forms of art, architecture, literature, religious faith, philosophy, social organization, activities of daily life, and sciences were becoming ill-fitted to their tasks and outdated in the new economic, social, and political environment of an emerging fully industrialized world. The poet Ezra Pound‘s 1934 injunction to “Make it new!” was the touchstone of the movement’s approach towards what it saw as the now obsolete culture of the past.

A notable characteristic of modernism is self-consciousness and irony concerning literary and social traditions, which often led to experiments with form, along with the use of techniques that drew attention to the processes and materials used in creating a painting, poem, building and other works of art. Modernism explicitly rejected the ideology of realism, which focused on idea that sense perception, and our cognition of such, is what provides us with knowledge of things “as they really are.” But there seems to be a built-in contradiction there. Reality is supposed to be an absolute, independent of anything. Is that not what “truth” is?

Modernists explored the individual experience. They felt that to truly liberate the mind and spirit, one had to unshackle themselves from the bonds of history, tradition, social and religious institutions. It was a Brave New World, indeed.

****************************************************************

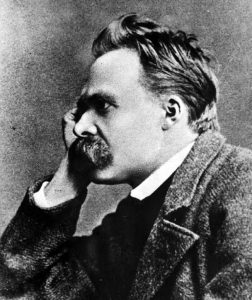

Friedrich Nietzsche ~ Madman and Prophet

Friedrich Nietzsche (15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher, composer, poet, cultural critic, and scholar of Latin and Greek whose work has exerted a profound influence on modern intellectual history. He began his career as a classical philologist before turning to philosophy. He became the youngest ever to hold the Chair of Classical Philology at the University of Basel, Switzerland, in 1869 at the age of 24. Nietzsche resigned in 1879 due to health problems that plagued him most of his life; he completed much of his core writing in the following decade. In 1889, at age 44, he suffered a collapse and afterward a complete loss of his mental faculties. He lived his remaining years in the care of his mother until her death in 1897 and then with his sister Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche. Nietzsche died in 1900.

Nietzsche’s writing spans philosophical polemics, poetry, cultural criticism, and fiction while displaying a fondness for aphorism and irony. Prominent elements of his philosophy include his radical critique of truth in favor of perspectivism; his genealogical critique of religion and Christian morality and his related theory of master–slave morality; his aesthetic affirmation of existence in response to the “death of God” and the profound crisis of nihilism; his notion of the Apollonian and Dionysian; and his characterization of the human subject as the expression of competing wills, collectively understood as the will to power. He also developed influential concepts such as the Übermensch and the doctrine of eternal return. In his later work, he became increasingly preoccupied with the creative powers of the individual to overcome social, cultural and moral contexts in pursuit of new values and aesthetic health. His body of work touched a wide range of topics, including art, philology, history, religion, tragedy, culture, and science, and drew early inspiration from figures such as philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, composer Richard Wagner, and writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

After his death, his sister Elisabeth became the curator and editor of Nietzsche’s manuscripts, reworking his unpublished writings to fit her own German nationalist ideology while often contradicting or obfuscating Nietzsche’s stated opinions, which were explicitly opposed to antisemitism and nationalism. Through her published editions, Nietzsche’s work became associated with fascism and Nazism; 20th century scholars contested this interpretation of his work and corrected editions of his writings were soon made available. Nietzsche’s thought enjoyed renewed popularity in the 1960s and his ideas have since had a profound impact on 20th and early-21st century thinkers across philosophy—especially in schools of continental philosophy such as existentialism, postmodernism and post-structuralism—as well as art, literature, psychology, politics and popular culture. Source

Reading Nietzsche’s work is not easy, let alone understanding it. However, to Nietzsche, struggle in all forms is not only beneficial but necessary to be fully actualized as a human being. Physical, intellectual, moral… all these aspects of one’s life must involve not just dealing with adversity but seeking it out. After all, Nietzsche’s best known phrase, “what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger,” is a credo to apply in all facets of one’s life.

On this note, here is Nietzsche articulating the idea that true intellectual prowess is the for the few who are willing to do the work:

“If this writing be obscure to any individual, and jar on his ears, I do not think that it is necessarily I who am to blame. It is clear enough, on the hypothesis which I presuppose, namely, that the reader has first read my previous writings and has not grudged them a certain amount of trouble: it is not, indeed, a simple matter to get really at their essence. Take, for instance, my Zarathustra; I allow no one to pass muster as knowing that book, unless every single word therein has at some time wrought in him a profound wound, and at some time exercised on him a profound enchantment: then and not till then can he enjoy the privilege of participating reverently in the halcyon element, from which that work is born, in its sunny brilliance, its distance, its spaciousness, its certainty.” (from section 8 in the Preface to The Genealogy of Morals)

Nietzsche, as stated previously, wrote with a sort of poetic punch! A metaphor-rich, parabolic stream of consciousness! One of the challenges of reading Nietzsche is that he does not present philosophical argument in the usual way, the reasoned-discourse style of tradition. But then, that disregard for tradition and its fashions of proper method of inquiry is one of the hallmarks of MODERNISM.

Please read the following excerpts from The Genealogy of Morals:

From the Preface, read sections 1, 2, and 3. Then, from “The First Essay: Good and Bad”, read sections 1, 2, and 3.

Consider these questions in your reading:

- What is the tone in which Nietzsche addresses his reader?

- Is it clear what Nietzsche is proposing to examine in this text?

- To Nietzsche, what is the problem with concepts like “good and bad” or “good and evil”?

- What is the value of morality that is not affixed to religious belief?

**************************************************************

Modern Art: Impressionism, Fauvism, Expressionism

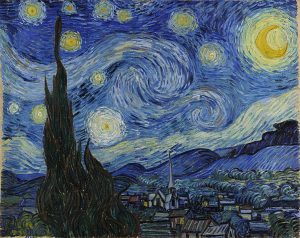

Vincent Van Gogh. Starry Night. Source

Modern art includes artistic work produced during the period extending roughly from the 1860s to the 1970s, and denotes the styles and philosophy of the art produced during that era. The term is usually associated with art in which the traditions of the past have been thrown aside in a spirit of experimentation. Modern artists experimented with new ways of seeing and with fresh ideas about the nature of materials and functions of art. A tendency away from the narrative, which was characteristic for the traditional arts, toward abstraction is characteristic of much modern art. More recent artistic production is often called contemporary art or postmodern art.

Modern art begins with the heritage of painters like Vincent van Gogh, Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, Georges Seurat and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec all of whom were essential for the development of modern art. At the beginning of the 20th century Henri Matisse and several other young artists including the pre-cubists Georges Braque, André Derain, Raoul Dufy, Jean Metzinger and Maurice de Vlaminck revolutionized the Paris art world with “wild”, multi-colored, expressive landscapes and figure paintings that the critics called Fauvism. Matisse’s two versions of The Dance signified a key point in his career and in the development of modern painting.[3] It reflected Matisse’s incipient fascination with primitive art: the intense warm color of the figures against the cool blue-green background and the rhythmical succession of the dancing nudes convey the feelings of emotional liberation and hedonism.

Initially influenced by Toulouse-Lautrec, Gauguin and other late-19th-century innovators, Pablo Picasso made his first cubist paintings based on Cézanne’s idea that all depiction of nature can be reduced to three solids: cube, sphere and cone. With the painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), Picasso dramatically created a new and radical picture depicting a raw and primitive brothel scene with five prostitutes, violently painted women, reminiscent of African tribal masks and his own new Cubist inventions. Analytic cubism was jointly developed by Picasso and Georges Braque, exemplified by Violin and Candlestick, Paris, from about 1908 through 1912. Analytic cubism, the first clear manifestation of cubism, was followed by Synthetic cubism, practiced by Braque, Picasso, Fernand Léger, Juan Gris, Albert Gleizes, Marcel Duchamp and several other artists into the 1920s. Synthetic cubism is characterized by the introduction of different textures, surfaces, collage elements, papier collé and a large variety of merged subject matter.

The notion of modern art is closely related to modernism.

Please read this series of short and informative essays on Impressionism:

The Modernist attack on established notions of art and aesthetics continued through the last quarter of the 19th century and well into the 20th century. Please read these short essays and view the paintings of Fauvism and Expressionism:

Please focus on the following learning outcomes to guide your reading:

- How are these three art styles similar? In what ways can you detect the Modernist approach?

- How did these art styles get their names? These stories/anecdotes give great insight into the style and the artists who thrived in that style.

- If you were to select one work from each style that best represents the style AND modernism, what would they be?

***************************************************************

Modern Dance

Modern dance is often considered to have emerged as a rejection of, or rebellion against, classical ballet. Socioeconomic and cultural factors also contributed to its development. In the late 19th century, dance artists such as Isadora Duncan, Maud Allan, and Loie Fuller were pioneering new forms and practices in what is now called aesthetic or free dance for performance. These dancers disregarded ballet’s strict movement vocabulary, the particular, limited set of movements that were considered proper to ballet, and stopped wearing corsets and pointe shoes in the search for greater freedom of movement.

Here is a piece choreographed by Isadora Duncan. Please note the quality of movement and how it differs from classical ballet of chapter 4.

Isadora Duncan once wrote, “The dancer’s body is simply the luminous manifestation of the soul.” To Duncan, dance was pure joy and it follows that it should be individual, expressive and pleasurable. It should be natural, a delightful melding of human movement and music. Duncan believed that classical ballet was far too restrictive and damaging to the body. No turn out, toe shoes and academic movement for Isadora!

Modern dance was and continues to be very experimental. One rather fantastical example of this, one that had the audience horrified and appalled, was Vaslav Nijinsky’s L’apres-midi d’un faune (The Afternoon of a Faun). In 1912, Nijinsky brought together the poem by Stephane Mallarme and music by Debussy into a work that would truly pave the way for extraordinary new visions for the world of dance.

The poem by Stephane Mallarme is about a faun, a mythological half-human, half-goat, that wakes in a forest after having a dream. At least he thinks it was a dream. Or maybe it wasn’t. His dream then comes to life and he enters into this world of imagination and fantasy.

From “L’apres midi d’un faune” (1876):

These nymphs I would make last.

So rare

Their rose lightness arches in the air,

Torpid with tufted sleep.

I loved: a dream?

My doubt, thick with ancient night, it seems

Drawn up in subtle branches, ah, that leave

The true trees, proof that I alone have heaved

For triumph in the roses’ ideal folds.

Look, perhaps …

are the women which you told

Ones your mythic wishing-sense has schemed?

Faun, the illusion, when the fountains teemed,

Fled her cold, blue eyes – she untouched.

But the second, full of sighs, say you how much

Like a hot day’s breath she thrilled your fleece?

If not? Through this still, slack-flesh peace

That would, if heated, choke the fresh morning,

No stream goes but that my flute is pouring,

Over assent-sprayed groves; the solo breeze

– Agile from my double pipe – it is eased:

To shower down the sound in arid rain

And then, on the unrippled world-plane,

Be breath – visible, serene, man-sent –

Of inspiration, lodged in firmament. ….

The poem, the music of Claude Debussy and the choreography of Nijinsky: