7 Chapter 7: The Enlightenment!

Learning Objectives ~ Chapter 7 “The Enlightenment!”

- Compare and contrast absolutist and enlightenment values

- Describe the “claims of reason” by various Enlightenment thinkers and consider the potential ‘blind spots’

- Discuss the impact of European Enlightenment values on the American revolution

- Consider the impact of Diderot’s Encyclopedia by discussing how access to information impacts our lives today

“Every man has a property in his own person. This nobody has a right to, but himself.” ~ John Locke

“If the abstract rights of man will bear discussion, those of women, by parity of reasoning, will not shrink from the same test.” ~ Mary Wollstonecraft

The span of history known widely as the Enlightenment, refers to a period in western Europe hallmarked by intellectual and philosophical inquiry. Also known as the “Age of Reason,” the period between 1650 to 1800, the Enlightenment is often regaled on somewhat superficial terms simply because of the weight and associations of the term itself. The term “enlightenment” suggests that all of a sudden, someone flipped the light switch on throughout all of Europe. The scales fell from people’s eyes and all of a sudden REASON led the way toward greater things. Freedom, equality, independence and sovereignty! These are grand ideas, indeed, and they were at the forefront of intellectual treatises of this period. Some saw clearly the connection between education and a successful democracy. Some were willing to test the limits of the notion of Natural Law, which was often used as the rationale for revolution. Some, like early feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, were fearless in pointing out what she saw as the hypocritical stances of men praising the primacy of reason and its relation to freedom. In Of Civil Government (1690), John Locke demonstrated the intellectual current of the time claiming that God gave man the world and reason is the faculty man uses to put himself in the advantage. Man has certain natural rights, over his body, his labor, and the products of that labor. As stated in the quote that begins this chapter, every man has sovereignty over his own body, and in essence, over his own life. In A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), Mary Wollstonecraft pointed out that the rights and freedoms so cavalierly hailed during her time, simply did not carry over to include women. The “Rights of Man” seem to exclude others… and thus, true freedom has not really arrived.

The Enlightenment is known for certain advancements in science, government and society. Literacy rates in some western European countries grew impressively. Education was once considered a privilege for only the upper class. However, during the 17th and 18th centuries, “education, literacy and learning” were gradually provided to “rich and poor alike”. The literacy rate in Europe from the 17th century to the 18th century grew significantly. The definition of the term “literacy” in the 17th and 18th centuries is different from our current definition of literacy. Historians measured the literacy rate during the 17th and 18th century centuries by people’s ability to sign their names. However, this method of determining literacy did not reflect people’s ability to read. This affected the women’s apparent literacy rate prior to the Age of Enlightenment mainly because, while most women living between the Dark Ages and the Age of Enlightenment could not write or sign their names, many could read, at least to some extent.

The rate of illiteracy decreased more rapidly in more populated areas and areas where there was mixture of religious schools. The literacy rate in England in the 1640s was around 30 percent for males, rising to 60 percent in the mid-18th century. In France, the rate of literacy in 1686-90 was around 29 percent for men and 14 percent for women, it increased to 48 percent for men and 27 percent for women. The increase in literacy rate was more likely due, at least in part to religious influence, since most of the schools and colleges were organized by clergy, missionaries, or other religious organizations. The reason which motivated religions to help to increase the literacy rate among the general public was because the bible was being printed in more languages and literacy was thought to be the key to understanding the word of God. “By 1714 the proportion of women able to read had risen, very approximately, to 25%, and it rose again to 40% by 1750. This increase was part of a general trend, fostered by the Reformation emphasis on reading the scripture and by the demand for literacy in an increasingly mercantile society. The group most affected was the growing professional and commercial class, and writing and arithmetic schools emerged to provide the training their sons required”. The impact of the Reformation on literacy was, of course, far more dramatic in Protestant areas. Therefore, literacy rates in predominantly Protestant Northern Europe rose much more quickly than those in predominately Catholic southern Europe. The Jesuits, who were the product of the Catholic Reformation (Counter Reformation) contributed moderately to increased literacy in Catholic regions.

Newtonian science, natural “rights,” a literate middle class with upward aspirations, educational reform …. These components of the Enlightenment are fascinating on their own. But it is even more interesting to study how these ideas meshed and became the groundwork for our modern age.

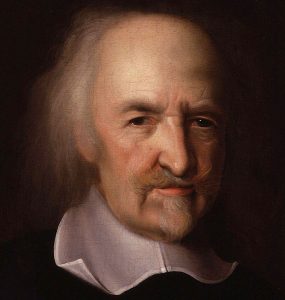

Thomas Hobbes and John Locke ~ Two Perspectives on Human Nature and Reason

Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) was an English philosopher, considered to be one of the founders of modern political philosophy. Hobbes is best known for his 1651 book Leviathan, which expounded an influential formulation of social contract theory. The social contract theory, which examined and promoted the idea of a contract, written and agreed upon by both the ruler and the ruled, is the only way to safe gain the long term productivity and strength of a nation. Hobbes insisted that the sovereign of a nation plays a key role in this contract, or he even uses the word “covenant” which has a certain association to the idea of the sacred. The true aim in government should be toward the Commonwealth. In Chapter 17: Of the Causes, Generation, and Definition of a Commonwealth, he wrote:

“For the Lawes of Nature (as Justice, Equity, Modesty, Mercy, and (in summe) Doing To Others, As Wee Would Be Done To,) if themselves, without the terrour of some Power, to cause them to be observed, are contrary to our naturall Passions, that carry us to Partiality, Pride, Revenge, and the like. And Covenants, without the Sword, are but Words, and of no strength to secure a man at all. Therefore notwithstanding the Lawes of Nature, (which every one hath then kept, when he has the will to keep them, when he can do it safely,) if there be no Power erected, or not great enough for our security; every man will and may lawfully rely on his own strength and art, for caution against all other men. And in all places, where men have lived by small Families, to robbe and spoyle one another, has been a Trade, and so farre from being reputed against the Law of Nature, that the greater spoyles they gained, the greater was their honour; and men observed no other Lawes therein, but the Lawes of Honour; …”

Locke insisted that the sovereign, as a figurehead, represents authority and the will and means to keep the “natural passions” of man in check. A covenant, a sacred commitment toward the common good, the Commonwealth, needs some element of leadership and example to ensure the maintenance of law and order.

The online Gutenburg edition of The Leviathan is linked here. Primary sources like this are so valuable. Though Locke’s writing style may be challenging as it is lodged in the rhetorical style of the age, it is interesting reading nonetheless. There are two sections to explore: Part II, Chapter 17: Of the Causes, Generation, and Definition of a Commonwealth and Chapter 30: Of the Office of the Sovereign Representative.

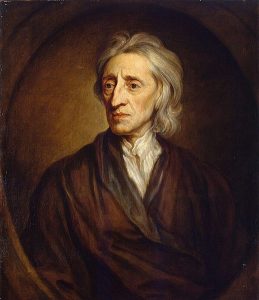

John Locke (born August 29, 1632, in Wrington, Somerset, England—died October 28, 1704, High Laver, Essex), was an English philosopher whose works lie at the foundation of modern philosophical empiricism and political liberalism. He was an inspirer of both the European Enlightenment and the Constitution of the United States. His philosophical thinking was close to that of the founders of modern science, especially Robert Boyle, Sir Isaac Newton, and other members of the Royal Society. His political thought was grounded in the notion of a social contract between citizens and in the importance of toleration, especially in matters of religion. Much of what he advocated in the realm of politics was accepted in England after the Glorious Revolution of 1688–89 and in the United States after the country’s declaration of independence in 1776. More on his life and works can be found here.

Though in agreement with Hobbes about the concept of a social contract, Locke refuted Hobbes point of view that man is by nature aggressive and self-serving. He insisted that man is born tabula rasa, a “blank slate.” Man is not born with any traits whatsoever. It is environmental influences that make a man’s character. (And yes, do please note the prevalence of the word “man” and its underpinnings.) It is society that makes the man. If this is true, and rational, then it only follows that society as a whole benefits through a social infrastructure that gives individuals access to education and opportunity. In Of Civil Government (1690), Locke puts forth so many ideas that modern democratic principles are grounded in:

“TO understand political power right, and derive it from its original, we must consider, what state all men are naturally in, and that is, a state of perfect freedom to order their actions, and dispose of their possessions and persons, as they think fit, within the bounds of the law of nature, without asking leave, or depending upon the will of any other man.

A state also of equality, wherein all the power and jurisdiction is reciprocal, no one having more than another; there being nothing more evident, than that creatures of the same species and rank, promiscuously born to all the same advantages of nature, and the use of the same faculties, should also be equal one amongst another without subordination or subjection, unless the lord and master of them all should, by any manifest declaration of his will, set one above another, and confer on him, by an evident and clear appointment, an undoubted right to dominion and sovereignty.”

The social contract concept is one of mutual respect and mutual advantage. A government for the people, by the people, where everyone, even the leader, follows the rules.

Here is the link for the primary text on Project Gutenburg: Of Civil Government. Please scroll to the following sections: Chapter II: Of the State of Nature, Chapter V: Of Property, Chapter VIII: The Beginnings of Political Societies, and Chapter XVIII: Of Tyranny.

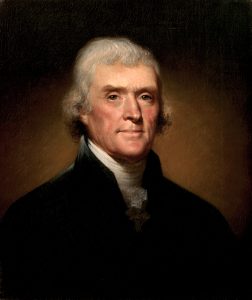

Thomas Jefferson and Enlightenment Values

John Locke’s work traveled widely and was read and discussed throughout Europe and North America. His views on religious tolerance, social and educational reform, the limited power of the sovereign, and the importance of individual and political freedom, were embraced by American politician, writer, architect, Thomas Jefferson. Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826), was was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He previously served as the second vice president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. The principal author of the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson was a proponent of democracy, republicanism, and individual rights, motivating American colonists to break from the Kingdom of Great Britain and form a new nation; he produced formative documents and decisions at both the state and national level.

Although Jefferson is regarded as a leading spokesman for democracy and republicanism in the era of the Enlightenment, some modern scholarship has been critical of Jefferson, finding a contradiction between his ownership and trading of many slaves that worked his plantations, and his famous declaration that “all men are created equal”. Although the matter remains a subject of debate, most historians believe that Jefferson had a sexual relationship with his slave Sally Hemings, a mixed-race woman who was a half-sister to his late wife and that he fathered at least one of her children. Presidential scholars and historians generally praise Jefferson’s public achievements, including his advocacy of religious freedom and tolerance in Virginia. To read a full overview of Jefferson’s life and career, click here.

It is clear, when reading the introduction of the Constitution, the Declaration of Independence (1776), that there are traces of European Enlightenment ideas and ideals and that they are woven together in this treatise that speaks of Natural Law, Natural Rights, social contract and the RIGHT to revolution:

“When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.—That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed,— That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.— Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States.”

Read the entire Declaration: here.

What About Women?~ Mary Wollstonecraft’s Vindication

Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-1797) was an English writer, philosopher, and advocate of women’s rights. Until the late 20th century, Wollstonecraft’s life, which encompassed several unconventional personal relationships at the time, received more attention than her writing. Today Wollstonecraft is regarded as one of the founding feminist philosophers, and feminists often cite both her life and her works as important influences.

During her brief career, she wrote novels, treatises, a travel narrative, a history of the French Revolution, a conduct book, and a children’s book. Wollstonecraft is best known for A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), in which she argues that women are not naturally inferior to men, but appear to be only because they lack education. She suggests that both men and women should be treated as rational beings and imagines a social order founded on reason.

The Gutenburg Project, again, gives us this very important primary text. Here is A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Please read the Introduction and Chapter 1. Pay attention to Wollstonecraft’s use of natural law and rights as she gives a testimony for the true reasons behind the commonly held of the time that women are by nature inferior to man. It is clear to Wollstonecraft, in her adherence to Lockean thought, that environment, society and education (or lack of), are the crucial components that contribute to intelligence. Wollstonecraft posits the idea that “the mind has no sex” and that human potential is stymied by societal and governmental inequities as they pertain to women.

The Philosophes and the Rise of the Salon!

In this painting The Salon of Madam Geoffrin, there is a glimpse inside a popular practice of Enlightenment France, of middle to upper class individuals making their homes into places where free-thinkers, poets, artists, philosophers and politicians could gather to discuss “modern” ideas. Madam Geoffrin was a French salon holder who has been referred to as one of the leading female figures in the French Enlightenment. From 1750–1777, Madame Geoffrin played host to many of the most influential Philosophes and Encyclopédistes of her time. Her association with several prominent dignitaries and public figures from across Europe has earned Madame Geoffrin international recognition. Her patronage and dedication to both the philosophical men of letters and talented artists that frequented her house is emblematic of her role as guide and protector. In her salon on the Rue St. Honore, Madame Geoffrin demonstrated qualities of politeness and civility that helped stimulate and regulate intellectual discussion. Her actions as a Parisian salonnière exemplify many of the most important characteristics of Enlightenment sociability.

The ideas and ideals of the Enlightenment were summed up in a massive work, a “monumental literary endeavor,” that was the combined thirty-five volume work of noted contributors. Largely the editorial result of Denis Diderot (1713-1784), it was hailed as the largest collection of philosophical, scientific, historical and humanities-based writings and inquiry. Around 200 individuals contributed a mass of over 72,000 entries on a wide range of subjects.

The Encyclopedie

Enlightenment Themes

In this lecture, I give an overview of key themes. Please watch: