12 Chapter 12: Freud and the “in-between” World

Learning Objectives ~ Chapter 12 “Freud and the ‘in-between’ World”

- Describe Freud’s theory of the tripartite psyche

- Discuss how Freudian psychology inspired artists and writers by looking at selected works

- Consider how Freudian ideas liberated creativity

- Explore the Dadaist perspective

- Consider the connections between Freudian ideas and surrealism

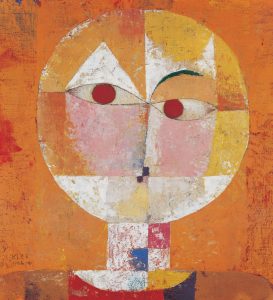

Paul Klee. Senecio. 1922.

“Only children, madmen, and savages truly understand the ‘in-between’ world of spiritual truth.”

~ Paul Klee

In Paul Klee’s painting Senecio (Latin. “Old Man”), we encountered the gaze of a man. Through the use of geometric forms, Klee gives us the impression that his eyebrows are raised in interest, as if he is just as curious about you, the viewer, as you are of him. And yet, he is truly just paint, color and form. But there is something mesmerizing about this portrait. It’s so simple and yet it connects with the viewer in a profound way. The inner psyche of this old man, is it confused or menacing? What are we to make of his piercing gaze?

Paul Klee ( 18 December 1879 – 29 June 1940) was a Swiss-born artist. His highly individual style was influenced by movements in art that included Expressionism, Cubism, and Surrealism. Klee was a natural draftsman who experimented with and eventually deeply explored color theory, writing about it extensively; his lectures Writings on Form and Design Theory (Schriften zur Form und Gestaltungslehre), published in English as the Paul Klee Notebooks, are held to be as important for modern art as Leonardo da Vinci‘s A Treatise on Painting for the Renaissance. He and his colleague, Russian painter Wassily Kandinsky, both taught at the Bauhaus school of art, design and architecture in Germany. His works reflect his dry humor and his sometimes childlike perspective, his personal moods and beliefs, and his musicality. More on Klee’s life and works here.

When writing about his creative process, Klee stated, “Everything vanishes around me, and works are born as if out of the void. Ripe, graphic fruits fall off. My hand has become the obedient instrument of a remote will.” In this quote, Klee describes a stream of consciousness approach. To Klee, the creative impulse is so strong and it arises from deep within him. He is essentially a mere conduit for something that seeks to be born. His rational mind is taking a second place to another consciousness that lies deep within him.

It is a powerful and provocative idea. And it parallels the theories of Sigmund Freud. Perhaps no figure in the western world has been more influential in areas outside of his original discipline, which was psychiatry, than Sigmund Freud. Freudian theory, though largely dismissed today, went on to have immeasurable influence on the arts.

*********************************************************************

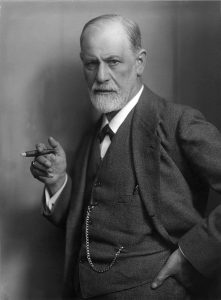

Sigmund Freud. Photo by Max Halberstadt.

Sigmund Freud (6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for treating psychopathology through dialogue between a patient and a psychoanalyst. This method of dialogue resulting in qualitative “evidence” is considered more of a clinical investigation than a scientific approach. However, methodology aside, Freud’s ideas about the psyche, dreams, inhibitions and desire are rather fascinating. His work delved into that “in-between” world which so enthralled Paul Klee.

Freud was born to Jewish parents in the town of Frieberg, in what was part of the Austrian Empire. He qualified as a doctor of medicine in 1881 at the University of Vienna. Upon completing his habilitation in 1885, he was appointed a docent in neuropathology and became an affiliated professor in 1902. Freud lived and worked in Vienna, having set up his clinical practice there in 1886. In 1938, Freud left Austria to escape the Nazis. He died in exile in the United Kingdom in 1939.

In founding psychoanalysis, Freud developed therapeutic techniques such as the use of free association and discovered transference, establishing its central role in the analytic process. Freud’s redefinition of sexuality to include its infantile forms led him to formulate the Oedipus complex as the central tenet of psychoanalytical theory. His analysis of dreams as wish-fulfillments provided him with models for the clinical analysis of symptom formation and the underlying mechanisms of repression. On this basis Freud elaborated his theory of the unconscious and went on to develop a model of psychic structure comprising id, ego and super-ego. Freud postulated the existence of libido, a sexualised energy with which mental processes and structures are invested and which generates erotic attachments, and a death drive, the source of compulsive repetition, hate, aggression and neurotic guilt. In his later works, Freud developed a wide-ranging interpretation and critique of religion and culture. Source.

To understand Freud’s theory of the Tripartite Psyche, read here. As you read pay special attention to Freud’s claim that human beings are largely compelled in their actions through visceral impulses, like appetite and sex. This idea runs counter to the rather lofty and positive belief that grace and innate goodness are what make up the inner life. Freud rejected any religious associations like the idea that human beings are made in the image of God or that they are “born good.” Rather, he believed that childhood experiences are largely responsible for our psychic development.

Freud also insisted that we learn at a very young age to hide or resist our ID impulses. The Superego is comprised of our experiences and socializing effects of society and culture and it acts as a sort of moral monitor. The Ego is a guise we put on, again, largely due to what we have learned gets the results we want! So, there is a built-in falseness, in a sense.

Where do we find the truth about ourselves? Well, in various states of mind/being when the Ego and Superego are less powerful: dreams and/or intoxication!

To get a sense of Freud’s ideas, take a look at the introduction and first chapter in Dream Psychology.

Consider these questions as you read Freud:

- What can the study of the mind reveal that the study of the body cannot?

- Why has the medical world resisted the study of the mind?

- How does Freud explain how shadows of our experience make their way into our dreams?

Freud’s ideas were so provocative in his time. Many were horrified that he so boldly eviscerated Christian ideas. And yet, so very many artists, writers, philosophers saw a light of truth in his ideas. Freudian theory launched a revolution not just in the world of psychology, but in the world of the arts.

********************************************************************

“The Mind” in Literature

The impact of Freudian ideas was vast and it changed the direction of literature in exciting and shocking ways. Freud had a pessimistic view of humanity. His theories disconnected humanity from the idea of an innate, God-given moral compass. His theories also suggested that humans are largely motivated by animal instincts.

What is the human mind? And, as Billie Eilish asks, “when we all fall asleep, where do we go?” 🙂

Influenced by Freudian theories, writers began to explore the psychic life of characters in extraordinarily new ways. Marcel Proust (10 July 1871 – 18 November 1922) was a French novelist, critic, and essayist best known for his monumental novel À la recherche du temps perdu (In Search of Lost Time; earlier rendered as Remembrance of Things Past), published in seven parts between 1913 and 1927. He is considered by critics and writers to be one of the most influential authors of the 20th century.

Begun in 1909, when Proust was 38 years old, À la recherche du temps perdu consists of seven volumes totaling around 3,200 pages (about 4,300 in The Modern Library’s translation) and featuring more than 2,000 characters. Graham Greene called Proust the “greatest novelist of the 20th century”, and W. Somerset Maugham called the novel the “greatest fiction to date”. André Gide was initially not so taken with his work. The first volume was refused by the publisher Gallimard on Gide’s advice. He later wrote to Proust apologizing for his part in the refusal and calling it one of the most serious mistakes of his life.

Proust died before he was able to complete his revision of the drafts and proofs of the final volumes, the last three of which were published posthumously and edited by his brother Robert. The book was translated into English by C. K. Scott Moncrieff, appearing under the title Remembrance of Things Past between 1922 and 1931. Scott Moncrieff translated volumes one through six of the seven volumes, dying before completing the last. This last volume was rendered by other translators at different times. When Scott Moncrieff’s translation was later revised (first by Terence Kilmartin, then by D. J. Enright) the title of the novel was changed to the more literal In Search of Lost Time. source

There are two Freudian techniques that Proust employs in the work: free association and stream of consciousness. In free association, Proust tries to free experience from time, space, and even the mechanics of writing. He is interested in memory, how we hold onto some memories and why. In stream of consciousness, Freud’s technique of allowing the patient the process of following a thought without censure, Proust is able to chase after a memory in a very unique way.

From the first volume of In Search of Lost Time, entitled Swann’s Way, there is a notable scene involving tea and a cookie. Proust writes:

“Many years had elapsed during which nothing of Combray, save what was comprised in the theatre and the drama of my going to bed there, had any existence for me, when one day in winter, as I came home, my mother, seeing that I was cold, offered me some tea, a thing I did not ordinarily take. I declined at first, and then, for no particular reason, changed my mind. She sent out for one of those short, plump little cakes called ‘petites madeleines,’ which look as though they had been moulded in the fluted scallop of a pilgrim’s shell. And soon, mechanically, weary after a dull day with the prospect of a depressing morrow, I raised to my lips a spoonful of the tea in which I had soaked a morsel of the cake. No sooner had the warm liquid, and the crumbs with it, touched my palate than a shudder ran through my whole body, and I stopped, intent upon the extraordinary changes that were taking place. An exquisite pleasure had invaded my senses, but individual, detached, with no suggestion of its origin. And at once the vicissitudes of life had become indifferent to me, its disasters innocuous, its brevity illusory—this new sensation having had on me the effect which love has of filling me with a precious essence; or rather this essence was not in me, it was myself. I had ceased now to feel mediocre, accidental, mortal. Whence could it have come to me, this all-powerful joy? I was conscious that it was connected with the taste of tea and cake, but that it infinitely transcended those savours, could not, indeed, be of the same nature as theirs. Whence did it come? What did it signify? How could I seize upon and define it?”

In this quick episode is a mystery. While having tea, he dips his madeleine into the tea and tastes it. Suddenly, a flood of sensation happens. What is it? What did the taste of the cookie unlock? To what memory is this taste sensation linked and why does it remain in his psyche? As Proust progresses in the book, he uses free association and stream of consciousness techniques almost as if it is HE who is on Freud’s couch, following a thought fearlessly, wherever it leads him. As Proust continues:

“And once I had recognized the taste of the crumb of madeleine soaked in her decoction of lime-flowers which my aunt used to give me (although I did not yet know and must long postpone the discovery of why this memory made me so happy) immediately the old grey house upon the street, where her room was, rose up like the scenery of a theatre to attach itself to the little pavilion, opening on to the garden, which had been built out behind it for my parents (the isolated panel which until that moment had been all that I could see); and with the house the town, from morning to night and in all weathers, the Square where I was sent before luncheon, the streets along which I used to run errands, the country roads we took when it was fine. And just as the Japanese amuse themselves by filling a porcelain bowl with water and steeping in it little crumbs of paper which until then are without character or form, but, the moment they become wet, stretch themselves and bend, take on colour and distinctive shape, become flowers or houses or people, permanent and recognisable, so in that moment all the flowers in our garden and in M. Swann’s park, and the water-lilies on the Vivonne and the good folk of the village and their little dwellings and the parish church and the whole of Combray and of its surroundings, taking their proper shapes and growing solid, sprang into being, town and gardens alike, from my cup of tea.” Swann’s Way

Proust claimed that “the past is hidden somewhere outside the realm, beyond the reach of intellect, in some material object (in the sensation which the material object will give us) which we do not suspect.

Artists like Salvatore Dali were fascinated by things “outside the realm.”

*****************************************************************

Please read this article on dadaism and surrealism, paying special attention to the work of Duchamps and Dali:

Let these questions guide your reading:

- In what way was the Dada Movement and anti-movement?

- What was the Dadaist credo? How was that manifest in Dada art?

- Define surrealism and note how it may have been influenced by Freudian ideas.

- Which work by Dali best represents the mind? 🙂

Frida Kahlo (6 July 1907 – 13 July 1954) was a Mexican painter known for her many portraits, self portraits, and works inspired by the nature and artifacts of Mexico. Inspired by the country’s popular culture, she employed a naïve folk art style to explore questions of identity, postcolonialism, gender, class, and race in Mexican society.[1] Her paintings often had strong autobiographical elements and mixed realism with fantasy. In addition to belonging to the post-revolutionary Mexicayotl movement, which sought to define a Mexican identity, Kahlo has been described as a surrealist or magical realist.

Born to a German father and a mestiza mother, Kahlo spent most of her childhood and adult life at La Casa Azul, her family home in Coyoacán, now publicly accessible as the Frida Kahlo Museum. Although she was disabled by polio as a child, Kahlo had been a promising student headed for medical school until a traffic accident at age eighteen, which caused her lifelong pain and medical problems. During her recovery, she returned to her childhood hobby of art with the idea of becoming an artist.

Her work was influenced greatly by her accident and also the other “great accident of her life,” Diego Rivera. Please read this article on Kahlo, noting how she uses her art to look into her own psyche and feelings: