13 Chapter 13: War and the Arts

Learning Objectives ~ Chapter 13 “War and the Arts”

- Describe the effects of trench warfare on the European literary imagination

- Consider the impact of the Russian Revolution on the arts

- Explore the ways in which artists critiqued life in 1920s Berlin

- Explain the rise of fascism and its impact on the arts

- Outline the reaction of artists to world war

As the 19th century drew to a close, there was a sense of optimism in the air. In fact, the first decade of the 20th century in the west is also known as La Belle Epoque, the beautiful age. However, nationalism had been brooding and building throughout Europe, there were blatant contrasts between the rich and the poor, and as capitalism and industrialism continued to flourish and spread, the outcome was not positive. In fact, many of these factors led Europe and North America into “the war to end all wars.”

In this lecture I give you a quick overview and talk about the role the arts played in patriotic zeal:

Wilfred Owen’s poem Dulce Et Decorum Est is still relevant. Please read it here: Owen

This glimpse of the horror of war was in stark contrast with the tidy and romantic view of the war… and of patriotism. From Smarthistory, here is another synopsis of this period and the artistic responses to it:

***********************************************************

Ironically enough, the “war to end all wars” did not. In fact, hindsight shows us that WWI and the aftershocks and after-effects, set the stage for a century very heavy with war.

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social revolution across the territory of the Russian Empire, commencing with the abolition of the monarchy in 1917, and concluding in 1923 after the Bolshevik establishment of the Soviet Union, including national states of Ukraine, Azebaijan and others, and end of the Civil War.

It began during the First World War, with the February Revolution that was focused in and around Petrograd (now Saint Petersburg), the capital of Russia at that time. The revolution erupted in the context of Russia’s major military losses during the War, which resulted in much of the Russian Army being ready to mutiny. In the chaos, members of the Duma, Russia’s parliament, assumed control of the country, forming the Russian Provisional Government. This was dominated by the interests of large capitalists and the noble aristocracy. The army leadership felt they did not have the means to suppress the revolution, and Emperor Nicholas II abdicated his throne. Grassroots community assemblies called ‘Soviets‘, which were dominated by soldiers and the urban industrial working class, initially permitted the Provisional Government to rule, but insisted on a prerogative to influence the government and control various militias.

A period of dual power ensued, during which the Provisional Government held state power while the national network of Soviets, led by socialists, had the allegiance of the lower classes and, increasingly, the left-leaning urban middle class. During this chaotic period, there were frequent mutinies, protests and strikes. Many socialist political organizations were engaged in daily struggle and vied for influence within the Duma and the Soviets, central among which were the Bolsheviks (“Ones of the Majority”) led by Vladimir Lenin. He campaigned for an immediate end of Russia’s participation in the War, granting land to the peasants, and providing bread to the urban workers. When the Provisional Government chose to continue fighting the war with Germany, the Bolsheviks and other socialist factions exploited the virtually universal disdain towards the war effort as justification to advance the revolution further. The Bolsheviks turned workers’ militias under their control into the Red Guards (later the Red Army), over which they exerted substantial control.[1]

The situation climaxed with the October Revolution in 1917, a Bolshevik-led armed insurrection by workers and soldiers in Petrograd that successfully overthrew the Provisional Government, transferring all its authority to the Soviets. They soon relocated the national capital to Moscow. The Bolsheviks had secured a strong base of support within the Soviets and, as the supreme governing party, established a federal government dedicated to reorganizing the former empire into the world’s first socialist state, to practice Soviet democracy on a national and international scale. Their promise to end Russia’s participation in the First World War was fulfilled when the Bolshevik leaders signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with Germany in March 1918. To further secure the new state, the Bolsheviks established the Cheka, a secret police that functioned as a revolutionary security service to weed out, execute, or punish those considered to be “enemies of the people” in campaigns consciously modeled on those of the French Revolution.

Soon after, civil war erupted among the “Reds” (Bolsheviks), the “Whites” (counter-revolutionaries), the independence movements, and other socialist factions opposed to the Bolsheviks. It continued for several years, during which the Bolsheviks defeated both the Whites and all rival socialists. Victorious, they reconstituted themselves as the Communist Party. They also established Soviet power in the newly independent republics of Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia and Ukraine. They brought these jurisdictions into unification under the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) in 1922. While many notable historical events occurred in Moscow and Petrograd, there were also major changes in cities throughout the state, and among national minorities throughout the empire and in the rural areas, where peasants took over and redistributed land.

In all of this, rich voices arise! The creative spirit is fearless, as exemplified in the life and art of Varvara Stepanova:

Questions to consider:

- In what ways did Stepanova use her art to express patriotism?

- What is photomontage? In what ways can it be effective rhetorically?

- How would you compare/contrast this to Soviet Realism? (This was mentioned in a previous chapter so to remind you, click here Soviet/Socialist Realism)

*****************************************************

And on to World War II:

One of the most profound works of the 20th century is Elie Wiesel’s Night. Wiesel was a Romanian Jew who was shipped along with his family to the concentration camp, Auschwitz. Night is a memoir that recounts his experience. It is also a work in which a character asks, in the midst of unspeakable horror, “Where is God?” How could this happen and what’s more, how could God allow it? In a crisis of faith, a character speaks:

“Because He caused thousands of children to burn in His mass graves? Because He kept six crematoria working day and night, including Sabbath and the Holy Days? Because in His great might, He had created Auschwitz, Birkenau, Buna, and so many other factories of death? How could I say to Him: Blessed be Thou, Almighty, Master of the Universe, who chose us among all nations to be tortured day and night, to watch as our fathers, our mothers, our brothers end up in the furnaces? … But now, I no longer pleaded for anything. I was no longer able to lament. On the contrary, I felt very strong. I was the accuser, God the accused.”

On the afternoon of April 26, 1937, during the Spanish Civil War that pitted the republican forces against the Fascist dictatorship of Francisco Franco, the German Air Force (in cahoots with the Fascist government) dropped bombs on Guernica, a small Basque town in northeast Spain. After reading of this monstrous deed, Pablo Picasso sought to express it visually. This becomes Guernica (1937):

For a better image and explication, see here.

***************************************************

The Communist Revolution in China

The Communist Party of China was founded in 1921, during the May Fourth Movement, which Mao Zedong referred to as the birth of communism in China.[10]

After a period of slow growth and alliance with the Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist Party), the alliance broke down and the Communists fell victim in 1927 to a purge carried out by the Kuomintang under the leadership of Chiang Kai-shek.[11] After 1927, the Communists retreated to the countryside and built up local bases throughout the country and continued to hold them until the Long March. During the Japanese invasion and occupation, the Communists built more secret bases in the Japanese occupied zones and relied on them as headquarters.

Some historians have traced the origins of the 1949 Revolution to sharp inequalities in society. John Peter Roberts, for instance, writes that under the Qing dynasty, high rates of rent, usury and taxes concentrated wealth into the hands of a tiny minority of village chiefs and landlords. He quotes the statistic that “Ten percent of the agricultural population of China possessed as much as two-thirds of the land”.[4] Many of these historians also argue that China was under heavy colonialist pressure by the Western powers and the Japanese and “Century of Humiliation” starting with the Opium Wars and including unequal treaties, the Boxer Rebellion. This group concludes that extreme internal inequality and external aggression led to a rise in nationalism, class consciousness and leftism among vast swaths of the population.[citation needed]

After internal unrest and foreign pressure weakened the Qing state, a revolt among newly modernized army officers led to the Xinhai Revolution, which ended 2,000 years of imperial rule and established the Republic of China.[5] Following the end of World War I and October Revolution in Russia, labor struggles intensified in China. Workers were fighting for better wages. In Shanghai alone, there were over 450 strikes between 1919 and 1923.[6]

The French historian Lucien Bianco, however, is among those who question whether imperialism and “feudalism” explain the revolution.[7] He points out that the Chinese Communist Party did not have great success until the Japanese invasion of China after 1937. Before the war, the peasantry was not ready for revolution; economic reasons were not enough to mobilize them. More important was nationalism: “It was the war that brought the Chinese peasantry and China to revolution; at the very least, it considerably accelerated the rise of the CCP to power.”[8] The communist revolutionary movement had a doctrine, long-term objectives, and a clear political strategy that allowed it to adjust to changes in the situation. He adds that the most important aspect of the Chinese Communist movement is that it was armed.

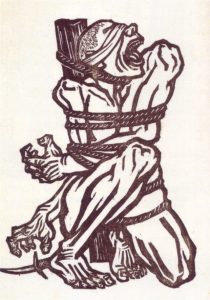

Totalitarian control thus began in China. Artist Li Hua created this woodblock print to express the dehumanization:

Li Hua Roar! (1936) source

Questions to consider:

- Describe what is happening in this image.

- What is the role of the knife on the ground?

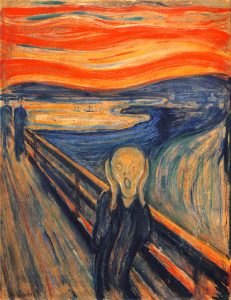

- In what ways is this work similar to Edvard Munch’s Silent Scream?

********************************************

Where IS God? ~ Sartre and Existentialism

Please watch this lecture on Sartre and his philosophy, courtesy of The School of Life:

Sartre’s primary idea is that people, as humans, are “condemned to be free”.[86][full citation needed] This theory relies upon his position that there is no creator, and is illustrated using the example of the paper cutter. Sartre says that if one considered a paper cutter, one would assume that the creator would have had a plan for it: an essence. Sartre said that human beings have no essence before their existence because there is no Creator. Thus: “existence precedes essence”.[86] This forms the basis for his assertion that because one cannot explain one’s own actions and behavior by referring to any specific human nature, they are necessarily fully responsible for those actions. “We are left alone, without excuse.” “We can act without being determined by our past which is always separated from us.”[87]

Sartre maintained that the concepts of authenticity and individuality have to be earned but not learned. We need to experience “death consciousness” so as to wake up ourselves as to what is really important; the authentic in our lives which is life experience, not knowledge.[88] Death draws the final point when we as beings cease to live for ourselves and permanently become objects that exist only for the outside world.[89] In this way death emphasizes the burden of our free, individual existence.

As a junior lecturer at the Lycée du Havre in 1938, Sartre wrote the novel La Nausée (Nausea), which serves in some ways as a manifesto of existentialism and remains one of his most famous books. Taking a page from the German phenomenological movement, he believed that our ideas are the product of experiences of real-life situations, and that novels and plays can well describe such fundamental experiences, having equal value to discursive essays for the elaboration of philosophical theories such as existentialism. With such purpose, this novel concerns a dejected researcher (Roquentin) in a town similar to Le Havre who becomes starkly conscious of the fact that inanimate objects and situations remain absolutely indifferent to his existence. As such, they show themselves to be resistant to whatever significance human consciousness might perceive in them.

He also took inspiration from phenomenologist epistemology, explained by Franz Adler in this way: “Man chooses and makes himself by acting. Any action implies the judgment that he is right under the circumstances not only for the actor, but also for everybody else in similar circumstances.”[90]

This indifference of “things in themselves” (closely linked with the later notion of “being-in-itself” in his Being and Nothingness) has the effect of highlighting all the more the freedom Roquentin has to perceive and act in the world; everywhere he looks, he finds situations imbued with meanings which bear the stamp of his existence. Hence the “nausea” referred to in the title of the book; all that he encounters in his everyday life is suffused with a pervasive, even horrible, taste—specifically, his freedom. The book takes the term from Friedrich Nietzsche‘s Thus Spoke Zarathustra, where it is used in the context of the often nauseating quality of existence. No matter how much Roquentin longs for something else or something different, he cannot get away from this harrowing evidence of his engagement with the world.

The novel also acts as a terrifying realization of some of Immanuel Kant‘s fundamental ideas about freedom; Sartre uses the idea of the autonomy of the will (that morality is derived from our ability to choose in reality; the ability to choose being derived from human freedom; embodied in the famous saying “Condemned to be free”) as a way to show the world’s indifference to the individual. The freedom that Kant exposed is here a strong burden, for the freedom to act towards objects is ultimately useless, and the practical application of Kant’s ideas proves to be bitterly rejected.

Also important is Sartre’s analysis of psychological concepts, including his suggestion that consciousness exists as something other than itself, and that the conscious awareness of things is not limited to their knowledge: for Sartre intentionality applies to the emotions as well as to cognitions, to desires as well as to perceptions.[91] “When an external object is perceived, consciousness is also conscious of itself, even if consciousness is not its own object: it is a non-positional consciousness of itself.”