15 Chapter 15: Globalism and Identity

Learning Objectives ~ Chapter 15 “Globalism and Identity”

- Define globalism

- Explore the impact of globalism on identity

- Consider the way that modern technology and gadgets shift notions of identity

- Discuss how Achebe’s voice gives insight into the long term impact of colonialism on identity

- Discuss the tactics of the Guerrilla Girls

Globalism refers to various systems with scope beyond the merely international. It is used by political scientists, such as Joseph Nye, to describe “attempts to understand all the interconnections of the modern world — and to highlight patterns that underlie (and explain) them.”[1] While primarily associated with world-systems, it can be used to describe other global trends. The term is also used by detractors of globalization such as populist movements.

The term is similar to internationalism and cosmopolitanism.

From the discipline of political science, here are some definitions of globalism:

Paul James defines globalism, “at least in its more specific use […] as the dominant ideology and subjectivity associated with different historically-dominant formations of global extension. The definition thus implies that there were pre-modern or traditional forms of globalism and globalization long before the driving force of capitalism sought to colonize every corner of the globe, for example, going back to the Roman Empire in the second century AD, and perhaps to the Greeks of the fifth-century BC.”[2]

Manfred Steger distinguishes between different globalisms such as justice globalism, jihad globalism, and market globalism.[3] Market globalism includes the ideology of neoliberalism. In some hands, the reduction of globalism to the single ideology of market globalism and neoliberalism has led to confusion. For example, in his 2005 book The Collapse of Globalism and the Reinvention of the World, Canadian philosopher John Ralston Saul treated globalism as coterminous with neoliberalism and neoliberal globalization. He argued that, far from being an inevitable force, globalization is already breaking up into contradictory pieces and that citizens are reasserting their national interests in both positive and destructive ways.

Alternatively, American political scientist Joseph Nye, co-founder of the international relations theory of neoliberalism, generalized the term to argue that globalism refers to any description and explanation of a world which is characterized by networks of connections that span multi-continental distances; while globalization refers to the increase or decline in the degree of globalism.[1] This use of the term originated in, and continues to be used, in academic debates about the economic, social, and cultural developments that is described as globalization.[4] The term is used in a specific and narrow way to describe a position in the debate about the historical character of globalization (i.e. whether globalization is unprecedented or not).

It has been used to describe international endeavours begun after World War II, such as the United Nations, the Warsaw Pact, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and the European Union, and sometimes the later neo-liberal and neoconservative policies of “nation building” and military interventionism between the end of the Cold War in 1991 and the beginning of the War on Terror in 2001.

Proponents of globalism believe in global citizenship; that is, the problems of humanity can be resolved with democratic globalism. Democratic globalism is the idea that all people matter, no matter where they live, and that universal freedom and human rights can be fostered for all mankind.[5] World citizens believe in civic globalism[6] and that by thinking globally and acting locally they can effect positive change across all barriers.

Arguments against globalism are similar to those moved against globalisation, among which loss of cultural identity, deletion of community history, conflict of civilization, loss of political representation and collapse of the democratic process in favour of a globally managed open society.[7] However, the term “globalist” has also been used as a pejorative for political enemies, on the left within the context of the 1990s anti-globalization movement and protests, and on the right as a pejorative of “cosmopolitans” or those who favor internationalist projects over national ones. For example, during the election and presidency of United States president Donald Trump and members of his administration used the term globalist on multiple occasions. The administration was accused of using the term as an anti-Semitic “dog whistle”, to associate their critics with a Jewish conspiracy.

Globalism and Identity

The very theory of Globalism suggests that boundaries are perhaps more fluid. Within the concept of “identity,” that idea provokes reflection on how one’s place, culture, ethnicity and sense of self is affected by these fluid boundaries. How do we see ourselves? How are we seen and understood by others?

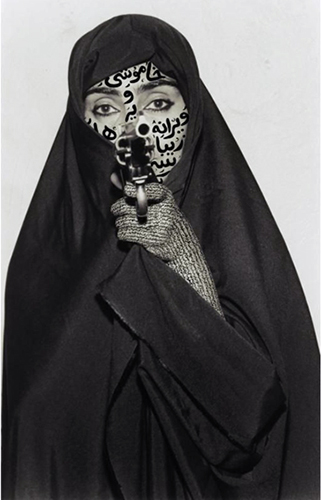

Shirin Neshat is a contemporary Iranian visual artist best known for her work in photography, video, and film (such as her 1999 film Rapture),which explore the relationship between women and the religious and cultural value systems of Islam. She has said that she hopes the viewers of her work “take away with them not some heavy political statement, but something that really touches them on the most emotional level.” Born on March 26, 1957 in Qazin, Iran, she left to study in the United States at the University of California at Berkeley before her the Iranian Revolution in 1979. While her early photographs were overtly political, her film narratives tend to be more abstract, focusing around themes of gender, identity, and society. Her Women of Allah series, created in the mid-1990s, introduced themes of the discrepancies of public and private identities in both Iranian and Western cultures. The split-screened video Turbulent (1998) won Neshat the First International Prize at the Venice Biennale in 1999. The artist currently lives and works in New York, NY. Her works are included in the collections of the Tate Gallery in London, The Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, and the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, among others. Source: Shirin Neshat

The image that opens this chapter is from her Women of Allah series. In Rebellious Silence, the central figure’s portrait is bisected along a vertical seam created by the long barrel of a rifle. Presumably the rifle is clasped in her hands near her lap, but the image is cropped so that the gun rises perpendicular to the lower edge of the photo and grazes her face at the lips, nose, and forehead. The woman’s eyes stare intensely towards the viewer from both sides of this divide.

While the composition—defined by the hard edge of her black chador against the bright white background—appears sparse, measured and symmetrical, the split created by the weapon implies a more violent rupture or psychic fragmentation. A single subject, it suggests, might be host to internal contradictions alongside binaries such as tradition and modernity, East and West, beauty and violence. In the artist’s own words, “every image, every woman’s submissive gaze, suggests a far more complex and paradoxical reality

Most of the subjects in the series are photographed holding a gun, sometimes passively, as in Rebellious Silence, and sometimes threateningly, with the muzzle pointed directly towards the camera lens. With the complex ideas of the “gaze” in mind, we might reflect on the double meaning of the word “shoot,” and consider that the camera—especially during the colonial era—was used to violate women’s bodies. The gun, aside from its obvious references to control, also represents religious martyrdom, a subject about which the artist feels ambivalently, as an outsider to Iranian revolutionary culture. Source: Rebellious Silence

****************************************************

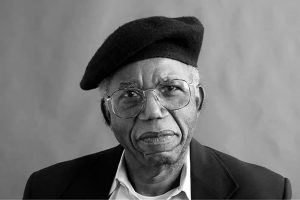

Chinua Achebe (16 November 1930 – 21 March 2013) was a Nigerian novelist, poet, professor, and critic. His first novel Things Fall Apart (1958), often considered his masterpiece, is the most widely read book in modern African literature.

Raised by his parents in the Igbo town of Ogidi in southeastern Nigeria, Achebe excelled at school and won a scholarship to study medicine, but changed his studies to English literature at University College (now the University of Ibadan). He became fascinated with world religions and traditional African cultures, and began writing stories as a university student. After graduation, he worked for the Nigerian Broadcasting Service (NBS) and soon moved to the metropolis of Lagos. He gained worldwide attention for his novel Things Fall Apart in the late 1950s; his later novels include No Longer at Ease (1960), Arrow of God (1964), A Man of the People (1966), and Anthills of the Savannah (1987). Achebe wrote his novels in English and defended the use of English, a “language of colonisers”, in African literature. In 1975, his lecture “An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness” featured a criticism of Joseph Conrad as “a thoroughgoing racist”; it was later published in The Massachusetts Review amid some controversy.

When the region of Biafra broke away from Nigeria in 1967, Achebe became a supporter of Biafran independence and acted as ambassador for the people of the new nation. The civil war that took place over the territory, commonly known as the Nigerian Civil War, ravaged the populace, and as starvation and violence took its toll, he appealed to the people of Europe and the Americas for aid. When the Nigerian government retook the region in 1970, he involved himself in political parties but soon resigned due to frustration over the corruption and elitism he witnessed. He lived in the United States for several years in the 1970s, and returned to the U.S. in 1990, after a car crash left him partially disabled.

A titled Igbo chief himself,[5] Achebe’s novels focus on the traditions of Igbo society, the effect of Christian influences, and the clash of Western and traditional African values during and after the colonial era. His style relies heavily on the Igbo oral tradition, and combines straightforward narration with representations of folk stories, proverbs, and oratory. He also published a large number of short stories, children’s books, and essay collections.

Upon Achebe’s return to the United States in 1990, he began an eighteen-year tenure at Bard College as the Charles P. Stevenson Professor of Languages and Literature. From 2009 until his death, he served as David and Marianna Fisher University Professor and Professor of Africana Studies at Brown University.

A prevalent theme in Achebe’s novels is the intersection of African tradition (particularly Igbo varieties) and modernity, especially as embodied by European colonialism. The village of Umuofia in Things Fall Apart, for example, is violently shaken with internal divisions when the white Christian missionaries arrive. Nigerian English professor Ernest N. Emenyonu describes the colonial experience in the novel as “the systematic emasculation of the entire culture”.[167] Achebe later embodied this tension between African tradition and Western influence in the figure of Sam Okoli, the president of Kangan in Anthills of the Savannah. Distanced from the myths and tales of the community by his Westernised education, he does not have the capacity for reconnection shown by the character Beatrice.[168]

The colonial impact on the Igbo in Achebe’s novels is often effected by individuals from Europe, but institutions and urban offices frequently serve a similar purpose. The character of Obi in No Longer at Ease succumbs to colonial-era corruption in the city; the temptations of his position overwhelm his identity and fortitude.[169] The courts and the position of District Commissioner in Things Fall Apart likewise clash with the traditions of the Igbo, and remove their ability to participate in structures of decision-making.[170]

The standard Achebean ending results in the destruction of an individual and, by synecdoche, the downfall of the community. Odili’s descent into the luxury of corruption and hedonism in A Man of the People, for example, is symbolic of the post-colonial crisis in Nigeria and elsewhere.[171] Even with the emphasis on colonialism, however, Achebe’s tragic endings embody the traditional confluence of fate, individual and society, as represented by Sophocles and Shakespeare.[172]

Still, Achebe seeks to portray neither moral absolutes nor a fatalistic inevitability. In 1972, he said: “I never will take the stand that the Old must win or that the New must win. The point is that no single truth satisfied me—and this is well founded in the Igbo world view. No single man can be correct all the time, no single idea can be totally correct.”[173] His perspective is reflected in the words of Ikem, a character in Anthills of the Savannah: “whatever you are is never enough; you must find a way to accept something, however small, from the other to make you whole and to save you from the mortal sin of righteousness and extremism.”[174] And in a 1996 interview, Achebe said: “Belief in either radicalism or orthodoxy is too simplified a way of viewing things … Evil is never all evil; goodness on the other hand is often tainted with selfishness.”

Source: Chinua Achebe

*************************************************

The Gorilla Girls

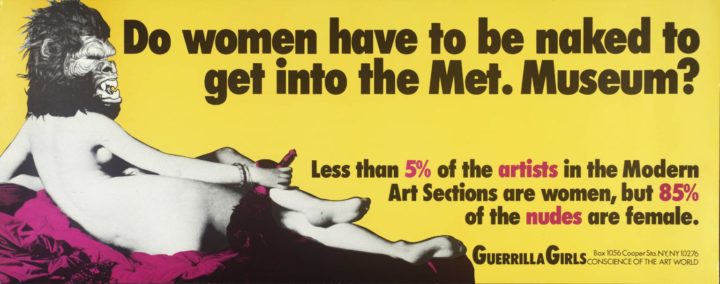

Do Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into the Met. Museum?

1989

Guerrilla Girls

Purchased 2003 http://www.tate.org.uk/art/work/P78793

In 1985, a group of vigilantes wearing gorilla masks took to the streets. Armed with wheat paste and posters, the Guerrilla Girls, as they called themselves, set out to shame the art world for its underrepresentation of women artists. Their posters, in the words of one critic “were rude; they named names and they printed statistics. They embarrassed people. In other words, they worked.” In addition to posters (now highly-valued works of art), billboards, performances, protests, lectures, installations, and limited-edition prints make up the Guerrilla Girls’ varied oeuvre. Their unorthodox tactics were instrumental in making progress. The group is still going strong, reminding the art world that it still has a long way to go. Referring to themselves as “the conscience of the art world,” wherever discrimination lurks, the Guerrilla Girls are likely to strike again.

As their reputation has grown, they have encompassed targets beyond the art sphere, like Hollywood, right wing politicians, and same-sex marriage. They have collaborated with institutions that once shunned them, including the Tate Modern and MoMA, and yet their tactics remain as radical as ever. In a 2012 interview they revealed, “We’ve been working on a weapon, an estrogen bomb…If you drop it, the men will drop their guns and start hugging each other. They’ll say, ‘Why don’t we clean this place up?’ In the end, we encourage people to send their extra estrogen pills to Karl Rove; he needs a little more estrogen.”

The 1989 piece titled “Do Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into the Met. Museum?” addresses the sexualization of women’s bodies in highly regarded paintings and artwork, and how ironically, “85% of the nudes are female” in The Metropolitan Museum of Art (an art museum in New York City), while “less than 5% of the artists in the modern art section are female”.

“Do Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into the Met. Museum?” is notable for many reasons. Firstly, this is one of the first posters produced by the Guerrilla Girls’ that uses a variety of eye-catching colors as opposed to previous posters which were black and white, or utilized one color. This piece uses grayscale in addition to the bright colors pink and yellow, which almost create the illusion of vibration when juxtaposed. Secondly, up until this point the Guerrilla Girls’ posters made effective use of text based posters. But this poster incorporates imagery in addition to statics the Guerrilla Girls gathered while spending a day surveying the Met. They parodied a famous nude painting of a woman, La Grande Odalisque by Jean-August-Dominique Ingres, by taking the naked figure laying back in a relaxed position and placing a gorilla head over her face. Third, it really showed the boldness and passion for equal representation that the Guerrilla Girls possessed, as they went after the Met with the intention of shaming and humiliating such a prestigious art institution.

This poster also demonstrated their advertisement minded design in their choice of colors to get people’s attention, the bold typeface used, and use of color text to emphasize important elements of the statistics. Making it even more advertisement-like, the Guerrilla Girls paid for the poster put on the sides of New York City buses in the advertising spaces, until an outraged public caused the bus companies to disallow it from being shown. People were shocked, as they deemed the figure indecent and suggestive.

The work has been described as “iconic”(Seiferle), as it encompasses the style of the Guerrilla Girls: humor, use of facts and statistics, and advertisement style that can be found in so many of their works.

Sources Cited:

Manchester, Elizabeth. “Do women have to be naked to get Into the Met.Musem?.” Tate.org.uk, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/guerrilla-girls-do-women-have-to-be-naked-to-get-into-the-met-museum-p78793.

Seiferle, Rebecca. “The Guerrilla Girls Artist Overview and Analysis.” TheArtStory.org, http://www.theartstory.org/artist-guerrilla-girls.htm.

Source: Guerilla Girls