2 Chapter 2: Global Voices for Reform

Learning Objectives~ Chapter 2 “Global Voices for Reform”

- Examine how literature and visual art presented counterpoint perspective on contemporary issues

- Consider how the arts are a ‘safe platform’ for examining ideas

- Describe Hieronymus Bosch’s expression of the human experience

- Discuss how artists and musicians of our time use their art to express counter culture and/or the need for social reform

The arts and humanities are unique in that they are disciplines that allow for a multitude of expressive forms. Language is not generally used in the visual arts and yet it is here where we can discover the most convincing arguments and the most nuanced perspectives. In this Chapter we will look at the ways that artists used their work to voice an opinion that was contrary to the status quo or maybe merely a point of view that was unconventional and therefore dangerous. The three artists we will look at are:

- Kabir

- Peter Bruegel the Elder

- Hieronymus Bosch

**************************

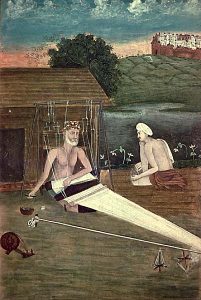

We begin this chapter here, with an image. This is a print done in 1825, of the Indian poet, Kabir. He is at his loom, patiently creating a textile out of singular threads. Weaving is an art form, to be sure; however, Kabir’s true artistry was in his poetry. Think of the ways that weaving mimics poetry.

(Kabir weaving. print. 1825.)

During the 15th century in India, there lived a great reformer who was critical of the “established” religions of Hinduism and Islam. His name was Kabir and he used poetry as his weapon to express what he saw as hypocrisy within these religions and their leaders. Very much along the lines of other reformers like Socrates, Jesus Christ, Muhammad, and Martin Luther, he saw very clearly that when religious belief becomes institutionalized, it loses its way. It can lose its ultimate purpose, which is to show the path toward enlightenment.

The wiki page for Kabir gives us a good sense of historical context: Kabir

From the Guttenberg project we have much of Kabir’s work translated and presented: GP Kabir

Please read the introduction to get a sense of Kabir’s life and work. Then scroll down to read the first 5 poems listed.

Here is an example of the boldness of Kabir’s poetry:

I. 13. mo ko kahân dhûnro bande

O servant, where dost thou seek Me?

Lo! I am beside thee.

I am neither in temple nor in mosque: I am neither in Kaaba nor

in Kailash:

Neither am I in rites and ceremonies, nor in Yoga and

renunciation.

If thou art a true seeker, thou shalt at once see Me: thou shalt

meet Me in a moment of time.

Kabîr says, “O Sadhu! God is the breath of all breath.”

In this poem are striking parallels to Martin Luther’s call for reform in Christian practice of his day. Written in first person, it is the voice of God. That in itself is quite bold! God, or The Divine, has been called by an individual (Kabir). Where are You? God responds by saying that He/She in not to be found in temples, mosques, in ceremonies or practices. Rather, He says, I can be found in “moment of time.” In fact, right here, right now. As you breathe, I am here.

Kabir was a mystic. His work represented a very progressive approach to religious practice.

*************************************

Peter Bruegel the Elder was a Flemish Renaissance painter who is known for his genre paintings and prints. When you think of Renaissance art you might think of works that present lofty subject matter. Scenes from the biblical narrative, moments from mythology, grand aristocratic portraits or historical scenes. However, the term “genre painting” refers to s subject matter that is, well, common. Genre art is scenes of everyday life. Everyday people doing what they do. Later on when we get to the Dutch Golden Age you will see how influential Peter Bruegel’s work was on the Dutch masters.

This painting is a fine example of Bruegel’s work. It is entitled Blind Leading the Blind (1568) and in it you see it depicts the Biblical parable of the blind leading the blind from the Gospel of Matthew 15:14, and is in the collection of the Museo di Capodimonte in Naples, Italy.

The painting reflects Bruegel’s mastery of observation. Each figure has a different eye affliction, including corneal leukoma, atrophy of globe and removed eyes. The men hold their heads aloft to make better use of their other senses. The diagonal composition reinforces the off-kilter motion of the six figures falling in progression. It is considered a masterwork for its accurate detail and composition. Bruegel painted The Blind the year before his death. It has a bitter, sorrowful tone, which may be related to the establishment of the Council of Troubles in 1567 by the government of the Spanish Netherlands. The council ordered mass arrests and executions to enforce Spanish rule and suppress Protestantism. The placement of Sint-Anna Church of the village Sint-Anna-Pede has led to both pro- and anti-Catholic interpretations, though it is not clear that the painting was meant as a political statement.

Can a poet from the 20th century give us some insight into this Renaissance painting? Perhaps. Here is the poem “The Parable of the Blind” by Puerto Rican American poet, William Carlos Williams (1883-1963):

This horrible but superb painting

the parable of the blind

without a red

in the composition shows a group

of beggars leading

each other diagonally downward

across the canvas

from one side

to stumble finally into a bog

where the picture

and the composition ends back

of which no seeing man

is represented the unshaven

features of the des-

titute with their few

pitiful possessions a basin

to wash in a peasant

cottage is seen and a church spire

the faces are raised

as toward the light

there is no detail extraneous

to the composition one

follows the others stick in

hand triumphant to disaster

What is particularly evocative and terrifying, frankly, of the idea that leaders and followers are both lost? Listen to this song by Mumford and Sons:

Forget about the poor ’cause I don’t like the word

And I need to know the name of my neighbor

I am not known if I’m not seen or heard

And I am afraid of that which I do not know

So why don’t I just ask your fucking name

Justice just gets buried in a white light

I heard there was a time we’d call it shame

And I will be here

When you’re crying out tonight

I will be here

Imagine my relief to hit the walls

Running from the weight of ancient labels

Believing what identity there was

Well, my generation’s stuck in the mirror

Forget about the poor ’cause I don’t like the word

And I need to know the name of my neighbor

I am not known if I’m not seen or heard

And I will be here

When you’re crying out tonight

I will be here

Leave it all behind

Don’t be afraid for a moment

The blind leading the blind

I will be here

And when you’re crying out tonight

I will be here

Peter Bruegel the Elder used painting to express a unique and provocative point of view. He was prolific, indeed. Here is the wikipedia page that gives you a context for his life and some other examples of his work. As you peruse this entry I want you to pay particular attention to the sections on his genre works as well as the piece The Procession to Calvary.

Hieronymus Bosch (1450-1516) was a Netherlandish/Dutch painter whose work was considered so odd that it took centuries for art historians to take it into serious consideration. His work shows an active imagination… THAT is an understatement! It is fantastical. Something out of science fiction. It suggests knowledge of the occult and alchemy. It alludes to Christian dogma. It defies a clear category. Perhaps this is why Bosch tends to be a favorite of students in my classes.

The wiki page on Bosch, though short, gives you some interesting background. Please read this to get a sense of his life and some of his major works: Bosch

Here is his painting Christ Before Pilate (1520). “Reading” a painting is all about close observation. What is being emphasized? In what ways are the figures arranged? How is light and dark used for effect? What elements of visual rhetoric do you detect? From the Christian narrative, this is the moment when Jesus Christ is brought before the Roman governor Pontius Pilate. Jesus has been accused of causing insurrection, rabble rousing, causing trouble in the Roman province of Judea. He is brought before Pilate to recant, to state his case.

The soft face of Jesus is encompassed by the harsh and rather ugly faces of those who are condemning him. Is there an ironic twist here? In creating this stark visual contrast, is Bosch prompting us to think about the irony of Christ’s sacrifice, which was intended for the salvation of all, being for the souls of such hideous and deplorable characters as we see here?

Bosch’s work gives us a world of ideas to contemplate. And we will never know what his intent was. He left no diaries, journals or explanations of his work. However, intention aside, what is truly remarkable for us is that these works still speak to us of ideas and concepts that are so much a part of the human experience. We can indeed gain great insight from these early Renaissance voices.