Susan B. Anthony (L) and Elizabeth Cady Stanton (R)

Learning Objectives ~ Chapter 9 “Shaping a New Imperialism”

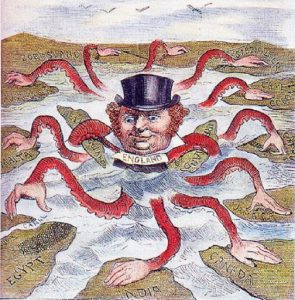

British Imperialism as Octopus (cartoon). Source: wiki commons

This cartoon from a 19th century British periodical captures perfectly both the activity and ethos of New Imperialism. In the center, the center of the world no less, is England. Characterized by a dapper looking, white Anglo-Saxon Protestant, upper class man, England literally and figuratively has its tentacles holding on to all continents. His expression is smug, as if it is his right and perhaps even his duty to place his white hands on other countries. In doing so, England is asserting itself and it is doing so because of its desire to not only be the Empire on which the sun never sets, but also to set forth a mission to “civilize” other nations.

In historical contexts, New Imperialism characterizes a period of colonial expansion by European powers, the United States, and Japan during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The period featured an unprecedented pursuit of overseas territorial acquisitions. At the time, states focused on building their empires with new technological advances and developments, expanding their territory through conquest, and exploiting the resources of the subjugated countries. During the era of New Imperialism, the Western powers (and Japan) individually conquered almost all of Africa and parts of Asia. The new wave of imperialism reflected ongoing rivalries among the great powers, the economic desire for new resources and markets, and a “civilizing mission” ethos.

The “civilizing mission” ethos has been used throughout history, from the middle ages and into the 20th century. It can be understood as a rationale for intervention or colonization, purporting to contribute to the spread of civilization, and used mostly in relation to the Westernization of indigenous peoples, the search for cheap (or free) labor, and the exploitation of natural resources. As Karl Marx points out, the civilizing mission is also a guise for the spread of capitalism.

In terms of British New Imperialism, a poem by Rudyard Kipling describes the vantage point of the colonizers and defends their mission.

“The White Man’s Burden”

Take up the White Man’s burden—

Send forth the best ye breed—

Go bind your sons to exile

To serve your captives’ need;

To wait in heavy harness

On fluttered folk and wild—

Your new-caught, sullen peoples,

Half devil and half child.

Take up the White Man’s burden—

In patience to abide,

To veil the threat of terror

And check the show of pride;

By open speech and simple,

An hundred times made plain.

To seek another’s profit,

And work another’s gain.

Take up the White Man’s burden—

The savage wars of peace—

Fill full the mouth of Famine

And bid the sickness cease;

And when your goal is nearest

The end for others sought,

Watch Sloth and heathen Folly

Bring all your hopes to nought.

Take up the White Man’s burden—

No tawdry rule of kings,

But toil of serf and sweeper—

The tale of common things.

The ports ye shall not enter,

The roads ye shall not tread,

Go make them with your living,

And mark them with your dead!

Take up the White Man’s burden—

And reap his old reward:

The blame of those ye better,

The hate of those ye guard—

The cry of hosts ye humour

(Ah, slowly!) toward the light:—

“Why brought ye us from bondage,

Our loved Egyptian night?”

Take up the White Man’s burden—

Ye dare not stoop to less—

Nor call too loud on Freedom

To cloak your weariness;

By all ye cry or whisper,

By all ye leave or do,

The silent, sullen peoples

Shall weigh your Gods and you.

Take up the White Man’s burden—

Have done with childish days—

The lightly profferred laurel,

The easy, ungrudged praise.

Comes now, to search your manhood

Through all the thankless years,

Cold-edged with dear-bought wisdom,

The judgment of your peers!

Source: White Man’s Burden

Kipling’s poem expresses imperialist ideology. That is, the racial superiority of white Europeans (and North Americans) over dark-skinned people, the idea that this is a heroic deed and one that is thus sanctified by God, and the sort of condescending paternal relationship to non-European cultures. Social Darwinism, a social theory loosely based on Charles Darwin’s theories of the natural world, was widely popular and had a clear impact on how Europeans imagined the dynamic between white races and “others.”

Though Kipling dedicated this poem to the United States on its annexation of the Philippines in 1899, it expresses keenly the same sensibility behind British, French and German colonial land-grabs as well.

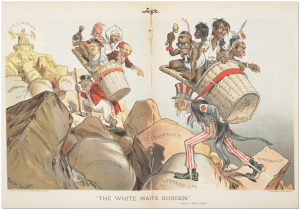

For even more insight on the civilizing mission ethos, this cartoon by Victor Gilliam, which appeared in Judge magazine in 1899, is stark in its caricature of native peoples as “new caught” and “half-devil and half-child.”

This cartoon shows Uncle Sam and John Bull (the United States and England) carrying their new-found “possessions” up a steep incline. The hill they are climbing include broad steps, or boulders, on which are written the various vices (barbarism, oppression, cruelty, ignorance, etc.) that must be overcome on the path toward “civilization.” But one wonders whether there is some irony embedded in this image. For a clearer view, please click on the below link:

New Imperialism and the sort of “manifest destiny” ethos and justification set the stage for industrialism, the spread of capitalism, the growth of nationalism and ultimately the violence of the first World War. This chapter explores the ideas that fueled that progression.

****************************************************************************************************

The Industrial Revolution marked a period of development in the latter half of the 18th century that transformed largely rural, agrarian societies in Europe and America into industrialized, urban ones. Goods that had once been painstakingly crafted by hand started to be produced in mass quantities by machines in factories, thanks to the introduction of new machines and techniques in textiles, iron making and other industries. Fueled by the game-changing use of steam power, the Industrial Revolution began in Britain and spread to the rest of the world, including the United States, by the 1830s and ‘40s. Modern historians often refer to this period as the First Industrial Revolution, to set it apart from a second period of industrialization that took place from the late 19th to early 20th centuries and saw rapid advances in the steel, electric and automobile industries.

In this segment from the online History channel, please read the overviews of the growth of industrialism due to new technologies, the railroad, production techniques and the impact that all of this had on the working class.

For even more insight on these issues, please view this lecture from the Khan Academy:

Alt link: here

The idea that there is a human cost in all this progress was at the core of various calls for reform. The boom of industrialization created a polarization of the world: the oft referred to “haves and have-nots.” This phrase encapsulates Marxist Theory, a somewhat radical social and economic theory that had an enormous impact on the 19th and 20th centuries.

************************************************************************************************

Marxism: “Let the ruling classes tremble…”

“The worker of the world has nothing to lose but their chains. Workers of the world, unite!” Karl Marx

As a university student, Karl Marx (1818-1883) joined a movement known as the Young Hegelians, who strongly criticized the political and cultural establishments of the day. He became a journalist, and the radical nature of his writings would eventually get him expelled by the governments of Germany, France and Belgium. In 1848, Marx and fellow German thinker Friedrich Engels published “The Communist Manifesto,” which introduced their concept of socialism as a natural result of the conflicts inherent in the capitalist system. Marx later moved to London, where he would live for the rest of his life. In 1867, he published the first volume of “Capital” (Das Kapital), in which he laid out his vision of capitalism and its inevitable tendencies toward self-destruction, and took part in a growing international workers’ movement based on his revolutionary theories.

Please view this lecture on Marx, his life and work: Historychannel

In The Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels present their social theory which was largely based on their observations of the lives of the working class in Britain. The modern production practices had a demeaning effect on workers, sapping their physical, emotional and spiritual reserves. Marx observed:

“Modern industry has converted the little workshop of the patriarchal master into the great factory of the industrial capitalist. Masses of labourers, crowded into the factory, are organised like soldiers. As privates of the industrial army they are placed under the command of a perfect hierarchy of officers and sergeants. Not only are they slaves of the bourgeois class, and of the bourgeois State; they are daily and hourly enslaved by the machine, by the over-looker, and, above all, by the individual bourgeois manufacturer himself. The more openly this despotism proclaims gain to be its end and aim, the more petty, the more hateful and the more embittering it is.

The less the skill and exertion of strength implied in manual labour, in other words, the more modern industry becomes developed, the more is the labour of men superseded by that of women. Differences of age and sex have no longer any distinctive social validity for the working class. All are instruments of labour, more or less expensive to use, according to their age and sex.”

Here is the link to the entire Communist Manifesto. I invite you to read the Introduction and Chapter 1: The Bourgeois and the Proletarians. How does Marx describe the lives of these two classes? What details does he use? What sort of rhetorical strategies are apparent?

***************************************************************************************************

Women of the World, Unite!: The Dawn of Organized Suffrage

Image: Suffragettes, London. 1912. link

In England, John Stuart Mill became an unexpected champion for women’s rights and the social reform necessary to fulfill the promises of freedom made through revolutions of the previous century. JS Mill was a British philosopher, political economist, and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of classical liberalism, he contributed widely to social theory, political theory, and political economy. Dubbed “the most influential English-speaking philosopher of the nineteenth century”, Mill’s conception of liberty justified the freedom of the individual in opposition to unlimited state and social control.

In 1851, Mill married Harriet Taylor after 21 years of intimate friendship. Taylor was married when they met, and their relationship was close but generally believed to be chaste during the years before her first husband died in 1849. The couple waited two years before marrying in 1851. Brilliant in her own right, Taylor was a significant influence on Mill’s work and ideas during both friendship and marriage. His relationship with Harriet Taylor reinforced Mill’s advocacy of women’s rights. J. S. Mill said that in his stand against domestic violence, and for women’s rights he was “chiefly an amanuensis to my wife”. He called her mind a “perfect instrument”, and said she was “the most eminently qualified of all those known to the author”. He cites her influence in his final revision of On Liberty, which was published shortly after her death. Taylor died in 1858 after developing severe lung congestion, after only seven years of marriage to Mill.

Between the years 1865 and 1868 Mill served as Lord Rector of the University of St. Andrews. During the same period, 1865–68, he was a Member of Parliament for City and Westminster. He was sitting for the Liberal Party. During his time as an MP, Mill advocated easing the burdens on Ireland. In 1866, Mill became the first person in the history of Parliament to call for women to be given the right to vote, vigorously defending this position in subsequent debate. Mill became a strong advocate of such social reforms as labour unions and farm cooperatives. In Considerations on Representative Government, Mill called for various reforms of Parliament and voting, especially proportional representation, the single transferable vote, and the extension of suffrage. In April 1868, Mill favored in a Commons debate the retention of capital punishment for such crimes as aggravated murder; he termed its abolition “an effeminacy in the general mind of the country.” source

The Subjection of Women is a fascinating read. It is also a challenging one because it is highly intellectual and full of the 19th century rhetorical writing style! However, the strength of this work lies in Mill’s insistence that this be a kind of scientific or philosophical study. The ideas that women should have rights that thus did not confine them to the traditional and conventional ideas of chasteness, propriety, motherhood, a dutiful wife …. all emblems of a social status quo in patriarchy. In one section, Mill expresses the dynamic of the master/slave relationship. As Mill sees it, there are two types of slave, the unwilling one and the willing one. Women remain “willing slaves” simply because there are no other options for them in a society that leaves them with no human rights and at the whim of the men in their lives:

“All causes, social and natural, combine to make it unlikely that women should be collectively rebellious to the power of men. They are so far in a position different from all other subject classes, that their masters require something more from them than actual service. Men do not want solely the obedience of women, they want their sentiments. All men, except the most brutish, desire to have, in the woman most nearly connected with them, not a forced slave but a willing one, not a slave merely, but a favourite. [Pg 27]They have therefore put everything in practice to enslave their minds. The masters of all other slaves rely, for maintaining obedience, on fear; either fear of themselves, or religious fears. The masters of women wanted more than simple obedience, and they turned the whole force of education to effect their purpose. All women are brought up from the very earliest years in the belief that their ideal of character is the very opposite to that of men; not self-will, and government by self-control, but submission, and yielding to the control of others. All the moralities tell them that it is the duty of women, and all the current sentimentalities that it is their nature, to live for others; to make complete abnegation of themselves, and to have no life but in their affections. And by their affections are meant the only ones they are allowed to have—those to the men with whom they are connected, or to the children who constitute an additional and indefeasible tie between them and a man. When we put together three things—first, the natural attraction between opposite sexes; secondly, the wife’s entire dependence on the husband, every privilege or pleasure she has being either his gift, or depending entirely on his will; and lastly, that the principal object of human pursuit, consideration, and all objects of social ambition, can in general be sought or obtained by her only through [Pg 28]him, it would be a miracle if the object of being attractive to men had not become the polar star of feminine education and formation of character. And, this great means of influence over the minds of women having been acquired, an instinct of selfishness made men avail themselves of it to the utmost as a means of holding women in subjection, by representing to them meekness, submissiveness, and resignation of all individual will into the hands of a man, as an essential part of sexual attractiveness. Can it be doubted that any of the other yokes which mankind have succeeded in breaking, would have subsisted till now if the same means had existed, and had been as sedulously used, to bow down their minds to it?”

Please see the entire work here, paying special attention to pages 26-28. In addition, the wiki page on The Subjection of Women is also helpful for an overview of his argument:

*******

Meanwhile, in the United States,

Susan B. Anthony (L) and Elizabeth Cady Stanton (R)

The woman suffrage movement actually began in 1848, when a women’s rights convention was held in Seneca Falls, New York. The Seneca Falls meeting was not the first in support of women’s rights, but suffragists later viewed it as the meeting that launched the suffrage movement. For the next 50 years, woman suffrage supporters worked to educate the public about the validity of woman suffrage. Under the leadership of Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and other women’s rights pioneers, suffragists circulated petitions and lobbied Congress to pass a constitutional amendment to enfranchise women.

At the turn of the century, women reformers in the club movement and in the settlement house movement wanted to pass reform legislation. However, many politicians were unwilling to listen to a disenfranchised group. Thus, over time women began to realize that in order to achieve reform, they needed to win the right to vote. For these reasons, at the turn of the century, the woman suffrage movement became a mass movement.

Alice Paul

In the 20th century leadership of the suffrage movement passed to two organizations. The first, the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), under the leadership of Carrie Chapman Catt, was a moderate organization. The NAWSA undertook campaigns to enfranchise women in individual states, and simultaneously lobbied President Wilson and Congress to pass a woman suffrage Constitutional Amendment. In the 1910s, NAWSA’s membership numbered in the millions.

The second group, the National Woman’s Party (NWP), under the leadership of Alice Paul, was a more militant organization. The NWP undertook radical actions, including picketing the White House, in order to convince Wilson and Congress to pass a woman suffrage amendment.

In 1920, due to the combined efforts of the NAWSA and the NWP, the 19th Amendment, enfranchising women, was finally ratified. This victory is considered the most significant achievement of women in the Progressive Era. It was the single largest extension of democratic voting rights in our nation’s history, and it was achieved peacefully, through democratic processes.

College day in the picket line