10 Chapter 10 – Toxic Substances, and Occupational Health and Safety

Toxic Substances

What is toxicology?

Toxicology is a field of science that helps us understand the harmful effects that chemicals, substances, or situations, can have on people, animals, and the environment. Some refer to toxicology as the “Science of Safety” because as a field it has evolved from a science focused on studying poisons and adverse effects of chemical exposures, to a science devoted to studying safety.

Toxicology uses the power of science to predict what, and how chemicals may cause harm and then shares that information to protect public health. When talking about toxicology it is important to keep a few things in mind.

- Not everyone will respond to substances in exactly the same way. Many factors, including the amount and duration of exposure, an individual’s susceptibility to a substance, and a person’s age, all impact whether a person will develop a disease or not. There are times in a person’s life when he or she may be more susceptible to chemicals. These times may include periods of active cell differentiation and growth in the womb and in early childhood, as well as during adolescence, when the brain is continuing to develop. Just because someone is exposed to a harmful substance, does not always mean they will get sick from it.

- The dose of the chemical or substance a person is exposed to is another important factor in toxicology. All substances have the potential to be toxic if given to humans and other living organisms in certain conditions and at certain doses or levels. For example, one or two aspirins may be good for you, but taking a bottle of aspirin may be harmful. The field of toxicology tries to understand and identify at what dose and through what exposure a substance poses a hazard.

- Toxicologists also realize that even low-dose exposures that may seem insignificant may have biological meaning or lead to an adverse health effect if the exposure is continuous or happens during a critical window of development.

- For this assignment, you will review the Safety Data Sheet (SDS) for DDT. Safety Data Sheets are intended to provide a variety of information related to a chemical. Most recently, such sheets were called Material Safety Data Sheets. Through a global agreement, all the sheets were changed in what was called a global harmonization process– this means that all sheets are now uniform throughout the world.

In addition to reviewing the sources, you will make a copy of the assignment worksheet and compose an essay which you will submit using the assignment link in this folder.

Downloading and Saving Your Worksheet

Reviewing Sources About the SDS for DDT

- Safety Data Sheet [32203 USENG].

- The link above is a safety data sheet for the chemical DDT by RESTEK corporation.Sigma-Aldrich Inc

- Safety Data Sheet [4,4’-DDT]. Chem Service, Inc

- The link above is a safety data sheet for the chemical DDT.

- On the page, click on the View/download link at the far-right side of the page under the SDS Document heading– this will download the SDS for DDT.

- The link above is a safety data sheet for the chemical DDT.

Writing Your Essay

Submitting Your Worksheet

What is a toxicologist?

A toxicologist is a scientist who has a strong understanding of many scientific disciplines, such as biology and chemistry, and typically works with chemicals and other substances to determine if they are toxic or harmful to humans and other living organisms or the environment.

Just like there are different types of doctors, there are different types of toxicology specialists.

A toxicologist working in the pharmaceutical industry, for example, might work to make sure that potential new drugs are safe for testing in clinical trials for humans.

A toxicologist working at the National Toxicology Program (NTP) might be involved in designing and overseeing studies that create a controlled environment that replicates exposures that humans may encounter. NTP toxicologists work to identify hazards from the chemicals or substances they are studying.

What does it mean when toxicologists have D.A.B.T. after their names?

DABT stands for Diplomate of the American Board of Toxicology (DABT). This means that the person has passed several tests and is certified by one of the world’s largest organizations in general toxicology, the American Board of Toxicology (ABT). The Board works to identify, maintain, and to foster a standard for professional competency in the field of toxicology.

How does the science of toxicology improve people’s lives?

Toxicology provides critical information and knowledge that can be used by regulatory agencies, decision makers, and others to put programs and policies in place to limit our exposures to these substances, thereby preventing or reducing the likelihood that a disease or other negative health outcome would occur. For example, the state of California used NTP findings to establish the first in the nation drinking water standard for Hexavalent Chromium. This standard will help reduce people’s exposure to this metallic element. Other benefits of toxicology include:

- Government agencies have a sound scientific basis for establishing regulations and policies aimed at protecting and preserving human health and the environment.

- Companies, such as pharmaceutical and chemical, are able to develop safer products, drugs, and workplaces.

- Consumers have access to information that helps them make decisions about their own health and prevent diseases.

What Is NIEHS Doing?

Supporting grantees across the country. NIEHS has a long history of funding grants in toxicology and environmental health sciences. For example researchers supported through the NIEHS Division of Extramural Research and Training are working to develop new and improved models of toxicity that can help predict cancer and other adverse health outcomes that may result from fetal or early life exposures.

For example, because we know that people are exposed to a multitude of environmental toxicants, NIEHS grantees are working to understand the implications of chemical mixtures, which can sometimes produce health affects greater than each chemical would alone.

Grantees have published some of the first immunotoxic studies linking childhood exposures to perfluorinated compounds (PFCs) with immune system deficiency.

NIEHS supported researchers have also used their toxicology expertise to improve our knowledge and our approaches to chemicals such as arsenic, leady and mercury.

Also, grantees are active participants in our nanotechnology efforts, where we are working to increase our understanding of how engineered nanomaterials interact with living systems, so we can develop predictive models for quantifying exposure from nanomaterials and are able to assess their health impacts. These efforts will help guide the design of second-generation engineered nanomaterials and minimize adverse health effects.

Also, the NIEHS Superfund Research Program works to gain a better understanding of how toxicants affect human health in order to help environmental managers and risk assessors protect the public from exposures to hazardous substances. They accomplish this through research conducted at universities across the country, to develop cost-effective approaches to detect, remove, and/or reduce the amount of toxic substances found in the environment. The program conducts research on remediation, detection, and monitoring tools or strategies and also funds studies that relate to multiple disease endpoints such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, and neurological disorders.[1]

Where Do Toxicologist Work:

The “Job Market Survey” estimates that 9,000 toxicologists are employed in North America. Of recent PhD’s, 53 percent entered industry, 34 percent found positions in academia and 12 percent in government. These numbers are similar to overall employment statistics in the discipline as projected in the “Job Market Survey.”

Comparison with other careers is possible by investigating the Occupational Outlook Handbook produced by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Need for Toxicologist

One of the factors that is driving the need for toxicologist is the aging population. The longer we live the more time a chemical has within our bodies and there for the more likely we are to see toxicological impacts from chemical

Chemical, Consumer Products, Pharmaceutical and Other Industries

Industries are the number one employer of toxicologists (47 percent). Product development, product safety evaluation, and regulatory compliance generate a large job market for toxicologists. Pharmaceutical industries employ 17 percent of toxicologists, and chemical industries employ 7 percent. These industries often employ toxicologists trained at all levels of education. The “Toxicologist Supply and Expertise Survey” found that, of recent graduates, 53 percent of those with PhD’s, 73 percent of those with master’s degrees and 58 percent of those with bachelor’s degrees entered industry. Many industries have their own research and product safety evaluation programs, while others may contract their work to specific research organizations that are managed independently from the industry.

Academic Institutions

Academic institutions are the number two employer of toxicologists (21 percent). The rapid growth in toxicology programs has generated a large and growing market for toxicologists with doctoral level training. Although most of these opportunities are in schools of medicine and/or public health in major universities, smaller colleges are beginning to employ toxicologists to teach toxicology in basic biology, chemistry and engineering programs.

Government

Government is the third largest employer of toxicologists (14 percent). Although most government jobs are with federal regulatory agencies, many states are now beginning to employ toxicologists with master’s degrees.

Consulting

An increasing number of toxicologists are employed in the professional services industry (12 percent). Providing professional guidance and advice to local public agencies, industries and attorneys involved in problems with toxic chemicals is a rapidly growing activity for the experienced toxicologist. Many graduates of baccalaureate and master’s programs in toxicology are finding employment with consulting firms. Individuals with doctoral training and several years of experience in applied toxicology may also find opportunities directing projects and serving as team leaders or administrators in the consulting

Research Foundations

A small proportion of toxicologists pursue research within nonprofit organizations (4 percent). Numerous public and private research foundations employ toxicologists to conduct research on specific problems of industrial or public concern. Toxicologists at all levels of education

Irradiated Foods

Irradiation does not make foods radioactive, compromise nutritional quality, or noticeably change the taste, texture, or appearance of food. In fact, any changes made by irradiation are so minimal that it is not easy to tell if a food has been irradiated.

Food irradiation (the application of ionizing radiation to food) is a technology that improves the safety and extends the shelf life of foods by reducing or eliminating microorganisms and insects. Like pasteurizing milk and canning fruits and vegetables, irradiation can make food safer for the consumer. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is responsible for regulating the sources of radiation that are used to irradiate food. The FDA approves a source of radiation for use on foods only after it has determined that irradiating the food is safe.

Why Irradiate Food?

Irradiation can serve many purposes.

- Prevention of Foodborne Illness – to effectively eliminate organisms that cause foodborne illness, such as Salmonella and Escherichia coli (E. coli).

- Preservation – to destroy or inactivate organisms that cause spoilage and decomposition and extend the shelf life of foods.

- Control of Insects – to destroy insects in or on tropical fruits imported into the United States. Irradiation also decreases the need for other pest-control practices that may harm the fruit.

- Delay of Sprouting and Ripening – to inhibit sprouting (e.g., potatoes) and delay ripening of fruit to increase longevity.

- Sterilization – irradiation can be used to sterilize foods, which can then be stored for years without refrigeration. Sterilized foods are useful in hospitals for patients with severely impaired immune systems, such as patients with AIDS or undergoing chemotherapy. Foods that are sterilized by irradiation are exposed to substantially higher levels of treatment than those approved for general use.

Did you know?

National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) astronauts eat meat that has been sterilized by irradiation to avoid getting foodborne illnesses when they fly in space.

How Is Food Irradiated?

There are three sources of radiation approved for use on foods.

- Gamma rays are emitted from radioactive forms of the element cobalt (Cobalt 60) or of the element cesium (Cesium 137). Gamma radiation is used routinely to sterilize medical, dental, and household products and is also used for the radiation treatment of cancer.

- X-rays are produced by reflecting a high-energy stream of electrons off a target substance (usually one of the heavy metals) into food. X-rays are also widely used in medicine and industry to produce images of internal structures.

- Electron beam (or e-beam) is similar to X-rays and is a stream of high-energy electrons propelled from an electron accelerator into food.

Is Irradiated Food Safe to Eat?

The FDA has evaluated the safety of irradiated food for more than 30 years and has found the process to be safe. The World Health Organization (WHO), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) have also endorsed the safety of irradiated food.

The FDA has approved a variety of foods for irradiation in the United States including:

- Beef and Pork

- Crustaceans (e.g., lobster, shrimp, and crab)

- Fresh Fruits and Vegetables

- Lettuce and Spinach

- Poultry

- Seeds for Sprouting (e.g., for alfalfa sprouts)

- Shell Eggs

- Shellfish – Molluscan

(e.g., oysters, clams, mussels, and scallops) - Spices and Seasonings

How Will I Know if My Food Has Been Irradiated?

The FDA requires that irradiated foods bear the international symbol for irradiation. Look for the Radura symbol along with the statement “Treated with radiation” or “Treated by irradiation” on the food label. Bulk foods, such as fruits and vegetables, are required to be individually labeled or to have a label next to the sale container. The FDA does not require that individual ingredients in multi-ingredient foods (e.g., spices) be labeled. It is important to remember that irradiation is not a replacement for proper food handling practices by producers, processors, and consumers. Irradiated foods need to be stored, handled, and cooked in the same way as non-irradiated foods, because they could still become contaminated with disease-causing organisms after irradiation if the rules of basic food safety are not followed.[2]

Blood Brain Barrier and how it works

This video explains how the process works.

Occupational Health and Safety

10.02 Module 10 Discussion Forum- Link to Blackboard Site

Background Information

- The exposure determination identifies job classifications that are performed by employees by occupational exposure, tasks, and procedures.

- The procedures for evaluating the circumstances surrounding exposure incidents.

- A schedule of how other provisions of the standard are implemented, including methods of compliance; HIV and HBV research laboratories and production facilities requirements; hepatitis B vaccination and post-exposure evaluation and follow-up; communication of hazards to employees; and recordkeeping. Methods of compliance include:

- Universal precautions.

- Engineering and work practice controls, such as safer medical devices, sharps disposal containers, and hand hygiene.

- Personal protective equipment.

- Housekeeping, including decontamination procedures and removal of regulated waste.

- Documentation of:

- The annual consideration and implementation of appropriate commercially available and effective safer medical devices designed to eliminate or minimize occupational exposure, and

- The solicitation of non-managerial health care workers (who are responsible for direct patient care and are potentially exposed to injuries from contaminated sharps) in the identification, evaluation, and selection of effective engineering and work practice controls.

Pre-Discussion Work

- St. Johns County School District

- This document gives you an example of a plan for a school.

- Clicking on the link above will download a Word document, which you should skim through it to get a sense of what is in such a plan.

- This one is short– some school plans are upwards of 50 pages long.

Copying the Worksheet and Completing Part One

Discussing Your Work

The Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 (OSH Act) was passed to prevent workers from being killed or seriously harmed at work. This law created the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), which sets and enforces protective workplace safety and health standards. OSHA also provides information, training, and assistance to employers and workers.

Under the OSH Act, employers have the responsibility to provide a safe workplace.

Employers must:• Follow all relevant OSHA safety and health standards.

• Find and correct safety and health hazards.

• Inform employees about chemical hazards through training, labels, alarms, color-coded systems, chemical information sheets and other methods.

• As of January 1, 2015, notify OSHA within 8 hours of a workplace fatality or within 24 hours of any work-related inpatient hospitalization, amputation or loss of an eye (1-800-321-OSHA [6742]); www.osha.gov/report_online).

• Provide required personal protective equipment at no cost to workers.*

• Keep accurate records of work-related injuries and illnesses.

• Post OSHA citations, injury and illness summary data, and the OSHA Job Safety and Health – It’s The Law poster in the workplace where workers will see them.

• Not retaliate against any worker for using their rights under the law.

Employees have the right to:• Working conditions that do not pose a risk of serious harm.

• Receive information and training (in a language workers can understand) about chemical and other hazards, methods to prevent harm, and OSHA standards that apply to their workplace.

• Review records of work-related injuries and illnesses.

• Get copies of test results done to find and measure hazards in the workplace.

• File a complaint asking OSHA to inspect their workplace if they believe there is a serious hazard or that their employer is not following OSHA rules. When requested, OSHA will keep all identities confidential.

• Use their rights under the law without retaliation. If an employee is fired, demoted, transferred or retaliated against in any way for using their rights under the law, they can file a complaint with OSHA. This complaint must be filed within 30 days of the alleged retaliation.

* Employers must pay for most types of required personal protective equipment.

OSHA STANDARDS

OSHA standards are rules that describe the methods employers are legally required to follow to protect their workers from hazards. Before OSHA can issue a standard, it must go through a very extensive and lengthy process that includes substantial public engagement, notice and comment. The agency must show that a significant risk to workers exists and that there are feasible measures employers can take to protect their workers.

Construction, General Industry, Maritime, and Agriculture standards protect workers from a wide range of serious hazards. These standards limit the amount of hazardous chemicals workers can be exposed to, require the use of certain safe practices and equipment, and require employers to monitor certain workplace hazards.

Examples of OSHA standards include requirements to provide fall protection, prevent trenching cave-ins, prevent exposure to some infectious diseases, ensure the safety of workers who enter confined spaces, prevent exposure to such harmful substances as asbestos and lead, put guards on machines, provide respirators or other safety equipment, and provide training for certain dangerous jobs.

Employers must also comply with the General Duty Clause of the OSH Act. This clause requires employers to keep their workplaces free of serious recognized hazards and is generally cited when no specific OSHA standard applies to the hazard.

InspectionsInspections are initiated without advance notice, conducted using on-site or telephone and facsimile investigations, performed by highly trained compliance officers, and based on the following priorities:

• Imminent danger.

• Catastrophes – fatalities or hospitalizations.

• Worker complaints and referrals.

• Targeted inspections – particular hazards, high injury rates.

• Follow-up inspections.

On-site inspections can be triggered by a complaint from a current worker or their representative if they believe there is a serious hazard or that their employer is not following OSHA standards or rules. Often the best and fastest way to get a hazard corrected is to notify your supervisor or employer.

When an inspector finds violations of OSHA standards or serious hazards, OSHA may issue citations and fines. A citation includes methods an employer may use to fix a problem and the date by when the corrective actions must be completed.Employers have the right to contest any part of the citation, including whether a violation actually exists. Workers only have the right to challenge the deadline for when a problem must be resolved. Appeals of citations are heard by the independent Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission.

Help for EmployersOSHA offers free confidential advice. Several programs and services help employers identify and correct job hazards as well as improve their injury and illness prevention programs.

Free On-Site ConsultationOSHA provides a free service, On-Site Consultation, for small businesses with fewer than 250 workers at a site (and no more than 500 employees nationwide). On-site Consultation services are separate from enforcement and do not result in penalties or citations. Each year, OSHA makes more than 29,000 consultation visits to small businesses to provide free compliance assistance. By working with the OSHA Consultation Program, certain exemplary employers may request participation in OSHA’s Safety and

OSHA has compliance assistance specialists throughout the nation who can provide general information about OSHA standards and compliance assistance resources. Contact your local OSHA office for more information or visit www.osha.gov/dcsp/compliance_assistance/ cas.html.

Cooperative ProgramsOSHA offers cooperative programs to help prevent fatalities, injuries, and illnesses in the workplace. Alliance Program – OSHA works with groups committed to worker safety and health to develop compliance assistance resources and educate workers and employers. OSHA Strategic Partnerships (OSP) – Partnerships are formalized through tailored agreements designed to encourage, assist, and recognize partner efforts to eliminate serious hazards and achieve model workplace

safety and health practices. Voluntary Protection Programs (VPP) – The VPP recognize employers and workers in private industry and federal agencies who have implemented effective safety and health management programs and maintain injury and illness rates below the national average for their respective industries. In VPP, management, labor, and OSHA work cooperatively and proactively to prevent fatalities, injuries, and illnesses.

Information and Education OSHA Training Institute

The OSHA Training Institute (OTI) Education Centers are a national network of nonprofit organizations authorized by OSHA to deliver occupational safety and health training to private sector workers, supervisors, and employers.

Educational Materials

OSHA has a variety of educational materials and electronic tools available on its website at These include utilities such as expert advisors, electronic compliance assistance, videos and other information for employers and workers. OSHA’s software programs and eTools walk you through safety and health issues and common problems to find the best solutions for your workplace.

OSHA’s extensive publications help explain OSHA standards, job hazards, and mitigation strategies and provide assistance in developing effective safety and health programs.

QuickTakes

OSHA’s free, twice-monthly online newsletter, QuickTakes, offers the latest news about OSHA initiatives and products to assist employers and workers in finding and preventing workplace hazards.

Who Does OSHA Cover: Private Sector Workers

OSHA covers most private sector employers and workers in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and other U.S. jurisdictions either directly through Federal OSHA or through an OSHA-approved state program. State-run safety and health programs must be at least as effective as the Federal OSHA program.

State and Local Government Workers State and local government workers are not covered by Federal OSHA, but they do have protections in states that operate their own programs. The following states have approved state programs: AK, AZ, CA, CT, HI, IA, IL, IN, KY, MD, MI, MN, NC, NJ, NM, NV, NY, OR, SC, TN, UT, VA, VT, WA, WY, Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. Connecticut, Illinois, New Jersey, New York and the Virgin Islands programs cover public sector (state and local government) workers only. Federal OSHA covers private sector workers in these jurisdictions.

Federal Government Workers

OSHA’s protection applies to all federal agencies. Although OSHA does not fine federal agencies, it does monitor federal agencies and responds to workers’ complaints.

Not Covered by the OSH Act:

Self-employed workers; and workplace hazards regulated by another federal agency (for example, the Mine Safety and Health Administration, the Department of Energy, or Coast Guard).[3]

The Triangle Waist Company Fire[4]

Even though many workers toiled under one roof in the Asch building, owned by Max Blanck and Isaac Harris, the owners subcontracted much work to individuals who hired the hands and pocketed a portion of the profits. Subcontractors could pay the workers whatever rates they wanted, often extremely low. The owners supposedly never knew the rates paid to the workers, nor did they know exactly how many workers were employed at their factory at any given point. Such a system led to exploitation.Even today, sweatshops have not disappeared in the United States. They keep attracting workers in desperate need of employment and undocumented immigrants, who may be anxious to avoid involvement with governmental agencies. Recent studies conducted by the U.S. Department of Labor found that 67% of Los Angeles garment factories and 63% of New York garment factories violate minimum wage and overtime laws. Ninety-eight percent of Los Angeles garment factories have workplace health and safety problems serious enough to lead to severe injuries or death.The International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union organized workers in the women’s clothing trade. Many of the garment workers before 1911 were unorganized, partly because they were young immigrant women intimidated by the alien surroundings. Others were more daring, though. All were ripe for action against the poor working conditions. In 1909, an incident at the Triangle Factory sparked a spontaneous walkout of its 400 employees. The Women’s Trade Union League, a progressive association of middle class white women, helped the young women workers picket and fence off thugs and police provocation. At a historic meeting at Cooper Union, thousands of garment workers from all over the city followed young Clara Lemlich’s call for a general strike.With the cloakmakers’ strike of 1910, a historic agreement was reached, that established a grievance system in the garment industry. Unfortunately for the workers, though, many shops were still in the hands of unscrupulous owners, who disregarded basic workers’ rights and imposed unsafe working conditions on their employees.

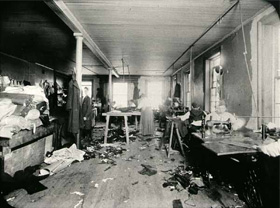

Even though many workers toiled under one roof in the Asch building, owned by Max Blanck and Isaac Harris, the owners subcontracted much work to individuals who hired the hands and pocketed a portion of the profits. Subcontractors could pay the workers whatever rates they wanted, often extremely low. The owners supposedly never knew the rates paid to the workers, nor did they know exactly how many workers were employed at their factory at any given point. Such a system led to exploitation.Even today, sweatshops have not disappeared in the United States. They keep attracting workers in desperate need of employment and undocumented immigrants, who may be anxious to avoid involvement with governmental agencies. Recent studies conducted by the U.S. Department of Labor found that 67% of Los Angeles garment factories and 63% of New York garment factories violate minimum wage and overtime laws. Ninety-eight percent of Los Angeles garment factories have workplace health and safety problems serious enough to lead to severe injuries or death.The International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union organized workers in the women’s clothing trade. Many of the garment workers before 1911 were unorganized, partly because they were young immigrant women intimidated by the alien surroundings. Others were more daring, though. All were ripe for action against the poor working conditions. In 1909, an incident at the Triangle Factory sparked a spontaneous walkout of its 400 employees. The Women’s Trade Union League, a progressive association of middle class white women, helped the young women workers picket and fence off thugs and police provocation. At a historic meeting at Cooper Union, thousands of garment workers from all over the city followed young Clara Lemlich’s call for a general strike.With the cloakmakers’ strike of 1910, a historic agreement was reached, that established a grievance system in the garment industry. Unfortunately for the workers, though, many shops were still in the hands of unscrupulous owners, who disregarded basic workers’ rights and imposed unsafe working conditions on their employees.Near closing time on Saturday afternoon, March 25, 1911, a fire broke out on the top floors of the Asch Building in the Triangle Waist Company. Within minutes, the quiet spring afternoon erupted into madness, a terrifying moment in time, disrupting forever the lives of young workers. By the time the fire was over, 146 of the 500 employees had died. The survivors were left to live and relive those agonizing moments. The victims and their families, the people passing by who witnessed the desperate leaps from ninth floor windows, and the City of New York would never be the same.

Survivors recounted the horrors they had to endure, and passers-by and reporters also told stories of pain and terror they had witnessed. The images of death were seared deeply in their mind’s eye.

Many of the Triangle factory workers were women, some as young as 14 years old. They were, for the most part, recent Italian and European Jewish immigrants who had come to the United States with their families to seek a better life. Instead, they faced lives of grinding poverty and horrifying working conditions. As recent immigrants struggling with a new language and culture, the working poor were ready victims for the factory owners. For these workers, speaking out could end with the loss of desperately needed jobs, a prospect that forced them to endure personal indignities and severe exploitation. Some turned to labor unions to speak for them; many more struggled alone. The Triangle Factory was a non-union shop, although some of its workers had joined the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union.

life. Instead, they faced lives of grinding poverty and horrifying working conditions. As recent immigrants struggling with a new language and culture, the working poor were ready victims for the factory owners. For these workers, speaking out could end with the loss of desperately needed jobs, a prospect that forced them to endure personal indignities and severe exploitation. Some turned to labor unions to speak for them; many more struggled alone. The Triangle Factory was a non-union shop, although some of its workers had joined the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union.

New York City, with its tenements and loft factories, had witnessed a growing concern for issues of health and safety in the early years of the 20th century. Groups such as the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) and the Womens’ Trade Union League (WTUL) fought for better working conditions and protective legislation. The Triangle Fire tragically illustrated that fire inspections and precautions were woefully inadequate at the time. Workers recounted their helpless efforts to open the ninth floor doors to the Washington Place stairs. They and many others afterwards believed they were deliberately locked– owners had frequently locked the exit doors in the past, claiming that workers stole materials. For all practical purposes, the ninth floor fire escape in the Asch Building led nowhere, certainly not to safety, and it bent under the weight of the factory workers trying to escape the inferno. Others waited at the windows for the rescue workers only to discover that the firefighters’ ladders were several stories too short and the water from the hoses could not reach the top floors. Many chose to jump to their deaths rather than to burn alive.

In the weeks that followed, the grieving city identified the dead, sorted out their belongings, and reeled in numbed grief at the atrocity that could have been averted with a few precautions. The International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union proposed an official day of mourning. The grief-stricken city gathered in churches, synagogues, and finally, in the streets.

Protesting voices arose, bewildered and angry at the lack of concern and the greed that had made this possible. The people demanded restitution, justice, and action that would safeguard the vulnerable and the oppressed. Outraged cries calling for action to improve the unsafe conditions in workshops could be heard from every quarter, from the mainstream conservative to the progressive and union press.

Workers flocked to union quarters to offer testimonies, support mobilization, and demand that Triangle owners Harris and Blanck be brought to trial. The role that strong unions could have in helping prevent such tragedies became clear. Workers organized in powerful unions would be more conscious of their rights and better able to obtain safe working conditions.

Shortly after the fire, the Executive Board of the Ladies’ Waist and Dress Makers’ Union, Local No. 25 of the ILGWU,  (the local to which some of the Triangle factory workers belonged), met to plan relief work for the survivors and the families of the victims. Soon several progressive organizations came forward to help with the relief effort. Representatives from the Women’s Trade Union League, the Workmen’s Circle (Arbeiter Ring), the Jewish Daily Forward, and the United Hebrew Trades formed the Joint Relief Committee, which, over the course of the next months, allotted lump sums, often to be remitted abroad, to Russia or Italy.

(the local to which some of the Triangle factory workers belonged), met to plan relief work for the survivors and the families of the victims. Soon several progressive organizations came forward to help with the relief effort. Representatives from the Women’s Trade Union League, the Workmen’s Circle (Arbeiter Ring), the Jewish Daily Forward, and the United Hebrew Trades formed the Joint Relief Committee, which, over the course of the next months, allotted lump sums, often to be remitted abroad, to Russia or Italy.

In addition, its Executive Committee distributed weekly pensions, supervised and cared for the young workers and children placed in institutions of various kinds, and secured work and proper living arrangements for the workers after they recuperated from their injuries.

The Joint Relief Committee worked together with the American Red Cross, which also collected funds from the general public. Estimates indicate that the Joint Relief Committee alone administered about $30,000.

Immediately after the fire, Triangle owners Blanck and Harris declared in interviews that their building was fireproof, and that it had just been approved by the Department of Buildings. Yet the call for bringing those responsible to justice and reports that the doors of the factory were locked at the time of the fire prompted the District Attorney’s office to seek an indictment against the owners. On April 11, a grand jury indicted Harris and Blanck on seven counts, charging them with manslaughter in the second degree under section 80 of the Labor Code, which mandated that doors should not be locked during working hours.

Justice?

On December 27, twenty-three days after the trial had started, a jury acquitted Blanck and Harris of any wrong doing. The task of the jurors had been to determine whether the owners knew that the doors were locked at the time of the fire.

Customarily, the only way out for workers at quitting time was through an opening on the Green Street side, where all pocketbooks were inspected to prevent stealing. Worker after worker testified to their inability to open the doors to their only viable escape route, the stairs to the Washington Place exit, because the Greene Street side stairs were completely engulfed by fire. More testimony supported this fact. Yet the brilliant defense attorney Max Steuer planted enough doubt in the jurors’ minds to win a not-guilty verdict. Grieving families and much of the public felt that justice had not been done. “Justice!” they cried. “Where is justice?”

Twenty-three individual civil suits were brought against the owners of the Asch building. On March 11, 1914, three years after the fire, Harris and Blanck settled. They paid 75 dollars per life lost.

Harris and Blanck were to continue their defiant attitude toward the authorities. Just a few days after the fire, the new premises of their factory had been found not to be fireproof, without fire escapes, and without adequate exits.

In August of 1913, Max Blanck was charged with locking one of the doors of his factory during working hours. Brought to court, he was fined twenty dollars, and the judge apologized to him for the imposition.

In December of 1913, the interior of his factory was found to be littered with rubbish piled six feet high, with scraps kept in non-regulation, flammable wicker baskets. This time, instead of a court appearance and a fine, he was served a stern warning. The Triangle Waist Company was to cease operations in 1918, but the owners maintained throughout that their factory was a “model of cleanliness and sanitary conditions,” and that it was “second to none in the country.”

Sunshine Mine Disaster Kellogg Idaho

The day shift on the morning of May 2, 1972, included 173 men. Around 11:40 a.m., smoke was discovered coming from the 910 raise on the 3700 level. As the smoke spread rapidly throughout the mine, the No. 10 shaft foreman ordered an evacuation at about 12:03 p.m. Men were hoisted from the lower levels to the 3100 level, where they were directed to make their way to the Jewell Shaft. Yet, hoisting stopped at 1:02 p.m. after the hoistman was overcome by smoke and carbon monoxide. Many of the men who reached the 3100 level were also overcome. Of the 173 men in the mine at the time of the fire, 80 were able to evacuate, with the last one reaching the surface by 1:30 p.m. Two men, able to find a safe zone on the 4800 level near the No. 12 borehole, were rescued 175 hours later. The remaining 91 men died of carbon monoxide poisoning. Besides the 31 victims found on the 3100 level, 21 were found on the 5200 level, 16 on 3700, 7 on 4400, 7 on 4800, 4 on 3400, 3 on 4200, and 2 on 5000. (Photo of Memorial Statue [5])

the 910 raise on the 3700 level. As the smoke spread rapidly throughout the mine, the No. 10 shaft foreman ordered an evacuation at about 12:03 p.m. Men were hoisted from the lower levels to the 3100 level, where they were directed to make their way to the Jewell Shaft. Yet, hoisting stopped at 1:02 p.m. after the hoistman was overcome by smoke and carbon monoxide. Many of the men who reached the 3100 level were also overcome. Of the 173 men in the mine at the time of the fire, 80 were able to evacuate, with the last one reaching the surface by 1:30 p.m. Two men, able to find a safe zone on the 4800 level near the No. 12 borehole, were rescued 175 hours later. The remaining 91 men died of carbon monoxide poisoning. Besides the 31 victims found on the 3100 level, 21 were found on the 5200 level, 16 on 3700, 7 on 4400, 7 on 4800, 4 on 3400, 3 on 4200, and 2 on 5000. (Photo of Memorial Statue [5])

The mine was closed for seven months after the fire, one of the worst mining disasters in American history, and the worst disaster in Idaho history. Today, a monument to the lost miners stands besides Interstate 90 near the mine. (Photo

Following the May 1972 disaster when the mine re-opened and full production resumed, the Sunshine regained its position as the number one silver producer in the Nation. In 1979 alone,  Sunshine Mine produced 18% of the Nation’s silver ore. By the end of 1988, the mine was at full production. Ore production was primarily from mining the Chester vein systems serviced by the No. 10 shaft and the remnants of the Sunshine and Rambo vein stopes referred to as the Footwall area on the 3700 and 3400 levels. The 4000 and 4200 level Copper vein was under development from the No. 12 shaft.[6]

Sunshine Mine produced 18% of the Nation’s silver ore. By the end of 1988, the mine was at full production. Ore production was primarily from mining the Chester vein systems serviced by the No. 10 shaft and the remnants of the Sunshine and Rambo vein stopes referred to as the Footwall area on the 3700 and 3400 levels. The 4000 and 4200 level Copper vein was under development from the No. 12 shaft.[6]

(Photo [7] of plaque remember those that died in the fire)

Black Lung Disease

Key Facts

- Coal worker’s pneumoconiosis, or black lung, is one of over 200 types of pulmonary fibrosis and is classified as an interstitial lung disease. Your doctor may refer to your disease by any of these terms.

- An estimated 16% of coal workers are affected and after decades of improvement, the number of cases of black lung disease is on the rise again.

- There is no cure for coal worker’s pneumoconiosis, but treatment can help manage symptoms and improve quality of life.

- The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has safety standards to help workers employers and workers take steps to prevent black lung disease.

What Causes Coal Worker’s Pneumoconiosis?

Black lung disease can develop when coal dust is inhaled over a long period of time. Coal dust is made of dangerous carbon-containing particles that coal miners are at risk of inhaling, which is why it is mostly considered an occupational disease. Coal miners may also be exposed to silica-containing dust because coal mining may involve some drilling into silica-containing rock.

However, not all workers will develop the disease. Recent studies have found that about 16% of coal miners in the U.S. will contract the disease. This number has been increasing in recent years, which may be linked to changes in mining technology that allow for higher volumes of coal to be extracted in a given time period and changes in the mineral content of the coal that make it more hazardous. (Photo of a German Coal Miner in 1956 waiting for a shower[8])

How It Affects Your Body

When the coal dust is inhaled, the particles can travel through the airways all the way into the alveoli (air sacs) that are deep in the lungs. After the dust particles land and settle in the lung, lung tissue may try to get rid of the dust particles, causing inflammation as the body tries to fight the foreign particles. In some cases, the inflammation is severe enough to cause scar tissue to form. The damaging effects of the inhaled coal dust may not show up for many years, and many patients don’t develop symptoms until long after their initial exposure.

For coal worker’s pneumoconiosis, the scarring can be separated into two types: simple or complicated. In simple pneumoconiosis, a chest X-ray or CT scan will reveal small amounts of scar tissue, seen as tiny, circular nodules on the lungs. Complicated pneumoconiosis, also called progressive massive fibrosis, involves more severe scarring over a larger area of the lung tissue. In both types, your breathing will be negatively affected.

Symptoms of Coal Worker’s Pneumoconiosis

Symptoms of black lung disease can take years to develop. In early stages, the most common symptoms are cough, shortness of breath and chest tightness. Sometime the coughing may bring up black sputum (mucus). These symptoms may initially occur after strenuous activity, but as the disease progresses, they may become present at rest as well. If the scaring is severe, oxygen may be prevented from easily reaching the blood. This results in low blood oxygen levels which puts stress on other organs, such as the heart and brain, and can cause additional symptoms.

How Coal Worker’s Pneumoconiosis Is Diagnosed

There is no specific test for black lung disease. If you are concerned about your symptoms, your doctor will first want to take a detailed medical history, asking about your job history in detail to determine the likelihood of exposure. It may be a good idea to prepare the following information in advance:

- Your symptoms and the time they started

- Treatments given before for the symptoms and how they helped

- The work you have done over your entire career; the length of time you spent in each job; the nature of the work you performed.

- The products you were in contact with at work and whether or not you wore protective equipment

- Smoking history

- Any old medical records, including chest X-rays or CT scans

Your doctor will also want to perform a physical exam and breathing tests to measure your lungs’ ability to breathe and move oxygen. Imaging tests such as chest X-ray or CT scan may be suggested, to look for nodules and areas of inflammation. The Federal Mine Safety and Health Acts requires that surveillance programs be offered to all coal miners and include breathing tests and/or chest X-rays every year or periodically to look for abnormalities.[9]

Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders & Ergonomics

Once assessment and planning have been completed, including analysis of the collected data, the next step is implementing the strategies and interventions that will comprise the workplace health program. The intervention descriptions for Work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WMSD) include the public health evidence-base for each intervention, details on designing interventions related to Work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WMSD), and links to examples and resources.

Before implementing any interventions, the evaluation plan should also be developed. Potential baseline, process, health outcomes, and organizational change measures for these programs are listed under evaluation of WMSD prevention programs.

Musculoskeletal disorders (MSD) are injuries or disorders of the muscles, nerves, tendons, joints, cartilage, and spinal discs. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WMSD) are conditions in which:

- The work environment and performance of work contribute significantly to the condition; and/or

- The condition is made worse or persists longer due to work conditions1

In 1997, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) released a review of evidence for work-related MSDs. Examples of work conditions that may lead to WMSD include routine lifting of heavy objects, daily exposure to whole body vibration, routine overhead work, work with the neck in chronic flexion position, or performing repetitive forceful tasks. This report identified positive evidence for relationships between work conditions and MSDs of the neck, shoulder, elbow, hand and wrist, and back.1

The Bureau of Labor Statistics of the Department of Labor defines MSDs as musculoskeletal system and connective tissue diseases and disorders when the event or exposure leading to the case is bodily reaction (e.g., bending, climbing, crawling, reaching, twisting), overexertion, or repetitive motion. MSDs do not include disorders caused by slips, trips, falls, or similar incidents. Examples of MSDs include:

- Sprains, strains, and tears

- Back pain

- Carpal tunnel syndrome

- Hernia2

Musculoskeletal disorders are associated with high costs to employers such as absenteeism, lost productivity, and increased health care, disability, and worker’s compensation costs. MSD cases are more severe than the average nonfatal injury or illness.

- In 2001, MSDs involved a median of 8 days away from work compared with 6 days for all nonfatal injury and illness cases (e.g., hearing loss, occupational skin diseases such as dermatitis, eczema, or rash)2

- Three age groups (25–34 year olds, 35–44 year olds, and 45–54 year olds) accounted for 79% of cases2

- More male than female workers were affected, as were more white, non-Hispanic workers2

- Operators, fabricators, and laborers; and persons in technical, sales, and administrative support occupations accounted for 58% of the MSD cases3

- The manufacturing and services industry sectors together accounted for about half of all MSD cases2

- Musculoskeletal disorders account for nearly 70 million physician office visits in the United States annually, and an estimated 130 million total health care encounters including outpatient, hospital, and emergency room visits3

- In 1999, nearly 1 million people took time away from work to treat and recover from work-related musculoskeletal pain or impairment of function in the low back or upper extremities3

- The Institute in Medicine estimates the economic burden of WMSDs as measured by compensation costs, lost wages, and lost productivity, are between $45 and $54 billion annually3

- According to Liberty Mutual, the largest workers’ compensation insurance provider in the United States, overexertion injuries—lifting, pushing, pulling, holding, carrying or throwing an object—cost employers $13.4 billion every year3

Examples of common WMSDs are discussed below.

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS)

The U.S. Department of Labor defines CTS as a disorder associated with the peripheral nervous system, which includes nerves and ganglia located outside the spinal cord and brain. Carpal tunnel syndrome is the compression of the median nerve at the wrist, which may result in numbness, tingling, weakness, or muscle atrophy in the hand and fingers.4

- Carpel tunnel syndrome may affect as many as 1.9 million people, and 300,000 to 500,000 surgeries are performed each year to correct this condition4

- The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported 26,794 CTS cases involving days away from work in 2001, representing a median of 25 days away from work compared with 6 days for all nonfatal injury and illness cases. Most cases involved workers who were aged 25–54 (84%), female, and white, non-Hispanic (75%)4

- Two occupational groups accounted for more than 70% of all CTS cases in 2001: operators, fabricators, and laborers; and technical, sales, and administrative support4

Back injury and back pain

Back symptoms are among the top ten reasons for medical visits. For 5% to 10% of patients, the back pain becomes chronic.5-6

- In 2001, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported 372,683 back injury cases involving days away from work. Most cases involved workers who were aged 25–54 (79%), male (64%), and white, non-Hispanic (70%)7

- Two occupational groups accounted for more than 54% of back injury cases: operators, fabricators, and laborers (38%); and precision production, craft, and repair (17%)7

Data from scientific studies of primary and secondary interventions indicate that low back pain can be reduced by:

- Engineering controls (e.g., ergonomic workplace redesign)

- Administrative controls (specifically, adjusting work schedules and workloads)

- Programs designed to modify individual factors, such as employee exercise

- Combinations of these approaches

Arthritis

The term arthritis is used to describe more than 100 rheumatic diseases and conditions that affect joints, the tissues which surround the joint and other connective tissue. The pattern, severity and location of symptoms can vary depending on the specific form of the disease. Forty-six million Americans report that a doctor told them they have arthritis or other rheumatic conditions. Arthritis is the most common cause of disability in the United States.8 Arthritis limits the activities of nearly 19 million adults.9 Two thirds of individuals with arthritis are under age 65.10

The National Arthritis Data Working Group estimates that 27 million adults have osteoarthritis. Nine million adults report symptomatic knee osteoarthritis, and 13 million report symptomatic hand osteoarthritis. Persons are considered to have symptomatic osteoarthritis if they have frequent pain in a joint (e.g., pain in a joint on most days of a recent month) and radiographic (e.g., x-ray) evidence of osteoarthritis in that joint, although sometimes this pain may not actually emanate from the arthritis seen on the radiograph. Other forms of arthritis include rheumatoid arthritis and gout. Arthritis is a concern in the workplace both because it may develop from work-related conditions and because it may require worksite adaptations for employees with limitations or disabilities.11-12

Certain occupations are associated with increased prevalence of arthritis, specifically osteoarthritis, most often of the knee and/or hip. These occupations include mining, construction, agriculture, and sectors of the service industry.12-13 Common features of these occupations are physically demanding/heavy labor tasks, lifting or carrying heavy loads, exposure to vibration, high risk of joint or tissue injury, and prolonged periods of working in awkward or unnatural postures such as kneeling and crawling.

- In 2003, the total cost for arthritis conditions was $128 billion—$81 billion in direct costs and $47 billion in indirect costs14

- Persons who are limited in their work by arthritis are said to have Arthritis-attributable work limitations (AAWL). AAWL affects one in 20 working-age adults (aged 18-64) in the United States and one in three working-age adults with self-reported, doctor-diagnosed arthritis15

- The National Business Group on Health recommends that employers address arthritis by encouraging workers to avoid obesity and providing ergonomically appropriate workplace design16

Early diagnosis and appropriate management of arthritis can help people with arthritis decrease pain, improve function, stay productive, and lower health care costs. Appropriate management includes consulting with a doctor and self management education programs to help teach people with arthritis techniques to manage arthritis on a day-to-day basis. Physical activity and weight management programs are also important self-management activities for persons with arthritis.

Developing and Implementing Workplace Controls

Engineering controls, administrative controls and use of personal protective

A three-tier hierarchy of controls is widely accepted as an intervention strategy for reducing, eliminating, or controlling workplace hazards, including ergonomic hazards. The three tiers are:

- Use of engineering controls

- The preferred approach to prevent and control WMSDs is to design the job to take account of the capabilities and limitations of the workforce using engineering controls. Some examples include:

- Changing the way materials, parts, and products can be transported. For example, using mechanical assist devices to relieve heavy load lifting and carrying tasks or using handles or slotted hand holes in packages requiring manual handling

- Changing workstation layout, which might include using height-adjustable workbenches or locating tools and materials within short reaching distances

- The preferred approach to prevent and control WMSDs is to design the job to take account of the capabilities and limitations of the workforce using engineering controls. Some examples include:

- Use of administrative controls (changes in work practices and management policies)

- Administrative control strategies are policies and practices that reduce WMSD risk but they do not eliminate workplace hazards. Although engineering controls are preferred, administrative controls can be helpful as temporary measures until engineering controls can be implemented or when engineering controls are not technically feasible. Some examples include:

- Reducing shift length or limiting the amount of overtime

- Changes in job rules and procedures such as scheduling more breaks to allow for rest and recovery

- Rotating workers through jobs that are physically tiring

- Training in the recognition of risk factors for WMSDs and instructions in work practices and techniques that can ease the task demands or burden (e.g., stress and strain)

- Administrative control strategies are policies and practices that reduce WMSD risk but they do not eliminate workplace hazards. Although engineering controls are preferred, administrative controls can be helpful as temporary measures until engineering controls can be implemented or when engineering controls are not technically feasible. Some examples include:

- Use of personal protective equipment (PPE)

- PPE generally provides a barrier between the worker and hazard source. Respirators, ear plugs, safety goggles, chemical aprons, safety shoes, and hard hats are all examples of PPE

- Whether braces, wrist splints, back belts, and similar devices can be regarded as offering personal protection against ergonomic hazards remains an open question. Although these devices may, in some situations, reduce the duration, frequency or intensity of exposure, evidence of their effectiveness in injury reduction is inconclusive. In some instances, these devices may decrease one exposure but increase another because the worker has to “fight” the device to perform the work. An example is the use of wrist splints while engaging in work that requires wrist bending

Ergonomics

Ergonomics is the science of fitting workplace conditions and job demands to the capability of the working population.1 The goal of ergonomics is to reduce stress and eliminate injuries and disorders associated with the overuse of muscles, bad posture, and repeated tasks. A workplace ergonomics program can aim to prevent or control injuries and illnesses by eliminating or reducing worker exposure to WMSD risk factors using engineering and administrative controls. PPE is also used in some instances but it is the least effective workplace control to address ergonomic hazards. Risk factors include awkward postures, repetition, material handling, force, mechanical compression, vibration, temperature extremes, glare, inadequate lighting, and duration of exposure.17 For example, employees who spend many hours at a workstation may develop ergonomic-related problems resulting in musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs).[10]

- https://www.niehs.nih.gov/health/topics/science/toxicology/index.cfm ↵

- https://www.fda.gov/food/buy-store-serve-safe-food/food-irradiation-what-you-need-know ↵

- https://www.osha.gov/sites/default/files/publications/3439at-a-glance.pdf ↵

- http://trianglefire.ilr.cornell.edu/story/investigationTrial.html ↵

- https://live.staticflickr.com/2832/9379266623_e1a1cfd54c_b.jpg ↵

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sunshine_Mine ↵

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/oblomberg/9379267937/ ↵

- https://cdn1.titterfun.com/api/assets/image/odggks0nx2yv.jpg ↵

- https://www.lung.org/lung-health-diseases/lung-disease-lookup/black-lung/symptoms-diagnosis ↵

- https://www.cdc.gov/workplacehealthpromotion/health-strategies/musculoskeletal-disorders/index.html ↵