A materials recovery facility (MRF) is a key component of residential and commercial single-stream recycling programs. A MRF (often pronounced like it rhymes with “turf”) receives commingled materials and uses a combination of equipment and manual labor to separate and densify materials in preparation for shipment downstream to recyclers of the particular recovered materials.

What Is a Materials Recovery Facility?

Typical materials recovered at MRFs include ferrous metal, aluminum, glass, PET, HDPE, and mixed paper. There are two types of MRFs: clean, which handles the contents of commingled recycling bins that consist mostly of recyclable materials, and dirty, which handles solid waste that includes some salvageable recyclable materials.

Alternate names: material recovery facility, material(s) reclamation facility, material(s) recycling facility

How Does a Materials Recovery Facility Work?

MRFs can vary in some respects in terms of the technology employed; however, a typical process would involve the following steps.

MRFs have customer vehicle scales and a yard that can accommodate a queue of trucks. Incoming haulers arrive at the MRF and dump the commingled material onto the tipping floor. A front end loader or other bulk material handler then drops it into a large steel bin at the start of the processing line. This bin is known as the drum feeder. Inside of the drum feeder, a fast-moving drum meters out the commingled material onto the conveyor at a steady rate while also regulating the density of the material on the conveyor so that it is not packed too tightly together.

From there, material goes to a pre-sort station where workers standing along the conveyor spot and remove trash, plastic bags, or other inappropriately placed materials and separate them for disposition. Large pieces of plastic or steel, including pipes and other large items, can damage the system or expose workers to risk of injury.

A wet MRF is a special type of dirty MRF that uses water to help separate and clean materials.

Larger pieces of cardboard are removed from the mixed material stream, pushed to the top by large sorting disks turning on axles, while heavier material stays beneath. Smaller sets of sorting disks may then remove smaller pieces of paper. As materials are separated, they are diverted to separate conveyors for accumulation and baling.

Powerful magnets separate steel and tin containers, while an eddy current separator is used to draw aluminum cans and other non-ferrous metals from the remaining commingled material. Glass containers can be separated from plastic containers by a density blower, then hammered into the crushed glass known as cullet.

Any remaining plastic containers may be sorted manually by workers on the conveyor line, or optical sorters may be used to identify different materials and colors. Air classification may be used to separate key plastics such as HDPE and PET.

Separated materials, other than glass cullet, are typically baled. The weight of the finished bales vary greatly according to the material in question and the capacity of the baling equipment; finished bales can weigh anywhere from 25 to 1,500 pounds.

Clean MRFs vs. Dirty MRFs

A clean MRF can be differentiated from a dirty MRF in that it accepts commingled blue bin materials that contain mostly recyclables with some mistakenly included trash. A dirty MRF, on the other hand, processes household or commercial trash that most likely contains a low percentage of recyclables.

Dirty MRFs can capture recyclable materials that would have been missed because consumers or workers at a business placed it in the trash rather than in a blue bin. However, the dirty MRF can require considerably more manual labor for sorting and can result in the contamination of paper and old corrugated cardboard.

The recovery rate of recyclable material from a clean MRF is predictably very high, while the recovery rate from a dirty MRF is much lower, probably not more than 30%. Dirty MRF material is also much heavier, thanks to organic material in trash. It averages around 350 pounds per cubic yard when organics are not diverted, as opposed to 50 to 100 pounds per cubic yard of blue box material.

Problems for MRFs

Even clean MRFs struggle with a variety of unrecoverable materials, especially plastic bags. And a big problem for dirty MRFs are large, potentially hazardous objects, which must be removed at the beginning of processing.

Unwanted materials increase the need for manual sorting, which in turn increases inefficiencies for MRF operators and ultimately for the communities they serve. Such problems are intensified in the face of declining markets and lower prices for the materials they sell, such as has been experienced in recent years due to tightening import restrictions by China.

Key Takeaways

- A materials recovery facility receives commingled materials and separates out and bales the recyclables.

- MRFs typically recover ferrous metal, aluminum, glass, plastics, and mixed paper.

- Clean MRFs handle the contents of commingled recycling bins that consist mostly of recyclable materials.

- Dirty MRFs handle solid waste that includes some salvageable recyclable materials.[4]

Recycling

Executive Summary

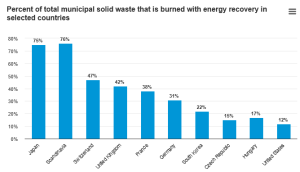

Garbage pickup is one of the core responsibilities and functions of many local governments. That service has been augmented, over the past four decades, by the collection of recyclables—typically paper, glass, metals, and plastic. Every major American city provides this service. Recycling has long been considered environmentally and financially beneficial. The materials would be reprocessed and used as newsprint, bottles, or cans, while the markets for such materials would make it possible to cover the costs of collection and reprocessing, or even to realize income. Even in periods of slack demand, the cost to dispose of recyclables was lower than that of mixed garbage—allowing cities to reap an economic benefit by paying less to get rid of some of their trash.

This apparent win-win situation has changed dramatically. China, which was importing several billion dollars’ worth of U.S. recyclables in 2017, announced a new policy, Operation National Sword, under which it would no longer permit the import of what it called “foreign trash.” The government stopped taking in other nations’ garbage partly because much of the material was not recyclable, and this was partly because of contamination. Pizza-box cardboard, for instance, is frequently contaminated by food residue, and plastic by dirty labels. As a result, much of the garbage that China imported was not recycled and ended up in landfills or incinerated. When Operation National Sword took effect in 2018, China insisted that it would accept only the noncontaminated recyclables that its manufacturers could use. As a result, the market for recyclables collapsed, and imports from the U.S. and elsewhere plunged.

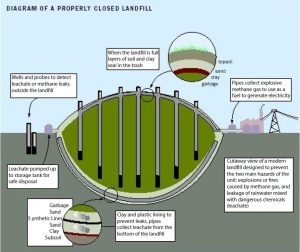

Since then, newspapers and other materials that municipal sanitation departments (or private firms) had picked up from city residents, who had dutifully sorted the materials and placed them in blue boxes, have increasingly piled up in warehouses or have been sent to landfills. Yet, despite their reputation, landfills—once infamous for leaking into groundwater—have become federally regulated and are far more environmentally safe. It remains true that recyclable materials may be reused—but there is no assurance that this will happen, especially for plastics.

Meanwhile, the economics of municipal recycling has been turned upside down. Those city departments responsible for trash pickup now incur significant costs, over and above what they would have to pay in the absence of recycling. These costs include the personnel and equipment for separate additional refuse collection (or payment to a contractor to provide the service), as well as the cost of paying firms to accept recyclables, now that they no longer can be profitably resold.

Some recyclables—notably, aluminum cans—continue to have a relatively high market value. But they are mixed with other materials that have little value and therefore require expensive sorting.

This paper examines the financial impact of separately collecting waste materials for recycling in five jurisdictions: New York City; Boston, Massachusetts; suburban Westchester County, New York; San Jose, California; and Dallas, Texas. It finds that the cost-benefit trade-off is unfavorable and that suspending or adjusting recycling services could lead to significant budget savings. These savings are particularly relevant in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, which is expected to reduce tax revenues and lead to pressure to reduce public services. Determining what is an essential public service in this context is crucial, and the costs of collecting and sorting recyclable materials—some materials may not even be recycled—risk crowding out appropriations for public safety, public health, parks, and schools.[1] This paper asks if the collection of recyclables should continue to be considered a core municipal service—or how it might be adjusted to be both environmentally beneficial and not an economic drain.[5]

Hazardous Waste and Superfund

Love Canal

Quite simply, Love Canal is one of the most appalling environmental tragedies in American history.

But that’s not the most disturbing fact.

What is worse is that it cannot be regarded as an isolated event. It could happen again–anywhere in this country–unless we move expeditiously to prevent it.

It is a cruel irony that Love Canal was originally meant to be a dream community. That vision belonged to the man for whom the three-block tract of land on the eastern edge of Niagara Falls, New York, was named–William T. Love.

Love felt that by digging a short canal between the upper and lower Niagara Rivers, power could be generated cheaply to fuel the industry and homes of his would-be model city.

But despite considerable backing, Love’s project was unable to endure the one-two punch of fluctuations in the economy and Nikola Tesla’s discovery of how to economically transmit electricity over great distances by means of an alternating current.

By 1910, the dream was shattered. All that was left to commemorate Love’s hope was a partial ditch where construction of the canal had begun.

In the 1920s the seeds of a genuine nightmare were planted. The canal was turned into a municipal and industrial chemical dumpsite.

Landfills can of course be an environmentally acceptable method of hazardous waste disposal, assuming they are properly sited, managed, and regulated. Love Canal will always remain a perfect historical example of how not to run such an operation.

In 1953, the Hooker Chemical Company, then the owners and operators of the property, covered the canal with earth and sold it to the city for one dollar.

It was a bad buy.

In the late ’50s, about 100 homes and a school were built at the site. Perhaps it wasn’t William T. Love’s model city, but it was a solid, working-class community. For a while.

On the first day of August, 1978, the lead paragraph of a front-page story in the New York Times read:

NIAGARA FALLS, N.Y.–Twenty five years after the Hooker Chemical Company stopped using the Love Canal here as an industrial dump, 82 different compounds, 11 of them suspected carcinogens, have been percolating upward through the soil, their drum containers rotting and leaching their contents into the backyards and basements of 100 homes and a public school built on the banks of the canal.

In an article prepared for the February, 1978 EPA Journal, I wrote, regarding chemical dumpsites in general, that “even though some of these landfills have been closed down, they may stand like ticking time bombs.” Just months later, Love Canal exploded.

The explosion was triggered by a record amount of rainfall. Shortly thereafter, the leaching began.

I visited the canal area at that time. Corroding waste-disposal drums could be seen breaking up through the grounds of backyards. Trees and gardens were turning black and dying. One entire swimming pool had been had been popped up from its foundation, afloat now on a small sea of chemicals. Puddles of noxious substances were pointed out to me by the residents. Some of these puddles were in their yards, some were in their basements, others yet were on the school grounds. Everywhere the air had a faint, choking smell. Children returned from play with burns on their hands and faces.

And then there were the birth defects. The New York State Health Department is continuing an investigation into a disturbingly high rate of miscarriages, along with five birth-defect cases detected thus far in the area.

I recall talking with the father of one the children with birth defects. “I heard someone from the press saying that there were only five cases of birth defects here,” he told me. “When you go back to your people at EPA, please don’t use the phrase ‘only five cases.’ People must realize that this is a tiny community. Five birth defect cases here is terrifying.”

A large percentage of people in Love Canal are also being closely observed because of detected high white-blood-cell counts, a possible precursor of leukemia.

When the citizens of Love Canal were finally evacuated from their homes and their neighborhood, pregnant women and infants were deliberately among the first to be taken out.

“We knew they put chemicals into the canal and filled it over,” said one woman, a long-time resident of the Canal area., “but we had no idea the chemicals would invade our homes. We’re worried sick about the grandchildren and their children.”

Two of this woman’s four grandchildren have birth defects. The children were born and raised in the Love Canal community. A granddaughter was born deaf with a cleft palate, an extra row of teeth, and slight retardation. A grandson was born with an eye defect.

Of the chemicals which comprise the brew seeping through the ground and into homes at Love Canal, one of the most prevalent is benzene — a known human carcinogen, and one detected in high concentrations. But the residents characterize things more simply.

“I’ve got this slop everywhere,” said another man who lives at Love Canal. His daughter also suffers from a congenital defect.

On August 7, New York Governor Hugh Carey announced to the residents of the Canal that the State Government would purchase the homes affected by chemicals.

On that same day, President Carter approved emergency financial aid for the Love Canal area (the first emergency funds ever to be approved for something other than a “natural” disaster), and the U.S. Senate approved a “sense of Congress” amendment saying that Federal aid should be forthcoming to relieve the serious environmental disaster which had occurred.

By the month’s end, 98 families had already been evacuated. Another 46 had found temporary housing. Soon after, all families would be gone from the most contaminated areas — a total of 221 families have moved or agreed to be moved.

State figures show more than 200 purchase offers for homes have been made, totaling nearly $7 million.

A plan is being set in motion now to implement technical procedures designed to meet the seemingly impossible job of detoxifying the Canal area. The plan calls for a trench system to drain chemicals from the Canal. It is a difficult procedure, and we are keeping our fingers crossed that it will yield some degree of success.

I have been very pleased with the high degree of cooperation in this case among local, State, and Federal governments, and with the swiftness by which the Congress and the President have acted to make funds available.

But this is not really where the story ends.

Quite the contrary.

We suspect that there are hundreds of such chemical dumpsites across this Nation.

Unlike Love Canal, few are situated so close to human settlements. But without a doubt, many of these old dumpsites are time bombs with burning fuses — their contents slowly leaching out. And the next victim cold be a water supply, or a sensitive wetland.

The presence of various types of toxic substances in our environment has become increasingly widespread — a fact that President Carter has called “one of the grimmest discoveries of the modern era.”

Chemical sales in the United States now exceed a mind-boggling $112 billion per year, with as many as 70,000 chemical substances in commerce.

Love Canal can now be added to a growing list of environmental disasters involving toxics, ranging from industrial workers stricken by nervous disorders and cancers to the discovery of toxic materials in the milk of nursing mothers.

Through the national environmental program it administers, the Environmental Protection Agency is attempting to draw a chain of Congressional acts around the toxics problem.

The Clean Air and Water Acts, the Safe Drinking Water Act, the Pesticide Act, the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, the Toxic Substances Control Act — each is an essential link.

Under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, EPA is making grants available to States to help them establish programs to assure the safe handling and disposal of hazardous wastes. As guidance for such programs, we are working to make sure that State inventories of industrial waste disposal sites include full assessments of any potential dangers created by these sites.

Also, EPA recently proposed a system to ensure that the more than 35 million tons of hazardous wastes produced in the U.S. each year, including most chemical wastes, are disposed of safely. Hazardous wastes will be controlled from point of generation to their ultimate disposal, and dangerous practices now resulting in serious threats to health and environment will not be allowed.

Although we are taking these aggressive strides to make sure that hazardous waste is safely managed, there remains the question of liability regarding accidents occurring from wastes disposed of previously. This is a missing link. But no doubt this question will be addressed effectively in the future.

Regarding the missing link of liability, if health-related dangers are detected, what are we as s people willing to spend to correct the situation? How much risk are we willing to accept? Who’s going to pick up the tab?

One of the chief problems we are up against is that ownership of these sites frequently shifts over the years, making liability difficult to determine in cases of an accident. And no secure mechanisms are in effect for determining such liability.

It is within our power to exercise intelligent and effective controls designed to significantly cut such environmental risks. A tragedy, unfortunately, has now called upon us to decide on the overall level of commitment we desire for defusing future Love Canals. And it is not forgotten that no one has paid more dearly already than the residents of Love Canal.[6]

his report summarizes a study of babies born sometime between 1960 and 1996 to women in the Love Canal Study Group. The results are part of the larger Love Canal Follow-up Health Study that was carried out by the New York State Department of Health.

About the Follow-up Health Study[7]

In 1996, the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) began gathering information for a comprehensive 20-year follow-up health study of Love Canal residents. The investigation and analysis are complete. The study (called the Love Canal Follow-up Health Study) is really four smaller studies:

- One focused on death rates and causes;

- One on cancer incidence; and,

- One measured and evaluated some Love Canal chemicals in the stored blood serum samples of a subgroup of the residents.

- This final part is an investigation of birth outcomes.

Each of the four studies is intended to stand alone and is based on information about the same group of Love Canal residents (called the Study Group). The four studies share common elements, including tracking who was living or who had died among the Study Group and estimating their likelihood of exposure to Canal chemicals. Other health problems were not evaluated due to the difficulty in getting comprehensive health data for former Love Canal residents.

About the Study Group (Cohort)

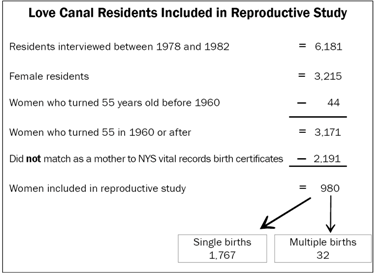

We traced a total of 6,181 Love Canal residents in the entire follow-up health study (see Figure 1 of the Background Community Report).

Included in the study were babies born between 1960 and 1996 to women:

- who were in the Study Group

- who lived in the Emergency Declaration Area (EDA) at Love Canal between 1940 and 1980 and

- and were interviewed between 1978 and 1982.

Their children were also included in the study.

The names of the 3,171 women from that group (who were between the ages of 12 and 55 from the years 1960 through 1996), were matched to birth certificates. We found that 980 mothers had 1,799 births (see Figure 1). Of these, 1,767 were single births and 32 were twins or other multiple births.

What We Did

As we did in the mortality and cancer studies, we compared:

- the information we obtained about people in the Study Group with information about people in Niagara County and the rest of New York State, not including New York City (Upstate NY).

- the data according to how close the mother lived to the Love Canal and during which time period she lived there. For some of the comparisons, we use the word “relocation”. For this study, relocation refers to the year:

- 1978 for people living in Tiers 1 or 2 at the time of interview; and

- 1980 for those living in Tiers 3 or 4 at the time of interview.

| Terms and Definitions | |

|---|---|

| Preterm | babies born before mother’s 37th week of pregnancy |

| Low Birth Weight | babies who weighed less than 5 pounds, 8 ounces at birth |

| Small for Gestational Age | babies whose weight was in the lowest 10% of all babies born in NYS for the length of time the mother was pregnant |

| Congenital Malformations Registry | NYSDOH’s collection of records for children in NYS who are diagnosed before they are two years old with a birth defect |

| Childhood Exposure | (for this study) mothers who lived in Tier 1 or 2 of the EDA before age 13, between 1954 and relocation |

We looked at five different reproductive outcomes:

- preterm births,

- the number of boys and girls,

- birth defects,

- low birth weight, and

- those that were small for the mothers’ length of pregnancy.

Information about birth outcomes, except for birth defects, was obtained from birth certificates.

What We Found

We did not find differences in patterns of birth outcomes for most mothers. The differences that we did find tended to be for babies born when the mother lived inside the EDA and to mothers who were potentially exposed when they were children.

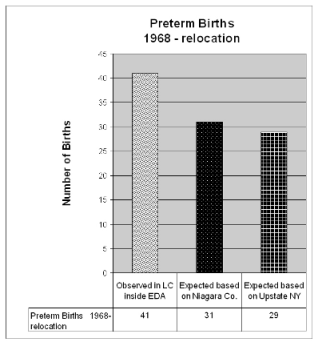

Preterm Births

Babies born premature or preterm were those born to mothers who were less than 37 weeks pregnant. How length of pregnancy was entered on birth certificates changed between 1967 and 1968. Because of this change, only information from 1968 and later was used for this part of the study. Also, only single births were used because twins or other multiple births are often born premature or small.

From 1968 until the time of relocation, women who were living inside the EDA had more preterm babies compared to other women in Upstate NY or Niagara County. This was not true for babies conceived in the same time period, when their mothers lived outside the EDA. Nor was it true for babies born between the time the women were relocated and 1996.

Number of Boys vs. Girls Born

Complete information about infant sex was available for the time period 1960-1996. All single and multiple births (see Figure 1) were included in comparing how many boys versus girls were born. Generally, about 105 boy babies are born for every 100 girl babies.

Love Canal women, who conceived before they relocated, tended to have more girl babies. Only 94 boy babies were born for every 100 girl babies. During the same time period, women who conceived after moving away from the EDA had about 105 boy babies for every 100 girl babies, similar to Upstate NY or Niagara County.

| Number of Boys vs. Girls Conceived before Relocation |

||

|---|---|---|

| Boys | Girls | |

| Observed in LC inside EDA | 317 | 337 |

| Expected based on NYS | 335 | 319 |

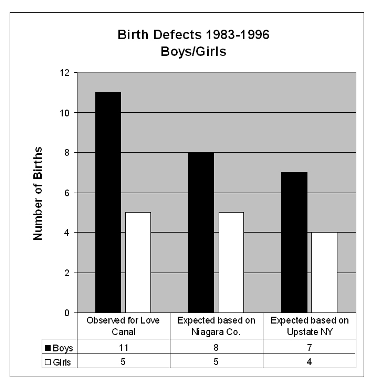

Birth Defects (congenital malformations)

Birth defects are reported to the New York State Congenital Malformations Registry (CMR). This registry collects data on birth defects diagnosed within the first two years of life among all children living in New York State. The first year of complete information collected by the CMR was 1983, so evaluation of birth defects was limited to births from 1983 until 1996, and all births, whether single or multiple, were included.

A total of 16 of the 492 children born between 1983 (beginning of reporting to the CMR) and 1996, were reported as having a birth defect. This was a slightly higher percentage than in Niagara County or Upstate NY. Eleven birth defects occurred among boys and five among girls. Because of the small number of birth defects, we cannot be certain that the results indicate a real difference or are due to chance.

Low Birth Weight and Small for Length of Pregnancy (gestational age)

Low birth weight babies weigh less than five pounds, eight ounces at birth. Babies small for the length of pregnancy (small for gestational age) weigh in the lowest 10% of all babies born in New York State after the same length of pregnancy. Like preterm births, only information for births from 1968 and later was used.

Overall, the number of babies who had low birth weights or who were small for the length of pregnancy was similar to others in New York State.

However, we also looked at outcomes for mothers who may have been exposed to Love Canal chemicals as children (childhood exposure) and who had children before relocating. For this study, childhood exposure for women meant living in Tiers 1 or 2 after 1954 and before the age of 13 (as described in the Background Community Report). These women tended to have:

- a low birth weight infant, compared to other Love Canal women;

- babies who were small for the mothers’ length of pregnancy; and,

- more girls than boys.

Comparison with Earlier Studies

Several studies of reproductive outcomes were done by other researchers in the past. These study findings are generally about the same as those from earlier Love Canal investigations of low birth weight and malformations. No other researcher has compared male to female births among Love Canal children. Some studies of other chemical exposures, however, do suggest that certain exposures may be connected with changes in the number of boy versus girl babies.

The Study and its Strengths and Weaknesses

As with most health studies, this study has some strong points as well as weaknesses.

Strengths

- We knew where and when the women in the Study Group lived at Love Canal, with 97% of the group having been traced.

- The potential for exposure varied, since the women lived in all areas of the EDA and lived there at many different ages.

- Two different groups were used to compare the Study Group:

- Upstate NY–whose rates of birth outcomes usually do not change much; and

- Niagara County–whose population is likely to be similar in many ways to women from Love Canal.

- The source of the information. We used New York State birth certificates and CMR for information about births.

Weaknesses

- The Study Group could only include adult women who took part in interviews conducted by the NYSDOH between 1978 and 1982 and their children under age 18.

- Information about smoking, alcohol use and occupation is known from the interview, but their use during the time of the woman’s pregnancy is unknown.

- It was impossible to make a complete list of people who lived at Love Canal between 1942 and 1980.

- Real estate records were not available

- Some people who lived in housing projects did not live there long.

- The father’s exposure to Love Canal chemicals may have been important, but getting information about fathers was difficult because it was not included on birth certificates. We surveyed male residents about their children during the study period, but not many men completed the survey.

- Births that occurred before the computerization of birth certificates in 1960 were not included.

- Because there is no national birth registry, if a woman moved out of New York and gave birth, we did not have that information.

- The study of birth defects was not possible until the CMR was created in 1983.

Conclusions

We did find an increase in preterm births and low birth weights for some of the analyses. We also found a suggestion of increases in congenital malformations in boys and fewer boys being born than usual compared to the number of girls. In general, these effects occurred when the baby was born or conceived when the mother was living in the EDA. Some of these effects seemed to occur more often if the mother lived in Tier 1 or 2 as a child and had the child before relocating.

Workplace Safety: OSHA and OSH Act Overview[8]

Created by FindLaw’s team of legal writers and editors | Last updated December 05, 2018

Employees have the right to a safe workplace free of known dangers to themselves and their co-workers. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) is the government agency in charge of setting standards, providing information and training to employees and employers, and generally making sure that America’s workforce stays healthy and safe.

Employee Rights Under OSHA and the OSH Act

The primary law covering worker safety is the Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) Act of 1970. The primary goal of this law is to reduce workplace hazards and implement safety and health programs for both employers and their employees. To this end, the OSH Act and related regulations from OSHA give employees a number of rights, including the rights to:

- get clear training and information in layman’s terms on the hazards of their workplace, ways to avoid harm, and applicable OSHA standards and laws;

- obtain and review documentation on work-related illnesses and injuries at the job site;

- confidentially make a complaint with OSHA to have an inspection of the workplace;

- if desired, accompany and take part in a requested OSHA inspection of the workplace;

- get copies of any tests done to measure workplace hazards (e.g. chemical, air, and similar testing);

- not be discriminated or retaliated against for making OSHA-related complaints or inquiries.

Supplementing these rights are a number of obligations and duties imposed on employers to maintain a safe work environment.

Employers’ Obligations Under the OSH Act

In addition to, or in connection with, the employee rights outlined above, under the OSH Act and OSHA guidelines, employers have the obligations to:

- first and foremost, provide a safe workplace free of serious hazards;

- find health and safety hazards;

- if hazards exist, eliminate or minimize them;

- if workplace hazards cannot be eliminated, provide employees with adequate safeguards and protective gear at no cost to them;

- notify employees of any hazards and provide the training necessary to address them;

- post a list of OSHA injuries and citations, plus the OSHA poster in a place where employees will see them;

- maintain records of work-related injuries.

Workplace Hazards and OSHA Inspections

If an employer is not addressing a workplace hazard that has been brought to its attention, an employee should contact an OSHA area office or state office via a written complaint. As noted above, there are ways to do this anonymously, even though the law prohibits employers from discriminating or retaliating against safety whistleblowers. Once the report is made, OSHA or its state counterpart will determine whether or not there are reasonable grounds for believing that a violation or danger exists. If so, the agency at issue will conduct an inspection and report its findings to the employer and employee representatives, including any steps that need to be taken to correct safety and health issues.

HAZWOPER 40-hour is required for workers that perform activities that expose or potentially expose them to hazardous substances.

This course is specifically designed for workers who are involved in clean-up operations, voluntary clean-up operations, emergency response operations, and storage, disposal, or treatment of hazardous substances or uncontrolled hazardous waste sites.

Topics include protection against hazardous chemicals, elimination of hazardous chemicals, safety of workers and the environment and OSHA regulations. This course covers topics included in 29 CFR 1910.120.

Please note that 8 hours of hands-on training is required for the 40 hour Hazwoper course and can be completed by a qualified instructor. The three days field experience under a trained, experienced supervisor is the responsibility of the student’s employer or potential employer.[9]

HAZWOPER 24-hour is required for employees visiting an Uncontrolled Hazardous Waste Operation mandated by the Government. This course fulfills your requirements for certification under 29 CFR, Part 1910.120 (q), or other applicable state regulations for certification to the 24-hour Occasional Site Worker level.

This course covers broad issues pertaining to the hazard recognition at work sites. OSHA has developed the HAZWOPER program to protect the workers working at hazardous sites and devised extensive regulations to ensure their safety and health. This course, while identifying different types of hazards, also suggests possible precautions and protective measures to reduce or eliminate hazards at the work place.

Workers must have 24 hours of initial training and one day of supervised field experience before they are allowed to enter the site.

The online course meets the standard requirement of 24 hours of initial training. The one day field experience under a trained, experienced supervisor is the responsibility of the student’s employer or potential employer.[10]

HAZWOPER 8-hour Annual Refresher

OSHA developed the HAZWOPER program to keep workers safe at hazardous sites. These extensive regulations ensure worker health and safety when followed. Our HAZWOPER courses comply with all OSHA regulations.[11]

Superfund: CERCLA Overview

The Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA), commonly known as Superfund, was enacted by Congress on December 11, 1980. This law created a tax on the chemical and petroleum industries and provided broad Federal authority to respond directly to releases or threatened releases of hazardous substances that may endanger public health or the environment. Over five years, $1.6 billion was collected and the tax went to a trust fund for cleaning up abandoned or uncontrolled hazardous waste sites. The Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980 (CERCLA):

- established prohibitions and requirements concerning closed and abandoned hazardous waste sites;

- provided for liability of persons responsible for releases of hazardous waste at these sites; and

- established a trust fund to provide for cleanup when no responsible party could be identified.

The law authorizes two kinds of response actions:

- Short-term removals, where actions may be taken to address releases or threatened releases requiring prompt response.

- Long-term remedial response actions, that permanently and significantly reduce the dangers associated with releases or threats of releases of hazardous substances that are serious, but not immediately life threatening. These actions can be conducted only at sites listed on EPA’s National Priorities List .

CERCLA also enabled the revision of the National Contingency Plan (NCP). The NCP provided the guidelines and procedures needed to respond to releases and threatened releases of hazardous substances, pollutants, or contaminants. The NCP also established the National Priorities List.[12]

What is a Hazardous Waste?

Simply defined, a hazardous waste is a waste with properties that make it dangerous or capable of having a harmful effect on human health or the environment. Hazardous waste is generated from many sources, ranging from industrial manufacturing process wastes to batteries and may come in many forms, including liquids, solids gases, and sludges.

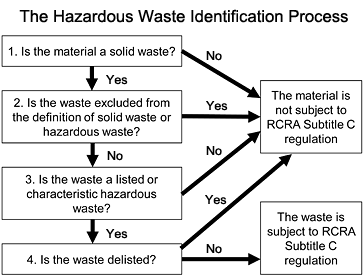

EPA developed a regulatory definition and process that identifies specific substances known to be hazardous and provides objective criteria for including other materials in the regulated hazardous waste universe. This identification process can be very complex, so EPA encourages generators of wastes to approach the issue using the series of questions described below:

identification process for more information.

In order for a material to be classified as a hazardous waste, it must first be a solid waste. Therefore, the first step in the hazardous waste identification process is determining if a material is a solid waste.

The second step in this process examines whether or not the waste is specifically excluded from regulation as a solid or hazardous waste.

Once a generator determines that their waste meets the definition of a solid waste, they investigate whether or not the waste is a listed or characteristic hazardous waste. Finally, it is important to note that some facilities petitioned EPA to delist their wastes from RCRA Subtitle C regulation. You can research the facilities that successfully petitioned EPA for a delisting in Appendix IX of Title 40 of the Code of Federal Regulations part 261.

EPA’s Cradle-to-Grave Hazardous Waste Management Program

In the mid-twentieth century, solid waste management issues rose to new heights of public concern in many areas of the United States because of increasing solid waste generation, shrinking disposal capacity, rising disposal costs, and public opposition to the siting of new disposal facilities. These solid waste management challenges continue today, as many communities are struggling to develop cost-effective, environmentally protective solutions. The growing amount of waste generated has made it increasingly important for solid waste management officials to develop strategies to manage wastes safely and cost effectively.

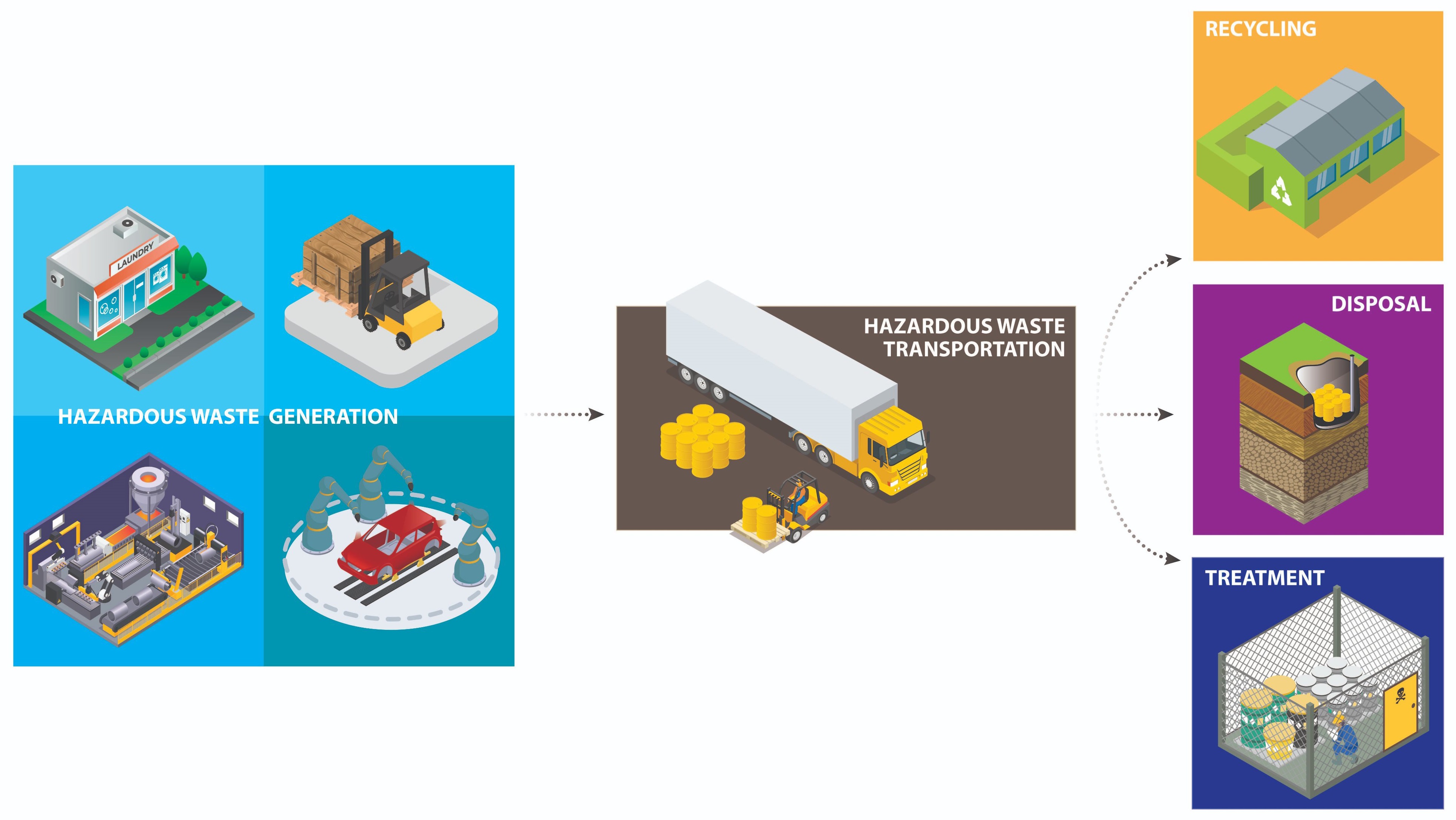

RCRA set up a framework for the proper management of hazardous waste. From this authority, EPA established a comprehensive regulatory program to ensure that hazardous waste is managed safely from “cradle to grave” meaning from the time it is created, while it is transported, treated, and stored, and until it is disposed:

Hazardous Waste Generation

Under RCRA, hazardous waste generators are the first link in the hazardous waste management system. All generators must determine if their waste is hazardous and must oversee the ultimate fate of the waste. Furthermore, generators must ensure and fully document that the hazardous waste that they produce is properly identified, managed, and treated prior to recycling or disposal. The degree of regulation that applies to each generator depends on the amount of waste that a generator produces.

Hazardous Waste Transportation

After generators produce a hazardous waste, transporters may move the waste to a facility that can recycle, treat, store or dispose of the waste. Since such transporters are moving regulated wastes on public roads, highways, rails and waterways, United States Department of Transportation hazardous materials regulations, as well as EPA’s hazardous waste regulations, apply.

Hazardous Waste Recycling, Treatment, Storage and Disposal

To the extent possible, EPA tried to develop hazardous waste regulations that balance the conservation of resources, while ensuring the protection of human health and environment. Many hazardous wastes can be recycled safely and effectively, while other wastes will be treated and disposed of in landfills or incinerators.

Recycling hazardous waste has a variety of benefits including reducing the consumption of raw materials and the volume of waste materials that must be treated and disposed. However, improper storage of those materials might cause spills, leaks, fires, and contamination of soil and drinking water. To encourage hazardous waste recycling while protecting health and the environment, EPA developed regulations to ensure recycling would be performed in a safe manner.

Treatment Storage and Disposal Facilities (TSDFs) provide temporary storage and final treatment or disposal for hazardous wastes. Since they manage large volumes of waste and conduct activities that may present a higher degree of risk, TSDFs are stringently regulated. The TSDF requirements establish generic facility management standards, specific provisions governing hazardous waste management units and additional precautions designed to protect soil, ground water and air resources.

Comprehensive information on the final steps in EPA’s hazardous waste management program is available online, including Web pages and resources related to:

Regulations for Specific Wastes EPA has tried, to the extent possible, to develop regulations for hazardous waste management that provide adequate protection of human health and the environment while at the same time:

- fostering environmentally sound recycling and conservation of resources,

- making the rules easier to understand,

- facilitating better compliance, or

- providing flexibility in how certain hazardous waste is managed.

Thus, EPA created alternative management standards, exclusions and exemptions for certain types of wastes including:

- Academic Laboratory Wastes

- Cathode Ray Tubes (CRTs)

- Household Hazardous Waste

- Mixed Radiological Wastes

- Pharmaceutical hazardous wastes

- Solvent-Contaminated Wipes

- Universal Waste

- Used Oil[13]