Health Impact Assessment

Health impact assessment (HIA) is used to evaluate the public health consequences of proposed decisions in non-health sectors. HIA is a systematic process that uses an array of data sources and analytic methods and considers input from stakeholders to determine the potential effects of a proposed policy, plan, program, or project on the health of a population and whether the health effects are distributed evenly within the population. HIAs provide practical recommendations for how to minimize negative health effects and maximize beneficial health effects. [Source: National Academies Press]

HIA should be distinguished from other health assessment methodologies, described below, that can be used during or after an HIA.

Community Health Assessment

A community health assessment, or community health needs assessment, is a systematic examination of the health status indicators for a given population that is used to identify key problems and assets in a community. The ultimate goal of a community health assessment is to develop strategies to address the community’s health needs and identified issues. Community health assessment is a prerequisite for tribal, state, local, or territorial public health departments seeking voluntary accreditation. A variety of tools and processes may be used to conduct a community health assessment; the essential ingredients are community engagement and collaborative participation. [Source: Public Health Accreditation Board]

Data obtained on health status and community health needs and assets during a community health assessment can be used in an HIA to describe the existing health status of the affected population.

Cost-Benefit Analysis

Cost-benefit analysis is a type of economic evaluation that measures both costs and benefits (i.e., negative and positive consequences) associated with an intervention in dollar terms.

Because HIA typically does not examine the costs associated with its recommended strategies to promote health and mitigate adverse health impacts, a cost-benefit analysis could be conducted to help decide which HIA recommendations are the most feasible. For more information, see CDC’s Introduction to Prevention Effectiveness.

Environmental Impact Assessment

Environmental impact assessment (EIA) is the process of identifying, predicting, evaluating and mitigating the biophysical, social, and other relevant effects of proposed developments prior to major decisions being made. EIAs are currently a requirement in most countries. [Source: International Association of Impact Assessment]

In the United States, the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) requires federal agencies to integrate environmental values into their decision-making processes by considering the environmental impacts of their proposed actions and reasonable alternatives to those actions. To meet NEPA requirements, federal agencies first prepare an environmental assessment (EA) to determine whether a more thorough environmental impact statement (EIS) is needed. For more information on NEPA, visit the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency website.

NEPA requires consideration and analysis of health effects of specified federal agency actions within the EIA process. Although NEPA does not refer to HIA as a separate requirement, HIA can be an appropriate way to meet statutory requirements for health effects analysis when conducted within the context of an interdisciplinary EIA.

Bhatia and Wernham (2008) reviewed the purpose and procedures of EIA, existing regulatory requirements for health effects analysis, and potential barriers to and opportunities for improving integration of human health concerns within the EIA process. The authors suggested that EIA might be an unrealized opportunity for improving environmental health and justice.

Human Health Risk Assessment

A human health risk assessment is a quantitative, analytic process to estimate the nature and risk of adverse human health effects associated with exposure to specific chemical contaminants or other hazards in the environment, now or in the future. For more information, see the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency website.

Human health risk assessments are not comprehensive and tend to focus on biophysical risks from exposure to hazardous substances. Results from a human health risk assessment can be used within an HIA to predict human health effects of specific exposures.

Public Health Assessment

The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) developed the public health assessment process for evaluating the public health implications of exposures to environmental contamination. A public health assessment is formally defined as “The evaluation of data and information on the release of hazardous substances into the environment in order to assess any past, current, or future impact on public health, develop health advisories or other recommendations, and identify studies or actions needed to evaluate and mitigate or prevent human health effects” [Source: 42 Code of Federal Regulations, Part 90]. See the ATSDR Public Health Assessment Guidance Manual for more information.

An Important Assessment Tool

HIA is a useful tool to assess how a proposed decision will affect the health of a population and whether vulnerable populations are more likely to be impacted [or whether the health impacts are distributed evenly within the population]. The goal of HIA is to provide recommendations during the decision-making process that will protect health and reduce health inequities. Below are examples of how HIA has been recommended as an important assessment tool.

CDC cosponsored the 2011 National Research Council report Improving Health in the United States: The Role of Health Impact Assessment, which found that the HIA holds promise for incorporating aspects of health into decision making because of its

- Applicability to a broad array of policies, programs, plans, and projects.

- Consideration of adverse and beneficial health effects.

- Ability to consider and incorporate various types of evidence.

- Engagement of communities and stakeholders in a deliberative process.

Elements of a Health Impact Assessment3 Elements of a Health Impact Assessment." National Research Council. 2011. Improving Health in the United States: The Role of Health Impact Assessment. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/13229

Chapter 2 established the rationale for examining the potential effects of decisions on health and health disparities and highlighted health impact assessment (HIA) as a potential tool for assessing the health implications of various decisions. This chapter describes the types, structure, and content of HIAs and summarizes the HIA process, methodologic approaches, and variations in practice. It is informed by a review of U.S. and international HIA literature and guidelines (see Appendixes A and E) and by the experience of committee members and others who provided input during the committee process. On the basis of its review, the committee synthesized the information from guidance, practice, and literature to propose criteria that define an HIA and draw several conclusions regarding HIA practice. As discussed in this chapter, HIAs have been used for a wide variety of applications and at all levels of government (local, state, tribal, and federal) and have been conducted with varied resources over different schedules. The committee does not intend that the definition and criteria proposed in this chapter be considered rigid requirements but rather that they reflect an ideal of practice, deviation from which may occur but should be based on clear and well-articulated needs and rationale.

Before discussing the various elements of HIA, it is important to understand the context in which HIA is undertaken in the United States. As described in Appendix A, there are few laws in the United States that specifically require HIA, although many—such as the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA)—require a consideration of health that can be accomplished through HIA. Most HIAs in the United States are therefore undertaken outside the formal decision-making process by organizations (such as nonprofit community-based groups), universities, or health departments that do not have decision-making authority over the proposals being addressed. Although less common to date, HIAs are also sometimes conducted by a decision-making agency, such as a metropolitan planning organization or a federal agency complying with NEPA. The decision to initiate an HIA is often made ad hoc when public-health advocates recognize that the proposal may have important health implications that would not otherwise be recognized or addressed. There are often not clear lines of authority between the team conducting the HIA and the decision-maker. The health effects that are included, the data sources and methods that are used, and the recommendations that are made are therefore determined by the HIA practitioners rather than according to a legal or regulatory standard (Wernham 2011). Thus, the assessment phase is separated from the management phase, as recommended elsewhere (NRC 1983). The fact, however, that the team conducting the HIA is aware of the decision context allows the assessment to be decision-relevant.

CATEGORIES OF HEALTH IMPACT ASSESSMENT

Scholars point to a remarkable consistency in the basic elements that are generally included in descriptions of HIA (Mindell et al. 2008). In practice, however, there is some inconsistency in how HIAs are conducted—for example, how stakeholders are engaged and how data are collected and analyzed—and in the structure and content of the final work products of an HIA. The diversity of practice owes partly to the fact that HIAs are undertaken for a wide array of policy-making that spans many sectors, levels of government, types of proposal (policies, plans, programs, and projects), and degrees of complexity. The variability in the practice has evolved in the absence of widely accepted practice standards or formal regulatory or procedural requirements for HIA outside NEPA and related state laws (see Appendix A). However, it appears to be increasingly accepted that HIA is carried out to inform the decision rather than to evaluate the impacts after the decision is made, and there is general agreement on the procedural steps of HIA (Harris-Roxas and Harris 2011).

HIA practice is often defined in terms of several categories. According to effort, complexity, and duration, HIAs are often described as rapid, intermediate, or comprehensive. Rapid HIAs may be completed in a short time (weeks to months), are often focused on smaller and less complex proposals, and generally involve primarily literature review and descriptive or qualitative analysis. The phrase desktop HIA has also been used to refer to a rapid HIA that entails little or no public engagement. Another variation, rapid-appraisal HIA, has been described and in some texts includes explicit public engagement through an initial half-day workshop for stakeholders (Parry and Stevens 2001; Mindell et al. 2003; ICMM 2010). Intermediate HIAs require more time and resources and involve more complex pathways, more stakeholder engagement, and a more detailed analysis but include little collection of new data. Comprehensive HIAs are most commonly differentiated from rapid and intermediate HIAs by the scope of potential impacts and the need for collection of new primary data. They can take longer than a year to complete.

HIAs are also differentiated according to whether they are integrated into an environmental impact assessment or done independently. Another categorization is based on the breadth of the HIA and distinguishes HIAs that have a tight focus—such as ones that use a narrow definition of health and emphasize quantification—from HIAs that have a broader, holistic focus shaped by the social determinants of health (Kemm 2001). Others have proposed categorizing HIAs as participatory (emphasizing shared governance, public participation, and a focus on socioeconomic and environmental determinants), quantitative or analytic (concentrating on the methods and rigor of the analysis), or procedural (drawing on elements of the other two approaches but emphasizing the procedural steps required and often undertaken within a specified administrative or regulatory context) (Cole and Fielding 2007).

In practice, the categories are rarely used consistently, and a single HIA often encompasses a blend of various approaches to stakeholder engagement and participation, analytic methods, and interactions with the formal decision-making process. For example, desktop HIAs may consider indirect stakeholder input through review of public comments submitted outside the HIA process, comprehensive HIAs may have relatively little stakeholder engagement, and rapid-appraisal HIAs of smaller-scale proposals may involve collection of some new data to inform the analysis. The various categories of HIAs, although useful for describing distinct themes in the field, do not necessarily represent consistently distinct strains of practice. Instead, it appears that the specific methods and approaches used in a single HIA often evolve within the basic framework described above and develop as a pragmatic response to context. Influences on practice include the timeline, resources and skills available to the HIA team, the factors being considered and the data available for analysis, and the legal and regulatory context of the decision-making process. That description is consistent with the earlier characterizations of HIA as a combination of procedures, methods, and tools (WHO 1999; Quigley et al. 2006).

The committee notes that the diversity of approaches and decision contexts imposes challenges for determining the resources required for conducting an HIA. For example, although rapid HIAs are small-scale, low-cost investigations, comprehensive HIAs that require new primary data collection can take longer than a year to complete and require substantially more resources. Information on costs of HIAs would be valuable in determining whether an HIA can be undertaken with the resources available and could inform the screening process as described below. However, the committee notes that no published studies in the United States have attempted to quantify the costs of undertaking an HIA across a variety of settings. Such information would be useful for informing future implementation.

DEFINITION OF HEALTH IMPACT ASSESSMENT

The committee proposes on the basis of its review the following adaptation of the current working definition of the International Association of Impact Assessment (Quigley et al. 2006) as a technical definition of HIA:

HIA is a systematic process that uses an array of data sources and analytic methods and considers input from stakeholders to determine the potential effects of a proposed policy, plan, program, or project on the health of a population and the distribution of the effects within the population. HIA provides recommendations on monitoring and managing those effects.

That definition reflects the committee’s finding that the involvement of stakeholders—although the approaches used vary from little or no involvement to robust engagement and participation at every step—has consistently been described as a core element of HIA practice and should be considered essential to it. Although rapid or desktop HIAs may not involve stakeholders or consider their input, this often (although not uniformly) reflects a pragmatic response to limitations, such as the timeframe for the decision or resources available to the HIA team, rather than an optimal practice. The definition also notes that recommendations should incorporate monitoring, which is essential for effective continuing management as a decision is implemented.

WHO CONDUCTS HEALTH IMPACT ASSESSMENTS?

HIAs can be conducted by a variety of agencies, organizations, or individuals. A decision-making body—such as a department of planning or transportation—can conduct an HIA to inform its own decision. It is also common for local, state, or tribal health departments to undertake an HIA to inform another agency’s decision-making. University researchers have conducted HIAs, and community-based organizations have conducted HIAs with technical assistance from public-health experts to inform officials who are deliberating on a legislative or administrative proposal. HIAs are also done by private consultants who are hired by a project proponent or decision-maker or by private-industry stakeholders.

Because the assessment of health effects depends on an in-depth understanding of changes that may affect health—such as changes in traffic flow, roadway design, air quality, or community revenue sources—HIAs are inherently multidisciplinary; public-health experts may lead the effort but must draw on resources and expertise from other disciplines. Thus, HIA teams may include not only health experts but professionals in other related disciplines, such as air or water quality or traffic modeling. As discussed in greater depth in the section on scoping, it is common to convene advisory or steering committees, which can include both technical and policy experts and representatives from stakeholder groups that have an interest in the decision outcome.

The training and credentials of HIA practitioners are variable, and there is no universally accepted standard for a level of training necessary to lead an HIA. In the United States, HIAs have commonly been undertaken by people who have an MPH or equivalent degree and have attended a brief (2- to 5-day) training

session. In this report, HIA practitioner refers to the person (or people) involved in conducting an HIA.

PROCESS FOR HEALTH IMPACT ASSESSMENT

The tasks or elements that are described as part of an HIA are fairly consistent in the peer-reviewed literature and guides reviewed by the committee. The grouping of the elements in discrete stages or steps of an HIA is less consistent; some guides list as few as five steps, and others describe as many as nine (Quigley et al. 2006; Bhatia 2010; ICMM 2010). The committee selected a six-step framework as a clear way to organize and describe the critical elements of an HIA. The steps can be described as follows:

(1) Screening determines whether a proposal is likely to have health effects and whether the HIA will provide information useful to the stakeholders and decision-makers.

(2) Scoping establishes the scope of health effects that will be included in the HIA, the populations affected, the HIA team, sources of data, methods to be used, and alternatives to be considered.

(3) Assessment involves a two-step process that first describes the baseline health status of the affected population and then assesses potential impacts.

(4) Recommendations suggest design alternatives that could be implemented to improve health or actions that could be taken to manage the health effects, if any, that are identified.

(5) Reporting documents and presents the findings and recommendations to stakeholders and decision-makers.

(6) Monitoring and evaluation are variably grouped and described. Monitoring can include monitoring of the adoption and implementation of HIA recommendations or monitoring of changes in health or health determinants. Evaluation can address the process, impact, or outcomes of an HIA.

The following sections provide an overview of the process of conducting an HIA. For each step, the committee describes the basic purpose, objectives, and practice elements; summarizes the main outputs; and presents conclusions regarding pertinent issues raised. Major issues and challenges for HIA development and practice are considered in Chapter 4. The reader will notice that some of the committee’s descriptions and characterizations overlap with those of other guides; the similarities highlight the consistencies in the field.

Screening

Screening establishes the need for and value of conducting an HIA. Because HIAs can address decisions that range from small, localized programs or projects to national policies, screening ensures that HIA is used judiciously and when it is most likely to be valuable. Given the volume and breadth of decisions at the local, state, tribal, and federal levels that can potentially affect health in some way, one of the challenges for HIA practice is to determine which proposals to screen. In the absence of mandates or formal procedures, topics for screening are often chosen on the basis of the interests of a group wishing to use HIA as opposed to a structured, strategic selection process.1

More structured approaches have also been used. In some cases, collaboration between a health department and other agencies has resulted in the identification of appropriate proposals for screening. In other cases, all proposals in selected agencies or sectors have been screened by local governments (SFCC 1998; Lester et al. 1999; Roscam Abbing 2004). For example, the San Francisco Department of Public Health routinely screens major projects and plans to ensure adequate analysis and mitigation of environmental health impacts. In Alaska, all large natural-resources development proposals are now screened for the need for HIA in a new program begun by the state health department.

Screening involves making an initial rapid judgment of whether an HIA is likely to be feasible and valuable. The central considerations include whether the proposal in question might cause important changes in health, whether health is already a major focus of the decision-making process, whether the legal framework provides an opportunity for health to be factored into the decision, and whether data, staff, resources, and time are adequate to complete a successful HIA in time to provide useful input into the decision-making process (that is, can information be provided within the timeline for the decision). Another consideration is whether the proposal is likely to place a disproportionate burden of risk on vulnerable populations in the affected community; screening proposals on this basis helps to ensure that the HIA addresses the risk factors that underlie observed disparities in the rates of illness among various populations.

A variety of screening tools and algorithms are commonly used (Cole et al. 2005; PHAC 2005; Harris et al. 2007; Bhatia 2010). Some use pertinent screening questions, such as the ones noted, and apply a sequential yes-no query to each (Cole et al. 2005). Some provide a checklist of factors to consider and often focus on health determinants that might be affected by the proposal. Some decisions to conduct HIA may depend on a specific statutory requirement or mandated procedure. For example, in the context of NEPA, the lead federal agency must consider “the degree to which the proposed action affects public health or safety” to determine whether a proposal is likely to have “significant” effects and therefore require an environmental impact statement (40 CFR 1508.27). Ultimately, regardless of the specific tool used, the decision to conduct HIA in most cases relies on the practitioner’s or decision-maker’s judgment regarding the likelihood of impacts, the time and resources available, and the likelihood that the information produced by the HIA will be a valuable aid to decision-making.

1Under NEPA, a federal agency must determine whether a federal environmental decision is likely to have significant effects, and if so, the level of analysis required (40 C.F.R. Section 1508.27). Because the degree to which the proposed action affects public health or safety is one factor considered, this process could be considered the equivalent of the screening step of an HIA. In practice, however, explicit consideration of health has been rare (Steinemann 2000; Cole et al. 2004; Bhatia and Wernham 2008).

Because any actions taken on the basis of HIA recommendations need to be implemented within a specific legal and policy context, screening needs to establish a clear description of the decision-making process and context. It should also identify the points at which there is an opportunity for information from the HIA to influence decisions. Mapping out the timeline for the decision-making process can be helpful, and for large and complex programs and projects, identifying the agencies involved and their jurisdictions is important. Such programs and projects involve many agencies and entities that have authority over some aspect of planning and implementation. For example, the planning of the Atlanta Beltline, as described later in this chapter, involved the regional planning commission, local legislative bodies, state and federal environmental regulators, and private developers. It is also useful to assess the political context of the proposal to be assessed and consider, for example, the major political drivers of the proposal, the arguments made by political supporters and those opposed to the proposal, and any economic or technical constraints that limit the alternatives that can be considered.

Public concerns are a common trigger for a decision to screen, and the degree of concern or controversy about a proposal may be one of the factors weighed in the decision to undertake an HIA. For example, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health responded to citizen concerns regarding a proposed power plant by considering whether HIA would be an appropriate way to address them (McAuliffe 2009). The committee notes that public involvement is important in screening; information provided by stakeholders may provide insight into the potential effects of a proposal under consideration that contribute to the final determination of whether an HIA is warranted and likely to be useful.

Screening is often not well documented, and it is often not clear from an HIA report what factors were considered in making the decision to do an HIA. Moreover, because there is generally no written record of HIAs that stop at screening, still less is known about the reasons that have led to decisions not to proceed with HIA. Box 3-1 provides an example of how screening on a proposal for a residential housing program was conducted. It includes the information that was taken into account and the final output of the screening process, which was a decision on whether to commission and proceed with an HIA.

Outputs of Screening

Screening should result in a simple statement that includes the following:

• A description of the proposed policy, program, plan, or project that will be the focus of the HIA, including the timeline for the decision and intervention points at which HIA information will be used.

• A statement of why the proposal was selected for screening.

• A preliminary opinion regarding the potential importance of the proposal for health.

• The expected resource requirements of the HIA and the ability of the HIA team to meet them.

• A description of the political and policy context of the decision and an analysis of the opportunities to influence decision-making or otherwise make health-oriented changes.

BOX 3-1 Screening: HIA of a Residential Housing Program

The Crossings is a proposed housing development in Los Angeles that will provide 450 units in a newly rezoned residential area that needs affordable housing. A local community-based organization worked with a housing developer on the proposal and site plan. They expressed “interest in developing The Crossings in a way that will address local community needs for affordable housing and for other community assets that are safe, healthy, and supportive” (p. Intro-1).

In 2009, an HIA was conducted to ensure that health impacts were considered in the design and development of The Crossings and in the broader policies that affected redevelopment in the area. The HIA report describes the screening process but does not provide great detail about it.

The HIA notes that the area within which The Crossings is proposed to be built has the following characteristics:

• A growing population of families that have children.

• Dilapidated housing conditions.

• Prevalence of overcrowding.

• A lack of access to needed goods and services.

The HIA notes that the residential area is inhabited by a vulnerable population, that the built environment is of low quality, that the development will potentially have important health implications for residents in the local and surrounding communities, and that there is a strong commitment shown by the community and the developer to integrate health considerations into the planning process. It was concluded during the screening phase that an HIA would add value to project outcomes. An HIA would identify health assets, health liabilities, and health-promoting mitigations related to the proposed development project. The facts that resources were available and that timelines were appropriate were also relevant to the decision to conduct an HIA.

• A screening recommendation—for example, no further action required; no HIA, but health advice and input to be offered in an alternative way; or proceed with HIA.

Committee Conclusions Regarding Screening

Screening is essential for high-quality HIA. Poorly selected proposals may result in HIAs that add little new information and consume considerable time and resources of the HIA team to complete and of recipients to review. HIA should not be assumed to be the best approach to every health-policy question but should instead be seen as part of a spectrum of public-health and policy-oriented approaches, some of which will be more appropriate than others, depending on the specific application. Although the reasons and objectives for HIA are often not articulated at the outset of screening, establishing well-defined objectives will focus the screening process on determining whether HIA is likely to be an effective approach for achieving them.

Any approach to determining which proposals will be screened should demonstrate a consistent rationale; should document the rationale in the HIA report; and should take account of public input. Screening should also consider whether a proposal conforms with applicable standards, policies, or laws relevant to health inasmuch as there is a wide variety of them that bear directly or indirectly on health. For example, U.S. priorities for improving public health are expressed in the Healthy People 2020 Program of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS 2010). Some laws—such as NEPA, state environmental-policy acts, and various local zoning ordinances—may establish protection of health as a requirement or priority. The programs and policies, however, may not provide any guidance on how health should be considered (see, for example, Pub. L 91-190, 42 U.S.C. 4321-4347 [1970]; EC 2001). Furthermore, some policies may focus on determinants of health—for example, economic development, transportation, or housing—rather than explicitly mentioning health. In each case, it is important to determine how the standards, policies, programs, and laws bear on how health is factored into a proposal.

The committee concludes that the following are the most important factors to consider in determining whether to do an HIA:

• The potential for substantial adverse or beneficial health effects and the potential to make changes in the proposal that could result in an improved health risk-benefit profile.

• The potential for HIA-based information to alter a decision or help a decision-maker discriminate among decision options.

• The potential for irreversible or catastrophic effects (including effects of low likelihood).

• The potential for health effects to place a disproportionate burden on or substantially benefit vulnerable populations.

• Public concern or controversy regarding health effects of the proposed decision.

• The opportunity to bring health information into a decision-making process that may otherwise not include this information.

• The potential for the HIA to be completed in the time allotted and with the resources available.

Ultimately, the HIA report should provide a rational and consistent explanation of how proposals are selected for screening. That explanation is particularly important when public funds are to be used for an HIA because the public may want to understand the basis for allocating sparse public resources. Given the breadth of decisions that are likely to warrant consideration, the approach taken will vary on the basis of who is initiating the HIA, the capacity and authority of the agency or entity undertaking it, and the objectives for contemplating an HIA.

Scoping

Scoping establishes the boundaries of the HIA and identifies the health effects to be evaluated, the populations affected, the HIA team, sources of data, methods to be used, and any alternatives to be assessed. Well-executed scoping saves time, work, and resources in the later stages of the HIA (Harris et al. 2007). The choice of what to evaluate will reflect the specific social, political, and policy context of the decision; the needs, interests, and questions of stakeholders and decision-makers; and the health status of the affected population.

Potential Health Effects

Determining the potential health effects to include in the HIA and proposing hypothetical causal pathways are the central tasks of scoping. Scoping considers input from many sources, including preliminary literature searches, public input, and professional or expert opinion in fields relevant to the proposal. Because it will often not be practical or possible to address all direct and indirect health effects that appear theoretically possible, it is important to select issues carefully.2 Setting priorities considers pathways that appear most important from a public-health perspective and considers issues that have been raised prominently by stakeholders. Questions that are important from a public-health perspective might include the severity of the health effect, the size and likelihood of the effect, and the potential of the effect to exacerbate health disparities. In practice, some HIAs have focused on a specific health end point, such as obesity, or health concerns related to a single impact of the proposal, such as the health effects of air pollutants, most likely without using a systematic approach that considered and eliminated other impacts (see, for example, Kuo et al. 2009; Castro et al. 2010).

Iteration during scoping and between scoping and assessment often results in additional changes in the final list of issues included in the HIA. During scoping, the HIA team may produce an initial list, refine it on the basis of stakeholder input, and then make it final through research and analysis in the assessment phase. In other cases, the initial scope is generated by stakeholders and then refined through research and input from advisory or steering committees.

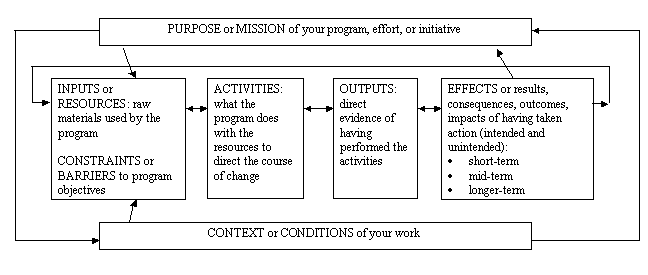

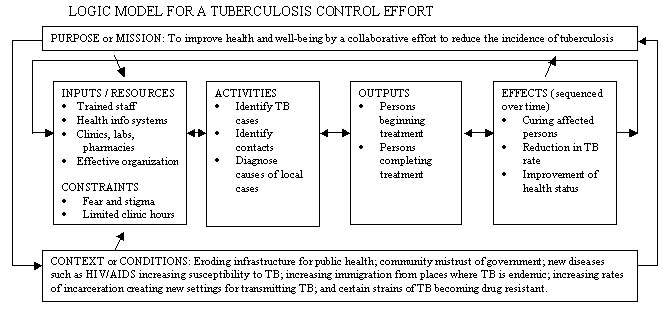

Several approaches for scoping are available. One approach uses a logic framework that maps out the causal pathways by which health effects might occur (see Figure 3-1). In general, this approach describes effects directly related to the proposal (such as changes in air emissions) and traces them to health determinants (such as air quality) and finally to health outcomes (such as asthma). The first step in the framework is typically a determinant of health, such as air pollution, traffic, employment, or noise. Logic frameworks can be used as part of stakeholder engagement to develop a shared understanding of how a project will develop and the outcomes that can be expected (Cave and Curtis 2001a,b; Cave et al. 2001). Another method of scoping is to develop a table that facilitates a systematic and rapid appraisal of all the potential ways in which a proposal might affect health (see Table 3-1). In this approach, the aspects of a proposal that may affect health are listed and considered in major categories of health and illness.

Box 3-2 provides an example of scoping for the HIA of a proposed development in Atlanta. The health issues were identified by determining the populations that would be affected and then considering how they would be affected. A variety of information was used to inform the process

Establishing Who Might Be Affected

Scoping identifies those likely to be affected by the proposed policy, project, program, or plan. The process may include identifying communities and geographic regions; demographic, economic, racial, and ethnic groups; and vulnerable populations, such as children, elderly people, disabled people, low-income people, racial and ethnic minorities, and people who have pre-existing health conditions. The process of describing pre-existing health issues, health disparities, and influences on health may also begin during scoping, although the full characterization of baseline health status generally takes place during assessment.

FIGURE 3-1 Example of a logic framework that maps out the possible causal pathways by which health effects might occur. Source: SFDPH 2011.

TABLE 3-1 Example of a Table Used for Systematic Scoping

Potentially Affected Areas Health Category

Chronic Disease Infectious Disease Injury Nutrition Well-being or Psychosocial

Environment

• Air quality

• Water quality

• Soil

• Other

Economy

• Personal (income, employment; can include occupational risk)

• Revenue or expense to local, state, or tribal government (support for or drain on services, infrastructure)

Infrastructure

• Need for new roads and transit, water, or sanitation systems

• Demand on existing infrastructure

Services

• New services as a direct result of proposal

• Drain on existing services resulting from proposed action

Demographics

• Community composition

• Traffic volume

• Residential or commercial use patterns

Other

BOX 3-2 Scoping: Atlanta BeltLine HIA

As described by Ross (2007, p. 9), “the Atlanta BeltLine is a transit, trails, parks, and redevelopment project that uses a 22-mile loop of largely abandoned freight rail line that lies between two and four miles from the city center” and affects about 45 neighborhoods. In 2005, an HIA was conducted by a multidisciplinary team. The goal was to incorporate health considerations into the decision-making process “by predicting health consequences, informing decision makers and the public about health impacts, and providing realistic recommendations to prevent or mitigate negative health outcomes” (p. 9).

One of the first steps in identifying the parameters of the assessment was to establish an understanding of the BeltLine, a complex project that had been evolving for several years and was expected to be constructed over a 30-year period. The HIA team needed an authoritative description on which to base its assessment. The Atlanta Development Authority’s BeltLine Redevelopment Plan (November 2005) was identified as a coherent and publicly accepted vision that had been approved by local elected officials (ADA 2005). The source of public funding for the project was the Tax Allocation District (TAD), and only within the district’s boundaries could funding be collected and bond money spent. A variety of planning and zoning, funding, and environmental regulatory decisions were required for the BeltLine’s various components to be developed.

The HIA team was assisted by an advisory committee, but it appears that the committee was not involved in the scoping. The HIA report states that scoping was done by the HIA team and involved desk-based research and a web and postal survey. The scoping phase was used to identify the parameters of the assessment, the affected and most vulnerable populations, and potential key health effects. The final HIA report describes each factor (see below) and presents the results of the scoping. The entire decision-making process is appropriately not described in the final report; however, the reader is not told whether the HIA team prepared a scoping report or whether it presented the findings of the scoping stage.

Affected populations: As the TAD constituted only a portion of the city that would be directly affected, the HIA team created the HIA study area by placing a 0.5-mile buffer around the BeltLine TAD. The HIA study area was divided into five planning areas, and census (2000) and mortality data were used to analyze the population profiles. Variations were found in race, age, employment status, poverty, car ownership, and mortality. It was not possible to derive mortality rates for demographic subgroups. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System data were used for the county and the state and stratified by race.

Most vulnerable populations: Less information was provided about this step. The most vulnerable populations were identified as people of low economic status, children, older adults, renters, and the carless. Calculations were conducted to develop a vulnerability score. The top 10% of the census tracts within the study area were then identified as locations of the most vulnerable populations.

Key health effects: Issues were identified through analysis of newspaper coverage; outreach to such groups as local officials, members of the public, and businesses; development of a logic framework; and a survey of people living, working, or attending school near the BeltLine. The HIA team identified the following critical issues that could affect the health of the study area population: access and social equity, physical activity, safety, social capital, and environment (including air quality, noise, and water management). Source: Adapted from Ross 2007.

The HIA Team, Advisory Bodies, and Stakeholder Involvement

Scoping also determines who will be part of the HIA team and establishes a plan for technical oversight and review, stakeholder participation and involvement, and involvement of and interaction with decision-makers. Commonly, a core team is responsible for the bulk of writing and analysis. In some cases, the team may draw on outside consultants who have expertise in a specific health issue or method. Furthermore, HIA teams commonly rely on analyses by such experts as traffic-safety engineers or air-quality analysts who provide information on the links between the proposal and changes in health determinants.

Advisory, steering, and technical oversight committees are also commonly convened during scoping. Membership is variable but may include representatives of affected communities or community-based organizations, industrial proponents or business groups, public-health experts, officials involved in the decision-making process, and others who have a stake in the outcome. The committees may be convened for several purposes, including providing technical guidance or peer review, ensuring adequate and fair representation of diverse interests and priorities among stakeholders, communicating the results of the HIA to decision-makers, and developing recommendations that address community needs and are compatible with the specific legal requirements of the decision-making process.

Public and stakeholder participation during scoping can serve several important purposes, such as providing local knowledge regarding existing conditions and potential impacts, introducing alternatives or mitigation measures that stakeholders would endorse as effective ways to address key concerns, and allowing representative participation in shaping the terms of the HIA by groups affected by the proposal. Scoping also establishes a plan for stakeholder participation in later phases of the HIA. The early and central role of stakeholder identification and participation is analogous to the guidance provided in the report published by the Presidential/Congressional Commission on Risk Assessment and Risk Management (1997).

The approaches taken for stakeholder involvement vary widely. The variation partly reflects the wide array of applications of HIA; for example, it is not necessary or feasible to use the same approaches to involve stakeholders for a local project and for a high-level state or national policy. That issue is discussed at greater length in Chapter 4.

Data Sources and Methods

Scoping identifies appropriate data sources for the analysis and should also identify important data gaps. In some cases, the timeline and available resources will prevent collection of new data to address gaps that are identified. In others, scoping may identify studies that can be carried out by the HIA team or studies that can be carried out by experts involved in some other aspect of the planning, permitting, or review process (such as air-quality or traffic-safety analysis). Scoping also establishes a plan for the analytic methods that will be used during the assessment phase. The specific methods used in assessment are discussed in depth in the next section.

Alternatives

Another issue that should be addressed in scoping is identifying alternatives to the proposed action. The cornerstone of an assessment that is conducted to comply with NEPA is the presentation of a set of reasonable alternatives to the proposed action; the assessment then considers the impacts of the proposed action and the alternatives. Assessing alternatives in parallel with the proposal can aid decision-making by highlighting tradeoffs and actions that can be taken to achieve the desired outcome while minimizing harms. Because HIA in the United States is often undertaken outside a formal legal mandate, it has not consistently included alternatives assessment. The committee concludes that when alternatives to the proposal being assessed are under consideration, the HIA team should assess the impacts of each alternative. Because developing an alternative (such as suggesting an alternate route for a proposed highway) involves many considerations that may be outside the purview and expertise of an HIA team, the committee recognizes that it may not be practical to expect the HIA team to develop alternatives independently. However, where practical, the HIA team should aim to evaluate a variety of alternatives or, minimally, to identify the characteristics of proposed actions that would be health-protective or detrimental to health. For example, although an HIA may not be able to incorporate engineering or economic specifications for alternate routes for a proposed highway, it could discuss factors that would influence health outcomes, such as indicating that a desirable route would be, for example, 100 m from any school or elderly facility or would not be proximate to high-population-density areas with a number of vulnerable people. It would then fall to the decision-makers to determine routes that met those criteria.

Outputs of Scoping

On the basis of its review of current guidance and practice, the committee recommends that scoping should result in a framework for the HIA and a written project plan that includes the following:

• An initial brief summary of the pathways through which health could be affected and the health effects to be addressed, including a rationale for how the effects were chosen and an account of any potential health effects that were considered but were not selected and why. Any logic models or scoping tables that were completed should also be included.

• Identification of the population and vulnerable groups—such as children, the elderly, racial or ethnic minorities, low-income people, and communities—that are likely to be affected.

• A description of the research questions, data sources, methods to be used, and any alternatives to be assessed.

• Identification of apparent data gaps and of data collection that could be undertaken to address the gaps or a rationale for not undertaking data collection.

• A summary of how stakeholders were engaged, the main issues that the stakeholders raised, and how they will be addressed or why they will not be addressed.

Committee Conclusions Regarding Scoping

The credibility and relevance of HIA to the decision-making process rest on a balanced and complete examination of the health risks, benefits, and tradeoffs presented by the project, policy, program, or plan being assessed. For that reason, it is important that scoping begin with a systematic consideration of all potential effects rather than limiting consideration to a subset of issues predetermined by the team’s research interests or regulatory requirements. Conversely, to have the greatest relevance as an informational and planning document and to ensure judicious use of resources, the HIA should ultimately focus on the health effects of greatest potential importance. Therefore, scoping should be thought of as a two-part process that starts with a systematic effort to identify all potentially important effects and that continues with selection of the most important and well-substantiated effects for further analysis at later stages.

Characteristics unique to the affected community may not be obvious to HIA practitioners who are outside the community. Stakeholders, however, may have insights into local conditions and potential solutions for addressing concerns raised by the proposal under consideration. Scoping should therefore entail a deliberative process that involves engagement of stakeholders. Review of literature and a consideration of the social, economic, and political context of the eventual decision are also important. In selecting the analytic methods that will be used, the HIA practitioner should consider not only technical limitations but what type of information will be most useful to decision-makers.

Finally, it is appropriate to include issues that are the subject of community concern even if they seem unlikely to be substantiated by further analysis. An HIA does not have to accept community concern uncritically. If the HIA is based on a thorough analysis, provides complete information so that community members are able to critique the analysis, and is conducted openly, it may provide reassurance to affected communities even if the conclusions do not support the community’s concerns.