6 Multiple Intelligences

Now that we’ve begun to understand the higher cognitive domains you need to work within to demonstrate college-level learning, let’s think about all of the different kinds of intelligence you can use to make this demonstration of learning. Just like a university campus has many buildings housing fields as different as dance, astrophysics, education, art history, psychology, and more, the human brain has many different areas which each require a different kind of intelligence.

While a college student may spend more time in one particular building, like for their major classes, that doesn’t mean that they aren’t also capable of or interested in things going on in other buildings. Our brains do the same thing: we may spend most of our time thinking about one major preoccupation, such as our job, but we have many other intelligences that we use as well.

All of these intelligences are important for demonstrating your prior learning. Let’s take a few moments to examine multiple intelligences and how you can incorporate them into your prior learning portfolio.

Classifying Intelligence

What exactly is intelligence? The way that researchers have defined the concept of intelligence has been modified many times since the birth of psychology. British psychologist Charles Spearman believed intelligence consisted of one general factor, called g, which could be measured and compared among individuals. Spearman focused on the commonalities among various intellectual abilities and demphasized what made each unique. Long before modern psychology developed, however, ancient philosophers, such as Aristotle, held a similar view (Cianciolo & Sternberg, 2004).

Others psychologists believe that instead of a single factor, intelligence is a collection of distinct abilities. In the 1940s, Raymond Cattell proposed a theory of intelligence that divided general intelligence into two components: crystallized intelligence and fluid intelligence (Cattell, 1963). Crystallized intelligence is characterized as acquired knowledge and the ability to retrieve it. When you learn, remember, and recall information, you are using crystallized intelligence. You use crystallized intelligence all the time in your coursework by demonstrating that you have mastered the information covered in the course. Fluid intelligence encompasses the ability to see complex relationships and solve problems. Navigating your way home after being detoured onto an unfamiliar route because of road construction would draw upon your fluid intelligence. Fluid intelligence helps you tackle complex, abstract challenges in your daily life, whereas crystallized intelligence helps you overcome concrete, straightforward problems (Cattell, 1963).

Other theorists and psychologists believe that intelligence should be defined in more practical terms. For example, what types of behaviors help you get ahead in life? Which skills promote success? Think about this for a moment. Being able to recite all 44 presidents of the United States in order is an excellent party trick, but will knowing this make you a better person?

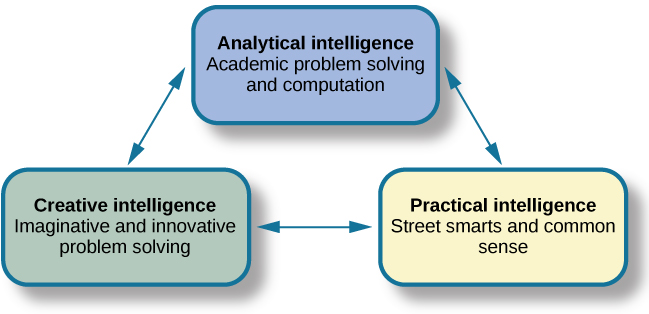

Robert Sternberg developed another theory of intelligence, which he titled the triarchic theory of intelligence because it sees intelligence as comprised of three parts (Sternberg, 1988): practical, creative, and analytical intelligence.

Practical intelligence, as proposed by Sternberg, is sometimes compared to “street smarts.” Being practical means you find solutions that work in your everyday life by applying knowledge based on your experiences. This type of intelligence appears to be separate from traditional understanding of IQ; individuals who score high in practical intelligence may or may not have comparable scores in creative and analytical intelligence (Sternberg, 1988).

Analytical intelligence is closely aligned with academic problem solving and computations. Sternberg says that analytical intelligence is demonstrated by an ability to analyze, evaluate, judge, compare, and contrast. When reading a classic novel for literature class, for example, it is usually necessary to compare the motives of the main characters of the book or analyze the historical context of the story. In a science course such as anatomy, you must study the processes by which the body uses various minerals in different human systems. In developing an understanding of this topic, you are using analytical intelligence. When solving a challenging math problem, you would apply analytical intelligence to analyze different aspects of the problem and then solve it section by section.

Creative intelligence is marked by inventing or imagining a solution to a problem or situation. Creativity in this realm can include finding a novel solution to an unexpected problem or producing a beautiful work of art or a well-developed short story. Imagine for a moment that you are camping in the woods with some friends and realize that you’ve forgotten your camp coffee pot. The person in your group who figures out a way to successfully brew coffee for everyone would be credited as having higher creative intelligence.

Multiple Intelligences Theory was developed by Howard Gardner, a Harvard psychologist and former student of Erik Erikson. Gardner’s theory, which has been refined for more than 30 years, is a more recent development among theories of intelligence. In Gardner’s theory, each person possesses at least eight intelligences. Among these eight intelligences, a person typically excels in some and falters in others (Gardner, 1983). Table describes each type of intelligence.

| Intelligence Type | Characteristics | Representative Career |

|---|---|---|

| Linguistic intelligence | Perceives different functions of language, different sounds and meanings of words, may easily learn multiple languages | Journalist, novelist, poet, teacher |

| Logical-mathematical intelligence | Capable of seeing numerical patterns, strong ability to use reason and logic | Scientist, mathematician |

| Musical intelligence | Understands and appreciates rhythm, pitch, and tone; may play multiple instruments or perform as a vocalist | Composer, performer |

| Bodily kinesthetic intelligence | High ability to control the movements of the body and use the body to perform various physical tasks | Dancer, athlete, athletic coach, yoga instructor |

| Spatial intelligence | Ability to perceive the relationship between objects and how they move in space | Choreographer, sculptor, architect, aviator, sailor |

| Interpersonal intelligence | Ability to understand and be sensitive to the various emotional states of others | Counselor, social worker, salesperson |

| Intrapersonal intelligence | Ability to access personal feelings and motivations, and use them to direct behavior and reach personal goals | Key component of personal success over time |

| Naturalist intelligence | High capacity to appreciate the natural world and interact with the species within it | Biologist, ecologist, environmentalist |

Gardner’s theory is relatively new and needs additional research to better establish empirical support. At the same time, his ideas challenge the traditional idea of intelligence to include a wider variety of abilities, although it has been suggested that Gardner simply relabeled what other theorists called “cognitive styles” as “intelligences” (Morgan, 1996). Furthermore, developing traditional measures of Gardner’s intelligences is extremely difficult (Furnham, 2009; Gardner & Moran, 2006; Klein, 1997).

Emotional Intelligence

Gardner’s inter- and intrapersonal intelligences are often combined into a single type: emotional intelligence. Emotional intelligence encompasses the ability to understand the emotions of yourself and others, show empathy, understand social relationships and cues, and regulate your own emotions and respond in culturally appropriate ways (Parker, Saklofske, & Stough, 2009). People with high emotional intelligence typically have well-developed social skills. Some researchers, including Daniel Goleman, the author of Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More than IQ, argue that emotional intelligence is a better predictor of success than traditional intelligence (Goleman, 1995). However, emotional intelligence has been widely debated, with researchers pointing out inconsistencies in how it is defined and described, as well as questioning results of studies on a subject that is difficulty to measure and study emperically (Locke, 2005; Mayer, Salovey, & Caruso, 2004)

Intelligence can also have different meanings and values in different cultures. If you live on a small island, where most people get their food by fishing from boats, it would be important to know how to fish and how to repair a boat. If you were an exceptional angler, your peers would probably consider you intelligent. If you were also skilled at repairing boats, your intelligence might be known across the whole island. Think about your own family’s culture. What values are important for Latino families? Italian families? In Irish families, hospitality and telling an entertaining story are marks of the culture. If you are a skilled storyteller, other members of Irish culture are likely to consider you intelligent.

Some cultures place a high value on working together as a collective. In these cultures, the importance of the group supersedes the importance of individual achievement. When you visit such a culture, how well you relate to the values of that culture exemplifies your cultural intelligence, sometimes referred to as cultural competence.

Creativity

Creativity is the ability to generate, create, or discover new ideas, solutions, and possibilities. Very creative people often have intense knowledge about something, work on it for years, look at novel solutions, seek out the advice and help of other experts, and take risks. Although creativity is often associated with the arts, it is actually a vital form of intelligence that drives people in many disciplines to discover something new. Creativity can be found in every area of life, from the way you decorate your residence to a new way of understanding how a cell works.

Creativity is often assessed as a function of one’s ability to engage in divergent thinking. Divergent thinking can be described as thinking “outside the box;” it allows an individual to arrive at unique, multiple solutions to a given problem. In contrast, convergent thinking describes the ability to provide a correct or well-established answer or solution to a problem (Cropley, 2006; Gilford, 1967)

Summary

Intelligence is a complex characteristic of cognition. Many theories have been developed to explain what intelligence is and how it works. Sternberg generated his triarchic theory of intelligence, whereas Gardner posits that intelligence is comprised of many factors. Still others focus on the importance of emotional intelligence. Finally, creativity seems to be a facet of intelligence, but it is extremely difficult to measure objectively.

Attribution:

This chapter contains material taken from “What are Intelligence and Creativity?” by Rice University and licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

References:

Cattell, R. (1963). Theory of fluid and crystallized intelligence: A critical experiment. Journal of Educational Psychology, 54(1), 1–22.

Cianciolo, A. T., & Sternberg, R. J. (2004). Intelligence: A brief history. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Cropley, A. (2006). In praise of convergent thinking. Creativity Research Journal, 18(3), 391–404.

Furnham, A. (2009). The validity of a new, self-report measure of multiple intelligence. Current Psychology: A Journal for Diverse Perspectives on Diverse Psychological Issues, 28, 225–239.

Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. New York: Basic Books.

Gardner, H., & Moran, S. (2006). The science of multiple intelligences theory: A response to Lynn Waterhouse. Educational Psychologist, 41, 227–232.

Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence; Why it can matter more than IQ. New York: Bantam Books.

Guilford, J. P. (1967). The nature of human intelligence. New York, NY: McGraw Hill.

Klein, P. D. (1997). Multiplying the problems of intelligence by eight: A critique of Gardner’s theory. Canadian Journal of Education, 22, 377-94.

Locke, E. A. (2005, April 14). Why emotional intelligence is an invalid concept. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26, 425–431.

Mayer, J. D., Salovey, P., & Caruso, D. (2004). Emotional intelligence: Theory, findings, and implications, Psychological Inquiry, 15(3), 197–215.

Morgan, H. (1996). An analysis of Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligence. Roeper Review: A Journal on Gifted Education, 18, 263–269.

Parker, J. D., Saklofske, D. H., & Stough, C. (Eds.). (2009). Assessing emotional intelligence: Theory, research, and applications. New York: Springer.

Sternberg, R. J. (1988). The triarchic mind: A new theory of intelligence. New York: Viking-Penguin.