5.1: Understanding Small Groups

Learning Objectives

- Define small group communication.

- Identify characteristics of small groups

- Explain the functions of small groups.

- Compare and contrast different types of small groups.

- Explain the advantages and disadvantages of small groups.

Many of the communication skills you are learning are directed toward dyadic communication, meaning they are applied in two-person interactions. While many of these skills can be transferred to and used in small group contexts, the more complex nature of group interaction necessitates some adaptation and some additional skills. Small group communication refers to interactions among three or more people who are connected through a common purpose, mutual influence, and a shared identity. In this section, we will learn about small group characteristics, functions, and types.

Size of Small Groups

The ideal small group has no set number of members. A small group requires a minimum of three people (because two people would be a pair or dyad), but the upper range of group size is contingent on the purpose of the group. When groups grow beyond fifteen to twenty members, it becomes difficult to consider them a small group based on the previous definition. An analysis of the number of unique connections between members of small groups shows that they are deceptively complex. For example, there are fifteen separate potential dyadic connections within a six-person group, and a twelve-person group would have sixty-six potential dyadic connections (Hargie, 2011). As you can see, when we double the number of group members, we more than double the number of connections, which shows that network connection points in small groups grow exponentially as membership increases. So, while there is no set upper limit on the number of group members, it makes sense that the number of group members should be limited to those necessary to accomplish the goal or serve the purpose of the group. Small groups that add too many members increase the potential for group members to feel overwhelmed or disconnected.

Structure of Small Groups

Internal and external influences affect a group’s structure. In terms of internal influences, member characteristics play a role in initial group formation. For instance, a person who is well informed about the group’s task and/or highly motivated as a group member may emerge as a leader and set into motion internal decision-making processes, such as recruiting new members or assigning group roles, that affect the structure of a group (Ellis & Fisher, 1994). Different members will also gravitate toward different roles within the group and advocate for certain procedures and courses of action. External factors such as group size, task, and resources also affect group structure. Some groups will have more control over these external factors through decision-making than others. For example, a commission that is put together by a legislative body to look into ethical violations in athletic organizations will likely have less control over its external factors than a self-created weekly book club.

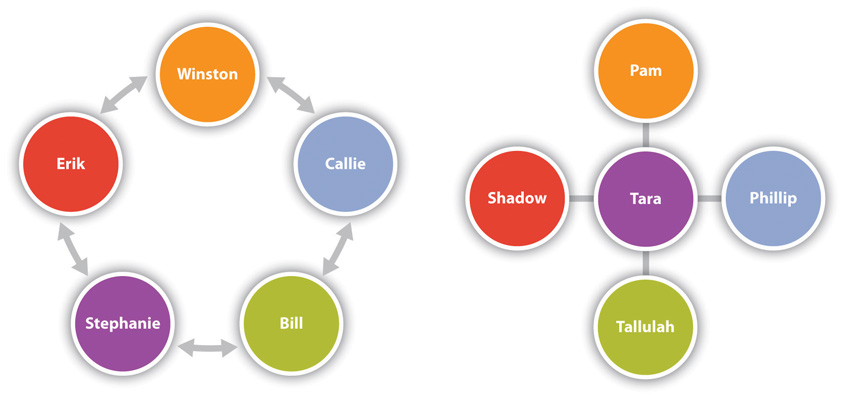

Size and structure also affect communication within a group (Ellis & Fisher, 1994). In terms of size, the more people in a group, the more issues with scheduling and coordination of communication. Remember that time is an important resource in most group interactions and a resource that is usually strained. The structure can increase or decrease the flow of communication. Reachability refers to how one member is or isn’t connected to other group members. For example, the “Circle” group structure in Figure 5.1.1 shows that each group member is connected to two other members, one on each side. This can make coordination easy when only one or two people need to be brought in for a decision. In this case, Erik and Callie are very reachable by Winston (because they are on either side of Winston in the circle), who could easily coordinate with them. However, if Winston needed to coordinate with Bill (on the other side of Callie) or Stephanie (on the other side of Erik), he would have to wait on Erik or Callie to reach that person, which could create delays. The circle can be a good structure for groups who are passing along a task and in which each member is expected to progressively build on the others’ work. A group of scholars co-authoring a research paper may work in such a manner, with each person adding to the paper and then passing it on to the next person in the circle. In this case, they can ask the previous person questions and write with the next person’s area of expertise in mind. The “Wheel” group structure in Figure 5.1.1 shows an alternative organization pattern. In this structure, Tara is very reachable by all members of the group because she is in the center of the wheel. This can be a useful structure when Tara is the person with the most expertise in the task or the leader who needs to review and approve work at each step before it is passed along to other group members. But Phillip and Shadow (found on opposite sides of Tara), for example, wouldn’t likely work together without Tara being involved.

Looking at the group structures, we can make some assumptions about the communication that takes place in them. The wheel is an example of a centralized structure, while the circle is decentralized. Research has shown that centralized groups are better than decentralized groups in terms of speed and efficiency (Ellis & Fisher, 1994). However, decentralized groups are more effective at solving complex problems. In centralized groups like the wheel, the person with the most connections, like Tara, is also more likely to be the leader of the group or at least have more status among group members, largely because that person has a broad perspective of what’s going on in the group. The most central person can also act as a gatekeeper. Since this person has access to the most information, which is usually a sign of leadership or status, he or she could consciously decide to limit the flow of information. However, in complex tasks, that person could become overwhelmed by the burden of processing and sharing information with all the other group members. The circle structure is more likely to emerge in groups where collaboration is the goal and a specific task and course of action aren’t required under time constraints. While the person who initiated the group or has the most expertise regarding the task may emerge as a leader in a decentralized group, equal access to information lessens such a rigid structure and the potential for a gatekeeping presence in the more centralized groups.

Interdependence

Small groups exhibit interdependence, meaning they share a common purpose and a common fate. If the actions of one or two group members lead to a group deviating from or not achieving its purpose, then all members of the group are affected. Conversely, if the actions of only a few of the group members lead to success, then all members of the group benefit. This is a major contributor to many college students’ dislike of group assignments because they feel a loss of control and independence that they have when they complete an assignment alone. This concern is valid in that their grades might suffer because of the negative actions of someone else or their hard work may go to benefit the group member who just skated by. Group meeting attendance is a clear example of the interdependent nature of group interaction. Many of us have arrived at a group meeting only to find half of the members present. In some cases, the group members who show up have to leave and reschedule because they can’t accomplish their tasks without the other members present. Group members who attend meetings but withdraw or don’t participate can also derail group progress. Although it can be frustrating to have your job, grade, or reputation partially dependent on the actions of others, the interdependent nature of groups can also lead to higher-quality performance and output, especially when group members are accountable for their actions.

Shared Identity

The shared identity of a group manifests in several ways. Groups may have official charters or mission and vision statements that lay out the identity of a group. The mission of this large organization influences the identities of the thousands of small groups called troops. Group identity is often formed around a shared goal and/or previous accomplishments, which adds dynamism to the group as it looks toward the future and back on the past to inform its present. Shared identity can also be exhibited through group names, slogans, songs, handshakes, clothing, or other symbols. At a family reunion, for example, matching t-shirts specially made for the occasion, dishes made from recipes passed down from generation to generation, and shared stories of family members who have passed away help establish a shared identity and social reality.

A key element of the formation of shared identity within a group is the establishment of the in-group as opposed to the out-group. The degree to which members share in the in-group identity varies from person to person and group to group. Even within a family, some members may not attend a reunion or get as excited about the matching t-shirts as others. Shared identity also emerges as groups become cohesive, meaning they identify with and like the group’s task and other group members. The presence of cohesion and a shared identity leads to a building of trust, which can also positively influence productivity and members’ satisfaction.

Types of Small Groups

There are many types of small groups, but the most common distinction made between types of small groups is that of task-oriented and relational-oriented groups (Hargie, 2011). Task-oriented groups are formed to solve a problem, promote a cause, or generate ideas or information (McKay, Davis, & Fanning, 1995). In such groups, like a committee or study group, interactions and decisions are primarily evaluated based on the quality of the final product or output. The three main types of tasks are production, discussion, and problem-solving tasks (Ellis & Fisher, 1994). Groups faced with production tasks are asked to produce something tangible from their group interactions such as a report, design for a playground, musical performance, or fundraiser event. Groups faced with discussion tasks are asked to talk through something without trying to come up with a right or wrong answer. Examples of this type of group include a support group for people with HIV/AIDS, a book club, or a group for new fathers. Groups faced with problem-solving tasks have to devise a course of action to meet a specific need. These groups also usually include a production and discussion component, but the end goal isn’t necessarily a tangible product or a shared social reality through discussion. Instead, the end goal is a well-thought-out idea. Task-oriented groups require honed problem-solving skills to accomplish goals, and the structure of these groups is more rigid than that of relational-oriented groups.

Relational-oriented groups are formed to promote interpersonal connections and are more focused on quality interactions that contribute to the well-being of group members. Decision-making is directed at strengthening or repairing relationships rather than completing discrete tasks or debating specific ideas or courses of action. All groups include task and relational elements, so it’s best to think of these orientations as two ends of a continuum rather than as mutually exclusive. For example, although a family unit works together daily to accomplish tasks like getting the kids ready for school and friendship groups may plan a surprise party for one of the members, their primary and most meaningful interactions are still relational.

These task-oriented group members are especially loyal and dedicated to the task and their other group members (Larson & LaFasto, 1989). In professional and civic contexts, the word team has become popularized as a means of drawing on the positive connotations of the term—connotations such as “high-spirited,” “cooperative,” and “hardworking.” Scholars who have spent years studying highly effective teams have identified several common factors related to their success. According to Adler & Elmhorst (2005), successful teams have

- clear and inspiring shared goals,

- a results-driven structure,

- competent team members,

- a collaborative climate,

- high standards for performance,

- external support and recognition, and

- ethical and accountable leadership.

Virtual Groups

Increasingly, small groups and teams are engaging in more virtual interaction. Virtual groups take advantage of new technologies and meet exclusively or primarily online to achieve their purpose or goal. Some virtual groups may complete their task without ever being physically face-to-face. Virtual groups bring with them distinct advantages and disadvantages.

Virtual groups are now common in academic, professional, and personal contexts, as classes meet entirely online, work teams interface using webinars or video-conferencing programs, and people connect around shared interests in a variety of online settings. Virtual groups are popular in professional contexts because they can bring together people who are geographically dispersed (Ahuja & Galvin, 2003). Virtual groups also increase the possibility for the inclusion of diverse members. The ability to transcend distance means that people with diverse backgrounds and diverse perspectives are more easily accessed than in many offline groups.

One disadvantage of virtual groups stems from the difficulties that technological mediation presents for the relational and social dimensions of group interactions (Walther & Bunz, 2005). As we will learn later, an important part of coming together as a group is the socialization of group members into the desired norms of the group. Since norms are implicit, much of this information is learned through observation or conveyed informally from one group member to another. In fact, in traditional groups, group members passively acquire 50 percent or more of their knowledge about group norms and procedures, meaning they observe rather than directly ask (Comer, 1991). Virtual groups experience more difficulty with this part of socialization than co-present traditional groups do since any form of electronic mediation takes away some of the richness present in face-to-face interaction.

To help overcome these challenges, members of virtual groups should be prepared to put more time and effort into building the relational dimensions of their group. Members of virtual groups need to make the social cues that guide new members’ socialization more explicit than they would in an offline group (Ahuja & Galvin, 2003). Group members should also contribute often, even if just supporting someone else’s contribution because increased participation has been shown to increase liking among members of virtual groups (Walther & Bunz, 2005). Virtual group members should also make an effort to put relational content that might otherwise be conveyed through nonverbal or contextual means into the verbal part of a message, as members who include little social content in their messages or only communicate about the group’s task are more negatively evaluated. Virtual groups who do not overcome these challenges will likely struggle to meet deadlines, interact less frequently, and experience more absenteeism. What follows are some guidelines to help optimize virtual groups (Walter & Bunz, 2005):

- Get started interacting as a group as early as possible, since it takes longer to build social cohesion.

- Interact frequently to stay on task and avoid having work build up.

- Start working toward completing the task while initial communication about setup, organization, and procedures is taking place.

- Respond overtly to other people’s messages and contributions.

- Be explicit about your reactions and thoughts since typical nonverbal expressions may not be received as easily in virtual groups as they would be in co-located groups.

- Set deadlines and stick to them.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Small Groups

Synergy refers to the potential for gains in performance or heightened quality of interactions when complementary members or member characteristics are added to existing ones (Larson Jr., 2010). Because of synergy, the final group product can be better than what any individual could have produced alone. When I worked in housing and residence life, I helped coordinate a “World Cup Soccer Tournament” for the international students who lived in my residence hall. As a group, we created teams representing different countries around the world, made brackets for people to track progress and predict winners, got sponsors, gathered prizes, and ended up with a very successful event that would not have been possible without the synergy created by our collective group membership. The members of this group were also exposed to international diversity which enriched our experiences, which is also an advantage of group communication.

Participating in groups can also increase our exposure to diversity and broaden our perspectives. Although groups vary in the diversity of their members, we can strategically choose groups that expand our diversity, or we can unintentionally end up in a diverse group. When we participate in small groups, we expand our social networks, which increases the possibility of interacting with people who have different cultural identities than ourselves. Since group members work together toward a common goal, shared identification with the task or group can give people with diverse backgrounds a sense of commonality that they might not have otherwise. Even when group members share cultural identities, the diversity of experience and opinion within a group can lead to broadened perspectives as alternative ideas are presented and opinions are challenged and defended. One of my favorite parts of facilitating the class discussion is when students with different identities and/or perspectives teach one another things in ways that I could not do on my own. This example brings together the potential of synergy and diversity. People who are more introverted or just avoid group communication and voluntarily distance themselves from groups—or are rejected from groups—risk losing opportunities to learn more about others and themselves.

There are also disadvantages to small group interaction. In some cases, one person can be just as or more effective than a group of people. Think about a situation in which a highly specialized skill or knowledge is needed to get something done. In this situation, one very knowledgeable person is probably a better fit for the task than a group of less knowledgeable people. Group interaction also tends to slow down the decision-making process. Individuals connected through a hierarchy or chain of command often work better in situations where decisions must be made under time constraints. When group interaction does occur under time constraints, having one “point person” or leader who coordinates action and gives final approval or disapproval on ideas or suggestions for actions is best.

Group communication also presents interpersonal challenges. A common problem is coordinating and planning group meetings due to busy and conflicting schedules. Some people also have difficulty with the other-centeredness and self-sacrifice that some groups require. The interdependence of group members that we discussed earlier can also create some disadvantages. Group members may take advantage of the anonymity of a group and engage in social loafing, meaning they contribute less to the group than other members or than they would if working alone (Karau & Williams, 1993). Social loafers expect that no one will notice their behaviors or that others will pick up their slack. It is this potential for social loafing that makes many students and professionals dread group work, especially those who tend to cover for other group members to prevent the social loafer from diminishing the group’s productivity or output.

Key Terms & Concepts

- dyad

- dyadic communication

- group identity

- in-group

- interdependency

- norms

- out-group

- relational-oriented groups

- social loafers

- socialization

- synergy

- task-oriented groups

- virtual groups

References

Licensing and Attribution: Content in this section is an adaptation of 13.1: Understanding Small Groups in Communication in the Real World – An Introduction to Communication Studies by Anonymous. It is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA license.