6.3: Romantic Relationships

Learning Objectives

- Define romantic relationships.

- Explain cultural differences that may determine the selection of a romantic partner.

- List and explain three influences that may determine whom we select as romantic partners.

- Explain the common stages in romantic relationships

- Identify the three relational dialectics present in interpersonal relationships.

Romantic Relationships

Like other relationships in our lives, romantic relationships play an important role in fulfilling our needs for intimacy and social connection. In many Western cultures, romantic relationships are voluntary. We are free to decide whom to date and form life-long romantic relationships. In some Eastern cultures, these decisions may be made by parents, or elders in the community, based on what is good for the family or social group. Even in Western societies, not everyone holds the same amount of freedom and power to determine their relational partners. Parents or society may discourage interracial, interfaith, or interclass relationships. While it is now legal for same-sex couples to marry, many same-sex couples still suffer political and social restrictions when making choices about marrying and having children. Much of the research on how romantic relationships develop is based on relationships in the West. In this context, romantic relationships can be viewed as voluntary relationships between individuals who intend to be a significant part of one another’s ongoing lives.

Think about your own romantic relationships for a moment. To whom are you attracted? Chances are they are people with whom you share common interests and encounter in your everyday routines such as going to school, work, or participation in hobbies or sports. In other words, self-identity, similarity, and proximity are three powerful influences when it comes to whom we select as romantic partners. We often select others that we deem appropriate for us as they fit our self-identity; heterosexuals pair up with other heterosexuals, lesbian women with other lesbian women, and so forth. Social class, religious preference, and ethnic or racial identity also influence as people are more likely to pair up with others of similar backgrounds. We are certainly not suggesting that we only have romantic relationships with carbon copies of ourselves. Over the last few decades, there have been some dramatic shifts when it comes to numbers and perceptions of interracial marriage. It is more and more common to see a wide variety of people that make up married couples. Logically speaking, it is difficult (although not impossible with the prevalence of social media and online dating services) to meet people outside of our immediate geographic area. In other words, if we do not have the opportunity to meet and interact with someone at least a little, how do we know if they are a person with whom we would like to explore a relationship? We cannot meet or maintain a long-term relationship, without sharing some sense of proximity.

Stages of Romantic Relationships

Just as there are stages in friendship, romantic relationships go through stages as well.

- In the initial stage of a romantic relationship, no interaction occurs when two people have not interacted.

- We move into invitational communication when we begin to send signals that we are interested in more interaction.

- Third, we engage in explorational communication where we increase our self-disclosure and time together to see if we are truly compatible.

- Fourth is a period of intensifying communication (“relationship high” where we cannot bear to be away from one another. At this stage, we tend to idealize one another or downplay faults.

- Fifth is revising communication when the relationship high wears off and we begin to see one another more realistically. It is at this point that couples must again make decisions about where to go with the relationship. Do they stay together and work toward long-term goals, or do they break up?

- Commitment is the sixth stage in the development of romantic relationships. This occurs when a couple makes the decision to make the relationship a permanent part of their lives. While marriage is an obvious sign of commitment, it is not the only signifier. Not all couples planning a future together legally marry.

Obviously, simply committing is not enough to maintain a relationship through tough times that occur as couples grow and change. Like a ship set on a destination, a couple must learn to steer through rough waves as well as calm waters. A couple can accomplish this by learning to communicate through the good and the bad. Navigating is when a couple continues to revise their communication and ways of interacting to reflect the changing needs of each person. Done well, life’s changes are more easily enjoyed when viewed as a natural part of the life cycle. The original patterns for managing dialectical tensions when a couple began dating, may not work when they are managing two careers, children, and a mortgage payment. Outside pressures such as children, professional duties, and financial responsibilities put added pressure on relationships that require attention and negotiation. If a couple neglects to practice effective communication with one another, coping with change becomes increasingly stressful and puts the relationship in jeopardy.

Not only do romantic couples progress through a series of stages of growth, but they also experience stages of deterioration. Deterioration does not necessarily mean that a couple’s relationship will end. Instead, couples may move back and forth from deterioration stages to growth stages throughout the course of their relationship.

Relational Dialectics

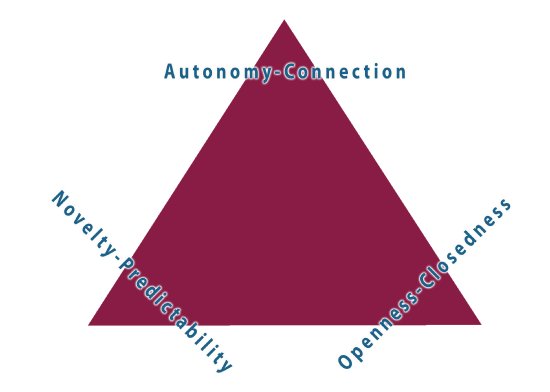

Relationship dialectics is a communication theory that states that people in relationships have contradictory desires or needs. These contradictory desires or impulses can create tension within the relationships if they are not managed properly. Baxter (1990) identifies three common relational dialectics or tensions as Autonomy-Connection, Novelty-Predictability, and Openness-Closedness.

Autonomy-Connection

Autonomy-Connection refers to our need to have a close connection with others as well as our need to have our own space and identity. We may miss our romantic partner when he or she is away but simultaneously enjoy and cherish that alone time. When you first enter a romantic relationship, you probably want to be around the other person as much as possible. As the relationship grows, you likely begin to desire fulfilling your need for autonomy, or alone time. In every relationship, each person must balance how much time to spend with the other, versus how much time to spend alone.

Novelty-Predictability

Novelty-Predictability is the idea that we desire predictability as well as spontaneity in our relationships. In every relationship, we take comfort in a certain level of routine as a way of knowing what we can count on the other person in the relationship. Such predictability provides a sense of comfort and security. However, it requires balance with novelty to avoid boredom. An example of balance might be friends who get together every Saturday for brunch but make a commitment to always try new restaurants each week.

Openness-Closedness

Openness-Closedness refers to the desire to be open and honest with others while at the same time not wanting to reveal everything about yourself to someone else. One’s desire for privacy does not mean they are shutting out others. It is a normal human need. We tend to disclose the most personal information to those with whom we have the closest relationships.

In general, there is no one right way to understand and manage dialectical tensions since every relationship is unique. However, to always satisfy one need and ignore the other may be a sign of trouble in the relationship (Baxter). It is important to remember that relational dialectics are a natural part of our relationships and that we have a lot of choice, freedom, and creativity in how we work them out with our relational partners. It is also important to remember that dialectical tensions are negotiated differently in each relationship. The ways we self-disclose and manage dialectical tensions contribute greatly to the overall communication climate of the relationship.

Key Terms & Concepts

- autonomy-connection

- commitment

- explorational communication

- intensifying communication

- invitational communication

- no interaction

- novelty-predictability

- openness-closedness

- proximity

- revising communication

- self-identity

- similarity

References

Baxter, L. A. (1990). Dialectical contradictions in relational development. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 7, 69-88.

Licensing and Attribution: Content in this section is an adaptation of 6.4: Romantic Relationships in Competent Communication (2nd edition) by Lisa Coleman, Thomas King, & William Turner. It is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA license.