6.6: Conflict Management

Learning Objectives

- Define interpersonal conflict.

- Compare and contrast the five styles of interpersonal conflict management.

- List strategies for effectively managing conflict through collaboration.

To whom do you have the most conflict right now? If you still live at home with a parent or parents, you may have daily conflicts with your family as you try to balance your autonomy, or desire for independence, with the practicalities of living under your family’s roof. If you’ve recently moved into an apartment or house, you may be negotiating roommate conflicts as you adjust to living with someone you may not know very well. You probably also have experiences with conflict in romantic relationships, in the workplace, and maybe even at school. So think back and ask yourself, “How well do I handle conflict?” As with all areas of communication, we can improve if we have the background knowledge and the motivation to reflect on and enhance our communication skills.

Examining Interpersonal Conflict

Interpersonal conflict occurs in interactions where there are real or perceived incompatible goals or opposing viewpoints. Interpersonal conflict may be expressed verbally or nonverbally, ranging from mild nonverbal silent treatment to a very loud shouting match. Interpersonal conflict is, however, distinct from interpersonal violence, which escalates beyond communication to include abuse. Domestic violence is a serious issue that goes beyond the conflict we will discuss.

While conflict may be uncomfortable and challenging, it doesn’t have to be negative. In fact, it is inevitable. Since conflict is present in our personal and professional lives, the ability to manage conflict and negotiate desirable outcomes can help us be more successful at both. Whether you and your partner are trying to decide what brand of flat-screen television to buy or discussing the upcoming political election with your mother, the potential for conflict is present. In professional settings, the ability to engage in conflict management, sometimes called conflict resolution, is a necessary and valued skill.

Using strategies for managing conflict situations can make life more pleasant than letting a situation stagnate or escalate. The negative effects of poorly handled conflict could range from an awkward last few weeks of the semester with a college roommate to being fired from your job. There is no absolute right or wrong way to handle a conflict. Remember that being a competent communicator doesn’t mean that you follow a set of absolute rules. Rather, a competent communicator assesses multiple contexts and applies or adapts communication tools and skills to fit the situation.

Strategies for Managing Conflict

When we ask others what they want to do when they experience conflict, most of the time they say “resolve it.” While this is understandable, also important to understand is that conflict is ongoing in all relationships, and our approach to conflict sometimes should be to “manage it” instead of always trying to “resolve it.”

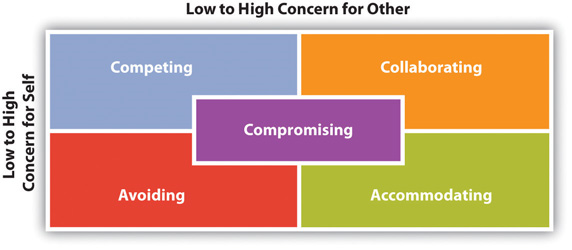

One way to understand options for managing conflict is by knowing five major strategies people may use for managing conflict. As you read about each of these below, you will see that some are likely to be more successful than others. You can also refer to Figure 6.6.1 to see where each fits in.

Long description of Figure 6.6.1: A 2×2 matrix with Concern for Self on the y-axis and Concern for Others on the x-axis. High concern for self and low concern for others is Competing. High concern for self and high concern for others is Collaborating. Low concern for self and low concern for others is Avoiding. Low concern for self and high concern for others is Accommodating. Displayed in the middle of this matrix and overlapping all four boxes is Comprising. Each of these is discussed further below.

Competing

When people select the competing or the win-lose approach, they exhibit high concern for the self and low concern for the other person. The goal here is to win the conflict. This approach is often characterized by loud, forceful, and interrupting communication. Again, this is analogous to sports. Too often, we avoid conflict because we believe the only other alternative is to try to dominate the other person. In relationships where we care about others or in conflicts at work, it’s no wonder this strategy can seem unappealing. Competing sometimes leads to aggression, although not always. Aggressive communication may involve insults, profanity, and yelling, or threats of punishment if you do not get your way.

Avoiding

When people avoid a conflict they may suppress feelings of frustration or walk away from a situation. This style of conflict management often indicates a low concern for self and a low concern for the other, and no direct communication about the conflict takes place. This is not always the case, however. In fact, there may be times when this is the best strategy. Take, for example, a heated argument between D’Shaun and Pat. Pat is about to make a hurtful remark out of frustration. Instead, she decides that she needs to avoid this argument right now until she and D’Shaun can come back and discuss things in a calmer fashion. Or we may decide to avoid conflict for other reasons. If you view the conflict as having little importance to you, it may be better to ignore it. If the person you’re having conflict with will only be working in your office for a week, you may perceive a conflict to be temporary and choose to avoid it. In general, avoiding doesn’t work. For one thing, you can not communicate. Even when we try to avoid conflict, we may intentionally or unintentionally give our feelings away through our verbal and nonverbal communication, such as rolling our eyes or sighing. Consistent conflict avoidance over the long term generally has negative consequences for a relationship because neither person is willing to participate in the conflict management process.

Accommodating

The accommodating conflict management style indicates a moderate degree of concern for self and others. Sometimes, this style is viewed as passive or submissive, in that someone complies with or obliges another without providing personal input. However, it could be that the person involved in the conflict values the relationship more than the issue. The context for and motivation behind accommodating play an important role in whether or not it is an appropriate strategy. For example, if there is little chance that your own goals can be attained, or if the relationship might be damaged if you insist on your own way, accommodating could be appropriate. On the other hand, if you constantly accommodate with little reciprocation by your partner, this style can be personally damaging.

Compromising

The compromising style is evident when both parties are willing to give up something in order to gain something else. It shows a moderate concern for self and the other. When environmental activist, Julia Butterfly Hill agreed to end her two-year-long tree-sit in Luna as a protest against the logging practices of Pacific Lumber Company (PALCO), and pay them $50,000 in exchange for their promise to protect Luna and not cut within a 20-foot buffer zone, she and PALCO reached a compromise. If one of the parties feels the compromise is unequal they may be less likely to stick to it long term. When conflict is unavoidable, many times people will opt for a compromise. One of the problems with compromise is that neither party fully gets their needs met. If you want Mexican food and your friend wants pizza, you might agree to compromise and go someplace that serves Mexican pizza. While this may seem like a good idea, you may have really been craving a burrito and your friend may have really been craving a pepperoni pizza. In this case, while the compromise brought together two food genres, neither person got their desire met. Compromising may be a good strategy when there are time limitations or when prolonging a conflict may lead to relationship deterioration. Compromise may also be good when both parties have equal power or when other resolution strategies have not worked (Macintosh & Stevens, 2008).

Collaborating

Finally, collaborating demonstrates a high level of concern for both self and others. Using this strategy, individuals agree to share information, feelings, and creativity to try to reach a mutually acceptable solution that meets both of their needs. In our food example above, one strategy would be for both people to get the food they want, then take it on a picnic in the park. This way, both people are getting their needs met fully, and in a way that extends beyond original notions of win-lose approaches for managing the conflict. The downside to this strategy is that it is very time-consuming and requires high levels of trust.

Tips for Managing Interpersonal Conflict

- Do not view the conflict as a contest you are trying to win.

- Distinguish the person or people from the problem. (Don’t make it personal and don’t engage in blaming and name-calling.)

- Determine what underlying needs may be driving the other person’s demands (sometimes needs can still be met in a different way).

- Identify areas of common ground or shared interests that you can work from to develop solutions.

- Ask questions to allow them to clarify and to help you understand their perspective.

- Listen carefully and provide verbal and nonverbal feedback.

- Remain flexible and realize there may be solutions yet to be discovered.

Key Terms & Concepts

- accommodating

- avoiding

- collaborating

- competing

- compromising

- conflict management

- interpersonal conflict

References

Macintosh, G., & Stevens, C. (2008). Personality, motives, and conflict strategies in everyday service encounters. International Journal of Conflict Management, 19(2), 115.

Rahim, M. A. (1983). A measure of styles of handling interpersonal conflict. Academy of Management Journal, 26(2), 368-76.

Licensing and Attribution: Content in this section is a combination of:

6.7: Conflict Management in Communication in the Real World by University of Minnesota. It is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA license, except where otherwise noted.

7.3: Approaching Interpersonal Conflict in Exploring Relationship Dynamics by Maricopa Community Colleges. It is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA license.