6.4: Communication and Family

Learning Objectives

- Explain the characteristics of a family

- Describe and explain how our early concept of family influences us in the future.

- Examine whether and how our view of the family still shapes our expectations and behaviors.

What is a Family?

The third primary type of interpersonal relationship we engage in is that of family. Unlike friendships and romantic relationships, which are usually voluntary, we have no choice in our birth family. What is family? Is family created by legal ties or the bond of sharing common blood? Or, can a family be considered people who share a commitment to one another? In an effort to recognize the diversity of families, we define family as two or more people related by marriage, blood, adoption, or choice, who live together for an extended period of time. Families are characterized by relationships among family members. Family relations are typically long-term.

Characteristics of a Family

Pearson (1992) suggests that in families, members tend to play predictable roles, form a relational transactional group, share a living space for prolonged periods of time, and create interpersonal images of family that evolve over time. Let’s take a few moments to unpack these characteristics.

Each Family Member Plays a Predictable Role

Most family members take on predictable individual roles (parent, child, older sibling) in our family relationships. Similarly, family members tend to take on predictable communication patterns within the family. For example, your younger brother may act as the family peacemaker, while your older sister always initiates fights with her siblings.

Families Are Characterized by Relationships Among Members

Not only is a family made up of individual members, but it is also largely defined by the relationships among the members. A family that consists of two opposite-sex parents, an older sister, her husband and three kids, a younger brother, his new wife, and two kids from a first marriage is largely defined by the relationships among the family members. All of these people have a role in the family and interact with others in fairly consistent ways according to their roles.

Families Usually Occupy a Common Living Space Over an Extended Period of Time

One consistent theme when defining family is recognizing that family members typically live under the same roof for an extended period of time. We certainly include extended family within our definition, but for the most part, our notions of the family include those people with whom we share or have shared, common space over a period of time.

We Learn Cultural and Personal Values From Our Family

From our families, we learn important cultural and personal values concerning intimacy, spirituality, communication, and respect. Parents and other family members model behaviors that shape how we interact with others. From our family, we form an image of what “family” means and may try to keep that image or ideal throughout our lifetime. As an adult, you may define family as your immediate family, consisting of your parents and a sibling. However, your romantic partner may see family as consisting of parents, siblings, aunts, uncles, cousins, and grandparents. Each of you performs different communication behaviors to maintain your image of family. This can even filter down to the way you view holidays and expectations for family get-togethers.

Family Communication Processes

Think about how much time we spend communicating with family members over the course of our lives. As children, most of us spend much of our time talking to parents, grandparents, and siblings. As we become adolescents, our peer groups become more central, and we may even begin to resist communicating with our family during the rebellious teenage years. However, as we begin to choose and form our own families, we once again spend much time engaging in family communication. Additionally, family communication is our primary source of intergenerational communication or communication between people of different age groups.

Family Interaction Rituals

You may have heard or used the term “family time” in your own family. What does family time mean? Relational cultures are built on interaction routines and rituals. Families also have interaction norms that create, maintain, and change communication climates. The notion of family time hasn’t been around for too long but was widely communicated and represented in the popular culture of the 1950s (Daly, 2001). When we think of family time, or quality time as it’s sometimes called, we usually think of a romanticized ideal of family time spent together.

While family rituals and routines can be fun and entertaining bonding experiences, they can also bring about interpersonal conflict and strife. Just think about Clark W. Griswold’s string of well-intentioned but misguided attempts to manufacture family fun in the National Lampoon’s Vacation series.

Families engage in a variety of rituals that demonstrate symbolic importance and shared beliefs, attitudes, and values. Three main types of relationship rituals are patterned family interactions, family traditions, and family celebrations (Wolin & Bennett, 1984). Patterned family interactions are the most frequent rituals and do not have the degree of formality of traditions or celebrations. Patterned interactions may include mealtime, bedtime, receiving guests at the house, or leisure activities. Mealtime rituals may include a rotation of who cooks and who cleans, and many families have set seating arrangements at their dinner table.

Family traditions are more formal, occur less frequently than patterned interactions, vary widely from family to family, and include birthdays, family reunions, and family vacations. Birthday traditions may involve a trip to a favorite restaurant, baking a cake, or hanging streamers. Family reunions may involve making t-shirts for the group or counting up the collective age of everyone present. Family road trips may involve predictable conflict between siblings, or playing car games like “I Spy” or trying to find the most number of license plates from different states.

Last, family celebrations are also formal, have more standardization between families, may be culturally specific, help transmit values and memories through generations, and include rites of passage and religious and secular holiday celebrations. Thanksgiving, for example, is formalized as a national holiday and is celebrated in similar ways by many families in the United States. Rites of passage mark life-cycle transitions such as graduations, weddings, quinceañeras, or bar mitzvahs. While graduations are secular and may vary in terms of how they are celebrated, quinceañeras have cultural roots in Latin America, and bar mitzvahs are a long-established religious rite of passage in the Jewish faith.

Conversation and Conformity Orientations

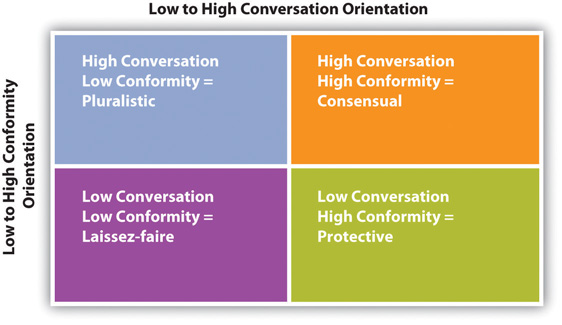

The amount, breadth, and depth of conversation between family members vary from family to family. Additionally, some families encourage self-exploration and freedom, while others expect family unity and control. This variation can be better understood by examining two key factors that influence family communication: conversation orientation and conformity orientation (Koerner & Fitzpatrick, 2002). A given family can be higher or lower on either dimension and how a family rates on each of these dimensions can be used to determine a family type. Figure 6.4.1 shows a matrix of various types of families based on conformity and conversation.

Long description of Figure 6.4.1: A 2×2 matrix with conformity orientation on the y-axis and conversation orientation on the x-axis. A family with high conversation and low conformity is pluralistic. A family with high conversation and high conformity is consensual. A family with low conversation and low conformity is laissez–faire. A family with low conversation and high conformity is protective.

To determine conversation orientation, we determine to what degree a family encourages members to interact and communicate (converse) about various topics. Members within a family with a high conversation orientation communicate with each other freely and frequently about activities, thoughts, and feelings. This unrestricted communication style leads to all members, including children, participating in family decisions. Parents in high conversation orientation families believe that communicating with their children openly and frequently leads to a more rewarding family life and helps to educate and socialize children, preparing them for interactions outside the family. Members of a family with a low conversation orientation do not interact with each other as often, and topics of conversation are more restricted, as some thoughts are considered private. For example, not everyone’s input may be sought for decisions that affect everyone in the family, and open and frequent communication is not deemed important for family functioning or for a child’s socialization.

Conformity orientation is determined by the degree to which a family communication climate encourages conformity and agreement regarding beliefs, attitudes, values, and behaviors (Koerner & Fitzpatrick, 2002). A family with a high conformity orientation fosters a climate of uniformity, and parents decide on guidelines for what to conform to. Children are expected to be obedient, and conflict is often avoided to protect family harmony. This more traditional family model stresses interdependence among family members, which means space, money, and time are shared among immediate family, and family relationships take precedence over those outside the family. A family with a low conformity orientation encourages diversity of beliefs, attitudes, values, and behaviors and assertion of individuality. Relationships outside the family are seen as important parts of growth and socialization, as they teach lessons about and build confidence for independence. Members of these families also value personal time and space.

Determining where your family falls on the conversation and conformity dimensions is more instructive when you know the family types that result, which are consensual, pluralistic, protective, and laissez-faire (Koerner & Fitzpatrick, 2002). A consensual family is high in both conversation and conformity orientations, and they encourage open communication but also want to maintain the hierarchy within the family that puts parents above children. This creates some tension between a desire for both openness and control. Parents may reconcile this tension by hearing their children’s opinions, making the ultimate decision themselves, and then explaining why they made the decision they did. A pluralistic family is high in conversation orientation and low in conformity. Open discussion is encouraged for all family members, and parents do not strive to control their children’s or each other’s behaviors or decisions. Instead, they value the life lessons that a family member can learn by spending time with non–family members or engaging in self-exploration. A protective family is low in conversation orientation and high in conformity, expects children to be obedient to parents, and does not value open communication. Parents make the ultimate decisions and may or may not feel the need to share their reasoning with their children. If a child questions a decision, a parent may simply respond with “Because I said so.” A laissez-faire family is low in conversation and conformity orientations, has infrequent and/or short interactions, and doesn’t discuss many topics. Remember that pluralistic families also have a low conformity orientation, which means they encourage children to make their own decisions to promote personal exploration and growth. Laissez-faire families are different in that parents don’t have an investment in their children’s decision-making, and in general, members of this type of family are “emotionally divorced” from each other (Koerner & Fitzpatrick, 2002).

Key Terms & Concepts

- conformity orientation

- consensual family

- conversation orientation

- family

- family celebrations

- family time

- family traditions

- high conformity orientation

- high conversation orientation

- intergenerational communication

- laissez-faire family

- low conformity orientation

- low conversation orientation

- patterned family interactions

- pluralistic family

- protective family

- quality time

References

Daly, K. J. (2001). Deconstructing family time: From ideology to lived experience. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 63(2), 283-295.

Koerner, A. F., & Fitzpatrick, M. A. (2002). Toward a theory of family communication. Communication Theory 12(1), 85-89.

Pearson, J. C. (1992). Communication in the family: Seeking satisfaction in changing times (vol. 2). Harper & Row.

Wolin, S. J., & Bennett, L. A. (1984). Family rituals. Family Processes, 23(3), 401-420.

Licensing and Attribution: Content in this section is a combination of:

6.5: Family in Competent Communication (2nd edition) by Lisa Coleman, Thomas King, & William Turner. It is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA license.

5.3: Communication and Families in Exploring Relationship Dynamics by Maricopa Community Colleges. It is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA license.