Part 3: Ethical Duties

41 What is “social contract theory”?

Our final ethical framework is social contract theory. This is based more heavily on political theory than our other frameworks, and begins by considering the role of government. People who do not see the need for public goods,[1] (including laws, court systems, and the government goods and services just cited) often question why there needs to be a government at all. One response might be, “Without government, there would be no corporations.” Thomas Hobbes believed that people in a “state of nature” would rationally choose to have some form of government. He called this the social contract. Hobbes and Locke are generally regarded as the preeminent social contract theorists. In your own lives and in this course, you will see an ongoing balancing act between human desires for freedom and human desires for order; it is an ancient tension. Some commentators also see a kind of social contract between corporations and society; in exchange for perpetual duration and limited liability, the corporation has some corresponding duties toward society. Also, if a corporation is legally a “person,” as the Supreme Court reaffirmed in 2010, then some would argue that if this corporate person commits three felonies, it should be locked up for life and its corporate charter revoked!

Modern social contract theorists, such as Thomas Donaldson and Thomas Dunfee (Ties that Bind, 1999), observe that various communities, not just nations, make rules for the common good. Your college or school is a community, and there are communities within the school (fraternities, sororities, etc) that have rules, norms, or standards that people can buy into or not. If not, they can exit from that community, just as we are free (though not without cost) to reject US citizenship and take up residence in another country.

Donaldson and Dunfee’s integrative social contracts theory stresses the importance of studying the rules of smaller communities along with the larger social contracts made in states (such as Colorado or California) and nation-states (such as the United States or Germany). Our Constitution can be seen as a fundamental social contract.

It is important to realize that a social contract can be changed by the participants in a community, just as the US Constitution can be amended. Social contract theory is thus dynamic—it allows for structural and organic changes. Ideally, the social contract struck by citizens and the government allows for certain fundamental rights such as those we enjoy in the United States, but it need not. People can give up freedom-oriented rights (such as the right of free speech or the right to be free of unreasonable searches and seizures) to secure order (freedom from fear, freedom from terrorism). Thus the rights that people have—in positive law—come from whatever social contract exists in the society. This view differs from that of the deontologists and that of the natural-law thinkers such as Gandhi, Jesus, or Martin Luther King Jr., who believed that rights come from God or, in less religious terms, from some transcendent moral order.

The relationship between rights and duties—in both law and ethics—calls for some explanations:

- If you have a right of free expression, the government has a duty to respect that right but can put reasonable limits on it. For example, you can legally say whatever you want about the US president, but you can’t get away with threatening the president’s life. Even if your criticisms are strong and insistent, you have the right (and our government has the duty to protect your right) to speak freely. In Singapore during the 1990s, even indirect criticisms—mere hints—of the political leadership were enough to land you in jail or at least silence you with a libel suit.

- Rights and duties exist not only between people and their governments but also between individuals. Your right to be free from physical assault is protected by the law in most states, and when someone walks up to you and punches you in the nose, your rights—as set forth in the positive law of your state—have been violated. Thus other people have a duty to respect your rights and to not punch you in the nose.

- Your right in legal terms is only as good as your society’s willingness to provide legal remedies through the courts and political institutions of society.

A distinction between basic rights and nonbasic rights may also be important. Basic rights may include such fundamental elements as food, water, shelter, and physical safety. Another distinction is between positive rights (the right to bear arms, the right to vote, the right of privacy) and negative rights (the right to be free from unreasonable searches and seizures, the right to be free of cruel or unusual punishments). Yet another is between economic or social rights (adequate food, work, and environment) and political or civic rights (the right to vote, the right to equal protection of the laws, the right to due process).

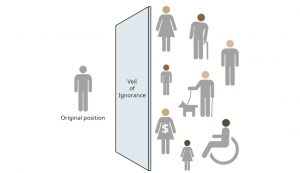

To apply social contract theory, it can be helpful to consider oneself behind a “veil of ignorance” in which one does not know which of the parties affected by a decision one will be in the future. For example, if one didn’t know whether one were a board member, employee, shareholder, or customer, what decision would be made? Thinking through a veil of ignorance forces us to consider whether we would like the outcome on any one of these groups.

This thought process has several implications: first, rules for cooperation should benefit more than just some, otherwise nobody behind a veil of ignorance would agree! Thus, slavery is immediately unethical, because nobody who might become enslaved would agree to the system ahead of time. Second, if another breaks the social contract, it may be justified in turn. For example, if someone attacks you, self-defense (attacking in return for defensive purposes) may be justified. Third, legal rules become important, because they maintain the social contract. Of course, an unjust law may violate a social contract itself!

For more, see this video from “Crash Course Philosophy”:

Exercises

- Consider the form of government in the United States. What are the essential elements of this large “social contract”?

- Goods that are useful to society (parks, education, national defense, highways) that would ordinarily not be produced by private enterprise. Public goods require public revenues (taxes) and political support to be adequately maintained. ↵

The idea that people in a civil society have voluntarily given up some of their freedoms to have ordered liberty with the assistance of a government that will support that liberty.