Part 4: Duties and Stakeholder Theory

47 What is “stakeholder theory”?

There are two main views about what the corporation’s duties are. The first view—maximizing profits—has classically been influential among managers. This view largely follows the idea of Milton Friedman that the duty of a manager is to maximize return on investment to the owners. In essence, managers’ legally prescribed duties are those that make their employment possible. In terms of the legal organization of the corporation, the shareholders elect directors who hire managers, who have legally prescribed duties toward both directors and shareholders. Those legally prescribed duties are a reflection of the fact that managers are managing other people’s money and have a moral duty to act as a responsible agent for the owners. In law, this is called the manager’s fiduciary duty. Directors have the same duties toward shareholders. Friedman emphasized the primacy of this duty in his writings about corporations and social responsibility.

Others have challenged the notion that corporate managers have no real duties except toward the owners (shareholders). After all, early corporations only existed if they had an express public interest! By changing two letters in shareholder, stakeholder theorists widened the range of people and institutions that a corporation should pay moral consideration to. Thus they contend that a corporation, through its management, has a set of responsibilities toward nonshareholder interests.

Advocates of this counterpoint might also point out two difficulties with the “maximize profit” alone approach to business strategy. First, very different decisions might be reached based on the timeframe involved in the maximization problem. Some decisions that maximize profit in the short term might be disastrous for profit in the long run. E.g., Enron. When considering long-term profit, many decisions such as investing in customer or community relations are rational, even if they have no short-term effect on profits. Second, the best way to maximize profit might be to adopt a more stakeholder-centric view of business! Nobody likes to visit a business that they feel does not appreciate them, and nobody likes to work for a company that does not value employees. In anything but the short term, considering the needs of crucial stakeholders beyond shareholders alone is almost always a sound business decision, resulting in long-term gains for shareholders as well!

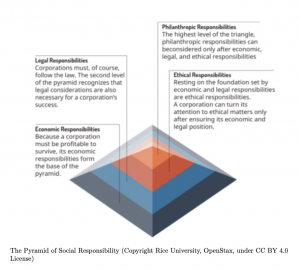

Many business theorists have found it useful to consider the responsibilities of business as a pyramid, with economic responsibilities forming the base (as business must make a profit to exist), legal responsibilities above that (as failure to follow the law can lead to severe consequences), followed by ethical responsibilities (which are expected by society, even if not legally required), and finally, at the top of the pyramid, philanthropic or discretionary responsibilities. This model emphasizes the variety of responsibilities faced by business entities. At the same time, this kind of pyramid thinking may cloud the fact that each type of responsibility a business faces is related. A company that breaks the law or an unethical company will likely face long-term problems with its economic responsibilities. A company can often use philanthropic projects which tie deeply to its economic responsibilities, such as a software company sponsoring training programs for high school students who may then become employees of the company later in life.

Stakeholders of a company include its employees, suppliers, customers, the local community, government, and the environment.[1] Stakeholder is a deliberate play on the word shareholder, to emphasize that companies have obligations that extend beyond the bottom-line aim of maximizing profits. A stakeholder is anyone who most would agree is significantly affected (positively or negatively) by the decision of the company, and who in turn has the potential to affect the company. (Note the bi-directional red arrows in the diagram below.)

There is one vital fact about corporations (and many other legal entities, such as LLCs): the corporation is a creation of the law. Without law (and government), corporations would not have existence. The key concept for corporations is the legal fact of limited liability. The benefit of limited liability for shareholders of a corporation meant that larger pools of capital could be aggregated for larger enterprises; shareholders could only lose their investments should the venture fail in any way, and there would be no personal liability and thus no potential loss of personal assets other than the value of the corporate stock. Before New Jersey and Delaware competed to make incorporation as easy as possible and beneficial to the incorporators and founders, those who wanted the benefits of incorporation had to go to legislatures—usually among the states—to show a public purpose that the company would serve.

In the late 1800s, New Jersey and Delaware changed their laws to make incorporating relatively easy. These two states allowed incorporation “for any legal purpose,” rather than requiring some public purpose. Thus it is government (and its laws) that makes limited liability happen through the corporate form. That is, only through the consent of the state and armed with the charter granted by the state can a corporation’s shareholders have limited liability. This is a right granted by the state, a right granted for good and practical reasons for encouraging capital and innovation. But with this right comes a related duty, not clearly stated at law, but assumed when a charter is granted by the state: that the corporate form of doing business is legal because the government feels that it is socially useful to do so.

Implicitly, then, there is a social contract between governments and corporations: as long as corporations are considered socially useful, they can exist. But do they have explicit social responsibilities? Milton Friedman’s position [considered without the caveats suggested in the prior Question] suggests that having gone along with legal duties, the corporation can ignore any other social obligations. But there are others (such as advocates of stakeholder theory) who would say that a corporation’s social responsibilities go beyond just staying within the law and go beyond the corporation’s shareholders to include a number of other important stakeholders, those whose lives can be affected by corporate decisions. According to stakeholder theorists, corporations (and other business organizations) must pay attention not only to the bottom line but also to their overall effect on stakeholders. Public perception of a company’s unfairness, uncaring, disrespect, destruction of the environment, or lack of trustworthiness often leads to long-term failure, whatever the short-term successes or profits may be. A socially responsible corporation is likely to consider the impact of its decisions on a wide range of stakeholders, not just shareholders. Focusing on long-term relationships with stakeholders can thus be key to long-term financial success of a company.

Exercises

- For the company you have been considering in these exercises, what are their major stakeholders?

- The environment is often considered a special stakeholder, because it does not maintain it’s own “voice” with which to interact with the company. However, due to the extraordinary importance of the physical environment in which a company operates, it is generally included among lists of stakeholders. ↵