Part 4: Duties and Stakeholder Theory

45 What is the law of “agency”, and why does it matter?

We begin analysis of stakeholders in perhaps an unusual place: a brief foray into the law of agency. This is because stakeholder theory contrasts strongly with popular economic views that build on the law of agency (covered here), and fiduciary duties (which we considered in Part 2). To understand stakeholder theory, we need to have a background in agency law. You will recognize many of these principles from our discussion of fiduciary duties, but with expanded discussion here. This discussion will also help set up our consideration of employees, as a special category of stakeholder, later in the text.

An agent is a person who acts in the name of and on behalf of another, having been given and assumed some degree of authority to do so. Most organized human activity—and virtually all commercial activity—is carried on through agency. No corporation would be possible, even in theory, without such a concept. We might say “General Motors is building cars in China,” for example, but we can’t shake hands with General Motors. “The General,” as people say, exists and works through agents. Likewise, partnerships and other business organizations rely extensively on agents to conduct their business. Indeed, it is not an exaggeration to say that agency is the cornerstone of enterprise organization. In a partnership each partner is a general agent, while under corporation law the officers and all employees are agents of the corporation.

The existence of agents does not, however, require a whole new law of torts or contracts. A tort is no less harmful when committed by an agent; a contract is no less binding when negotiated by an agent. What does need to be taken into account, though, is the manner in which an agent acts on behalf of his principal and toward a third party.

Consider John Alden (1599–1687), one of the most famous agents in American literature. He is said to have been the first person from the Mayflower to set foot on Plymouth Rock in 1620; he was a carpenter, a cooper (barrel maker), and a diplomat. His agency task—of interest here—was celebrated in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “The Courtship of Miles Standish.” He was to woo Priscilla Mullins (d. 1680), “the loveliest maiden of Plymouth,” on behalf of Captain Miles Standish, a valiant soldier who was too shy to propose marriage. Standish turned to John Alden, his young and eloquent protégé, and beseeched Alden to speak on his behalf, unaware that Alden himself was in love with Priscilla. Alden accepted his captain’s assignment, despite the knowledge that he would thus lose Priscilla for himself, and sought out the lady. But Alden was so tongue-tied that his vaunted eloquence fell short, turned Priscilla cold toward the object of Alden’s mission, and eventually led her to turn the tables in one of the most famous lines in American literature and poetry: “Why don’t you speak for yourself, John?” John eventually did: the two were married in 1623 in Plymouth.

Let’s analyze this sequence of events in legal terms—recognizing, of course, that this example is an analogy and that the law, even today, would not impose consequences on Alden for his failure to carry out Captain Standish’s wishes. Alden was the captain’s agent: he was specifically authorized to speak in his name in a manner agreed on, toward a specified end, and he accepted the assignment in consideration of the captain’s friendship. He had, however, a conflict of interest. He attempted to carry out the assignment, but he did not perform according to expectations. Eventually, he wound up with the prize himself. Here are some questions to consider, the same questions that will recur throughout the discussion of agency:

- How extensive was John’s authority? Could he have made promises to Priscilla on the captain’s behalf—for example, that Standish would have built her a fine house?

- Could he, if he committed a tort, have imposed liability on his principal? Suppose, for example, that he had ridden at breakneck speed to reach Priscilla’s side and while en route ran into and injured a pedestrian on the road. Could the pedestrian have sued Standish?

- Suppose Alden had injured himself on the journey. Would Standish be liable to Alden?

- Is Alden liable to Standish for stealing the heart of Priscilla—that is, for taking the “profits” of the enterprise for himself?

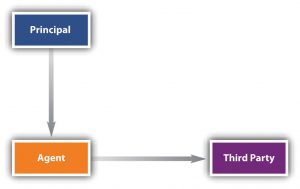

As these questions suggest, agency law often involves three parties—the principal, the agent, and a third party. It therefore deals with three different relationships: between principal and agent, between principal and third party, and between agent and third party. These relationships can be summed up in a simple diagram:

The agent owes the principal duties in two categories: the fiduciary duty and a set of general duties imposed by agency law. But these general duties are not unique to agency law; they are duties owed by any employee to the employer.

In a nonagency contractual situation, the parties’ responsibilities terminate at the border of the contract. There is no relationship beyond the agreement. This literalist approach is justified by the more general principle that we each should be free to act unless we commit ourselves to a particular course.

Duties of an Agent

But the agency relationship is more than a contractual one, and the agent’s responsibilities go beyond the border of the contract. Agency imposes a higher duty than simply to abide by the contract terms. It imposes a fiduciary duty. The law infiltrates the contract creating the agency relationship and reverses the general principle that the parties are free to act in the absence of agreement. As a fiduciary of the principal, the agent stands in a position of special trust. Their responsibility is to subordinate their self-interest to that of the principal. The fiduciary responsibility is imposed by law. The absence of any clause in the contract detailing the agent’s fiduciary duty does not relieve them of it. The duty contains several aspects.

Duty to Avoid Self-Dealing

A fiduciary may not lawfully profit from a conflict between his personal interest in a transaction and his principal’s interest in that same transaction. A broker hired as a purchasing agent, for instance, may not sell to his principal through a company in which he or his family has a financial interest. The penalty for breach of fiduciary duty is loss of compensation and profit and possible damages for breach of trust.

Duty to Preserve Confidential Information

To further his objectives, a principal will usually need to reveal a number of secrets to his agent—how much he is willing to sell or pay for property, marketing strategies, and the like. Such information could easily be turned to the disadvantage of the principal if the agent were to compete with the principal or were to sell the information to those who do. The law therefore prohibits an agent from using for their own purposes or in ways that would injure the interests of the principal, information confidentially given or acquired. This prohibition extends to information gleaned from the principal though unrelated to the agent’s assignment: “[A]n agent who is told by the principal of his plans, or who secretly examines books or memoranda of the employer, is not privileged to use such information at his principal’s expense.”[1] Nor may the agent use confidential information after resigning their agency. Though they are free, in the absence of contract, to compete with the former principal, they may not use information learned in the course of the agency, such as trade secrets and customer lists.

Other Duties

In addition to fiduciary responsibility (and whatever special duties may be contained in the specific contract) the law of agency imposes other duties on an agent. These duties are not necessarily unique to agents: a nonfiduciary employee could also be bound to these duties on the right facts.

Duty of Skill and Care

An agent is usually taken on because they have special knowledge or skills that the principal wishes to tap. The agent is under a legal duty to perform the work with the care and skill that is “standard in the locality for the kind of work which he is employed to perform” and to exercise any special skills, if these are greater or more refined than those prevalent among those normally employed in the community. In short, the agent may not lawfully do a sloppy job.

Duty of Good Conduct

In the absence of an agreement, a principal may not ordinarily dictate how an agent must live their private life. An overly fastidious florist may not instruct their truck driver to steer clear of the local bar on the way home from delivering flowers at the end of the day. But there are some jobs on which the personal habits of the agent may have an effect. The agent is not at liberty to act with impropriety or notoriety, so as to bring disrepute on the business in which the principal is engaged. A lecturer at an anti-alcohol clinic may be directed to refrain from frequenting bars. A bank cashier who becomes known as a gambler may be fired.

Duty to Keep and Render Accounts

The agent must keep accurate financial records, take receipts, and otherwise act in conformity to standard business practices.

Duty to Act Only as Authorized

This duty states a truism but is one for which there are limits. A principal’s wishes may have been stated ambiguously or may be broad enough to confer discretion on the agent. As long as the agent acts reasonably under the circumstances, he will not be liable for damages later if the principal ultimately repudiates what the agent has done: “Only conduct which is contrary to the principal’s manifestations to him, interpreted in light of what he has reason to know at the time when he acts,…subjects the agent to liability to the principal.”[2]

Duty Not to Attempt the Impossible or Impracticable

The principal says to the agent, “Keep working until the job is done.” The agent is not obligated to go without food or sleep because the principal misapprehended how long it would take to complete the job. Nor should the agent continue to expend the principal’s funds in a quixotic attempt to gain business, sign up customers, or produce inventory when it is reasonably clear that such efforts would be in vain.

Duty to Obey

As a general rule, the agent must obey reasonable directions concerning the manner of performance. What is reasonable depends on the customs of the industry or trade, prior dealings between agent and principal, and the nature of the agreement creating the agency. A principal may prescribe uniforms for various classes of employees, for instance, and a manufacturing company may tell its sales force what sales pitch to use on customers. On the other hand, certain tasks entrusted to agents are not subject to the principal’s control; for example, a lawyer may refuse to permit a client to dictate courtroom tactics.

Duty to Give Information

Because the principal cannot be every place at once—that is why agents are hired, after all—much that is vital to the principal’s business first comes to the attention of agents. If the agent has actual notice or reason to know of information that is relevant to matters entrusted to him, they have a duty to inform the principal. This duty is especially critical because information in the hands of an agent is, under most circumstances, imputed to the principal, whose legal liabilities to third persons may hinge on receiving information in timely fashion. Service of process, for example, requires a defendant to answer within a certain number of days; an agent’s failure to communicate to the principal that a summons has been served may bar the principal’s right to defend a lawsuit. The imputation to the principal of knowledge possessed by the agent is strict: even where the agent is acting adversely to the principal’s interests—for example, by trying to defraud their employer—a third party may still rely on notification to the agent, unless the third party knows the agent is acting adversely.

Principal’s Duty to Agent

In this category, we may note that the principal owes the agent duties in contract and tort.

Contract Duties

The fiduciary relationship of agent to principal does not run in reverse—that is, the principal is not the agent’s fiduciary. Nevertheless, the principal has a number of contractually related obligations toward his agent.

General Contract Duties

These duties are analogues of many of the agent’s duties that we have just examined. In brief, a principal has a duty “to refrain from unreasonably interfering with [an agent’s] work.”[3] The principal is allowed, however, to compete with the agent unless the agreement specifically prohibits it. The principal has a duty to inform his agent of risks of physical harm or pecuniary loss that inhere in the agent’s performance of assigned tasks. Failure to warn an agent that travel in a particular neighborhood required by the job may be dangerous (a fact unknown to the agent but known to the principal) could under common law subject the principal to a suit for damages if the agent is injured while in the neighborhood performing her job. A principal is obliged to render accounts of monies due to agents; a principal’s obligation to do so depends on a variety of factors, including the degree of independence of the agent, the method of compensation, and the customs of the particular business. An agent’s reputation is no less valuable than a principal’s, and so an agent is under no obligation to continue working for one who sullies it.

Employment at Will

Under the traditional “employment-at-will” doctrine, an employee who is not hired for a specific period can be fired at any time, for any reason (except bad reasons: an employee cannot be fired, for example, for reporting that his employer’s paper mill is illegally polluting groundwater).

Duty to Indemnify

Agents commonly spend money pursuing the principal’s business. Unless the agreement explicitly provides otherwise, the principal has a duty to indemnify or reimburse the agent. A familiar form of indemnity is the employee expense account.

Exercises

- Describe, in your own words, the difference between a principal and an agent.

- Describe, in your own words, the differences between the duties of a principal and an agent.