4.5 From Apes to Humans

The adaptive radiation of the apes is observable in the fossil record of the Miocene Epoch (~23–5.3 mya). The earliest fossils are from Kenya and Uganda. There were 20 or more genera of apes during the Miocene, and they exhibited a wide range of body sizes and adaptive strategies. These included physiological adaptations (e.g., loss of a tail) and behavioral adaptations (e.g., changes in foraging strategies).

Proconsul is probably the first ape, dating to ~18 mya (see Figure 4.4). As new genera and species evolved, the great apes diversified and spread from Africa to Asia and Europe. The ancestors of the orangutans, Sivapithecues, moved into western and subsequently eastern Asia. Remains in Turkey have been dated to ~12.2 mya. The largest primate that ever lived was the now extinct genus: Gigantopithecus (known primarily from isolated dental and mandibular fragments). Dryopithecini apes moved into Europe during the late Miocene and are generally believed to be the tribe most closely related to the living apes. Unfortunately, little is known about individual genera or species.

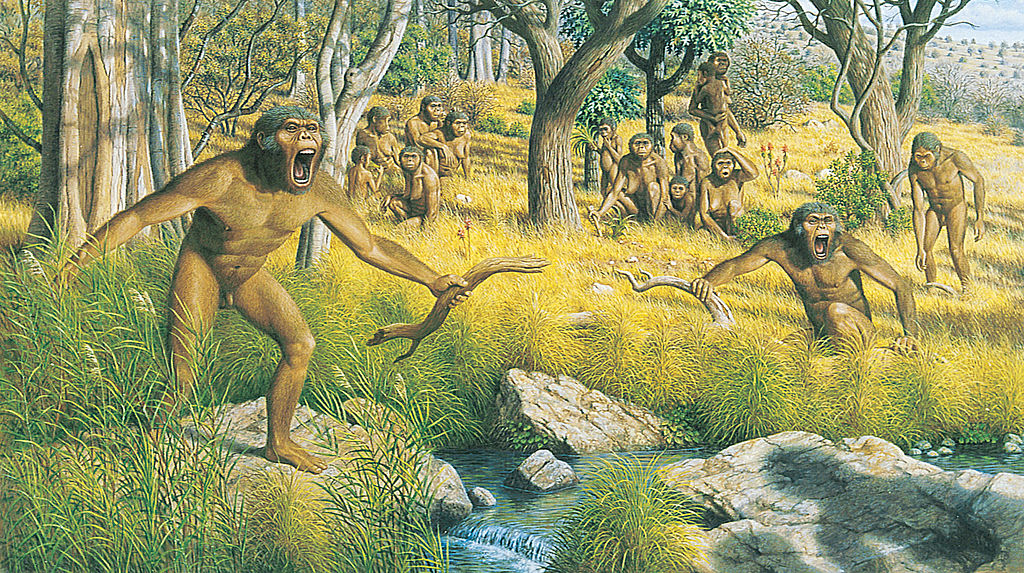

The chimp and human lineages are thought to have diverged by the late Miocene (~7-6.5 mya). Global cooling in the latter part of the Miocene led to the extinction of all ape genera in northern latitudes. Forest cover in Africa was vastly reduced over time due to climatic fluctuations and while most apes went extinct, the newly emerged hominins thrived. Australopithecines became bipedal, freeing their hands for foraging, carrying, and other tasks. Fossil evidence also suggests the formation of social groups more akin to human family structures than those of other apes. This was the beginning of our evolutionary trajectory to the genus Homo.

a rapid increase in the number of species with a common ancestor, characterized by great ecological and morphological diversity.