5.1 Approaches to Studying Cognition

When it comes to studying cognition, there are three primary schools of thought. These are based upon a gradient. One side argues that different species have distinctly different kinds of cognition. The other side emphasizes that all animals have the same type of cognitive capacities in varying degrees. In the middle, the perspective that suggests cognition should be considered in so far as it can make behavioral predictions – but that true understanding of animal others is unobtainable.

Comparative Psychology

In comparative psychology, the focus is usually on research that compares other species on tasks previously used to study humans. This paradigm also holds that intentional mental states and reasoning are the foundation for conscious awareness. As a result, to be “aware” an animal must be able to pass the tests used to study consciousness (defined as reasoning) in humans – and many species do not.

A comparative approach can be useful when attempting to understand how animals currently navigate human worlds. For example, the distal pointing task has been used to study whether other species follow human pointing cues. During this test, a researcher stands at a one end of the space, with an upside-down cup on either side of them. Each cup is baited with food, but only one cup will deliver the tasty treat. With a research participant at the other end of the space, the researcher points to the correct cup. If the participant selects the correct cup more frequently than chance (~60% of the time), they are said to follow the distal point.

Human infants have been shown to engage in intentional communication by the age of 8 months, including reaching and pointing. Masur (1983) was among the first to connect gesturing, signaling to other people, and the transition to words. Using this same task, scientists attempt to determine if and at what age communication from humans is understood by other animals. Many species of passed this test, especially domesticated animals. Yet there are certainly differences. While dogs readily engage in this task, cats often do not test well. Does this mean cats are not attune to human signaling?

Likely not. We certainly wouldn’t say this means cats are not smart. Yet, they may not be smart on this task when compared to humans. In essence, the anthropocentric bias in comparative research can overlook many talents present in other species but missing in ours. So now what?

Ethology

Another approach to studying cognition and animal behavior is ethology. Remember our friend Niko Tinbergen (1907-1988) and his four questions? Tinbergen is considered the father of modern ethology, and much of his work has been embraced by other fields studying the behavior of any species (including humans).

An ethological approach suggests we need to get out of the laboratory setting and study animals, including ourselves, in a more natural setting. This might mean following chimpanzees and other primates through the jungle or pulling out binoculars to watch wolves in Yellowstone Park. It could also mean watching dogs at the dog park or spending time observing a horse show and noting how different handling techniques influence the horses’ behavior. To ethologists, the key is “natural” or “normal” environments eliciting “natural” or “normal” behaviors.

You might notice and wonder, “why does she keep putting natural and normal in quotes?” This is largely because there is a divide in ethology which suggests that domesticated animals and those in captivity cannot be studied. The argument states that, unless an animal lives in the wild, without human intervention, we cannot know for certain what is natural to them?

The counterargument states that living with humans, under some degree of control, is the natural state of domesticated animals. Breeding for the tolerance of human presence is one of the cornerstones of domestication. Therefore, seeing animals, especially domesticates, interacting with humans is not only natural – but evolutionarily relevant.

So, why not simply study all cognition through an ethological lens? One challenge is sample size. Ethological methods can be incredibly time consuming. Scientists may spend an entire field season with a particular group of animals, yet only have data on 15-20 individuals.

This means the key is to find a balance. We need something that uses the tools of comparative psychology with the species-specific understanding of ethology. Enter, Evolutionary Cognition.

Evolutionary Cognition

Frans de Waal is a Dutch born primatologist and ethologist. In his book Are We Smart Enough to Know How Smart Animals Are?, de Waal proposes a new approach. Evolutionary Cognition.

From this perspective, the tools of comparative psychology and ethology work together to create a wholistic approach. By using the controlled, tested methods of comparative psychology with an ethological understanding of the species being tested, de Waal argues we can learn more about what cognitive and emotional capacities are important to a specific species.

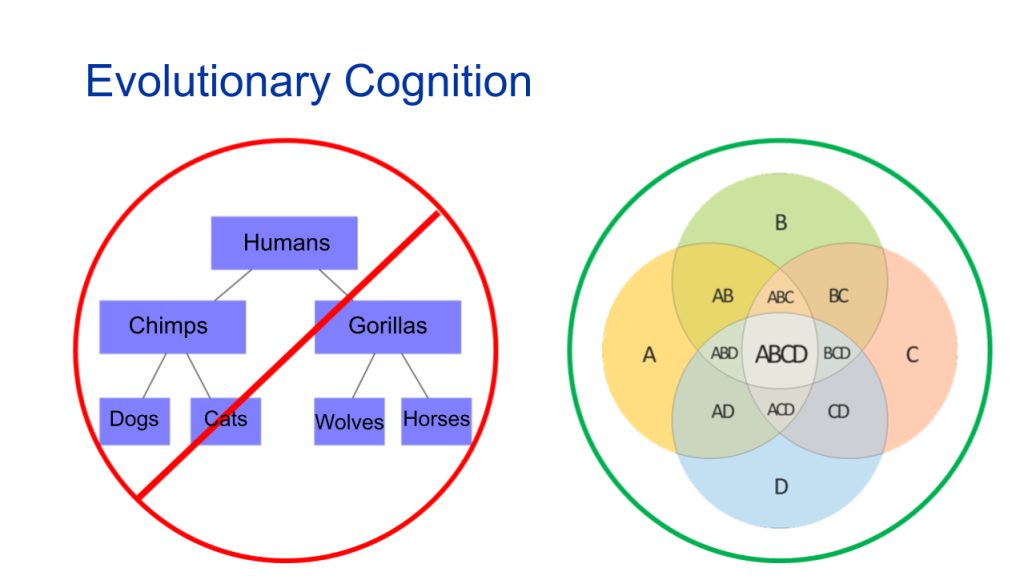

In this way, we move from a hierarchical, anthropocentric testing of cognition to one that looks more like a Venn diagram. Moving away from asking questions like, “are dogs as smart as 18-month-old babies?” or “Do horses follow a human point better than our cousins, the chimpanzees?” to questions like, “Why would a horse need to follow a human point?” We start to consider the environment of evolutionary adaptedness (EEA) of other species and achieve a better understanding of why chimpanzees might need better spatial mapping skills than humans.

In this way, we move ourselves from the top of the hierarchy to a curious observer of the world around us.

the mental action or process of acquiring knowledge and understanding through thought, experience, and the senses.

the study of similarities and differences in behavioral organization among living beings, from bacteria to plants to humans.

the study of human behavior and social organization from a biological perspective.

regarding humankind as the central or most important element of existence, especially as opposed to God or other animals.

the ancestral environment to which a species is adapted.