4.7 Brains, Tools, and Culture

Stone tools and other cultural adaptations are one key in our evolution. Stone tools provide a record of changes in our mental and physical abilities over the past 2+ million years. Homo habilis was once thought to be first hominin tool user, and tool use was thought to be a unique part of the genus Homo. Tool use made us distinctive and gave us the competitive edge over other hominins and other animals. Such a notion occurred before Jane Goodall documented tools use among chimpanzees and well before the documented use of stone tools by some monkeys and other species.

We now know that some species of Australopithecus also used stone tools. Stone tools occur in deposits dated well before the emergence of the first identifiable Homo species. The earliest stone tools date to about 3.3 million years ago in Ethiopia and are likely associated with Australopithecus afarensis.

It is becoming clear that using stone tools was not the most important thing in our evolutionary history, despite some claims to the contrary. Other behaviors could have mattered far more, such as greater cooperation within the group and between groups (something we will discuss in depth in later chapters). This could have had a huge advantage over species that did not cooperate as well – if at all. Chimpanzees do not cooperate well, except for specific circumstances (war and hunting) and look where they are.

H. erectus lived in Africa about 1.5 million years ago. H. erectus’ body anatomy was very similar to ours, though there are key differences in the skull. Though their brain was larger than previous species, the H. erectusbrain was smaller than that of modern humans and evidently organized differently because it lacked the greatly expanded frontal lobe seen in modern humans. Their skull was long, low, and thickly walled, narrowing behind the eyes. H. erectus’ skull also had pronounced brow ridges and a low ridge running along the crest of the skull. Another ridge of bone ran horizontally along the back of the skull.

Oldowan Technology

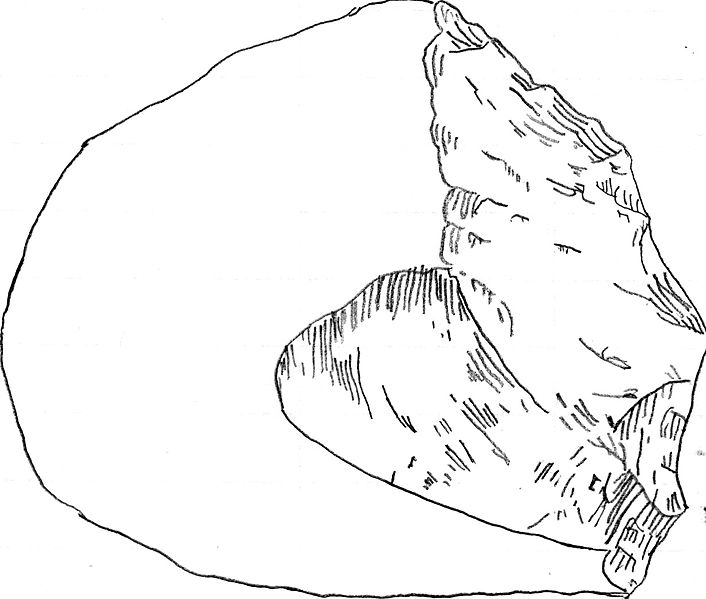

The first recognizable earliest stone tools associated with the genus Homo, thus representing the most diagnostic and earliest of human culture, is the Oldowan technology, named after Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania. Oldowan technology consists of pebbles about the size of a baseball or softball with flakes removed from them on one end and the simple flakes detached from such cobbles. They are associated with H. habilis and H. rudolfensis. A simple technology like this persisted for a very long time and even fully modern humans would create simple Oldowan-looking tools to expediate tasks.

Throughout her research in Olduvai Gorge, Mary Leakey (1913-1996) defined Oldowan technology as primarily consisting of pebble “choppers.” Today these are defined as “cores” and they comprise less than 30% of a total assemblage at the various sites; flakes detached from those cores comprise 70% or more. Mary Leakey considered the cores to be the true tools and the flakes or debitage to be manufacturing debris. Flakes were detached by striking cores at the proper angle using a hard hammerstone for direct percussion. These days archaeologists recognize that the flakes are in many cases also tools, used in cutting through animal hide and likely other materials, slicing off meat, and scraping. Many of the stone cores likely also functioned as tools like Mary Leaky thought, such as for cracking open marrow-rich long bones.

Acheulean Tradition

Acheulean technology consists of more refined stone tools than those made and used by H. habilis. Acheulean technology emphasized what archaeologists refer to as bifaces, which simply means cores that are flaked on two sides to make them somewhat flat and thin. The Acheulean bifaces, often referred to as handaxes, are somewhat teardrop-shaped with a sharp point and sharp adjacent lateral edges. The rounded “back” of the tool might be less flaked or have blunt edges and is assumed to be where Homo erectus held them. These bifaces are associated with Homo erectus, but also later Homo species, and the bifaces become more refined through time.

As with Oldowan Tradition, archaeologists have traditionally emphasized the core tools, those handaxes, as the being the focus of the technology. But, just as with Oldowan the flakes that got detached while making the bifaces were likely important tools as well, at least the larger flakes. There are also hypotheses that H. erectus was demonstrating skill and artistry when making these tools. Many of them are incredibly symmetrical given the lack of machinery or measuring tools. Yet others have inclusions in the stone around which the tool appears to be made.

Mousterian Technology

The Mousterian flaked technology is one that clearly emphasizes flakes more than cores. The core was well formed by detaching a series of preparatory flakes, and the resulting shape of the prepared core would allow for useful flakes to be detached. This process would continue until the core was too small to produce quality flakes. The number of iterations depended on the size of the original chunk of raw material, with large pieces allowing for the removal of more such desirable flakes.

This method of making flakes from prepared cores is also known as Levallois (lev-all-WA) technique. It was widely practiced by H. neanderthalensis, as well as early H. sapiens, and took considerable planning, hand-eye coordination, and flintknapping skill. The preparatory flake detachments to shape the core and then to create the proper surface (platform) for striking the core, were essential to creating desired flakes.

For a more extensive overview of these transitions, I encourage you to read “Chapter 5: The Genus Homo and the Emergence of Us” in Introduction to Anthropology by Jennifer Hasty, David G. Lewis, and Marjorie M. Snipes.

Interacting with the Smithsonian Institute

Visit the Human Characteristics: What Does it Mean to Be Human, from the Smithsonian Institute. What can you learn about the importance of tool use and human evolution? How did humans change the world as we evolved?

Additionally, the Human Evolution Interactive Timeline is a great way to visualize these changes. Use the “magnifier” tool on the bottom left of the page to zoom in for more detail.

the process of working together to the same end.

each of the paired lobes of the brain lying immediately behind the forehead, including areas concerned with behavior, learning, personality, and voluntary movement.

a type of prehistoric stone implement flaked on both faces.