7.2 Types of Adaptations

Once an adaptation occurs, it generally falls into one of three main types: structural, physiological, or behavioral. We unpack these below.

Structural Adaptations

Structural adaptations are those that change the physical, outward features of an organism or species. A structural adaptation may result in an animal flying, swimming faster, running longer, or being more capable of hunting prey.

We’ve all seen a cat’s eyes glow in the dark or reflect a flash of light. This green, blue, or gold glow of the eyes is the result of a structural adaptation called the tapetum lucidum. This reflective layer is found within the eyes of many nocturnal animals and twilight hunters. By reflecting visible light from the retina to photoreceptors in the eye, the tapetum lucidum makes it easier for these animals to see in the dark.

Haplorrhines lost their tapetum lucidum in exchange for acute color vision. Because most haplorrhines forage during the day, they no longer needed the enhancement of light to see at night. Instead, this space became filled with additional photoreceptors, allowing us to see minute differences in the color of fruits and other potential food sources – letting us know if an item was ripe to eat or likely to make us sick.

Another example of a structural adaptation is the duck’s webbed foot. At some point in evolutionary history, the mutation for webbed feet arose in the ancestors of these aquatic birds. This mutation enhanced speed and accuracy of swimming and diving, eventually being positively selected as a trait. The structural adaptation remains valuable to many ducks, geese, and other species of aquatic fowl.

Physiological Adaptations

Physiological adaptations are those that result in changes in body chemistry, metabolism, or other internal processes that are crucial to survival and reproduction. These may include, but are not limited to, the toxins produced by some plants, hormones like oxytocin that promote bonding and sociality, and variations in the digestive microbiome that allow for a species to eat particular foods.

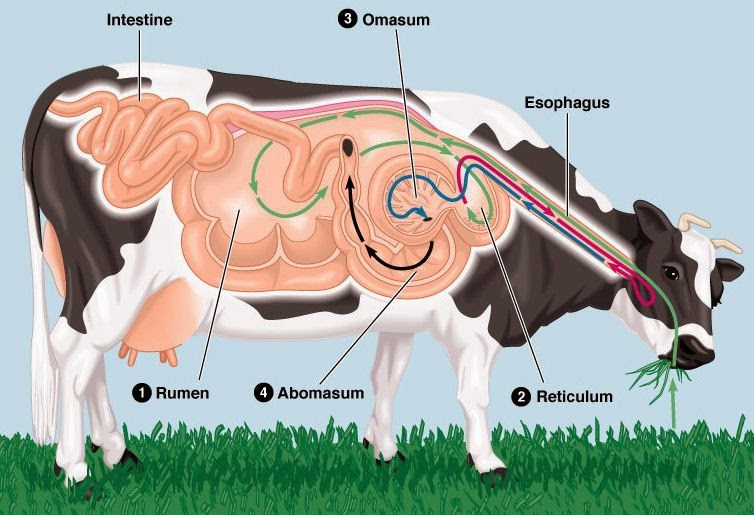

A common example of a physiological adaptation is the four-compartment stomach of most ruminants. Consisting of the rumen, the reticulum, the omasum, and the abomasum, these multi-compartment stomachs allow ruminants to digest low quality plant sources (e.g., grass, hay) and still extract the most calories, vitamins, and minerals from the food before it passes to waste. This occurs via a fermentation process aided by the microbiome of the ruminant’s stomach, resulting in valuable fatty acids, B vitamins, vitamin K, and amino acids.

Most people think of cows when considering ruminants. However, it is important to know that there are many ruminants including sheep and goats, deer, antelope, elk, camels, and alpacas. It is also important to note that ruminants do not have multiple stomachs. Rather, they have one stomach with multiple compartments that each contribute to the process of digesting food.

Behavioral Adaptations

Last, but certainly not least, are behavioral adaptations. A behavioral adaptation changes how an organism acts, behaves, or interacts with their environment. There are numerous examples of behavioral adaptations, from bird and whale song, to Japanese macaques who wash sweet potatoes in nearby water before eating them.

Behavioral adaptations are everywhere. Animals that hide from predators rather than running into danger are expressing a behavioral adaptation for caution. Wolf pups that greet their elders by licking muzzles, wiggling, and yipping are doing so because this greeting solidifies their relationships – and encourage adult wolves to regurgitate breakfast for the young. Even the fact that you are sitting somewhere, in front of your computer, reading this chapter is a behavioral adaptation – we will get to that in a minute.

The following video discusses how whale song varies across populations. Yet, this variation is not static. As different pods of whales meet each other, they share parts of their songs. These new lines may be incorporated into the existing song, resulting in a type of “sampling” from each other’s music. This is an example of a behavioral adaptation that remains fluid to environmental and social interactions. We might even call this “culture.”

physical features of an organism that enable them to survive and be competitive in their environment.

a layer at the back of the eyeball containing cells that are sensitive to light and that trigger nerve impulses that pass via the optic nerve to the brain, where a visual image is formed.

a structure in a living organism, especially a sensory cell or sense organ, that responds to light falling on it.

changes to internal body processes that regulate and maintain homeostasis for an organism to survive in the environment in which it exists.

an even-toed ungulate mammal that chews the cud regurgitated from its rumen. The ruminants comprise the cattle, sheep, antelopes, deer, giraffes, and their relatives.

changes to the way an animal responds, usually to some type of external stimulus, in order to survive.

the ability to learn and transmit behaviors through processes of social or cultural learning; increasingly seen as a process, involving the social transmittance of behavior among peers and between generations.