16 Ancient Greece

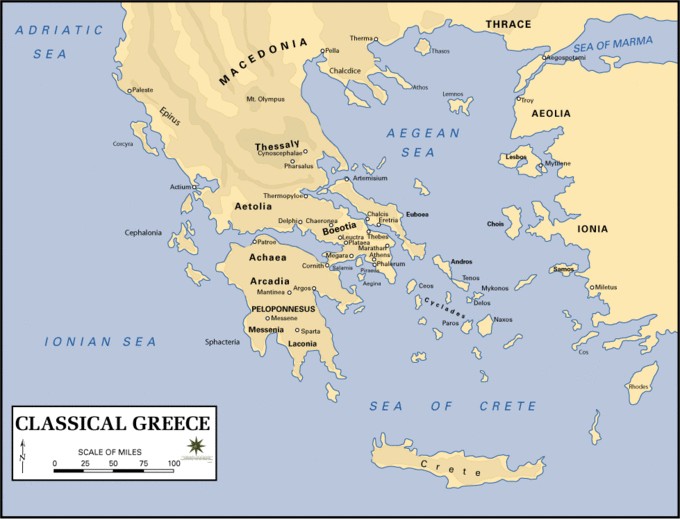

Introduction to Ancient Greece

Ancient Greek culture spans over a thousand years, from the earliest civilizations to the cultures that became the Ancient Greeks.

Key Points

- Ancient Greek culture is noted for its government, art, architecture, philosophy, and sports, all of which became foundations for modern western society. It was admired and adopted by others, including Alexander the Great and the Romans, who helped spread Greek culture around the world. Before Greek culture took root in Greece, early civilizations thrived on the Greek mainland and the Aegean Islands. The fall of these cultures and the aftermath, known as the Dark Age, is believed to be the time when the Homeric epics were first recited.

- Greek culture began to develop during the Geometric, Orientalizing, and Archaic periods, which lasted from 900 to 480 BCE. During this time the population of city-states began to grow, Panhellenic traditions were established, and art and architecture began to reflect Greek values.

- The Early, High, and Late Classical periods in Greece occurred from 480 to 323 BCE. During these periods, Greece flourished and the polis of Athens saw its Golden Age under the leadership of Pericles. However, city-state rivalries lead to wars, and Greece was never truly stable until conquered.

- The Hellenistic period in Greece is the last period before Greek culture becomes a subset of Roman hegemony. This period occurs from the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE, to the Greek defeat at the Battle of Actium in 30 BCE. It marks the spread of Greek culture across the Mediterranean.

Key Terms

- polis: A city, or a city-state. Its plural is poleis.

Ancient Greek Culture

Ancient Greek culture covers over a thousand years of history, from the earliest civilizations in the area to the cultures that became the Ancient Greeks. Following a Greek Dark Age, Greece once more flourished and developed into the ancient culture that we recognize today.

Greek culture is based on a series of shared values that connected independent city- states throughout the region and expanded as far north as Mount Olympus. Greek society was insular, and loyalties were focused around one’s polis (city-state). Greeks considered themselves civilized and considered outsiders to be barbaric.

While Greek daily life and loyalty was centered on one’s polis, the Greeks did create leagues, which vied for control of the peninsula, and were able to unite together against a common threat (such as the Persians).

Greek culture is focused on their government, art, architecture, philosophy, and sport. Athens was intensely proud of its creation of democracy, and citizens from all poleis (city-states) took part in civic duties. Cities commissioned artists and architects to honor their gods and beautify their cities.

As a religious people, the Greeks worshipped a number of gods through sacrifices, rituals, and festivals.

Review: Bronze Age and Proto-Greek Civilizations

Cycladic Civilization

During the Bronze Age, several distinct cultures developed around the Aegean. The Cycladic civilization, around the Cyclades Islands, thrived from 3,000 to 2,000 BCE. Little is known about the Cycladic civilization because they left no written records. Their material culture is mainly excavated from grave sites, which reveal that the people produced unique, geometric marble figures.

Minoan Civilization

The Minoan civilization stretches from 3700 BCE until 1200 BCE and thrived during their Neopalatial period (from 1700 to 1400 BCE), with the large-scale building of communal palaces. Numerous archives have been discovered at Minoan sites; however their language, Linear A, has yet to be deciphered. The culture was centered on trade and production, and the Minoans were great seafarers on the Mediterranean Sea.

Mycenaean Civilization

A proto-Greek culture known as the Mycenaeans developed and flourished on the mainland, eventually conquering the Aegean Islands and Crete, where the Minoan civilization was centered. The Mycenaeans developed a fractious, war-like culture that was centered on the authority of a single ruler. Their culture eventually collapsed, but many of their citadel sites were occupied through the Greek Dark Age and rebuilt into Greek city-states.

The Dark Age

From around 1200 BCE, the palace centers and outlying settlements of the Mycenaeans’ culture began to be abandoned or destroyed. By 1050 BCE, the recognizable features of Mycenaean culture had disappeared. Many explanations attribute the fall of the Mycenaean civilization and the collapse of the Bronze Age to climatic or environmental catastrophe, combined with an invasion by the Dorians or by the Sea Peoples, or to the widespread availability of edged weapons of iron, but no single explanation fits the available archaeological evidence.

This two- to three-century span of history is also known as the Homeric Age. It is believed that the Homeric epics The Iliad and The Odyssey were first recited around this time.

Ancient Greece after the Dark Ages

The Geometric and Orientalizing Periods

The Geometric period (c. 900–700 BCE), which derives its name from the proliferation of geometric designs and rendering of figures in art, witnessed the emergence of a new culture on the Greek mainland. The culture’s change in language, its adaptation of the Phoenician alphabet, and its new funerary practices and material culture suggest the ethnic population changed from the mainland’s previous inhabitants, the Mycenaeans. During this time, the new culture was centered on the people and independent poleis, which divided the land into regional populations. This period witnessed a growth in population and the revival of trade.

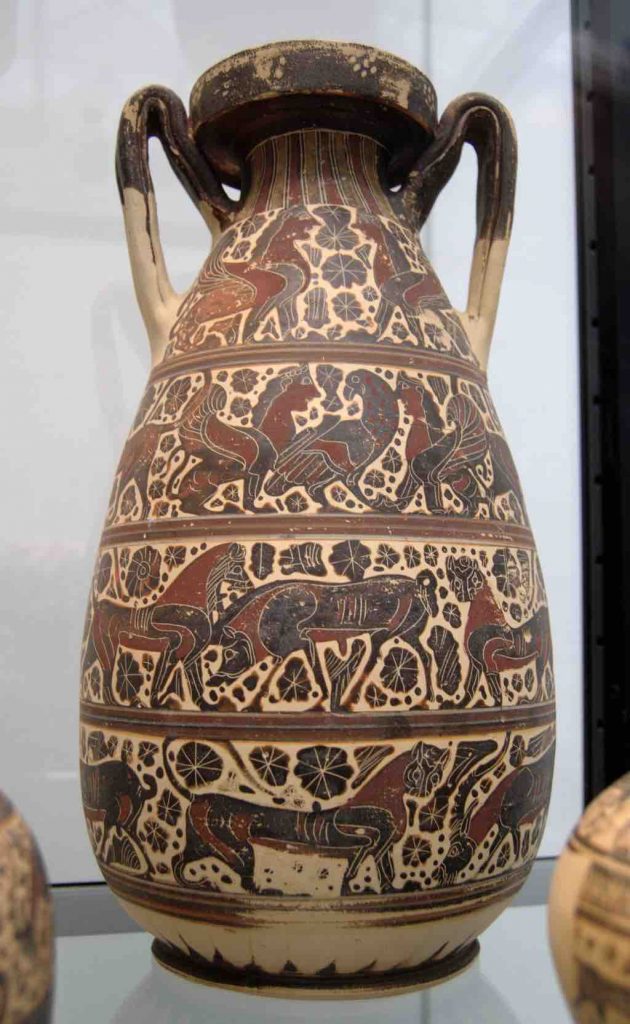

The Orientalizing period (c. 700–600 BCE) is named for the cultural exchanges the Greeks had with Eastern, or Oriental civilizations. During this time, international trade began to flourish. Art from this period reflects contact with locations such as Egypt, Syria, Assyria, Phoenicia, and Israel.

Archaic Greece

Greece’s Archaic period lasted from 600 to 480 BCE, in which the Greek culture expanded. The population in Greece began to rise and the Greeks began to colonize along the coasts of the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. The poleis at this time were typically ruled by a single ruler who commanded the city by force. For the city of Athens, this led to the creation of democracy. Several city-states emerged as major powers, including Athens, Sparta, Corinth, and Thebes. These poleis were often warring with each other and formed coalitions to gain power and allies. The Persian invasion of Greece in 480 BCE marked the end of the Archaic period.

Classical Greece

The era of Classical Greece began in 480 BCE with the sacking of Athens by the Persians. The Persian invasion of Greece, first lead by Darius I and then by his son Xerxes, united Greece against a common enemy.

With the defeat of the Persian threat, Athens became the most powerful polis until the start of the Peloponnesian War in 431 BCE. These wars continued on and off until 400 BCE. While marred by war, the Classical period saw the height of Greek culture and the creation of some of Greece’s most famous art and architecture. However, peace and stability in Greece was not achieved until it was conquered and united by Macedonia under the leadership of Philip II and Alexander the Great in the mid-third century BCE.

Late Classical Greece

After the Peloponnesian wars a new style of sculpture seemed to emerge. Figures became taller in proportion and gods exhibited a new moral laxity unseen in earlier periods. For the first time, goddesses were pictured nude, or semi-nude.

Hellenistic Greece

The Hellenistic period began with the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE and ended with the Roman victory at the Battle of Actium in 30 BCE. Greece poleis spent this time under the hegemony of foreign rulers, first the Macedons and then the Romans, starting in 146 BCE.

New centers of Hellenic culture flourished through Greece and on foreign soil, including the cities of Pergamon, Antioch, and Alexandria—the capitals of the Attalids, Seleucids, and Ptolemies.

The Ancient Greek Gods and Their Temples

Greek religion played a central and daily role in the life of ancient Greeks, and group worship was centered on the temple and cult sites.

Greek religious traditions encompassed a large pantheon of gods, complex mythologies, rituals, and cult practices. Greece was a polytheistic society and looked to its gods and mythology to explain natural mysteries as well as current events. Religious festivals and ceremonies were held throughout the year, and animal sacrifice and votive offerings were popular ways to appease and worship the gods. Religious life, rituals, and practices were one of the unifying aspects of Greece across regions and poleis (cities, or city-states, such as Athens and Sparta).

Greek Gods

Greek gods were immortal beings who possessed human-like qualities and were represented as completely human – albeit perfectly formed – in visual art. They were moral and immoral, petty and just, and often vain. The gods were invoked to intervene and assist in matters large, small, private and public.

City-states claimed individual gods and goddess as their patrons. Temples and sanctuaries to the gods were built in every city. Many cities became cult sites due to their connection with a god or goddess and specific myths. For instance, the city of Delphi was known for its oracle and sanctuary of Apollo, because Apollo was believed to have killed a dragon that inhabited Delphi.

The history of the Greek pantheon begins with the primordial deities Gaia (Mother Earth) and Uranus (Father Sky), who were the parents of the first of twelve giants known as Titans. Among these Titans were six males and six females.

The Olympian Gods

Best known among the pantheon are the twelve Olympian gods and goddesses who resided on Mt. Olympus in northern Greece. Violence and power struggles were common in Greek mythology, and the Greeks used their mythologies to explain their lives around them, from the change in seasons to why the Persians were able to sack Athens.

The traditional pantheon of Greek gods includes:

- Zeus, the king of gods and the ruler of the sky.

- Zeus’ two brothers, Poseidon (who ruled over the sea) and Hades (who ruled the underworld).

- Zeus’s sister and wife, Hera, the goddess of marriage, who is frequently jealous and vindictive of Zeus’s other lovers.

- Their sisters Hestia, the goddess of the hearth, and Demeter, the goddess of grain and culture.

- Zeus’s children:

- Athena (goddess of warfare and wisdom).

- Hermes (a messenger god and god of commerce).

- the twins Apollo (god of the sun, music, and prophecy) and Artemis (goddess of the hunt and of wild animals).

- Dionysos (god of wine and theatre).

- Aphrodite (goddess of beauty and love), who was married to Hephaestus (deformed god of the forge).

- Ares (god of war and lover of Aphrodite) are also part of the traditional pantheon.

- Hephaestus was in some mythologies the son of Zeus while in others the fatherless son of Hera.

Heroes

Heroes, who were often demigods, were also important characters in Greek mythology. The two most important heroes are Perseus and Hercules.

Perseus

Perseus is known for defeating the Gorgon, Medusa. He slew her with help from the gods: Athena gave him armor and a reflective shield, and Hermes provided Perseus with winged sandals so he could fly.

Hercules

Hercules was a strong but unkind man, a drunkard who conducted huge misdeeds and social faux pas. Hercules was sent on twelve labors to atone for his sins as punishment for his misdeeds. These deeds, and several other stories, were often depicted in art, on ceramic pots, or on temple metopes. The most famous of his deeds include slaying both the Nemean Lion and the Hydra, capturing Cerberus (the dog of the underworld), and obtaining the apples of the Hesperides.

Theseus

A third hero, Theseus, was an Athenian hero known for slaying King Minos’s Minotaur. Other major heros in Greek mythology include the warriors and participants of the Trojan War, such as Achilles, Ajax, Odysseus, Agamemnon, Paris, Hector, and Helen.

Hero cults were another popular form of Greek worship that involved the honoring of the dead, specifically the dead heroes of the Trojan War. The sites of hero worship were usually old Bronze Age sites or tombs that the ancient Greeks recognized as important or sacred, which they then connected to their own legends and stories.

Sacred Spaces

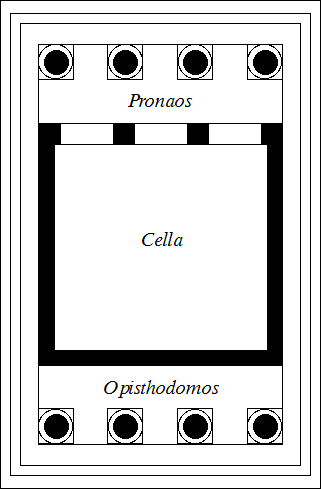

Greek worship was centered on the temple. The temple was considered the home of the god, and a cult statue of the god would be erected in the central room, or the naos. Temples generally followed the same basic rectangular plan, although a round temple, known as a tholos, were used at some sites in starting in the Classical period.

Temples were oriented east to face the rising sun. Patrons would leave offerings for the gods, such as small votives, large statues, libations or costly goods. Due to the wealth dedicated to the gods, the temples often became treasuries that held and preserved the wealth of the city. Greek temples would be extensively decorated, and their construction was a long and costly endeavor.

Rituals and animal sacrifices in honor of the god or goddess would take place outside, in front of the temple. Rituals often included a large number of people, and sacrifice was a messy business that was best done outdoors. The development and decoration of temples is a primary focus in the study of Greek art and culture.

The Greek Geometric Period

The Geometric period in Greek art is distinguished by a reliance on geometric shapes to create human and animal figures as well as abstract décor.

Key Points

- The Geometric period marked the end of Greece’s Dark Age and lasted from 900 to 700 BCE.

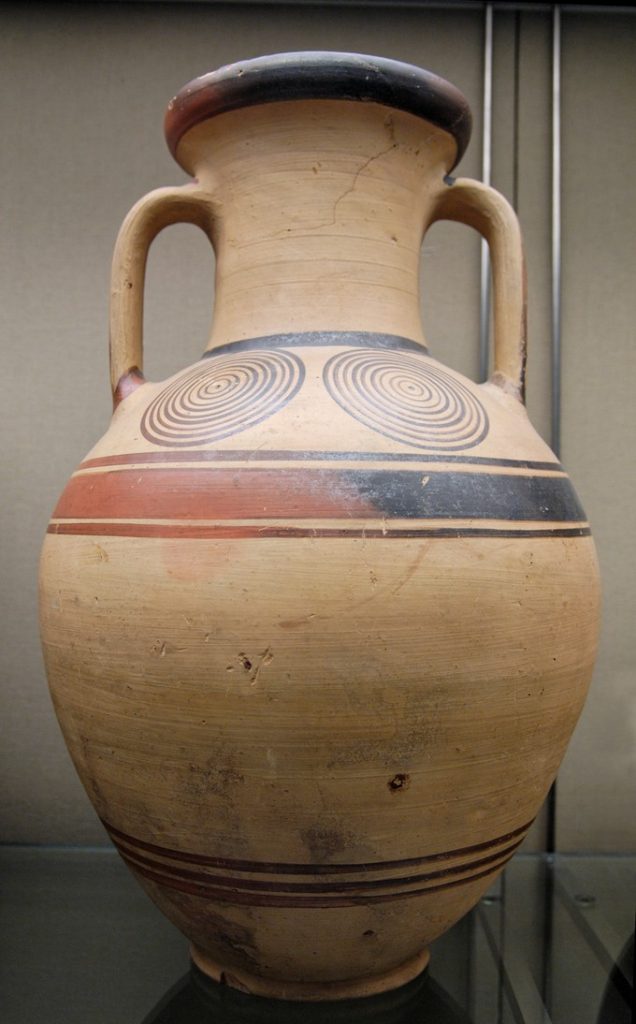

- The Geometric period derives its name from the dominance of geometric motifs in vase painting. Monumental kraters and amphorae were made and decorated as grave markers. These vessels are characteristic of Geometric vase painting during this period.

- The most famous vessels from this period uses a technique called horror vacui, in which every space of the surface is filled with imagery.

Key Terms

- horror vacui: From the Latin, fear of empty space, it is a style of painting where the entire surface of a space is filled with patterns and figures.

- amphora: A two-handled jar with a narrow neck that was used in ancient times to store or carry wine or oils.

- krater: An ancient Greek vessel for mixing water and wine.

Geometric Pottery

In the eleventh century BCE, the citadel centers of the Mycenaeans were abandoned and Greece fell into a period with little cultural or social progression. Signs of civilization including literacy, writing, and trade were lost and the population on mainland Greece plummeted. During the Proto-Geometric period (1050–900 BCE), painting on ceramics began to re-emerge. These vessels were only decorated with abstract geometric shapes adopted from Mycenaean pottery. Ceramicists began using the fast wheel to create vessels, which allowed for new, more monumental objects.

In the Geometric period that followed, figures once more became present on the vessel. The period lasted from 900 to 700 BCE and marked the end of the Greek Dark Ages. A new Greek culture emerged during this time. The population grew, trade began once more, and the Greeks adopted the Phoenician alphabet for writing. Unlike the Mycenaeans, this culture was more focused on the people of the polis, which is reflected in the art of this period. The period gets its name from the reliance on geometric shapes and patterns in its art, and even their use in depicting both human and animal figures.

Athens

The city of Athens became the center for pottery production. A potter’s quarter in the section of the city known as the Kerameikos was located on either side of the Dipylon Gate, one of the city’s west gates. The potters lived and work inside the gate in the city, while outside the gate, along the road, was a large cemetery. In the Geometric period, monumental-sized kraters and amphorae up to six feet tall were used as grave markers for the burials just outside the gate. Kraters marked male graves, while amphorae marked female graves.

The Dipylon Master, an unknown painter whose hand is recognized on many different vessels, displays the great expertise required for decorating these funerary markers. The vessels were first thrown a wheel, an important technological development at the time, before painting began. Both the Diplyon Krater and Dipylon Amphora demonstrate the main characteristics of painting during this time. For one, the entire vessel is decorated in a style known as horror vacui, a style in which the entire surface of the medium is filled with imagery. A decorative meander is on the lip of the krater and on many registers of the amphora. This geometric motif is constructed from a single, continuous line in a repeated shape or motif. The main scene is depicted on the widest part of the pot’s body. These scenes relate to the funerary aspect of the pot and may depict mourners, a prothesis (a ritual of laying the body out and mourning), or even funerary games and processions.

On the Dipylon Krater, two registers depict a processional scene, an ekphora, (the transportation of the body to the cemetery) and the prothesis. The dead man of the prothesis scene is seen on the upper register. He is laid out on a bier and mourners, distinguished by their hands tearing at their hair, surround the body. Above the body is a shroud, which the artist depicts above and not over the body in order to allow the viewer to see the entirety of the scene.

On the register below, chariots and soldiers form a funerary procession. The soldiers are identified by their uniquely shaped shields. The Dipylon Amphora depicts just a prothesis in a wide a register around the pot.

In both vessels, men and women are distinguished by protruding triangles on their chest or waist to represent breasts or a penis. Every empty space in these scenes is filled with geometric shapes—M’s, diamonds, starbursts—demonstrating the Geometric painter’s horror vacui.

Sculpture in the Greek Geometric Period

Although derived from geometric shapes, the Ancient Greek sculptures of the Geometric period show some artistic observation of nature.

Key Points

- Geometric sculptures are primarily small scale and made of bronze, terra cotta, or ivory. The bronze figures were produced using the lost-wax method of casting.

- The human and animal figures produced during this period have geometric features, although the legs on humans appear relatively naturalistic.

- Geometric bronzes were typically left as votive offerings at shrines and sanctuaries, such as those at Delphi and Olympia.

- Horses came to symbolize wealth due to the high costs of their upkeep.

Key Terms

- votive: A type of offering deposited within a religious site without the purpose of display or retrieval.

The ancient Greek sculptures of the Geometric period, although derived from geometric shapes, bear evidence of an artistic observation of nature in some circumstances. Small-scale sculptures, usually made of bronze, terra cotta, or ivory, were commonly produced during this time. Bronzes were made using the lost-wax technique, probably introduced from Syria, and were often left as votive offerings at sanctuaries such as Delphi and Olympia.

Human Figures

The human figures are made of a triangle as a torso that supports a bulbous head with a triangular chin and nose. Their arms are cylindrical, and only their legs have a slightly more naturalistic shape. These attributes can be seen in a small sculpture of a seated man drinking from a cup that displays the typical modeling figures as simple, linear forms that enclose open space. Especially noteworthy are his elongated arms that mirror the dimensions of his legs.

A relatively naturalistic rendering of human legs is also evident in Man and Centaur, also known as Heracles and Nessos (c. 750–730 BCE). Without the equine back and hind legs, the centaur portion of the sculpture is a shorter man with human legs. Like the seated man above, the two figures feature elongated arms, with the right arm of the centaur forming one continuous line with the left arm of the man. While the seated man appears to be clean shaven, the figures in Man and Centaur wear beards, which usually symbolized maturity. The hollow eye sockets of the figure of the man probably once held inlay for a more realistic appearance.

Animal Figures

Animals, including bulls, deer, horses, and birds, were also based in geometry. Horse figurines were commonly used as offerings to the gods. The animals themselves became symbols of wealth and status due to the high cost of keeping them. Equine bodies may be described as rectangles pinched in the middle with rectangular legs and tail and are similar in shape to deer or bulls.

The heads of these mammals are more distinctive, as the horse’s neck arches, while the bull and deer have cylindrical faces distinguished by horns or ears. While the animals and people are based in basic geometric shapes, the artists clearly observed their subjects in order to highlight these distinguishing characters.

The Orientalizing Period

Ceramics in the Orientalizing Period

The Orientalizing Period followed the Geometric period and lasted for about a century, from 700 to 600 BCE. This period was distinguished by international influences—from the Ancient Near East, Egypt, and Asia Minor—each of which contributed a distinctive Eastern style to Greek art. The close contact between cultures developed from increasing trade and even colonization. Motifs, creatures, and styles were borrowed from other cultures by the Greeks, who transformed them into a unique Greek–Eastern mix of style and motifs.

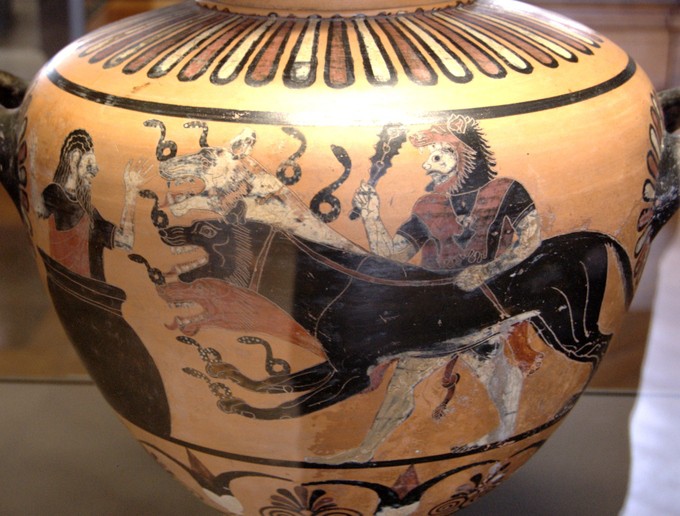

Corinthian Pottery

During the Orientalizing period in Corinth human figures were rarely seen on vases. Animals such as lions, griffins, sphinxes, and sirens were depicted instead. Palmettes and lotus blossoms were used instead of geometric patterns to fill empty space, although on some vessels negative space became more prominent. This oriental black figure style originated in the city of Corinth, spread to Athens, and was exported throughout Greece.

Black Figure Painting

The Corinthians developed the technique of black figure painting during this period. Black figure pottery was carefully constructed and fired three different times to produce the unique red and black colors on each vase.

The black color came from a slip painted onto the vessel, after which incised lines were drawn on to outline and detail the figures. Additionally, red and white pigments could be added for more color or to differentiate details. The unpainted portions of the vase would remain the original red-orange color of the pot. The full effect of this style of painting would not have been seen until after the vase emerged from its firings in the kiln. As the style spread, the subject matter changed from strictly Near Eastern animals to scenes from Greek mythology and everyday life.

The heat of the kiln in which the pottery was fired and the length of time each firing occupied was essential in the final look of the piece. The sophistication of the work in a culture without thermometers or clocks suggests the skill of the Greek artists.

Sculpture in the Greek Orientalizing Period

Sculpture produced during the Orientalizing period shares stylistic attributes with sculpture produced in Egypt and the Near East.

Key Points

- Sculpture during this time was influenced by Egyptian and Near Eastern artistic conventions. Rigid, plank-like bodies, as well as its reliance on pattern to depict texture, characterized Greek sculpture in the Orientalizing period.

- The Daedalic style, named for the mythical inventor Daedalus, refers the use of patterning and geometric shapes (reminiscent of the Geometric period ) during the seventh century BCE.

- The differences between the Lady of Auxerre and the Mantiklos Apollo demonstrate the early establishment of traditional social expectations of the sexes in ancient Greek culture.

Key Terms

- kore: A sculpture of a young woman from pre-Classical Greece.

- Daedalic: A style of sculpture during the Greek Orientalizing period noted for its use of patterns to create texture, as well as its reliance on geometric shapes and stiff, rigid bodily postures.

The Orientalizing Period lasted for about a century, from 700 to 600 BCE. This period was distinguished by international influences, from the Ancient Near East, Egypt, and Asia Minor, each of which contributed a distinctive Eastern style to Greek art. The close contact between cultures developed from increasing trade and even colonization.

Styles were borrowed from other cultures by the Greeks who transformed them into a unique Greek-Eastern mix of style and motifs. Male and female sculptures produced during this time share interesting similarities, but also bear differences that inform the viewer about society’s expectations of men and women.

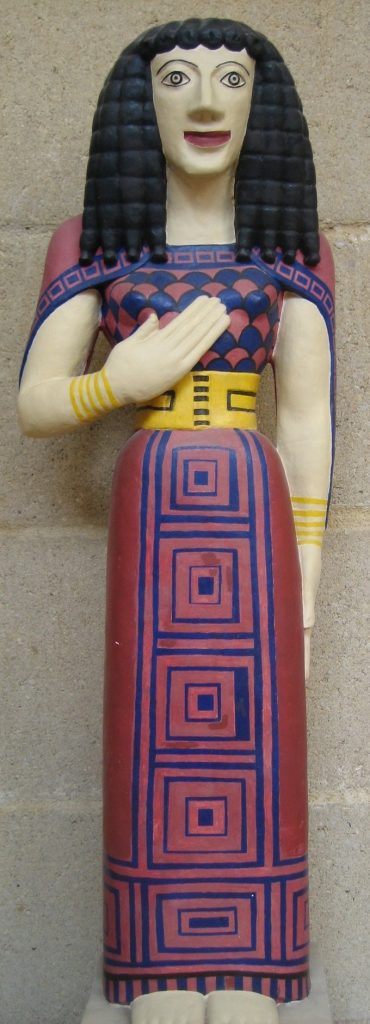

The Lady of Auxerre

A small limestone statue of a kore (maiden), known as the Lady of Auxerre (650– 625 BCE), from Crete demonstrates the style of early Greek figural sculptures. This style is known as Daedalic sculpture, named for the mythical creator of King Minos’s labyrinth, Daedalus. The style combines Ancient Near Eastern and Egyptian motifs.

The Lady of Auxerre is stocky and plank-like. Her waist is narrow and cinched, like the waists seen in Minoan art. She is disproportionate, with long rigid legs and a short torso. A dress encompasses nearly her entire body—it tethers her legs together and restricts her potential for movement. The rigidity of the body recalls pharaonic portraiture from Ancient Egypt.

Her head is distinguished with large facial features, a low brow, and stylized hair. The hair appears to be braided, and falls down in rigid rows divided by horizontal bands. This style recalls a Near Eastern use of patterns to depict texture and decoration, as in the bronze Akkadian head of Sargon.

Her face and hair are reminiscent of the Geometric period. The face forms an inverted triangle wedged between the triangles formed be the hair that frames her face. Traces of paint tell us that this statue would have originally been painted with black hair and a dress of red and blue with a yellow belt.

The Greek Archaic Period

Sculpture during the Archaic period became increasing naturalistic, although this varies depending on the gender of the subject.

Key Points

- Dedicatory male kouroi figures were originally based on Egyptian statues and over the Archaic period these figures developed more naturalistic nude bodies. The athletic body was an ideal form for a young Greek male and is comparable to the ideal body of the god Apollo.

- Instead of focusing on the body, female korai statues were clothed and throughout the Archaic period artists spent more time elaborating on the detailed folds and drapery of a woman’s clothing. This reflected the Greek ideals for women, who were supposed to be fully clothed, modest, and demure.

- To add an additional naturalistic element to the body, the typical Archaic smile was added to both male and female statues. While today the smile seems false, to the ancient Greeks it added a level of realism.

- Pedimental sculpture in the Archaic period was often scaled to fit into the space of the pediment and served an apotropaic instead of a decorative function.

- Pedimental sculptures from the Temple of Aphaia at Aegina show a gradual move toward the naturalism of the Classical style that followed the Archaic.

Key Terms

- Archaic smile: A stylized expression used in sculpture from 600 to 480 BCE to suggest a sense of lifelikeness in the subject.

- peplos: An Ancient Greek garment, worn by women, made of a tubular piece of cloth that is folded back upon itself halfway down, until the top of the tube is worn around the waist, and the bottom covers the legs down to the ankles; the open top is then worn over the shoulders, and draped, in folds, down to the waist.

- apotropaic: Intended to ward off evil.

- kouros: A sculpture of a naked youth in Ancient Greece; the male equivalent of a kore.

- kore: An Ancient Greek statue of a woman, portrayed standing, usually clothed, painted in bright colors, and having an elaborate hairstyle.

- chiton: A loose, woolen tunic, worn by both men and women in Ancient Greece.

Sculpture in the Archaic Period

Sculpture in the Archaic Period developed rapidly from its early influences, becoming more natural and showing a developing understanding of the body, specifically the musculature and the skin. Close examination of the style’s development allows for precise dating.

Most statues were commissioned as memorials and votive offerings or as grave markers, replacing the vast amphora (two-handled, narrow-necked jars used for wine and oils) and kraters (wide-mouthed vessels) of the previous periods, yet still typically painted in vivid colors.

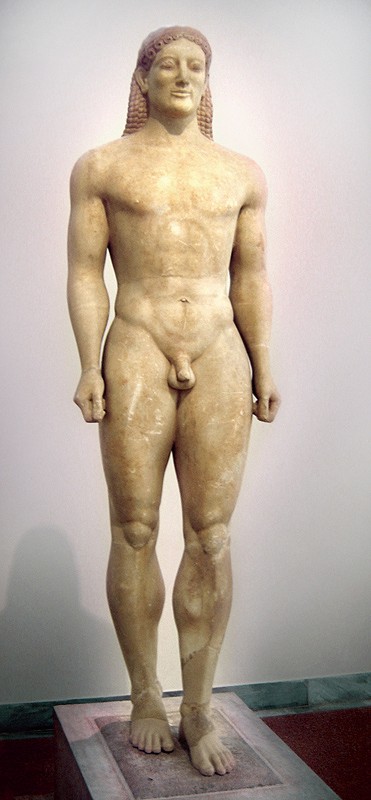

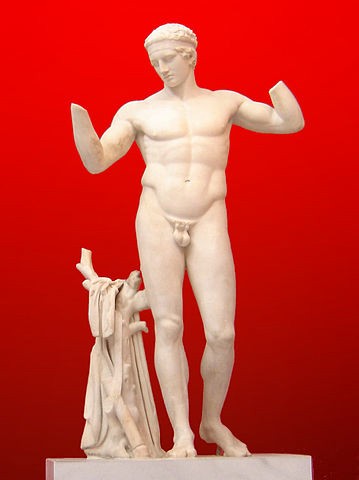

Kouroi

Kouroi statues (singular, kouros), depicting idealized, nude male youths, were first seen during this period. Carved in the round, often from marble, kouroi are thought to be associated with Apollo; many were found at his shrines and some even depict him. Emulating the statues of Egyptian pharaohs, the figure strides forward on flat feet, arms held stiffly at its side with fists clenched. However, there are some importance differences: kouroi are nude, mostly without identifying attributes and are free-standing.

Early kouroi figures share similarities with Geometric and Orientalizing sculpture, despite their larger scale. For instance, their hair is stylized and patterned, either held back with a headband or under a cap. The New York Kouros strikes a rigid stance and his facial features are blank and expressionless. The body is slightly rounded and the musculature is indicated by incised lines.

As kouroi figures developed, they began to lose their Egyptian rigidity and became increasingly naturalistic. The kouros figure of Kroisos, an Athenian youth killed in battle, still depicts a young man with an idealized body. This time though, the body’s form shows realistic modeling.

The muscles of the legs, abdomen, chest and arms appear to actually exist and seem to function and work together. Kroisos’s hair, while still stylized, falls naturally over his neck and onto his back, unlike that of the New York Kouros, which falls down stiffly and in a single sheet. The reddish appearance of his hair reminds the viewer that these sculptures were once painted.

Archaic Smile

Kroisos’s face also appears more naturalistic when compared to the earlier New York Kouros. His cheeks are round and his chin bulbous; however, his smile seems out of place. This is typical of this period and is known as the Archaic smile. It appears to have been added to infuse the sculpture with a sense of being alive, and possibly to give an added quality of realism.

Kore

A kore (plural korai) sculpture depicts a female youth. Unlike the kouroi – athletic, nude young men – the female korai are fully-clothed, in the idealized image of decorous women. Male bodies were perceived as public, belonging to the state, while women’s bodies were deemed private and belonged to their fathers (if unmarried) or husbands.

However, they also have Archaic smiles, with arms either at their sides or extended, holding an offering. The figures are stiff and retain more block-like characteristics than their male counterparts. Their hair is also stylized, depicted in long strands or braids that cascade down the back or over the shoulder.

The Peplos Kore (c. 530 BCE) depicts a young woman wearing a peplos, a heavy wool garment that drapes over the whole body, obscuring most of it. A slight indentation between the legs, a division between her torso and legs, and the protrusion of her breasts merely hint at the form of the body underneath.

Remnants of paint on her dress tell us that it was painted yellow with details in blue and red that may have included images of animals. The presence of animals on her dress may indicate that she is the image of a goddess, perhaps Artemis, but she may also just be a nameless maiden.

Later korai figures also show stylistic development, although the bodies are still overshadowed by their clothing. The example of a Kore (520–510 BCE) from the Athenian Acropolis shows a bit more shape in the body such as defined hips instead of a dramatic belted waistline, although the primary focus of the kore is on the clothing and the drapery. This kore figure wears a chiton (a woolen tunic), a himation (a lightweight undergarment), and a mantle (a cloak). Her facial features are still generic and blank, and she has an Archaic smile. Even with the finer clothes and additional adornments such as jewelry, the figure depicts the idealized Greek female, fully clothed and demure.

Ceramics in the Greek Archaic Period

Archaic black- and red-figure painting began to depict more naturalistic bodies by conveying form and movement.

Key Points

- Black-figure painting was used throughout the Archaic period before diminishing under the popularity of red-figure painting.

- Exekias is considered one of the most talented and influential black-figure painters due to his ability to convey emotion, use intricate lines, and create scenes that trusted the viewer to comprehend the scene.

- Red-figure painting was developed in 530 BCE by the Andokides Painter, a style that allows for more naturalism in the body due to the use of a brush.

- The first red-figure paintings were produced on bilingual vases, depicting one scene on each side, one in black figure and the other in red figure.

- The painters Euthyides and Euphronios were two of the most talented Archaic red-figure painters, with their vessels depict space, movement, and naturalism.

Key Terms

- burin: A chisel with a sharp point, used for engraving; an engraver.

- slip: A thin, slippery mix of clay and water.

- red-figure: One of the most important styles of figural Greek vase painting, based on the figural depictions in red color on a black background.

- black-figure: A style of Greek vase painting that is distinguished by silhouette-like figures on a red background.

Pottery Decoration Overview

The Archaic period saw a shift in styles of pottery decoration, from the repeating patterns of the Geometric period, through the Eastern-influenced Orientalizing style, to the more naturalistic black- and red-figure techniques. During this time, figures became more dynamic and defined by more organic—as opposed to geometric—elements.

Black-Figure Painting

Black-figure painting, which derives its name from the black figures painted on red backgrounds, was developed by the Corinthians in the seventh century BCE and became popular throughout the Greek world during the Archaic period. As painters became more confident working in the medium, human figures began to appear on vases and painters and potters began signing their creations.

Exekias

Exekias, considered the most prominent black-figure painter of his time, worked between 545 and 530 BCE in Athens. He is regarded by art historians as an artistic visionary whose masterful use of incision and psychologically sensitive compositions mark him as one of the greatest of all Attic vase painters. His vessels display attention to detail and precise, intricate lines.

Exekias is also well-known for reinterpreting mythologies. Instead of providing the entire story, as Kleitias did on the François Vase, he paints single scenes and relies on the viewer to interpret and understand the narrative.

One example is an amphora that depicts the Greek warriors Achilles and Ajax playing dice. Both men are decorated with fine incised details, showing elaborate textile patterns and almost every hair in place. As they wait for the next battle with the Trojans, their game foreshadows their fates. Inscribed text allows the two figures to speak: “Achilles has rolled a four, while Ajax rolled a three.” Both men will die during the the Trojan War, but Achilles dies a hero while Ajax is consistently considered second best, eventually committing suicide.

Architecture of the Classical Period

Mathematical Scale

All temples, however, were built on a mathematical scale and every aspect of them is related to one another through ratios. For instance, most Greek temples (except the earliest) followed the equation 2x + 1 = y when determining the number of columns used in the peripteral colonnade.

In this equation, x stands for the number of columns across the front, the shorter end, while y designates the columns down the sides. The number of columns used along the length of the temple was twice the number plus one the number of columns across the front. Due to these mathematical ratios, we are able to accurately reconstruct temples from small fragments.

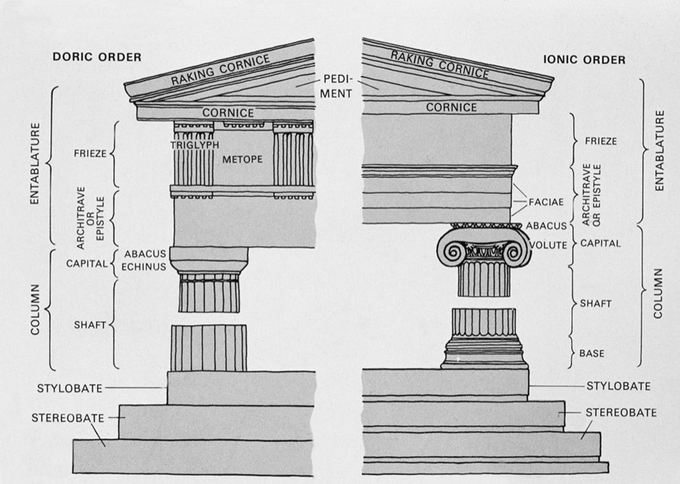

Doric Order

The style of Greek temples is divided into three different and distinct orders, the earliest of which is the Doric order. These temples had columns that rested directly on the stylobate without a base. Their shafts were fluted with twenty parallel grooves that tapered to a sharp point.

The capitals of Doric columns had a simple, unadorned square abacus and a flared echinus that was often short and squashed. Doric columns are also noted for the presence of entasis, or bulges in the middle of the column shaft. This was perhaps a way to create an optical illusion or to emphasize the weight of the entablature above, held up by the columns.

The Doric entablature was also unique to this style of temples. The frieze was decorated with alternating panels of triglyphs and metopes. The triglyphs were decorative panels with three grooves or glyphs that gave the panel its name. The stone triglyphs mimicked the head of wooden beams used in earlier temples. Between the triglyphs were the metopes.

Decorative Spaces

Sculptors used the metope spaces to depict mythological occurrences, often with historical or cultural links to the site on which the temple stood.

The Early Classical Period

Marble Sculpture and Architecture

Early Classical Greek marble sculptures and temple decorations display new conventions to depict the body and severe style facial expressions.

Key Points

- The sculpture found on the pediment and metopes at the Temple of Zeus at Olympia represent the style of relief and pedimental sculptural during the Early Classical period.

- The Severe style is an Early Classical style of sculpting where the body is depicted naturalistically and the face remains blank and expressionless. This style notes the artist’s understanding of the body’s musculature, while maintaining a screen between art and reality with the stoic face.

- Contrapposto is a weight shift depicted in the body that rotates the waist, hips, chest, shoulders, and sometimes even the neck and head of the figure. It increases that naturalism in the body since it correctly mimics the inner workings of human musculature.

- Kritios Boy is an early example of contrapposto and Severe style. This marble statue depicts a nude male youth, muscular and well built, with an air of naturalism that dissolves when examining his Severe style face.

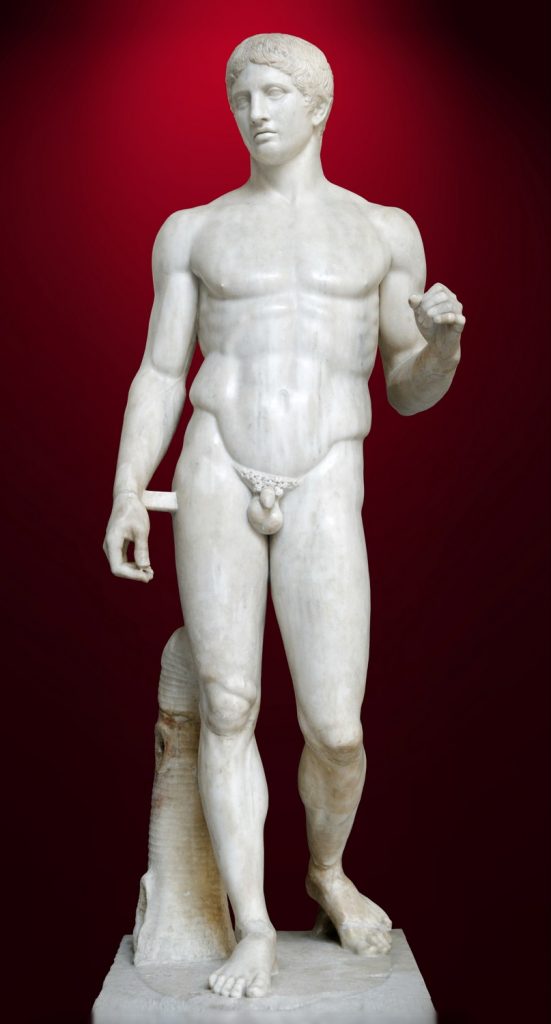

- Polykleitos, an artist and art theorist, developed a canon for the creation of the perfect male body based on mathematical proportions. His Doryphoros (Spear Bearer) is believed to be a sculptural representation of his treatise. The figure stands in contrapposto, with a Severe-style face.

Key Terms

- Severe style: The dominant idiom of Greek sculpture in the period from 490 to 450 BCE. It marks the breakdown of the canonical forms of Archaic art and the transition to the greatly expanded vocabulary and expression of the classical movement of the late 5th century.

- Perserchutt: A German term meaning Persian debris or rubble, that refers to the location of ritually buried architectural and votive sculptures that were destroyed following the sack of Athens by the Persians. The area was first excavated by the Germans in the late 19th century.

- hexastyle: Describes a building with six columns in the front and back and 13 down each side.

Kritios Boy

A slightly smaller-than-life-sized sculpture known as the Kritios Boy was dedicated to Athena by an athlete and found in the rubble of the Athenian Acropolis. Its title derives from a famous artist to whom the sculpture was once attributed.

The marble statue is a prime example of the Early Classical sculptural style and demonstrates the shift away from the stiff style seen in Archaic kouroi. The torso suggests an understanding of the body and the plasticity of the muscles and skin that allows the statue to appear life-like. Part of this illusion is created by a stance known as contrapposto. This describes a person with his or her weight shifted onto one leg, which initiates a shift in the hips, chest, and shoulders and gives a stance that is more dramatic and naturalistic than a stiff, frontal pose. This contrapposto position animates the figure through the relationship of tense and relaxed limbs.

However, the face of the Kritios Boy is expressionless, which contradicts the naturalism seen in his body. This is known as the Severe style. The blank expression causes the sculpture to appear less naturalistic, which creates a psychological remove between the art and the viewer. This differs from the use of the Archaic smile (now gone), which was added to sculpture to increase the naturalism. Contradicting the emotionless expression would have been the eyes which originally held inlaid stone to give the sculpture a more lifelike appearance.

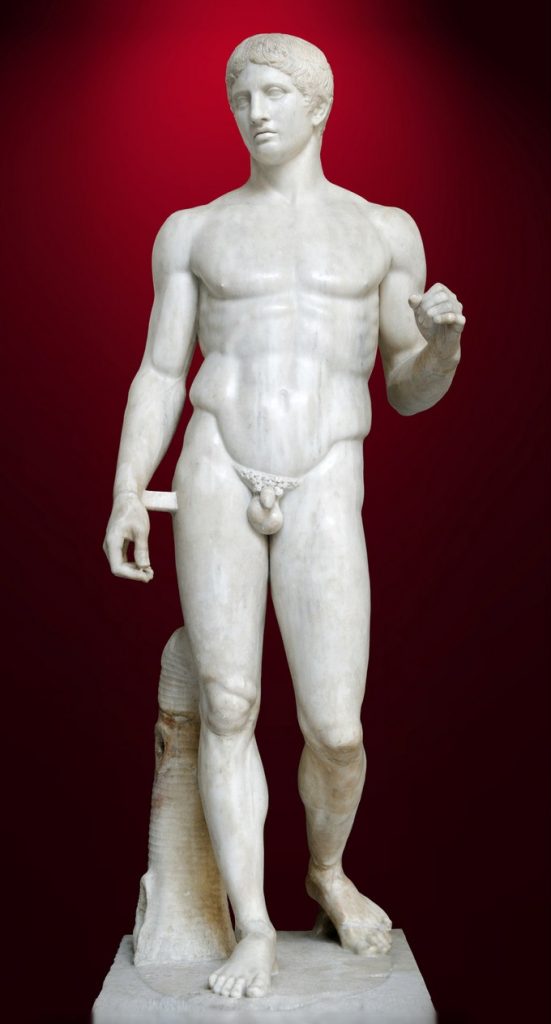

Polykleitos

Polykleitos was a well-known Greek sculptor and art theorist during the early- to mid-fifth century BCE. He is most renowned for his treatise on the male nude, known as the Canon, which describes the ideal, aesthetic body based on mathematical proportions and Classical conventions such as contrapposto.

His Doryphoros, or Spear Bearer, is believed to be his representation of the Canon in sculpted form. The statue depicts a young, well-built soldier holding a spear in his left hand with a shield attached to his left wrist. Both military implements are now lost. The figure has a Severe-style face and a contrapposto stance. In another development away from the stiff and seemingly immobile Archaic style, the Doryphoros’ left heel is raised off the ground, implying an ability to walk.

This sculpture demonstrates how the use of contrapposto creates an S-shaped composition. The juxtaposition of a tension leg and tense arm and relaxed leg and relaxed arm, both across the body from each other, creates an S through the body. The dynamic power of this composition shape places elements—in this case the figure’s limbs—in opposition to each other and emphasizes the tension this creates. The statue, as a visualization of Polykleitos’ canon, also depicts the Greek sense of symmetria, the harmony of parts, seen here in the body’s proportions.

Bronze Sculpture in the Greek Early Classical Period

Surviving Greek bronze sculptures from the Early Classical period showcase the skill of Greek artists in representing the body and expressing motion.

Key Points

- While bronze was a popular material for Greek sculptors, few Greek bronzes exist today. We know a majority of famous sculptors and sculptures only through marble Roman copies and the few bronzes that survived, often from shipwrecks.

- Early Classical bronzes are sculpted in the lost wax method of casting. The figures are created in the Severe style with naturalistic bodies and blank, expressionless faces. The sculptures’ lightweight appearance is due to their hollowness and contributes to their implied potential energy and movement.

- The Charioteer of Delphi, the Riace Warriors, and the Artemision Bronze all display the sculpting characteristics of the Early Classical Severe style while also demonstrating the characteristics of bronze sculpting, including the lightness of the material and liveliness that could be achieved.

Key Terms

- strut: A support rod.

- contrapposto: The position of a figure whose hips and legs are twisted away from the direction of the head and shoulders.

- lost wax: A method of casting in which a model of the sculpture is made from wax. The model is used to make a mold. When the mold has set, the wax is made to melt and is poured away, leaving the mold ready to be used to cast the sculpture.

Greek Bronze Sculpture

Bronze was a popular sculpting material for the Greeks. Composed of a metal alloy of copper and tin, it provides a strong and lightweight material for use in the ancient world, especially in the creation of weapons and art. The Greeks used bronze throughout their history.

Because bronze is a valuable material, throughout history bronze sculptures were melted down to forge weapons and ammunition or to create new sculptures. The Greek bronzes that we have today mainly survived because of shipwrecks, which kept the material from being reused, and the sculptures have since been recovered from the sea and restored.

The Greeks used bronze as a primary means of sculpting, but much of our knowledge of Greek sculpture comes from Roman copies. The Romans were very fond of Greek art and collecting marble replicas of them was a sign of status, wealth, and intelligence in the Roman world.

Roman copies worked in marble had a few differences from the original bronze. Struts, or supports, were added to help buttress the weight of the marble as well as the hanging limbs that did not need support when the statue was originally made in the lighter and hollow bronze. The struts appeared either as rectangular blocks that connect an arm to the torso or as tree stumps against the leg, which supports the weight of the sculpture, as in this Roman copy of the Diadoumenos Atenas.

Lost Wax Technique

The lost wax technique, which is also known by its French name, cire perdue, is the process that ancient Greeks used to create their bronze statues. The first step of the process involves creating a full-scale clay model of the intended work of art. This would be the core of the model.

Once completed, a mold is made of the clay core and an additional wax mold is also created. The wax mold is then be placed between the clay core and the clay mold, creating a pocket, and the wax is melted out of the mold, after which the gap is filled with bronze. Once cooled, the exterior clay mold and interior clay core is are carefully removed and the bronze statue is cleaned, polished, and finished.

The multiple pieces are welded together, imperfections smoothed, and any additional elements, such as inlaid eyes and eyelashes, are then added. Because the clay mold must be broken when removing the figure, the lost wax method can be used only for making one-of-a-kind sculptures.

Riace Warriors

The Riace Warriors are a set of two nude, bronze sculptures of male warriors that were recovered off the coast of Riace, Italy. They are a prime example of Early Classical sculpture and the transition between Archaic to Classical sculpting styles. The figures are nude, unlike the Charioteer. Their bodies are idealized and appear dynamic, with freed limbs, a contrapposto shift in weight, and turned heads that imply movement. The muscles are modeled with a high degree of plasticity, which the bronze material amplifies through natural reflections of light. Additional elements, such as copper for the lips and nipples, silver teeth, and eyes inlaid with glass and bone, were added to the figures to increase their naturalism. Both figures originally held a shield and spear, which are now lost. Warrior B wears a helmet, and it appears that Warrior A once wore a wreath around his head.

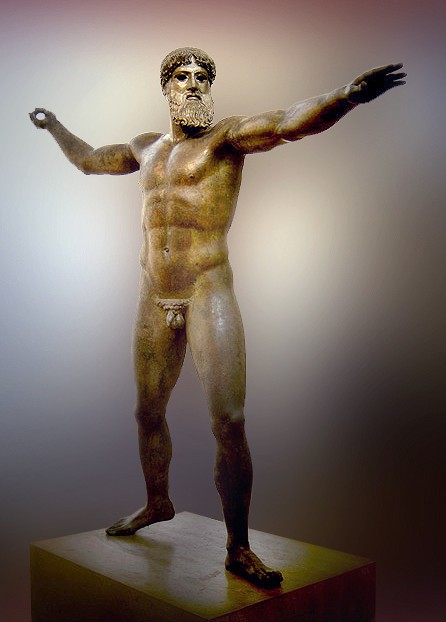

Artemision Bronze

The Artemision Bronze represents either Zeus or Poseidon. Both gods were represented with full beards to signify maturity. However, it is impossible to identify the sculpture as one god or the other because it can either be a lightning bolt (symbolic of Zeus) or a trident (symbolic of Poseidon) in his raised right hand.

The figure stands in heroic nude, as would be expected with a god, with his arms outstretched, preparing to strike. The bronze is in the Severe style with an idealized, muscular body and an expressionless face.

Like the Charioteer and the Riace Warriors, the Artemision Bronze once held inlaid glass or stone in its now-vacant eye sockets to heighten its lifelikeness. The right heel of the figure rises off the ground, which anticipates the motion the figure is about to undertake.

The full potential of the god’s motion and energy, as well as the grace of the body, is reflected in the modeling of the bronze.

The High Classical Period

Architecture in the Greek High Classical Period

High and Late Classical architecture is distinguished by its adherence to proportion, optical refinements, and its early exploration of monumentality.

Key Points

- Architecture during the Early and High Classical periods was refined and the optical illusions corrected to create the most aesthetically pleasing proportions. The High and Late Classical periods begin to tweak these principles and experiment with monumentality and space.

- Temples during the Late Classical period began to experiment with new architectural designs and decoration. The Tholos of Athena Pronaia at Delphi is a circular shrine with two rings of columns, the outer Doric and the inner Corinthian.

- The Temple of Epicurious at Bassae is noted for its unique ground plan and the use of architectural elements from all three Classical orders: Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian. The temple’s use of architectural decoration and a ground plan demonstrate changing aesthetics.

- The theater in the city of Epidauros is a prime example of advanced engineering skills during this period. The theater is built with refined acoustics that could amplify the sounds on the stage to every one of the theater’s 14,000 spectators.

Key Terms

- aniconic: Of, or pertaining to, representations without human or animal form.

- tholos: A circular structure, often a temple.

- peripteral: Surrounded by a single row of columns.

- prostyle: Free-standing columns across the front of a building.

- entablature: The area of a temple facade that lies horizontally atop the columns.

- elevation: A geometric projection of a building, or other object, on a plane perpendicular to the horizon.

- Geometric period: An era of abstract and stylized motifs in ancient Greek vase painting and sculpture. The period was centered in Athens and flourished from 900 to 700 BCE.

- Pericles: A prominent and influential Greek statesman, orator, and the general of Athens during the city’s Golden Age—specifically, the time between the Persian and Peloponnesian wars.

- capital: The topmost part of a column.

Classical Greek Architecture Overview

During the Classical period, Greek architecture underwent several significant changes. The columns became more slender, and the entablature lighter during this period. In the mid-fifth century BCE, the Corinthian column is believed to have made its debut. Gradually, the Corinthian order became more common as the Classical period came to a close, appearing in conjunction with older orders, such as the Doric. Additionally, architects began to examine proportion and the chromatic effects of Pentelic marble more closely. In the construction of theaters, architects perfected the effects of acoustics through the design and materials used in the seating area. The architectural refinements perfected during the Late Classical period opened the doors of experimentation with how architecture could define space, an aspect that became the forefront of Hellenistic architecture.

Temples

Throughout the Archaic period, the Greeks experimented with building in stone and slowly developed their concept of the ideal temple. It was decided that the ideal number of columns would be determined by a formula in which twice the number of columns across the front of the temple plus one was the number of columns down each side (2x + 1 = y).

Many temples during the Classical period followed this formula for their peripteral colonnade, although not all. Furthermore, many temples in the Classical period and beyond are noted for the curvature given to the stylobate of the temple that compensated for optical distortions.

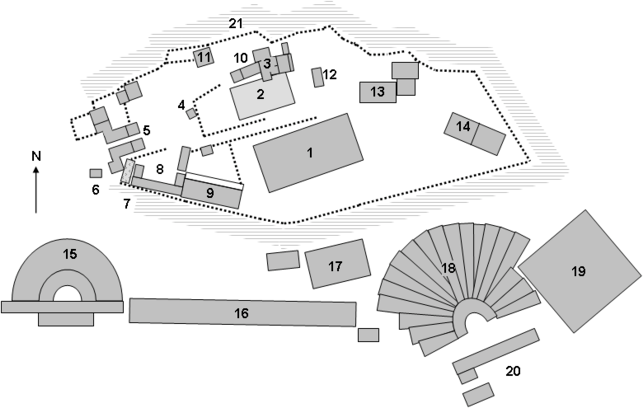

The Acropolis

The Athenian Acropolis is an ancient citadel in Athens containing the remains of several ancient buildings, including the Parthenon.

Key Points

- The Acropolis, dedicated to the goddess Athena, has played a significant role in the city from the time that the area was first inhabited during the Neolithic era. In recent centuries, its architecture has influenced the design of many public buildings in the Western hemisphere.

- Immediately following the Persian war in the mid-fifth century BCE, the Athenian general and statesman Pericles coordinated the construction of the site’s most important buildings including the Parthenon, the Propylaea, the Erechtheion, and the temple of Athena Nike.

- The structures on the Acropolis incorporated the Cyclopean foundations of older Mycenaean-era structures.

- In its heyday, the Parthenon featured a Doric facade and Ionic frieze interior, while the Doric Propylaea—the gateway to the Acropolis and an art gallery in the Classical era—lacked friezes and pedimental sculptures. The Ionic Erechtheion, believed to have been dedicated to the legendary King Erechtheus, features a porch supported by columnar caryatids. The Temple of Athena Nike, which celebrates Athenian war victories, was built in the Ionic order.

- The sculptures from each of these buildings depict scenes specific to their historical and mythological significance to Athens.

The Athenian Acropolis

The study of Classical-era architecture is dominated by the study of the construction of the Athenian Acropolis and the development of the Athenian agora. The Acropolis is an ancient citadel located on a high, rocky outcrop above and at the center of the city of Athens. It contains the remains of several ancient buildings of great architectural and historic significance.

The word acropolis comes from the Greek words ἄ (akron, meaning edge or extremity) and π (polis, meaning city). Although there are many other acropoleis in Greece, the significance of the Acropolis of Athens is such that it is commonly known as The Acropolis without qualification.

The Acropolis has played a significant role in the city from the time that the area was first inhabited during the Neolithic era. While there is evidence that the hill was inhabited as far back as the fourth millennium BCE, in the High Classical Period it was Pericles (c. 495–429 BCE) who coordinated the construction of the site’s most important buildings, including the Parthenon, the Propylaea, the Erechtheion, and the temple of Athena Nike.

The buildings on the Acropolis were constructed in the Doric and Ionic orders, with dramatic reliefs adorning many of their pediments, friezes, and metopes. In recent centuries, its architecture has influenced the design of many public buildings in the Western hemisphere.

Early History

Archaeological evidence shows that the acropolis was once home to a Mycenaean citadel. The citadel’s Cyclopean walls defended the Acropolis for centuries, and still remains today. The Acropolis was continually inhabited, even through the Greek Dark Ages when Mycenaean civilization fell.

It is during the Geometric period that the Acropolis shifted from being the home of a king to being a sanctuary site dedicated to the goddess Athena, whom the people of Athens considered their patron. The Archaic-era Acropolis saw the first stone temple dedicated to Athena, known as the Hekatompedon (Greek for hundred-footed).

This building was built from limestone around 570 to 550 BCE and was a hundred feet long. It has the original home of the olive-wood statue of Athena Polias, known as the Palladium, that was believed to have come from Troy.

In the early fifth century the Persians invaded Greece, and the city of Athens—along with the Acropolis—was destroyed, looted, and burnt to the ground in 480 BCE. Later the Athenians, before the final battle at Plataea, swore an oath that if they won the battle—that if Athena once more protected her city—then the Athenian citizens would leave the Acropolis as it is, destroyed, as a monument to the war. The Athenians did indeed win the war, and the Acropolis was left in ruins for thirty years.

Periclean Revival

It was immediately following the Persian war that the Athenian general and statesman Pericles funded an extensive building program on the Athenian Acropolis. Despite the vow to leave the Acropolis in a state of ruin, the site was rebuilt, incorporating all the remaining old materials into the spaces of the new site. The building program began in 447 BCE and was completed by 415 BCE. It employed the most famous architects and artists of the age and its sculpture and buildings were designed to complement and be in dialog with one another.

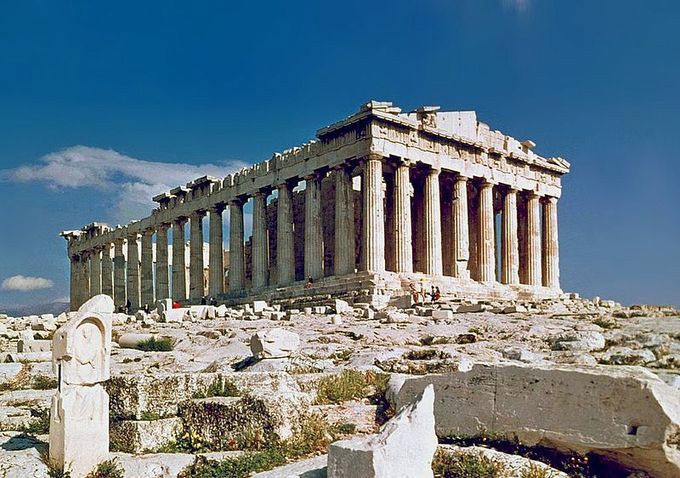

The Parthenon

The Parthenon represents a culmination of style in Greek temple architecture. The optical refinements found in the Parthenon—the slight curve given to the whole building and the ideal placement of the metopes and triglyphs over the column capitals —represent the Greek desire to achieve a perfect and harmonious design known as symmetria.

While the artist Phidias was in charge of the overall plan of the Acropolis, a sort of general contractor, the architects Iktinos and Kallikrates designed and oversaw the construction of the Parthenon (447–438 BCE), the temple dedicated to Athena. The Parthenon is built completely from Pentalic marble, although parts of its foundations are limestone from a pre-480 BCE temple that was never completed. The design of the Parthenon varies slightly from the basic temple ground plan. The temple is peripteral, and so is surrounded by a row of columns. In front of both the pronaos (porch) and opisthodomos is a single row of prostyle columns. The opisthodomos is large, accounting for the size of the treasury of the Delian League, which Pericles moved from Delos to the Parthenon, appropriating the funds in order to restore the Akropolis. The pronaos is so small it is almost non-existent. Inside the naos is a two-story row of columns around the interior, and set in front of the columns is the cult statue of Athena. It is the most important surviving building of Classical Greece.

The Parthenon’s elevation has been streamlined and shows a mix of Doric and Ionic elements. The exterior Doric columns are more slender and their capitals are rigid and cone-like. The entablature also appears smaller and less weighty then earlier Doric temples. The exterior of the temple has a Doric frieze consisting of metopes and triglyphs.

Inside the temple are Ionic columns and an Ionic frieze that wraps around the exterior of the interior building. The whole building curves slightly in the center to compensate for the human eye. The columns also are said to have an entasis, a slight swelling in the center to make them appear more solid and stable. If the building was built perfectly at right angles and with straight lines, the human eye would see the lines as bowed. In order for the Parthenon to appear straight to the eye, Iktinos and Kallikrates added curvature to the building that the eye would interpret as straight.

The sculpted reliefs on the Parthenon’s metopes are both decorative and symbolic, and relate stories of the Greeks against the others. Each side depicts a different set of battles.

- Over the entrance on the east side is a Gigantomachy, depicting the battle between the giants and the Olympian gods.

- The west side depicts an Amazonomachy, showing a battle between the Athenians and the Amazons.

- The north side depicts scenes of the Greek sack of Troy at the end of the Trojan War.

- The south side depicts a Centauromachy, or a battle with centaurs. The Centauromachy depicts the mythical battle between the Greek Lapiths and the Centaurs that occurred during a Lapith wedding.

These scenes are the most preserved of the metopes and demonstrate how Phidias mastered fitting episodic narrative into square spaces. Taken in total, they symbolize the Greeks’ pride in their victory over the Persians represented by the various “monstrous” or barbaric creatures in the metopes.

The interior Ionic processional frieze wraps around the exterior walls of the naos. While the frieze may depict a mythical or historical procession, many scholars believe that it depicts a Panatheniac procession.

The Panathenaic procession occurred yearly through the city, leading from the Dipylon Gate to the Acropolis and culminating in a ritual changing of the peplos, or garment, worn by the ancient olive-wood statue of Athena. The processional scene begins in the southwest corner and wraps around the building in both directions before culminating in the middle of the of the west wall.

It begins with images of horsemen preparing their mounts, followed by riders and chariots, Athenian youth with sacrificial animals, elders and maidens, then the gods before culminating at the central event. The central image depicts Athenian maidens with textiles, replacing the old peplos with a new one.

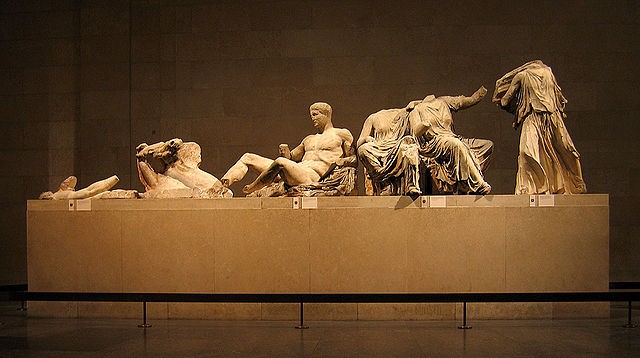

The east and west pediments depict scenes from the life of Athena and the east pediment is better preserved than the west; fortunately, both were described by ancient writers. The west pediment depicted the contest between Athena and Poseidon for the patronage of Athens. At the center of the pediment stood Athena and Poseidon, pulling away from each to create a strongly charged, dynamic, diagonal composition.

The east pediment depicted the birth of Athena. While the central image of Zeus, Athena, and Haphaestus has been lost, the surrounding gods, in various states of reaction, have survived.

Notice how the figures are all to the same scale and are arranged in a composition that allows them to fill the long, increasingly narrow space of the pediment. In addition, it is keeping with tradition up to this point in Greek art that the Goddesses are clothed while the male Gods are not. The drapery on the three Goddesses, however, is fluid and reveals the forms of the bodies underneath.

Upon entering the Acropolis from the Propylaea, or central gateway, visitors were greeted by a colossal bronze statue of Athena Promachos (c. 456 BCE), designed by Phidias. Accounts and a few coins minted with images of the statue allow us to conclude that the bronze statue portrayed a fearsome image of a helmeted Athena striding forward, with her shield at her side and her spear raised high, ready to strike.

The Temple of Athena Nike

One of the smaller but most elegant structures on the Acropolis is the Temple of Athena Nike (427–425 BCE), designed by Kallikrates in honor of the goddess of victory. It stands on the parapet of the Acropolis, to the southwest and to the right of the Propylaea. The temple is a small Ionic temple that consists of a single naos, where a cult statue stood fronted by four piers. The four piers aligned to the four Ionic prostyle columns of the pronaos. Both the pronaos and opisthodomos are very small, nearly non-existent, and are defined by their four prostyle columns.

The continuous frieze around the temple depicts battle scenes from Greek history. These representations include battles from the Persian and Peloponnesian Wars, including a cavalry scene from the Battle at Marathon and the Greek victory over the Persians at the Battle of Plataea.

The scenes on the Temple of Athena Nike are similar to the battle scenes on the Parthenon, which represented Greek dominance over non-Greeks and foreigners in mythical allegory. The scenes depicted on the frieze of the Temple of Athena Nike frieze display Greek and Athenian dominance and military power throughout historical events.

A parapet was added on the balustrade to protect visitors from falling down the steep hillside. Images of Nike, such as Nike Adjusting Her Sandal, are carved in relief. In this scene Nike is portrayed standing on one leg as she bends over a raised foot and knee to adjust her sandal. Her body is depicted in the new High Classical style.

Unlike Archaic sculpture, this scene actually depicts Nike’s body. Her body and muscles are clearly distinguished underneath her transparent yet heavy clothing.

This style, known as wet drapery, allows sculptors to depict the body of a woman while still preserving the modesty of the female figure. Although Nike’s body is visible, she remains fully clothed. This style is found elsewhere on the Acropolis, such as on the caryatids and, as noted above, on the women in the Parthenon’s pediment.

Sculpture in the Greek High Classical Period

High Classical sculpture demonstrates the shifting style in Greek sculptural work as figures became more dynamic and less static.

Key Points

- After mastering the portrayal of naturalistic bodies from stone, Greek sculptors began to experiment with new poses that expanded the repertoire of Greek art. The sculptures of this later period are moving away from the Classical characteristics they still maintain: idealism and the Severe style.

- Polykleitos is most well known for his Canon, depicted in the Doryphoros, but is also known for his Diadumenos and Discophoros. These two, sculpted athletes are also done in accordance to his canon and are depicted in contrapposto with chiastic poses.

- Phidias was one of the most renowned sculptors his time. He oversaw the sculptural program for the Athenian Acropolis and is also known for his giant chryselephantine cult statues of Zeus and Athena Parthenos.

- Myron is a bronze sculptor of the High Classical period. His statues are known for being imbued with potential energy. His Discobolos is poised to spring, preparing to throw a discus. While still idealized, the figure appears to be frozen in an action of intense movement.

Key Terms

- chryselephantine: Made of gold and ivory.

- aegis: An attribute of Zeus or Athena, usually represented as a goatskin shield.

Polykleitos

Polykleitos was a famous Greek sculptor who worked in bronze. He was also an art theorist who developed a canon of proportion (called the Canon) that is demonstrated in his statue of Doryphoros (Spear Bearer) Many of Polykleitos’s bronze statues from the Classical period, including the Doryphoros, survive only as Roman copies executed in marble. Polykleitos, along with Phidias, is thought to have created the style recognized as Classical Greek sculpture.

Another example of the Canon at work is seen in Polykleitos’s statue of Diadumenos, a youth trying on a headband, and his statue Discophoros, a discus bearer. Both Roman marble copies depict athletic, nude, male figures. The bodies of the two figures are idealized. The nudity allows the harmony of parts, or symmetria, to easily be seen and illustrates the principles discussed in the Canon. The Canon focused on the proportion of parts of the body in relationship to each other to create the ideal male form. Both statues demonstrate fine proportion, ideal balance, and the definable parts of the body.

Doryphoros is shown in the contrapposto stance. He shifts his weight to his right leg. The sculpture, demonstrates the flexibility of composition based on the Canon and the innate liveliness produced by contrapposto postures. Despite the lively aspects and unique pose of the figure, it still retain the Severe style and expressionless face of early Greek sculpture.

Polykleitos not only worked in bronze but is also known for his chryselephantine cult statue of Hera at Argos, which in ancient times was compared to Phidias’ colossal chryselephantine cult statues.

Phidias

Phidias was the sculptor and artistic director of the Athenian Acropolis and oversaw the sculptural program of all the Acropolis’ buildings. He was considered one of the greatest sculptors of his time and he created monumental cult statues of gold and ivory for city-states across Greece.

Phidias is well known for the Athena Parthenos, the colossal cult statue in the naos of the Parthenon. While the statue has been lost, written accounts and reproductions (miniatures and representations on coins and gems) provide us with an idea of how the sculpture appeared.

It was made out of ivory, silver, and gold and had a wooden core support. Athena stood crowned, wearing her helmet and aegis. Her shield stood upright at her left side and her left hand rested on it while in her right hand she held a statue of Nike. An artist’s reconstruction is housed in the Parthenon in Nashville.

Sculpture in the Hellenistic Period

A key component of Hellenistic sculpture is the expression of a sculpture’s face and body to elicit an emotional response from the viewer.

Key Points

- Hellenistic sculpture takes the naturalism of the body’s form and expression to level of hyper-realism where the expression of the sculpture’s face and body elicit an emotional response.

- Drama and pathos are new factors in Hellenistic sculpture. The style of the sculpting is no longer idealized. Rather, they are often exaggerated, and details are emphasized to add a new, heightened level of motion and pathos.

- New compositions and states of mind are explored in Hellenistic sculptures including old age, drunkenness, sleep, agony, and despair.

- Portraiture became popular in this period. The subjects are depicted with a sense of naturalism that displays their imperfections.

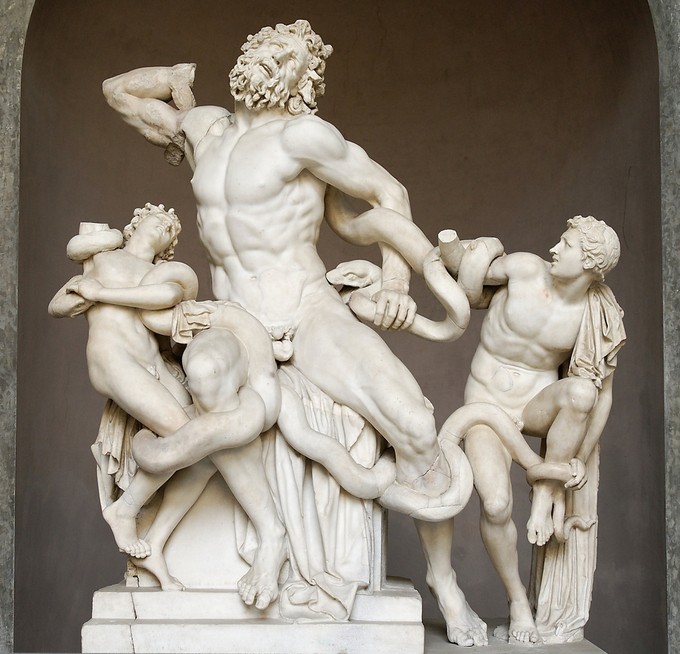

- Hellenistic sculpture was in especially high demand after the Greek peninsula fell to the Romans in 146 BCE. Notable sculptures produced for Roman patrons include Laocoön and His Sons and the Farnese Bull.

Key Terms

- satyr: A male companion of Pan or Dionysus with the tail of a horse and a perpetual erection. Also known as a faun.

- patrician: An aristocrat or other elite member of society; it may also be used as an adjective.

- pathos: That quality or property of anything that touches the feelings or excites emotions and passions, especially that which awakens tender emotions, such as pity, sorrow, and the like; a contagious warmth of feeling, action, or expression; a pathetic quality.

Hellenistic sculpture continues the trend of increasing naturalism seen in the stylistic development of Greek art. During this time, the rules of Classical art were pushed and abandoned in favor of new themes, genres, drama, and pathos that were never explored by previous Greek artists.

Furthermore, the Greek artists added a new level of naturalism to their figures by adding an elasticity to their form and expressions, both facial and physical. These figures interact with their audience in a new theatrical manner by eliciting an emotional reaction from their view—this is known as pathos.

Nike of Samothrace

One of the most iconic statues of the period, the Nike of Samothrace, also known as the Winged Victory (c. 190 BCE), commemorates a naval victory. This Parian marble statue depicts Nike, now armless and headless, alighting onto the prow of the ship. The prow is visible beneath her feet, and the scene is filled with theatricality and naturalism as the statue reacts to her surroundings.

Nike’s feet, legs, and body thrust forward in contradiction to her drapery and wings that stream backwards. Her clothing whips around her from the wind and her wings lift upwards. This depiction provides the impression that she has just landed and that this is the precise moment that she is settling onto the ship’s prow. In addition to the sculpting, the figure was most likely set within a fountain, creating a theatrical setting where both the imagery and the auditory effect of the fountain would create a striking image of action and triumph.

Venus de Milo

Also known as the Aphrodite of Melos (c. 130–100 BCE), this sculpture by Alexandros of Antioch, is another well-known icon of the Hellenistic period. Today the goddess’s arms are missing. It has been suggested that one arm clutched at her slipping drapery while the other arm held out an apple, an allusion to the Judgment of Paris and the abduction of Helen.

Originally, like all Greek sculptures, the statue would have been painted and adorned with metal jewelry, which is evident from the attachment holes. This image is in some ways similar to Praxitiles’ Late Classical sculpture Aphrodite of Knidos (fourth century BCE), but it is considered to be more erotic than its earlier counterpart.

For instance, while she is covered below the waist, Aphrodite makes little attempt to cover herself. She appears to be teasing and ignoring her viewer, instead of accosting him and making eye contact.

Altered States

While the Nike of Samothrace exudes a sense of drama and the Venus de Milo a new level of feminine sexuality, other Greek sculptors explored new states of being. Instead of reproducing images of the ideal Greek male or female, as was favored during the Classical period, sculptors began to depict images of the old, tired, sleeping, and drunk—none of which are ideal representations of a man or woman.

Drunken Old Woman

Images of drunkenness were also created of women, which can be seen in a statue attributed to the Hellenistic artist Myron of a drunken beggar woman. This woman sits on the floor with her arms and legs wrapped around a large jug and a hand gripping the jug’s neck.

Grape vines decorating the top of the jug make it clear that it holds wine. The woman’s face, instead of being expressionless, is turned upward and she appears to be calling out, possibly to passersby. Not only is she intoxicated, but she is old: deep wrinkles line her face, her eyes are sunken, and her bones stick out through her skin.

Roman Patronage

The Greek peninsula fell to Roman power in 146 BCE. Greece was a key province of the Roman Empire, and the Roman’s interest in Greek culture helped to circulate Greek art around the empire, especially in Italy, during the Hellenistic period and into the Imperial period of Roman hegemony.

Greek sculptors were in high demand throughout the remaining territories of the Alexander’s empire and then throughout the Roman Empire. Famous Greek statues were copied and replicated for wealthy Roman patricians and Greek artists were commissioned for large-scale sculptures in the Hellenistic style. Originally cast in bronze, many Greek sculptures that we have today survive only as marble Roman copies. Some of the most famous colossal marble groups were sculpted in the Hellenistic style for wealthy Roman patrons and for the imperial court. Despite their Roman audience, these were purposely created in the Greek style and continued to display the drama, tension, and pathos of Hellenistic art.

Laocoön and His Sons

Laocoön was a Trojan priest of Poseidon who warned the Trojans, “Beware of Greeks bearing gifts,” when the Greeks left a large wooden horse at the gates of Troy. Athena or Poseidon (depending on the story’s version), upset by his vain warning to his people, sent two sea serpents to torture and kill the priest and his two sons.

Laocoön and His Sons, a Hellenistic marble sculpture group (attributed by the Roman historian Pliny the Elder to the sculptors Agesander, Athenodoros, and Polydorus from the island of Rhodes) was created in the early first century CE to depict this scene from Virgil’s epic, The Aeneid.

Similar to other examples of Hellenistic sculpture, Laocoön and His Sons depicts a chiastic scene filled with drama, tension, and pathos. The figures writhe as they are caught in the coils of the serpents. The faces of the three men are filled with agony and toil, which is reflected in the tension and strain of their muscles. Laocoön stretches out in a long diagonal from his right arm to his left as he attempts to free himself.

His sons are also entangled by the serpents, and their faces react to their doom with confusion and despair. The carving and detail, the attention to the musculature of the body, and the deep drilling, seen in Laocoön’s hair and beard, are all characteristic elements of the Hellenistic style.