27 Golden Age of Dutch Painting

Rembrandt, Hals, Leyster

Hendrick ter Brugghen, Gerrit van Honthorst, Frans Hals, and Judith Leyster were important genre painters of the Dutch Republic. Rembrandt painted history paintings, portraits, genre paintings, landscape and is probably the most well-known of all painters of the Dutch Golden Age.

Key Points

- Ter Brugghen and Honthorst were both artists from the Dutch city of Utrecht who worked in the Caravaggisti tradition, emulating Caravaggio’s dramatic use of light and shadow. Both artists were directly inspired by their travels to Italy.

- Tavern scenes and other depictions of lively entertainment were common subjects for genre painters of this period.

- Frans Hals, another well-known Dutch painter, is remembered primarily for his portraiture and his pioneering use of loose brushwork.

- Judith Leyster is one of the few recognized female artists of the Dutch Golden Age and is known for depicting female subjects in domestic interior scenes.

- Leyster’s work is extremely similar to Hals, leading some historians to speculate that she may have been his apprentice.

- Rembrandt is known for his capturing of the “inner” person; he painted self-portraits throughout his life leaving a record of his development and interior life.

Key Terms

- chiaroscuro: An artistic technique developed during the Renaissance, referring to the use of exaggerated light contrasts in order to create the illusion of volume.

- Caravaggisti: Stylistic followers of the 16th century Italian Baroque painter Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio.

- Mannerism: A style of art developed at the end of the High Renaissance, characterized by the deliberate distortion and exaggeration of perspective, especially the elongation of figures.

The Dutch Golden Age

The Dutch Golden Age was a period in the history of Holland generally spanning the 17th century, during and after the later part of the Eighty Years’ War (1568–1648) for Dutch independence. Although Dutch painting of the Golden Age comes in the general European period of Baroque painting and often shows many of its characteristics, most lacks the idealization and love of splendor typical of much Baroque work, including that of neighboring Flanders . Most work in Holland during this era, including that for which the period is best known, reflects the traditions of detailed realism inherited from Early Netherlandish painting.

A distinctive feature of the period is the proliferation of distinct genres of paintings, with the majority of artists producing the bulk of their work within one of these. The full development of this specialization is seen from the late 1620s, and the period from then until the French invasion of 1672 is the core of Golden Age painting. The Utrecht Caravaggisti Hendrick ter Brugghen and Gerrit van Honthorst, as well as Frans Hals and Judith Leyster, were genre painters of the Dutch Republic. Their work generally depicted taverns and other scenes of entertainment (Merry Company paintings) hat catered to the tastes and interests of a growing segment of the Dutch middle class.

Ter Brugghen’s favorite subjects were half-length figures of drinkers or musicians, but he also produced larger-scale religious images and group portraits. He carried with him Caravaggio’s influence, and his paintings have a strong dramatic use of light and shadow, as well as emotionally charged subjects. Though he died fairly young at age 41, his work was well received and highly influential in his lifetime.

Gerard van Honthorst (1590—1656) was born in Utrecht and also studied under Abraham Bloemaert. In 1616, Honthorst also traveled to Italy and was deeply influenced by the recent art he encountered there. Honthorst returned to Utrecht in 1620 and went on to build a considerable reputation, both in the Dutch Republic and abroad.

Honthorst briefly became a court painter to Charles I in England in 1628. His popularity in the Netherlands was such that he opened a second studio in The Hague, where he painted portraits of members of the court and taught drawing. Honthorst cultivated the style of Caravaggio and had great skill at chiaroscuro , often painting scenes illuminated by a single candle. Apart from portraiture, he is known for painting tavern scenes with musicians, gamblers, and people eating.

Hals

Frans Hals the Elder (c. 1582—1666) was most notable for his loose painterly brushwork, a lively style he helped introduce into Dutch art. Hals was also instrumental in the evolution of 17th century group portraiture. He is perhaps best known for his portraits, which were primarily of wealthy citizens and prominent merchants like Pieter van den Broecke and Isaac Massa. He also painted large group portraits for local civic guards and the regents of local hospitals. His pictures illustrate the various strata of society: banquets or meetings of officers, guildsmen, local councilmen from mayors to clerks, itinerant players and singers, gentlefolk, fishwives, and tavern heroes. In his group portraits, such as the The Officers of the St Adrian Militia Company, Hals captures each character in a different manner. Hals was fond of daylight and silvery sheen, in contrast to Rembrandt’s use of golden glow effects.

Judith Leyster

Judith Jans Leyster (1609—1660) was one of three significant women artists in Dutch Golden Age painting. The other two, Rachel Ruysch and Maria van Oosterwijk, were specialized painters of flower still lifes, while Leyster painted genre works, a few portraits, and a single still life. Leyster largely gave up painting after her marriage, which produced five children. Leyster was particularly innovative in her domestic genre scenes. In them, she creates quiet scenes of women at home, which were not a popular theme in Holland until the 1650s.

Although well-known during her lifetime and esteemed by her contemporaries, Leyster and her work were largely forgotten after her death. Leyster was rediscovered in 1893 when the Louvre purchased what it thought was a Frans Hals painting, only to find it had, in fact, been painted by Judith Leyster. Some historians have asserted that Hals may have been Leyster’s teacher due to the close similarity between their work; for example, Leyster’s The Merry Drinker from 1629 has a very strong resemblance to The Jolly Drinker of 1627—28 by Hals.

These types of paintings, of people engaged in drinking, music, or gambling, were called “Merry Company” paintings and were meant to bring to mind the parable of the Prodigal Son who squandered his inheritance on wine, women, and song.

Rembrandt

Rembrandt is remembered as one of the greatest artists in European history and the most important in the Dutch Golden Age.

Key Points

- Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (1606—1669) is primarily known for portraits of his contemporaries, self-portraits, landscapes, and illustrations of scenes from the Bible.

- Rembrandt’s self-portraits are exceptionally sincere, revealing, and personal, illustrating his development over time.

- Stylistically, Rembrandt’s work evolved from smooth to rough over the course of his lifetime.

- The thick, coarse strokes in Rembrandt’s work were unconventional at the time and poorly received by many of his contemporaries, though this technique is now viewed as essential to the emotional resonance of his work.

- Though he is remembered as the master of Dutch painting, Rembrandt’s success was uneven during his lifetime.

Key Terms

- variegated: Streaked, spotted, or otherwise marked with a variety of color; very colorful.

- Caravaggisti: Stylistic followers of the 16th century Italian Baroque painter Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio.

- chiaroscuro: An artistic technique popularized during the Renaissance, referring to the use of exaggerated light contrasts in order to create the illusion of volume.

Overview: Rembrandt

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (1606—1669) was a Dutch painter and etcher during the Dutch Golden Age, a period of great wealth and cultural achievement. Though Rembrandt’s later years were marked by personal tragedy and financial hardship, his etchings and paintings were popular throughout his lifetime, earning him an excellent reputation as an artist and teacher. In 1626, Rembrandt produced his first etchings, the wide dissemination of which would largely account for his international fame.

Characteristics of Rembrandt’s Work

Among the more prominent characteristics of Rembrandt’s work is his use of chiaroscuro , the theatrical employment of light and shadow. This technique was most likely derived from the Dutch Caravaggisti, followers of the Italian Baroque painter Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio who had first used the chiaroscuro technique. Also notable are his dramatic and lively presentation of subjects, devoid of the rigid formality that his contemporaries often displayed, and a visible compassion for the human subject, irrespective of wealth and age.

Throughout his career, Rembrandt took as his primary subjects the themes of portraiture (dependent upon commissions from wealthy patrons for survival), landscape, and narrative painting. For the last, he was especially praised by his contemporaries, who extolled him as a masterly interpreter of biblical stories for his skill in representing emotions and attention to detail. His immediate family often figured prominently in his paintings, many of which had mythical, biblical, or historical themes.

In later years, biblical themes were still often depicted, but his emphasis shifted from dramatic group scenes to intimate portrait-like figures (such as in James the Apostle, 1661). In his last years, Rembrandt painted his most deeply reflective self-portraits (he painted 15 from 1652 to 1669) and several moving images of both men and women (such as The Jewish Bride, c. 1666) in love, in life, and before God.

A popular genre, the civic portrait was also one in which Rembrandt made a number of important works. In The Sortie of Captain Banning Cocq’s Company of the Civic Guard (The Night Watch), he captures an active scene with a militia heading out into the daylight (the darkness of the canvas gave rise to the misnomer of “Night” watch until it was cleaned) unlike the traditional civic portrait composition of figures seated statically around a table. Each of the figures would have paid to be included except the drummer who was hired. Rembrandt added a few figures to enliven the scene and a few were lost when the painting was moved and cut down to fit a new space.

Stylistically, Rembrandt’s paintings progressed from the early “smooth” manner, characterized by fine technique in the portrayal of illusionistic form, to the late “rough” treatment of richly variegated paint surfaces, which allowed for an illusionism of form suggested by the tactile quality of the paint itself. Contemporary accounts sometimes remark disapprovingly of the coarseness of Rembrandt’s brushwork, and the artist himself was said to have dissuaded visitors from looking too closely at his paintings. The richly varied handling of paint, deeply layered and often apparently haphazard, suggests form and space in both an illusory and highly individual manner.

Self-Portraiture

Rembrandt’s self-portraits trace the progress from an uncertain young man, through the dapper and very successful portrait painter of the 1630s, to the troubled but massively powerful portraits of his old age. Together, they give a remarkably clear picture of the man, his appearance, and his psychological make-up, as revealed by his richly weathered face. In his portraits and self- portraits, he angles the sitter’s face in such a way that the ridge of the nose nearly always forms the line of demarcation between brightly illuminated and shadowy areas.

Landscape Art and Interior Painting

Landscape and interior genre painting of the Dutch Republic became increasingly sophisticated and realistic in the 17th century.

Key Points

- The ” classical phase” of Dutch landscapes began in the 1650s and retained an atmospheric quality; however, they featured contrasting light and color and the frequent presence of a compositional anchor, such as a prominent tree, tower, or ship.

- Paintings featuring animals emerged as a distinctive sub-genre of Dutch landscape painting around this time.

- Interior genre paintings were also extremely popular during the Dutch Republic, featuring lively scenes from everyday life, such as markets, inns, taverns, and street scenes, as well as domestic interiors.

- Jan Vermeer, whose work uniquely captured lighting in interior spaces, is now the most renowned genre painter of the Dutch Republic.

Key Terms

- atmospheric: Evoking a particular emotional or aesthetic quality.

- atmospheric perspective: A technique in which an illusion of depth is created by painting more distant objects with less clarity and with a lighter tone.

- genre: A stylistic category, especially of literature or other artworks.

Background: Dutch and Flemish Painting

Landscape painting was a major genre in the 17th century Dutch Republic that was inspired by Flemish landscapes of the 16th century, particularly from Antwerp. These Flemish works had not been particularly realistic, most having been painted in the studio, partly from imagination, and often still using the semi-aerial view style typical of earlier Netherlandish landscape painting, in the tradition of Joachim Patinir, Herri met de Bles, and Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

Dutch Landscapes

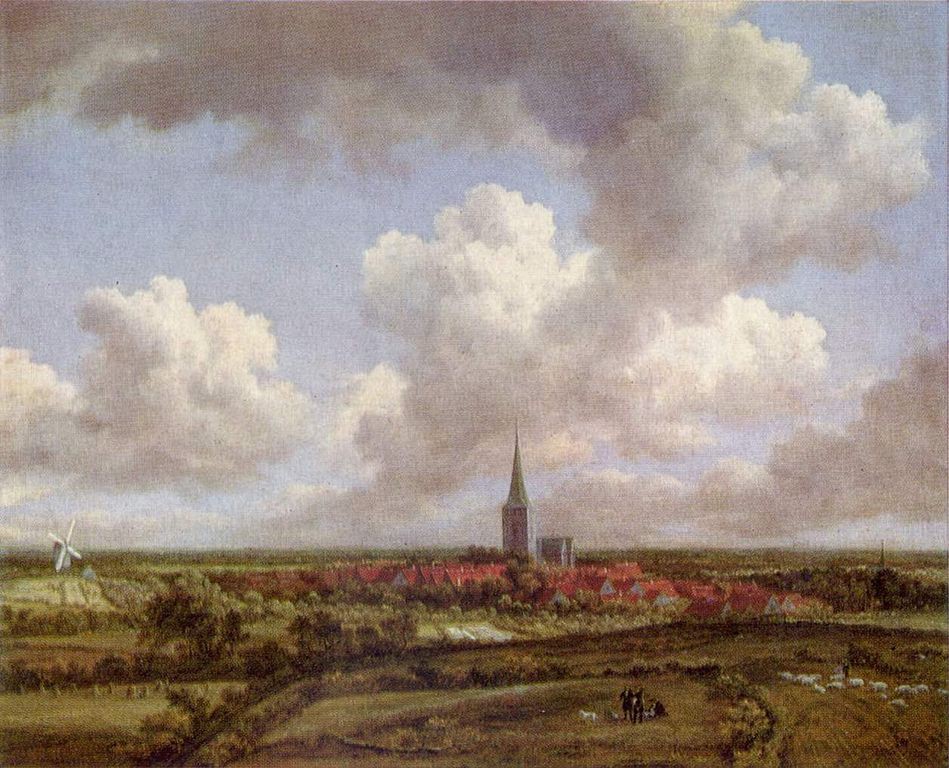

A more realistic style soon developed in the Netherlands, with lower horizons making it possible to emphasize the often impressive cloud formations so typical of the region. Favorite subjects were the dunes along the western sea coast and rivers with their broad adjoining meadows where cattle grazed, often with the silhouette of a city in the distance. Winter landscapes featured frozen canals and creeks. The sea was a favorite subject as well, holding both military and trade significance. Most Dutch painting carried with it a moralistic overtone; interior scenes were meant to bring to mind the bounty God had given the Dutch people and by taking care of it they were enacting almost a kind of religious worship. The land, much of which was reclaimed from the sea, also suggested the power and goodness of God.

The Classical Phase

From the 1650s, the “classical phase” began, retaining the atmospheric quality but with more expressive compositions and stronger contrasts of light and color. Compositions are often anchored by a single “heroic tree,” windmill, tower, or ship in marine works. The leading artist of this phase was Jacob van Ruisdael (1628–1682), who produced a great quantity and variety of work, including Nordic landscapes of dark and dramatic mountain pine forests with rushing torrents and waterfalls.

Dutch Interior Genre Painting

Apart from landscape painting, the development and enormous popularity of genre painting is the most distinctive feature of Dutch painting during this period. These genre paintings represented scenes or events from everyday life, such as markets, domestic interiors, parties, inn scenes, and street scenes.

Genre painting developed from the realism and detailed background activity of Early Netherlandish painting, which Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel the Elder were among the first to turn into their principal subjects. The style reflected the increasing prosperity of Dutch society, and settings grew steadily more comfortable, opulent, and carefully depicted as the century progressed.

Adriaen Brouwer is acknowledged as the Flemish master of peasant tavern scenes. Before Brouwer, peasants were typically depicted outdoors; he usually shows them in a plain and dim interior. Other artists whose common subjects were intimate interior scenes included Nicolaes Maes, Gerard ter Borch, and Pieter de Hooch. Jan Vermeer specialized in domestic interior scenes of middle class life; though he was long a very obscure figure, he is now the most highly regarded genre painter of Dutch history.

Johannes Vermeer used complex layers of paint to achieve the pearly light that envelopes his subjects. His forced perspective is sometimes attributed to the use of a camera obscura, but it is the quality of the light in his paintings that creates the quietness and timeless atmosphere he achieves.

Still Life Painting

Still life painting flourished during the Golden Age of the Dutch Republic.

Key Points

- Still lifes presented opportunities for painters to demonstrate their abilities in working with difficult textures and complex forms.

- The vanitas theme, a moral message frequently found in still life painting, alluded to the fleeting nature of life.

- Still lifes were frequently drawn by copying flowers in books, as the Dutch were leaders in scientific and botanical drawings and illustrations.

Key Terms

- vanitas: A type of still life painting, symbolic of mortality and characteristic of Dutch painting in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Overview: Dutch Still Life Painting

Early still lifes were relatively brightly lit, with bouquets of flowers arranged in a simple way. From the mid-15th century, arrangements that could fairly be called Baroque, usually against a dark background, became more popular. Painters from Leiden, The Hague, and Amsterdam particularly excelled in the genre . In addition to still life paintings, the Dutch led the world in botanical and other scientific drawings, prints, and book illustrations at this time.

The secular nature of Dutch Baroque painting made it arguably more available to be practiced by women painters than subjects requiring human anatomy or grand themes, both of which were considered to be inappropriate for women for much of art history. Judith Leyster, Maria van Oosterwijk, Maria Sybille Merian, and notably Rachel Ruysch are some of the most well-known artists of the period. Merian was German-born, but spent much of her life and died in Amsterdam. She traveled widely and published books of drawings and painting of the animals, insects, and plants in Dutch Suriname and South America. Considered to be one of the first and most important entemologists, her scientific work at the time was largely ignored. Rachel Ruysch (1664-1750) was noted for her still life of flowers, a popular subject at the time, but her work is considered to be the greatest of the late Baroque period in Amsterdam.

Themes of Still Lifes

Still lifes offered a great opportunity to display skill in painting textures and surfaces in great detail, and with highly realistic light effects. Food of all textures, colors, and shapes—silver cutlery, intricate patterns, and subtle folds in table cloths and flowers—all challenged painters.

Flower paintings were a popular sub-genre of still life and were favored by prominent women artists, such as Maria van Oosterwyck and Rachel Ruysch. Dead game, as well as birds painted live but studied from death, were another sub-genre, as were dead fish, a staple of the Dutch diet. Abraham van Beijeren painted this subject frequently.

Virtually all still lifes had a moralistic message, usually concerning the brevity of life. This is known as the vanitas theme. The vanitas theme was included in explicit symbols, such as a skull, or less obvious symbols such as a half-peeled lemon (representing life: sweet in appearance but bitter to taste). Flowers wilt and food decays, and silver is of no use to the soul. Nevertheless, the force of this message seems less powerful in the more elaborate pieces of the second half of the century.