15 Ancient Aegean

Sculpture of the Cyclades

Cycladic art during the Greek Bronze Age is noted for its abstract, geometric designs of male and female figures.

- The Cyclades are a chain of Greek islands in the middle of the Aegean Sea. They encircle the island of Delos.

- Cycladic marble figurines of abstract male and female forms have been found at burial sites. These figurines are small, abstract, and rely on geometric shapes and flat plans for their design and would have been painted.

- The female figurines depict a woman with her legs together and arms folded over her abdomen, with her breasts and pubic region emphasized.

- The male figures are often depicted sitting in a chair and playing a harp or a lyre.

- incised: To mark or cut the surface of an object for decoration.

- Cycladic: Of, or relating to the Cyclades.

- schematic: following a repeated geometric form and/or proportion.

The Cyclades were known for their white marble, mined during the Greek Bronze Age and throughout Classical history. Their geographical location placed them, like the island of Crete, in the center of trade between Greece, Egypt, Asia Minor, and the Near East. The indigenous civilization on the Cyclades reached its high point during the Bronze Age. The islands were later occupied by the Minoans, Mycenaeans, and later the Greeks.

Cycladic Sculptures

Cycladic art is best known for its small-scale, marble figurines. From the late fourth millennium BCE to the early second millennium BCE, Cycladic sculptures went through a series of stylistic shifts, with their bodily forms varying from geometric to organic. The purpose of these figurines is unknown, although all that have been discovered were located in graves. While it is clear that they were regularly used in funerary practices, their precise function remains a mystery.

Some are found in graves completly intact, others are found broken into pieces, others show signs of being used during the lifetime of the deceased, but some graves do not contain the figurines. Furthermore, the figurines were buried equally between men and women. The male and female forms do not seem to be identified with a specific gender during burial. These figures are based in simple geometric shapes. The repetition of geometric forms and proportions – like those of Egyptian figures – allow the term schematic to be applied to these figures.

Cycladic Female Figures

The abstract female figures all follow the same mold. Each is a carved statuette of a nude woman with her arms crossed over her abdomen. The bodies are roughly triangular and the feet are kept together. The head of the women is an inverted triangle with a rounded chin and the nose of the figurine protrudes from the center.

Each figure has modeled breasts, and incised lines draw attention to the pubic region with a triangle. The swollen bellies on some figurines might indicate pregnancy or symbolic fertility. The incised lines also provide small details, such as toes on the feet, and to delineate the arms from each other and the stomach.

Their flat back and inability to stand on their carved feet suggest that these figures were meant to lie down. While today they are featureless and remain the stark white of the marble, traces of paint allow us to know that they were once colored. Paint would have been applied on the face to demarcate the eyes, mouth, and hair. Dots were used to decorate the figures with bracelets and necklaces.

Cycladic Male Figures

Male figures are also found in Cycladic grave sites. These figures differ from the females, as the male typically sits on a chair and plays a musical instrument, such as the pipes or a harp. Harp players, like the one in the example below, play the frame harp, a Near Eastern ancestor of the modern harp.

The figures, their chairs, and instruments are all carved into elegant, cylindrical shapes. Like the female figures, the shape of the male figure is reliant on geometric shapes and flat planes. The incised lines provide details (such as toes), and paint added distinctive features to the now-blank faces.

Other Cycladic Figures

While reclining female and seated male figurines are the most common Cycladic sculptures discovered, other forms were produced, such as animals and abstracted humanoid forms. Examples include the terra cotta figurines of bovine animals (possibly oxen or bulls) that date to 2200–2000 BCE, and small, flat sculptures that resemble female figures shaped like violins; these date to the Grotta–Pelos culture, also known as Early Cycladic I (c. 3300–2700 BCE). Like other Cycladic sculptures discovered to date, the purposes of these figurines remain unknown.

The Minoans

The Protopalatial period of Minoan civilization (1900 to 1700 BCE) saw the establishment of administrative centers on Crete; the Neopalatial Period (1700 to 1450 BCE) can be considered the apex, or height, of Minoan civilization.

Key Points

- The Minoan civilization was named after the mythical King Minos, because the first excavator, Sir Arthur Evans , mistook the many rooms and corridors of the administrative palace of Knossos to be the labyrinth in which Minos kept the Minotaur.

- The Protopalatial period (1900–1700 BCE) saw the establishment of administrative centers on the island of Crete. The identifying features of Minoan civilization—extensive sea trade and the building of communal civic centers—are first seen on the island during this time.

- The Protopalatial period ended in 1700 BCE when the palaces of the island were destroyed and life on the island was significantly disrupted. The unknown cataclysmic event is believed to be either an earthquake or an invasion.

- During the Neopalatial period (1700–1450 BCE), the Minoans recovered from the cataclysm and reached the height of their civilization, eventually controlling the major trade routes in the Mediterranean.

Key Terms

- labyrinth: A maze, especially underground or covered.

- minotaur: A monster with the head of a bull and the body of a man.

- Linear A: A syllabary (set of written characters representing syllables) used to write the as-yet-undeciphered Minoan language, and an apparent predecessor to other scripts.

Discovery and Excavation

The ancient sites on the island of Crete were first excavated in the early 1900s by the British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans. Evans excavated the site of Knossos, where he discovered a palace. From this fact and related points, he decided to name the civilization after the mythical King Minos.

The many rooms of the palace at Knossos were so oddly shaped and disordered to Evans that they reminded him of the labyrinth of the Minotaur. According to myth, Minos’ wife had an illicit union with a white bull, which lead to the birth of a half bull and half man, known as the Minotaur. King Minos had his court artist and inventor, Daedalus, build an inescapable labyrinth for the Minotaur to live in.

Archaeological evidence dates the arrival of the earliest inhabitants of Crete in approximately 6000 BCE. Over the next four thousand years the inhabitants developed a civilization based on agriculture, trade, and production. The Minoan’s civilization on Crete existed during the Bronze Age, from 3000 to 1100 BCE, although the Mycenaeans from Greece invaded the island in the mid-1400s BCE and occupied it for the last centuries before the Greek Dark Age.

The Minoans were known as great seafarers. They traded extensively throughout the Mediterranean region.

Protopalatial Period

The Protopalatial Period is considered the civilization’s second phase of development, lasting from 1900 to 1700 BCE. During this time the major sites on the island were developed, including the palatial sites of Knossos, Phaistos, and Kato Zakros, which were the first palaces or administrative centers built on Crete.

These civic centers appear to denote the emergence of a collective community governing system, instead of system in which a king ruled over each town. During this period the Minoan trade network expanded into Egypt and the Near East; the first signs of writing, the still undeciphered language Linear A, appear. The period ended with a cataclysmic event, perhaps an earthquake or an invasion, which destroyed the palace centers.

Neopalatial Period

The Neopalatial period occurred from 1700 to 1450 BCE, during which time the Minoans saw the height of their civilization. Following the destruction of the first palaces in approximately 1700 BCE, the Minoans rebuilt these centers into the palaces that were first excavated by Sir Arthur Evans.

During this period, Minoan trade increased and the Minoans were considered to rule the Mediterranean trading routes between Greece, Egypt, Anatolia, the Near East, and perhaps even Spain. The Minoans began to settle in colonies away from Crete, including on the islands of the Cyclades, Rhodes, and in Egypt.

Minoan Architecture

Minoan palace centers were divided into numerous zones for civic, storage, and production purposes; they also had a central, ceremonial courtyard.

Key Points

- The palaces excavated on Crete functioned more as administrative centers with rooms for civic functions, storage, workshops, and shrines located around a central, ceremonial courtyard.

- The palaces have no fortification walls, suggesting a lack of enemies and conflict, although the natural surroundings provide a high level of protection, and the multitude of rooms creates a continuous, protective façade.

- Minoan columns were uniquely shaped, constructed from wood, and painted. They are tapered at the bottom, larger at the top, and fitted with a bulbous, pillow-like capital.

- The complex at Phaistos bears many similarities with its counterpart at Knossos, although it is smaller.

- Minoan builders rebuilt new complexes atop older ones in the aftermath of damaging earthquakes.

Key Terms

- pithoi: (Singular: pithos) Large storage jars for liquids—oil, wine, and water—and grains.

- labyrinth: A maze, especially underground or covered.

- fresco: A water-based painting applied to wet or dry plaster.

- capital: The topmost part of a column.

The most well known and excavated architectural buildings of the Minoans were the administrative palace centers, although small temple structures are known.

When Sir Arthur Evans first excavated at Knossos, not only did he mistakenly believe he was looking at the legendary labyrinth of King Minos, he also thought he was excavating a palace. However, the small rooms and excavation of large pithoi, storage vessels, and archives led researchers to believe that these palaces were actually administrative centers. Even so, the name became ingrained, and these large, communal buildings across Crete are known as palaces.

Although each one is unique, they share similar features and functions. The largest and oldest palace centers are at Knossos, Malia, Phaistos, and Kato Zakro.

The Complex at Knossos

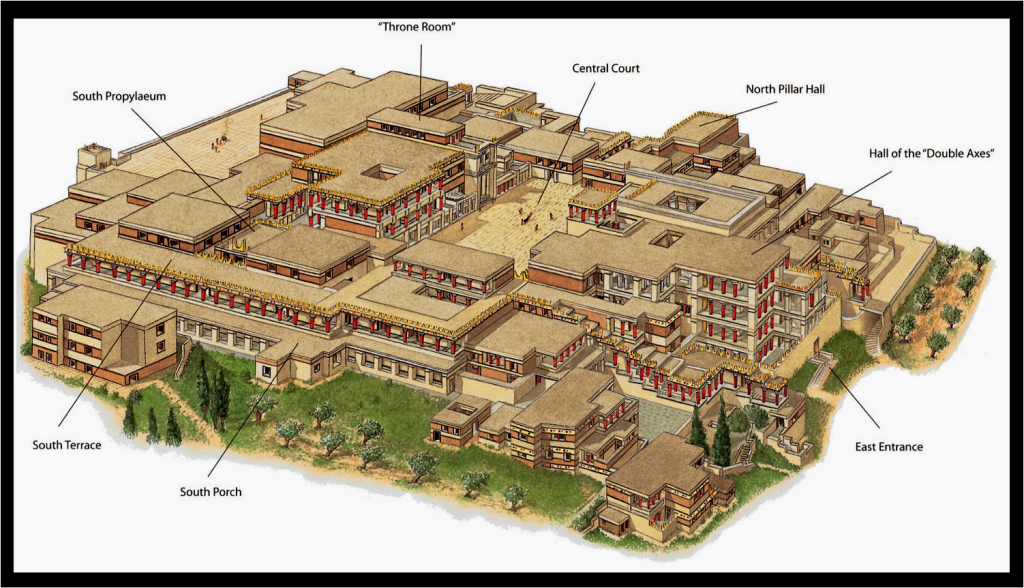

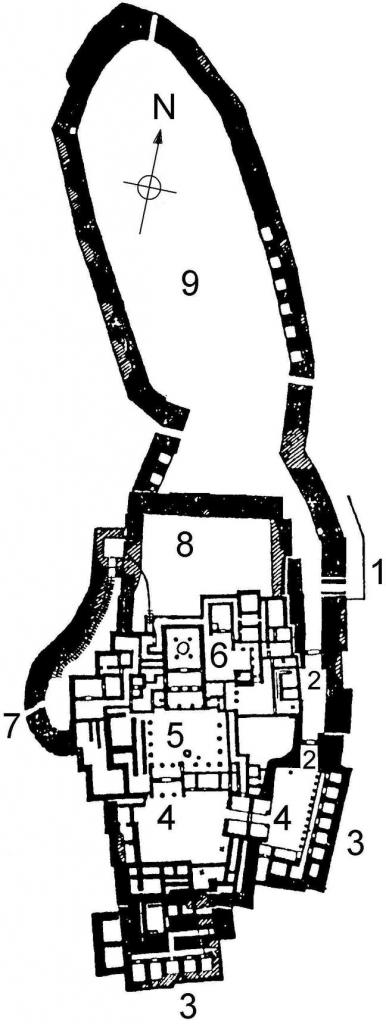

The complex at Knossos provides an example of the monumental architecture built by the Minoans. The most prominent feature on the plan is the palace’s large, central courtyard. This courtyard may have been the location of large ritual events, including bull leaping, and a similar courtyard is found in every Minoan palace center.

Several small tripartite shrines surround the courtyard. The numerous corridors and rooms of the palace center create multiple areas for storage, meeting rooms, shrines, and workshops.

The absence of a central room and living chambers suggest the absence of a king and, instead, the presence and rule of a strong, centralized government. The palaces also have multiple entrances that often take long paths to reach the central courtyard or a set of rooms. There are no fortification walls, although the multitude of rooms creates a protective, continuous façade. While this provides some level of fortification, it also provides structural stability for earthquakes. Even without a wall, the rocky and mountainous landscape of Crete and its location as an island creates a high level of natural protection.

The palaces are organized not only into zones along a horizontal plane, but also have multiple stories. Grand staircases decorated with columns and frescos connect to the upper levels of the palaces, only some parts of which survive today. Interior spaces have wells which are open to the sky to provide ventilation and light. The Minoans also created careful drainage systems and cisterns for collecting and storing water, as well as sanitation.

Their architectural columns are uniquely constructed and easily identified as Minoan. They are constructed from wood, as opposed to stone, and are tapered at the bottom. They stood on stone bases and had large, bulbous tops, now known as cushion capitals. The Minoans painted their columns bright red and the capitals were often painted black.

Minoan Painting

Minoan Painting

Minoan painting is distinguished by its vivid colors and curvilinear shapes that bring a liveliness and vitality to scenes.

Key Points

- The fresco known as Bull Leaping, found in the palace of Knossos, is one of the seminal Minoan paintings. It depicts the Minoan culture ‘s fascination with the bull and the unique event of bull leaping—all painted in the distinctive Minoan style.

- The Minoan city of Akrotiri on the island of Thera was destroyed by a volcanic eruption that preserved the wall paintings in the town’s homes. One fresco, known as Flotilla, depicts a highly developed society.

- Kamares ware is pottery made from a fine clay. These vessels are painted with marine scenes and abstract flowers, shapes, and geometric lines.

- Marine-style vase painting depicts marine life and scenes with organic shapes that fill the entire surface of the pot, using a technique known as horror vacui. Unlike Kamares ware, Marine-style scenes are painted in dark colors on a light surface.

Key Terms

- horror vacui: Latin, meaning fear of empty space; this is also the name for a style of painting when the entire surface of a space is filled with patterns and figures.

- fresco: In painting, the technique of applying water-based pigment to plaster.

- buon fresco: A more durable mural painting technique in which alkaline resistant pigments, ground in water, are applied to plaster when it is still wet, as opposed to fresco-secco when the plaster has been allowed to dry and is remoistened.

- flying gallop: an image of an animal depicted with all four feet off the ground at once to suggest speed and force.

Fresco

The Minoans decorated their palace complexes and homes with buon fresco wall paintings which have remained colorful and intact with the wall for centuries.

In the Minoan variation, the stone walls are first covered with a mixture of mud and straw, then thinly coated with lime plaster, and lastly with layers of fine plaster. The Minoan color palette is based in earth tones of white, brown, red, and yellow. Black and vivid blue are also used. These color combinations reflect the colors of nature that surrounded the Minoan people and create vivid and rich decoration.

Because the Minoan “alphabet”, known as Linear A, has yet to be deciphered, scholars must rely on the culture’s visual art to provide insights into Minoan life. The frescoes discovered in locations such as Knossos and Akrotiri inform us of the plant and animal life of the islands of Crete and Thera (Santorini), the common styles of clothing, and the activities the people practiced. For example, men wore kilts and loincloths. Women wore short-sleeve dresses with flounced skirts whose bodices were open to the navel, allowing their breasts to be exposed.

Bull Leaping (aka Toreador) Fresco at Knossos

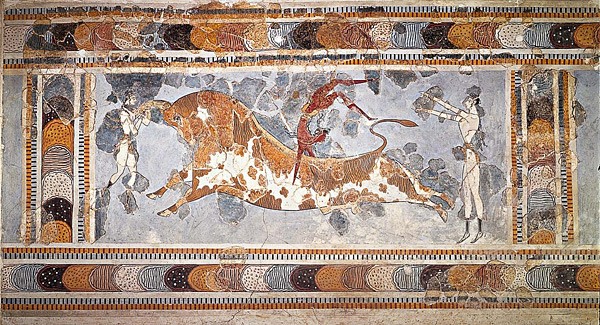

Fragments of frescoes found at Knossos provide us with glimpses into Minoan culture and rituals. A fresco found on an upper story of the palace has come to be known as Bull Leaping. The image depicts a bull in flying gallop with one person at his horns, another at his feet, and a third, whose skin color is brown instead of white, inverted in a handstand leaping over the bull.

While the different skin color of the figures may differentiate male (dark) and female (light) figures, the similarity of their clothing and body shapes (lean with few curves) suggest that the figures may all be male. The figures participate in an activity known as bull-leaping.

The human figures are stylized with narrow waists, broad shoulders, long, slender, muscular legs, and cylindrical arms. Unlike the twisted – or composite – perspective seen in Egyptian or Ancient Near Eastern works of art, these figures are shown in full profile, an element that adds to the lifelike quality of the scene.

Although the specifics of bull leaping remain a matter of debate, it is commonly interpreted as a ritualistic activity performed in connection with bull worship. In most cases, the leaper would literally grab a bull by his horns, which caused the bull to jerk his neck up and back. This motion gave the leaper the momentum necessary to perform somersaults and other acrobatic tricks or stunts. Bull leaping appears to divide these steps between two participants, with a third extending his or her arms, possibly to catch the leaper.

Thera

The Minoans settled on other islands besides Crete, including the volcanic, Cycladic island of Thera (present-day Santorini). The volcano on Thera erupted in mid-second millennium BCE and destroyed the Minoan city of Akrotiri. Akrotiri was entombed by pumice and ash and since its rediscovery has been referred to as the Minoan Pompeii. The frescoes on Akrotiri were preserved by the blanketing volcanic ash.

The wall paintings found on Thera provide significant information about Minoan life and culture, depicting a highly developed society. A fresco commonly called Flotilla or Akrotiri Ship Procession represents a culture adept at a variety of seafaring occupations.

Differences in clothing styles could refer to different ranks and roles in society. Deer, dolphins, and large felines point to a sense of biodiversity among the islands of the Minoan civilization.

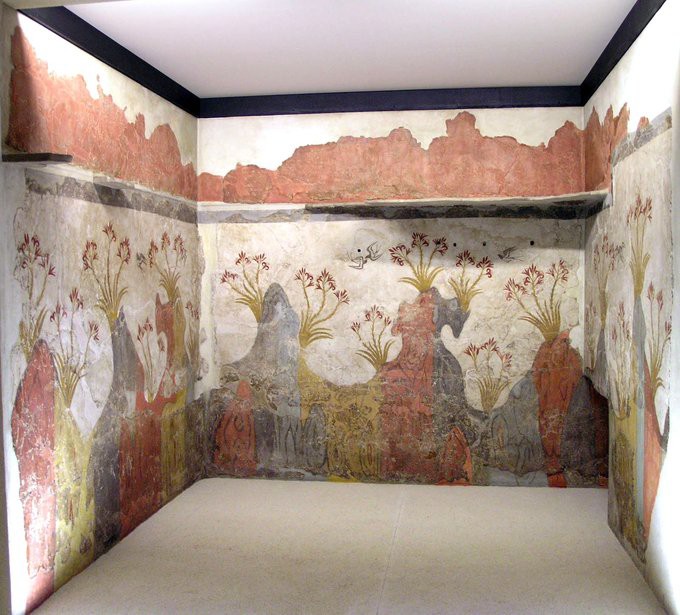

A wall painting known as the Landscape with Swallows, or as the Spring Fresco, depicts a whimsical, hilly landscape with lilies sprouting from the ground. Sparrows, painted in blue, white, and red, swoop around the landscape. The lilies sway gracefully and the hills create an undulating rhythm around the room. The fresco does not depict a naturalistic landscape, but instead suggests an essence of the land and nature whose liveliness is enhanced through the colors and curvilinear lines. It evokes the integrated quality of the Minoans culture with the natural environment.

Vase Painting

Minoan ceramics and vase painting are uniquely stylized and are similar in artistic style to Minoan wall painting. As with Minoan frescoes, themes from nature and marine life are often depicted on their pottery. Similar earth-tone colors are used, including black, white, brown, red, and blue.

Kamares ware, a distinctive type of pottery painted in white, red, and blue over a black backdrop, is created from a fine clay. The paintings depict marine scenes, as well as abstract floral shapes, and they often include abstract lines and shapes, including spirals and waves. These stylized, floral shapes include lilies, palms, papyrus, and leaves that fill the entire surface of the pot with bold designs. The pottery is named for the location where it was first found in the late nineteenth century—a cave sanctuary at Kamares, on Mount Ida. This style of pottery is found throughout the island of Crete as well in a variety of locations on the Mediterranean.

The Marine style emerged during the late Minoan period. As the name suggests, the decorations on these vessels take their cue from the sea. The vessels are almost entirely covered with sea creatures such as dolphins, fish, and octopi, along with seaweed, rock, and sponges.

Unlike their Kamares ware predecessors, the light and dark color scheme is inverted: the figures are dark on a light background. Like the landscape frescoes at Thera, these paintings demonstrate a keen understanding and intimate knowledge of the marine environment.

In the Marine-style Octopus Vase from the city of Palaikastro, the octopus wraps around the jug, mimicking and accentuating its round shape. The octopus is painted in great detail, from each of its distinct stylized suckers to its bulbous head and the extension of its long tentacles. The surface of this vessel is covered by the main image; bits of seaweed fill the negative space.

This filling of the empty space with additional images or designs is another characteristic of Minoan Marine-style pottery. The style is known as horror vacui, which is Latin for fear of empty space. The same aesthetic is seen later, in Greek Geometric pottery.

Minoan Sculpture

Minoan sculpture consists of figurines that reflect the culture’s artistic style and important aspects of daily life.

Key Points

- Most known Minoan sculptures are small scale. They range from single figures, often frontal, to figure groups that include both people and animals. The wide variety of materials used for these figurines represent the extent of the Minoan trade network throughout the Mediterranean.

- The Snake Goddess statue from Knossos represents an important female figure in Minoan culture. Due to her connection with snakes and felines, as well as her bare breasts, she is perhaps an earth goddess or a Minoan priestess.

- The Bull Leaper demonstrates the Minoan use of bronze in art as well as highlighting the importance of the bull in Minoan sculpture and artistic style.

- An ivory bull leaper from Knossos demonstrates another position the acrobat’s body assumed during the act.

- The Palaikastro Kouros is a rare example of a large-scale Minoan sculpture. Its size and rare materials lead experts to believe that it was used as a cult image.

Key Terms

- lost-wax casting: The most common method of using molten metal to make hollow, one-of-a-kind sculptures. When heat is applied to the clay mold, the wax layer within melts and forms channels, which the artist then fills with molten metal.

- faience: A low-fired, opaque, quartz ceramic that creates a glass-like material in bright shades of blue, green, white, and brown that originates from Ancient Egypt.

- chthonic: Dwelling within or under the earth.

- curvilinear: Having bends; curved; formed by curved lines.

As with their painting, Minoan sculpture demonstrates stylistic conventions including curvilinear forms; active, energized scenes; and long-limbed humans with broad shoulders and narrow waists. Women are often depicted in large, long, layered skirts that accentuate their hips. So far, the majority of sculptures and figurines found during Minoan excavations have been small scale.

Materials

The small-scale sculptures of the Minoans were produced in many different materials including ivory, gold, faience, and bronze. The variety of materials acknowledges the extensive trade network established by the Minoans. For instance, faience, a quartz ceramic, is an Egyptian material. Its presence in sculpture found on Crete demonstrates that the material was shipped raw from Egypt to Crete, where it was then formed to create Minoan sculpture. Bronze was an important material in Minoan culture and many figurines were produced in this medium, mostly created using the lost-wax casting technique.

Snake Goddess

One figurine, known as the Snake Goddess, depicts a woman with open arms who holds a snake in each hand, with a feline sitting on her head. The purpose or function of the statue is unknown, although it is believed that she may have been an earth goddess or priestess.

The snakes are considered chthonic animals—related to the earth and the ground— and are often symbols of earth deities. Furthermore, the Snake Goddess is dressed in a layered skirt with a tight bodice, covered shoulders, and exposed breasts. The prominence of her breasts may suggest that she is fertility figure. Although her function remains unknown, the figure’s significance to the culture is unquestionable.

Other figures in similar poses and outfits have also been found among Minoan ruins.

Bull Leaper

The Bull Leaper bronze, depicting a bull and an acrobat, was created as a single group. The figures are similar in style and position, as seen in several bull-leaping frescoes, including one from the palatial complex at Knossos.

The bull stands frozen in a flying gallop, while a leaper appears to be flipping over his back. The acrobat’s feet are planted firmly on the bull’s rump, and the figure bends backwards with its arms planted on the bull’s head, perhaps preparing to launch off of the bull. The two figures, bull and leaper, mirror each other, as the bull’s back sways in the gallop and the figure’s back is arched in a deep back bend. The object is made with curvilinear lines and the positioning of both figures adds a high degree of movement and action that was commonly found in Minoan art.

The Minoan culture appears by the artifacts left behind to be a peaceful, nature-loving, athletic culture which existed in an idyllic setting for centuries.

Mycenaean Architecture

The architecture of Mycenaean citadel sites reflects the war-like culture and its constant need for protection and fortification.

Key Points

- The city of Mycenae was the center of Mycenaean culture. It is especially known for its protective gateway, the Lion Gate, and the Treasury of Atreus, an example of a tholos tomb. Mycenaean architecture reflects their warring society. A wide, strong wall built from large, roughly cut stones (known as cyclopean masonry) was one method of protection, as was limited access to citadel sites and well-protected gates.

- Since a lintel over a doorway could not support the wall above it without collapsing, the Mycenaeans used corbeled vaults and a relieving triangle over lintels to redistribute the weight off the horizontal beam and into the supporting walls.

- The central feature of a Mycenaean citadel site was the megaron, a room that functioned as the king’s audience chamber. The megaron is entered through a porch with two columns and the main room included four columns around a central hearth.

- Uniformity among the citadel sites throughout the Mycenaean civilization allow us to easily compare components such as megarons.

Key Terms

- post-and-lintel: A simple construction method using a header as the horizontal member over a building void supported at its ends by two vertical columns.

- corbel: A structural member jutting out of a wall to carry a superincumbent weight.

- ashlar: Masonry made of large, square-cut stones.

- megaron: The rectangular great hall in a Mycenaean building, usually supported with pillars.

- cyclopean masonry: A type of stonework found in Mycenaean architecture, built with massive limestone boulders that are roughly fitted together with minimal clearance between adjacent stones and no use of mortar.

- citadel: The core fortified area of a town or city.

Mycenaean culture can be summarized by its architecture, whose remains demonstrate the Mycenaeans’ war-like culture and the dominance of citadel sites ruled by a single ruler. The Mycenaeans populated Greece and built citadels on high, rocky outcroppings that provided natural fortification and overlooked the plains used for farming and raising livestock. The citadels vary from city to city but each share common attributes, including building techniques and architectural features.

Building Techniques

The walls of Mycenaean citadel sites were often built with ashlar and massive stone blocks. The blocks were considered too large to be moved by humans and were believed by ancient Greeks to have been erected by the Cyclopes—one-eyed giants. Due to this ancient belief, the use of large, roughly cut, ashlar blocks in building is referred to as Cyclopean masonry. The thick Cyclopean walls reflect a need for protection and self-defense since these walls often encircled the citadel site and the acropolis on which the site was located.

Corbel Arch

The Mycenaeans also relied on new techniques of building to create supportive archways and vaults. A typical post and lintel structure is not strong enough to support the heavy structures built above it. Therefore, a corbeled (or corbel) arch is employed over doorways to relieve the weight on the lintel.

The corbel arch is constructed by offsetting (cantilevering) successive courses of stone (or brick) at the springline of the walls so that they project towards the archway’s center from each supporting side, until the courses meet at the apex of the archway (often, the last gap is bridged with a flat stone). The corbel arch was often used by the Mycenaeans in conjunction with a relieving triangle, which was a triangular block of stone that fit into the recess of the corbeled arch and helped to redistribute weight from the lintel to the supporting walls. The triangular space may have been left open in some structures.

Citadel Sites

Mycenaean citadel sites were centered around the megaron, a reception area for the king. The megaron was a rectangular hall, fronted by an open, two-columned porch. It contained a more or less central open hearth, which was vented though an oculus in the roof above it and surrounded by four columns. The architectural plan of the megaron became the basic shape of Greek temples, demonstrating the cultural shift as the gods of ancient Greece took the place of the Mycenaean rulers.

Citadel sites were protected from invasion through natural and man-made fortification. In addition to thick walls, the sites were protected by controlled access. Entrance to the site was through one or two large gates, and the pathway into the main part of the citadel was often controlled by more gates or narrow passageways. Since citadels had to protect the area’s people in times of warfare, the sites were equipped for sieges. Deep water wells, storage rooms, and open space for livestock and additional citizens allowed a city to access basic needs while being protected during times of war.

Mycenae

The citadel site of Mycenae was the center of Mycenaean culture. It overlooks the Argos plain on the Peloponnesian peninsula, and according to Greek mythology was the home to King Agamemnon.

The site’s megaron sits on the highest part of the acropolis and is reached through a large staircase. Inside the walls are various rooms for administration and storage along with palace quarters, living spaces, and temples. A large gravesite, known as Grave Circle A, is also built within the walls.

The main approach to the citadel is through the Lion Gate, a cyclopean-walled entrance way. The gate is 20 feet wide, which is large enough for citizens and wagons to pass through, but its size and the walls on either side create a tunneling effect that makes it difficult for an invading army to penetrate.

The gate is famous for its use of the relieving arch, a corbeled arch that leaves an opening and lightens the weight carried by the lintel. The Lion Gate received its name from its decorated relieving triangle of lions one either side of a single column. This composition of lions or another feline animal flanking a single object is known as a heraldic composition. The lions represent cultural influences from the Ancient Near East. Their heads are turned to face outwards and confront those who enter the gate.

Mycenae is also home to a subterranean beehive-shaped tomb (also known as a tholos tomb) that was located outside the citadel walls. The tomb is known today as the Treasury of Atreus, due to the wealth of grave goods found there. This tomb and others like it are demonstrations of corbeled vaulting that covers an expansive open space. The vault is 44 feet high and 48 feet in diameter. The tombs are entered through a narrow passageway known as a dromos and a post-and-lintel doorway topped by a relieving triangle.

Tiryns

The citadel site of Tiryns, another example of Mycenaean fortification, was a hill fort that has been occupied over the course of 7000 years. It reached its height between 1400 and 1200 BCE, when it was one of the most important centers of the Mycenaean world. Its most notable features were its palace, its Cyclopean tunnels, its walls, and its tightly controlled access to the megaron and main rooms of the citadel.

Just a few gates provide access to the hill but only one path leads to the main site. This path is narrow and protected by a series of gates that could be opened and closed to trap invaders. The central megaron is easy to locate, and it is surrounded by various palatial and administrative rooms. The megaron is accessed through a courtyard that is decorated on three sides with a colonnade.

The famous megaron has a large reception hall, the main room of which had a throne placed against the right wall and a central hearth bordered by four wooden columns that served as supports for the roof. It was laid out around a circular hearth surrounded by four columns. Although individual citadel sites varied to a degree, their overall uniformity allows us to compare design elements easily. For example, the hearth of the megaron at the citadel of Pylos provides an idea of how its counterpart at Tiryns appears.

Mycenaean Metallurgy

The Mycenaeans were masterful metalworkers, as their gold, silver, and bronze daggers, drinking cups, and other objects demonstrate.

Key Points

- Grave Circle A and B, at Mycenae, are a series of shaft graves enclosed by a wall from the 16th century BCE. These grave sites were originally excavated by Heinrich Schleimann, and the grave goods found there demonstrate the incredible skill Mycenaeans possessed in metalwork.

- Gold death masks were commonly placed over the face of the wealthy deceased. These death masks record the main features of the dead and are made with repoussé, a metalworking technique. When compared to other masks, the Death Mask of Agamemnon is most likely a fake.

- Bronze daggers inlaid with gold, silver, and niello are a common grave good found at Mycenaean burial sites. These daggers represent international trade and cultural connections between the Mycenaeans and the Minoans, Egyptians, and Near Eastern cultures.

- Rhytons were also crafted out of gold and silver. Some, such as the Silver Siege Rhyton, were used for ritual libations, or the offering of liquids.

- Other objects of gold, silver, and bronze have been excavated from Mycenaean grave sites and cities, including armor, jewelry, signet rings, and seals.

Key Terms

- diadem: A crown or headband worn as a symbol of sovereignty.

- repoussé: A metalworking technique in which a thin sheet of malleable metal is shaped by hammering from the reverse side to create a design in low relief.

- rhyton: A container, having a base in the form of a head, from which fluids are intended to be drunk.

- niello: Any of various black metal alloys, made of sulphur with copper, silver or lead, used to create decorative designs on other metals.

Grave Circle A at Mycenae

Grave Circle A is a set of graves from the sixteenth century BCE located at Mycenae. The grave circle was originally located outside the walls of the city but was later encompassed inside the walls of the citadel when the city’s walls were enlarged during the thirteenth century BCE.

The grave circle is surrounded by a second wall and only has one entrance. Inside are six tombs for nineteen bodies that were buried inside shaft graves. The shaft graves were deep, narrow shafts dug into the ground.

The body would be placed inside a stone coffin and placed at the bottom of the grave along with grave goods. The graves were often marked by a mound of earth above them and grave stele.

The gravesite was excavated by Heinrich Schleimann in 1876, who excavated ancient sites such as Mycenae and Troy based on the writings of Homer and was determined to find archaeological remains that aligned with observations discussed in the Iliad and the Odyssey. The archaeological methods of the nineteenth century were different than those of the twenty-first century and Schleimann’s desire to discover remains that aligned with mythologies and Homeric stories did not seem as unusual as it does today. Upon excavating the tombs, Schleimann declared that he found the remains of Agamemnon and many of his followers, a claim discounted by modern archaeology.

Grave Circle B

An additional grave circle, Grave Circle B, is also located at Mycenae, although this one was never incorporated into the citadel site. The two grave circles were elite burial grounds for the ruling dynasty. The graves were filled with precious items made from expensive material, including gold, silver, and bronze.

The amount of gold, silver, and previous materials in these tombs not only depict the wealth of the ruling class of the Mycenae but also demonstrates the talent and artistry of Mycenaean metalworking. Reoccurring themes and motifs underline the culture’s propensity for war and the cross-cultural connections that the Mycenaeans established with other Mediterranean cultures through trade, including the Minoans, Egyptians, and even the Orientalizing style of the Ancient Near East

Gold Death Masks

Repoussé death masks were found in many of the tombs. The death masks were created from thin sheets of gold, through a careful method of metalworking to create a low relief.

These objects are fragile, carefully crafted, and laid over the face of the dead. Schleimann called the most famous of the death masks the Mask of Agamemnon, under the assumption that this was the burial site of the Homeric king. The mask depicts a man with a triangular face, bushy eyebrows, a narrow nose, pursed lips, a mustache, and stylized ears.

This mask is an impressive and beautiful specimen but looks quite different from other death masks found at the site. The faces on other death masks are rounder; the eyes are more bulbous; and at least one bears a hint of a smile. None of the other figures have a mustache or even the hint of beard.

In fact, the mustache looks distinctly nineteenth century and is comparable to the mustache that Schleimann himself had. The artistic quality between the Mask of Agamemnon and the others seems dramatically different. Despite these differences, the Mask of Agamemnon has inserted itself into the story of Mycenaean art.

Bronze Daggers

Decorative bronze daggers found in the grave shafts suggest there were multicultural influences on Mycenaean artists. These ceremonial daggers were made of bronze and inlaid in silver, gold, and niello with scenes that were clearly influenced from foreign cultures.

Two daggers that were excavated depict scenes of hunts, which suggest an Ancient Near East influence. One of these scenes depicts lions hunting prey, while the other scene depicts a lion hunt. The portrayal of the figures in the lion hunt scene draws distinctly from the style of figures found in Minoan painting. These figures have narrow waists, broad shoulders, and large, muscular thighs.

The scene between the hunters and the lions is dramatic and full of energy, another Minoan influence. Another dagger depicts the influence of Minoan painting and imagery through the depiction of marine life, and Egyptian influences are seen on a dagger filled with lotus and papyrus reeds along with fowl.

Gold and Silver Rhytons (Drinking Cups)

A variety of gold and silver drinking cups have also been found in these grave shafts. These include a rhyton in the shape of a bull’s head, with golden horns and a decorative, stylized gold flower, made from silver repoussé.

Other cups include the golden Cup of Nestor, a large two handle cup that Schleimann attributed to the legendary Mycenaean hero Nestor, a Trojan War veteran who plays a peripheral role in The Odyssey.

Other Objects

Additional gold trinkets include signet rings that depict images of hunts, combat, and animals, along with other decorative jewelry, such as bracelets, earrings, pendants, and diadems (headbands designating their wearers’ sovereign status).

Bronze armor, including breastplates and helmets, were also uncovered in excavations of the tomb sites.

There are few examples of large-scale, freestanding sculptures from the Mycenaeans. A painted plaster head of a female—perhaps depicting a priestess, goddess, or sphinx —is one of the few examples of large-scale sculpture. The head is painted white, suggesting that it depicts a female. A red band wraps around her head with bits of hair underneath. The eyes and eyebrows are outlined in blue, the lips are red, and red circles surrounded by small red dots are on her cheeks and chin.