36 Abstract Expressionism

The Development of Abstract Expressionism

Abstract expressionism was an American, post–World War II art movement.

Learning Objectives

- Explain the abstract expressionist movement of the 1940s.

Key Points

- Abstract expressionism has an image of being rebellious, anarchic, highly idiosyncratic, and nihilistic. In practice, the term is applied to any number of artists working (mostly) in New York who had quite different styles, and even to work that is neither especially abstract nor expressionist.

- Although it is true that spontaneity or the impression of spontaneity characterized many of the abstract expressionists works, most of these paintings involved careful planning, especially since their large size demanded it.

- Abstract expressionist paintings share certain characteristics, including the use of large canvases and an all-over approach, in which the whole canvas is treated with equal importance.

Key Terms

- New York School: The New York School (synonymous with abstract expressionist painting) was an informal group of American poets, painters, dancers, and musicians active in the 1950s and 1960s in New York City.

Abstract Expressionism Overview

Abstract expressionism was an American post–World War II art movement. Although the term abstract expressionism was first applied to American art in 1946 by the art critic Robert Coates, it had been used previously in Germany’s Der Sturm magazine in 1919.

Abstract expressionism is derived from the combination of the emotional intensity and self-denial of the German expressionists with the anti-figurative aesthetic of the European abstract schools, such as Futurism, the Bauhaus, and Synthetic Cubism. Additionally, it has an image of being rebellious, anarchic, highly idiosyncratic, and sometimes nihilistic. In practice, the term is applied to any number of artists who worked (mostly) in New York during the 1940s and 50s.

Abstract expressionism has many stylistic similarities to the Russian artists of the early 20th century, such as Wassily Kandinsky. Although it is true that spontaneity or the impression of spontaneity characterized many of the abstract expressionists’ works, in reality most of these paintings involved careful planning, especially since their large size demanded it. In many instances, abstract art implied the expression of ideas that concern the spiritual, the unconscious, and the mind.

Characteristics of Abstract Expressionist Painting

Abstract Expressionism expanded and developed the definitions and possibilities that artists had available in the creation of new works of art. Although Abstract Expressionism spread quickly throughout the United States, the major centers of this style were New York and California. Abstract Expressionist paintings share certain characteristics, including the use of large canvases and an all-over approach, in which the whole canvas is treated with equal importance (as opposed to the center being of more interest than the edges).

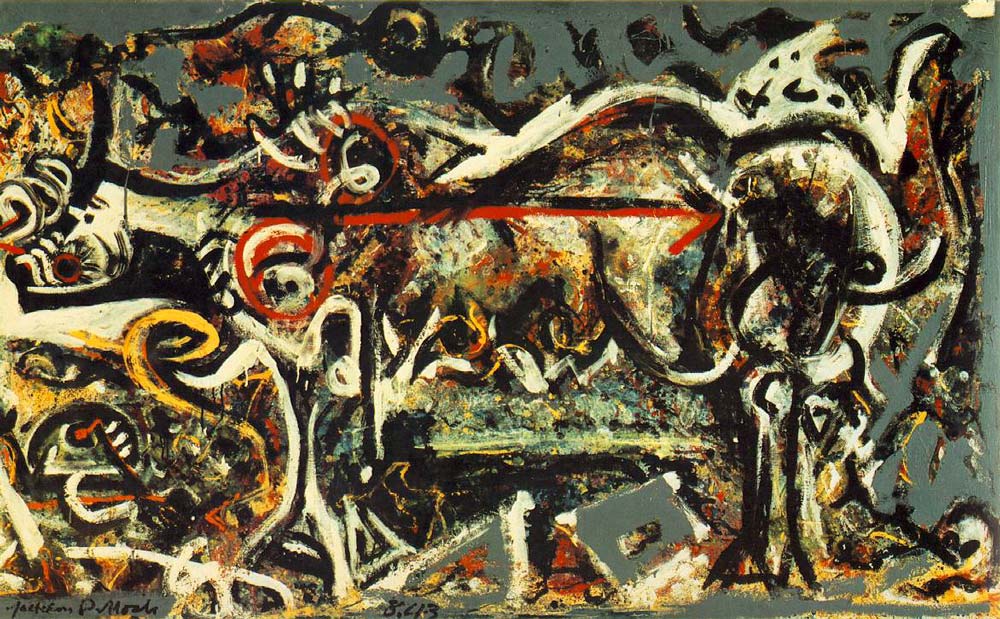

Jackson Pollock is known for his techniques in action painting, a style of Abstract Expressionism in which paint is spontaneously dripped, splashed, or smeared onto the canvas rather than being carefully applied, as seen in this painting done in 1948.

Jackson Pollock’s energetic action paintings, so-called by critic Harold Rosenberg in 1952 for the gesturally active quality of the brushwork, are different both technically and aesthetically from the violent and grotesque Women series of Willem de Kooning. In contrast to the emotional energy and gestural surface marks of Pollock and de Kooning, the color-field painters initially appeared to be cool and austere, eschewing the individual mark in favor of large, flat areas of color, which these artists considered to be the essential nature of visual abstraction, along with the actual shape of the canvas. In later years, color-field painting has proven to be both sensual and deeply expressive, albeit in a different way from gestural Abstract Expressionism.

Abstract Expressionism flourished after World War II until the early 1960s. It is characterized by the view that art should be non-representational and chiefly improvisational. The canvas as the arena became a credo of action painting, while the integrity of the picture plane became a credo of the color-field painters.

The post-World War II era benefited some of the artists who were recognized early on by art critics. Some artists from New York, such as Norman Bluhm and Sam Francis, took advantage of the GI Bill and left for Europe, to return later with acclaim.

Many artists from all across the U.S. arrived in New York City to seek recognition, and by the end of the decade the list of artists associated with the New York School had greatly increased. Painters, sculptors, and printmakers created art that was termed action painting, or color-field painting; Fluxus, hard-edge painting, pop art, minimal art and lyrical abstraction, among other styles and movements followed Abstract Expressionism.

New York

During the period leading up to and during World War II, modernist artists, writers, and poets, as well as important collectors and dealers, fled Europe and the onslaught of the Nazis for safe haven in the United States. New York replaced Paris as the new center of the art world.

The 1940s in New York City heralded the triumph of American Abstract Expressionism—a modernist movement that combined lessons learned from Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Surrealism, Joan Miró, Cubism, Fauvism, and early Modernism via the great teachers who arrived in America, like Hans Hofmann, Josef and Anni Albers from Germany, and John D. Graham from Russia.

Graham’s influence on American art during the early 1940s was particularly visible in the work of Arshile Gorky, Willem de Kooning, and Jackson Pollock. Gorky’s contributions to American and world art are difficult to overestimate. His works—such as The Liver is the Cock’s Comb, The Betrothal II, and One Year the Milkweed—immediately prefigured Abstract Expressionism.

Gorky was originally Armenian having escaped the Armenian Genocide with his mother by going to a Russian-controlled area. There his mother starved to death; Gorky eventually escaped to the United States. His earlier work was figurative, but in the U.S. he began the nonrepresentational art that would be so influential to other Abstract Expressionists.

Jackson Pollock

During the late 1940s, Jackson Pollock’s radical approach to painting revolutionized the potential for all contemporary art that followed him. To some extent, Pollock realized that the journey toward making a work of art was as important as the work of art itself.

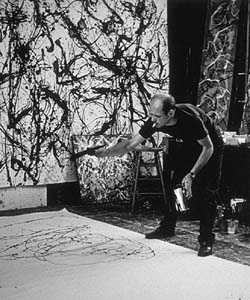

Pollock redefined what it was to produce art. His move away from easel painting and conventionality was a liberating signal to the artists of his era and to all that came after. Artists realized that Jackson Pollock’s process—the placing of unstretched raw canvas on the floor where it could be attacked from all four sides using artist materials and industrial materials—essentially took making art beyond any prior boundary.

Jackson Pollock and Action Painting

Action painting, created by Jackson Pollock, is a style in which paint is spontaneously splattered, smeared, or dripped onto the canvas.

Learning Objectives

- Describe Jackson Pollock’s method of action painting.

Key Points

- Action painting was developed as part of the abstract expressionism movement that took place in post–World War II America, especially in New York, during the 1940s through until the early 1960s.

- Action painting places the emphasis on the act of painting rather than the final work as an artistic object.

- Jackson Pollock challenged traditional conventions of painting by using synthetic, resin-based paints, laying his canvas on the floor, and using hardened brushes, sticks, and even basting syringes to apply paint.

Key Terms

- abstract: Art that does not depict objects in the natural world, but instead uses color and form in a non-representational way.

- aesthetic: Concerned with beauty, artistic impact, or appearance.

Action Painting

Action painting is a style of painting in which paint is spontaneously dripped, splashed, or smeared onto the canvas, rather than being carefully applied with a brush. The resulting work often emphasizes the physical act of painting itself as an essential aspect of the finished work.

Action painting is inextricably linked to abstract expressionism, a school of painting popular in post-World War II America that was characterized by the view that art is non-representational and chiefly improvisational. The major artists associated with this movement are Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Robert Motherwell, Franz Kline, and Mark Rothko, among others.

The term action painting was coined by the American art critic Harold Rosenberg in 1952 in his essay The American Action Painters, signaling a major shift in the aesthetic perspective of the New York School painters and critics. According to Rosenberg, the canvas was not an object, but rather “an arena in which to act.”

Rosenberg’s critique shifted the emphasis from the object to the struggle of painting itself, with the finished work being only the physical manifestation, a kind of residue, of the actual work of art, which was in the process of the painting’s creation. This physical emphasis echoed the hyper-masculine atmosphere of the Abstract Expressionists who seemed to see themselves as heroes, American cowboys up against the challenge and danger of the blank canvas. This did not prove good for many of the artists as the stress exhibited itself in alcoholism, depression, suicide and other personal problems.

Action painting refers to the spontaneous activity that was the action of the painter—through arm and wrist movement, painterly gestures— and led to paint that was thrown, splashed, stained, splattered, poured, and dripped. The painter would sometimes let the paint drip onto the canvas while rhythmically dancing or even while standing on top of the unstretched canvas laying on the floor—both techniques invented by one of the most important abstract expressionists: Jackson Pollock.

Jackson Pollock

“My painting does not come from the easel. I prefer to tack the unstretched canvas to the hard wall or the floor. I need the resistance of a hard surface. On the floor I am more at ease. I feel nearer, more part of the painting, since this way I can walk around it, work from the four sides, and literally be in the painting.” Jackson Pollock in Jackson Pollock 51, 1951 (excerpt) Hans Namuth and Paul Falkenberg (directors) Morton Feldman (composer).

Born in Cody, Wyoming in 1912, Jackson Pollock moved to New York City in 1930, where he studied under Thomas Hart Benton at the Art Students League of New York. From a young age Pollock had been an alcoholic and in New York he would undertake therapy from a Jungian analyst in an effort to overcome it. Some of the Jungian archetypes made their way into his earlier abstract paintings like the She-Wolf from 1943. In 1948 he married the American painter Lee Krasner, and they moved to what is now known as the Pollock-Krasner House and Studio in the Springs area of East Hampton, Long Island, NY, with a down payment provided by collector and socialite Peggy Guggenheim.

Materials and Process

After his move to Springs, he began painting with his canvases laid out on the studio floor, turning to synthetic, resin-based paints called alkyd enamels. These were much more fluid than traditional paint and, at that time, were a novel medium. Pollock described his use of household paints, instead of fine art paints, as “a natural growth out of a need.”

He used hardened brushes, sticks, and even basting syringes as paint applicators. By defying the convention of painting on an upright surface, he added a new dimension by being able to view and apply paint to his canvases from all directions—the term all-over painting has been used to describe some of his work, as well as the work of other artists from that time.

In the process of making paintings in this way, he moved away from figurative representation, and challenged the Western tradition of using easel and brush. In addition, he also moved away from the use of only the hand and wrist, since he used his whole body to paint.

Titles with Numbers

Pollock wanted an end to the search for figurative elements in his paintings, so he abandoned titles and started numbering his paintings instead. The numbering relates to the way composers title their works. Furthering the musical metaphor, Pollock’s action paintings have been often described as improvisational works of art, similar to how jazz musicians approach the performance of a piece.

Death

At the peak of his fame, Pollock abruptly abandoned the drip style and by 1951 his works had turned darker in color. This was followed by a return to color, and he reintroduced figurative elements. During this period Pollock moved to a more commercial gallery and there was great demand from collectors for his new paintings.

In response to this pressure, along with personal frustration, his long-term problem with alcoholism worsened. He painted his two last works in 1955. On August 11, 1956, Pollock died in a single-car crash in his Oldsmobile convertible while driving under the influence of alcohol.

After Pollock’s demise at age 44, his widow, Lee Krasner, managed his estate and ensured that Pollock’s reputation remained strong despite changing art-world trends. They are both buried in Green River Cemetery in Springs, Long Island, NY.

Willem de Kooning vied with Jackson Pollock for the title of King of Abstract Expressionism in the 1950s. De Kooning had come to America from the Netherlands with a degree in art. He initially made a living painting billboards and like Pollock sometimes used housepaint in his work. De Kooning shocked the New York art world when he exhibited a series of violently paintings with a recognizable image of a woman as the subject. The Woman series was disturbing to the abstract artists and critics not because of the suggestion of misogyny, but because it reinserted recognizable imagery into a here-to-fore nonrepresentational movement.

9th Street Art Exhibition

The 9th Street Art Exhibition was held on May 21–June 10, 1951. It was a historical, ground-breaking exhibition that gathered a number of notable artists, and it was the stepping-out of the post-war New York avant-garde, collectively known as the New York School.

The show was hung by Leo Castelli, an art dealer who had fled Europe to escape WWII and who became possibly the most influential dealer in New York for the rest of his life; he was liked by most of the artists and thought of as someone who would hang the exhibition without favoritism. The opening of the show was a great success.

There are also commonalities among the New York School and members of the beat-generation poets who were active in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s in New York City, including Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, William S. Burroughs, Diane Wakoski, and several others.

Color-Field Painting

Color-field painting can be recognized by its large fields of solid color spread across or stained into the canvas to create areas of unbroken surface and a flat picture plane.

Learning Objectives

- Differentiate color-field painting from other contemporary abstract art such as Abstract Expressionism.

Key Points

- Color-field painting is a style of abstract painting that emerged in New York City during the 1950s and 1960s. It is closely linked to abstract expressionism, post-painterly abstraction, and lyrical abstraction.

- Distinct from the emotional energy and gestural surface marks and paint handling seen in the work of abstract expressionists like Jackson Pollock, color-field painting came across as cool and austere.

- The movement places less emphasis on gesture, brushstrokes, and action in favor of an overall consistency of form and process, with color itself becoming the subject matter.

- Mark Rothko, Frank Stella, Clyfford Still, Barnett Newman, Adolph Gottlieb, and Morris Louis are among the many artists who used color-field techniques in their work.

- Color-field painters revolutionized the way paint could be effectively applied, through their use of acrylic paint and techniques such as staining and spraying.

Key Terms

- abstract expressionism: An American genre of modern art that used improvised techniques to generate highly abstract forms.

- action painting: A genre of modern art in which the paint is dribbled, splashed, or poured onto the canvas to obtain a spontaneous and totally abstract image.

- lyrical abstraction: A type of abstract painting related to abstract expressionism; in use since the 1940s.

Color-Field Painting

Color-field painting is a style of abstract painting that emerged in New York City during the 1950s and 1960s. Inspired by European modernism and closely related to Abstract Expressionism, many of its notable early proponents were among the pioneering abstract expressionists.

Color-field is characterized primarily by its use of large fields of flat, solid color spread across or stained into the canvas to create areas of unbroken surface and a flat picture plane. The movement places less emphasis on gesture, brushstrokes, and action than Abstract Expressionism, favoring instead an overall consistency of form and process, with color itself becoming the subject matter.

Clement Greenberg

The focus of attention in the contemporary art world began to shift from Paris to New York after World War II and the development of American Abstract Expressionism. During the late 1940s and early 1950s, Clement Greenberg was the first art critic to suggest and identify a dichotomy between differing tendencies within the abstract expressionist canon—especially between action painting and what Greenberg termed post-painterly abstraction (today known as color-field).

Color-Field Formats

By the late 1950s and early 1960s, young artists began to break away stylistically from abstract expressionism, experimenting with new ways of handling paint and color. Moving away from the gesture and angst of action painting towards flat, clear picture planes and a seemingly calmer language, color-field artists used formats of stripes, targets, and simple geometric patterns to concentrate on color as the dominant theme their paintings.

Color-field painting initially referred to a particular type of Abstract Expressionism, exemplified especially in the work of Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still, Barnett Newman, Robert Motherwell, Adolph Gottlieb and several series of paintings by Joan Miró.

Color-field painting sought to rid art of superfluous rhetoric and gesture. Artists like Morris Louis, Jules Olitski, and Kenneth Noland often used greatly reduced formats, simplified or regulated systems, and basic references to nature to draw the focus of the painting to color, and the interactions of color, as the most important element.

This color-field painting is characterized by simple geometric forms and repetitive, regulated systems. It was painted by Kenneth Noland in 1958. The target-like shape will become reified in the work of Jasper Johns at about this time.

The flat, solid picture plane that is typical of color-field paintings is evident in this 1966 piece by Barnett Newman, where the color red takes center stage.

An important distinction between color-field painting and abstract expressionism is the way paint is handled. The most basic defining technique of painting is the application of paint, and the color-field painters revolutionized the way paint could be effectively applied.

Water-soluble, artist-quality acrylic paints first became commercially available in the early 1960s, coinciding with the color-field movement. The most common applications were:

- Soak-Stain painting, where artists mix and dilute their paint in buckets or coffee cans to make it a more fluid liquid, then pour it onto raw, unprimed canvas and draw shapes and areas as they stain. Pioneered by Helen Frankenthaler.

- Spray painting, a technique using a spray gun to create large expanses and fields of color sprayed across the canvas.

- The use of stripes, or “zips” as Barnett Newman characterized them.

Color-field painting initially appeared to be cool and austere due to these methods of handling paint that tended to eschew the individual mark of the artist. However, color-field painting has proven to be both sensual and deeply expressive, albeit in a different way from gestural abstract expressionism.

Mark Rothko

Rothko immigrated to the United States from Russia in 1913. His family settled in Portland, Oregon. Rothko would eschew the family business, go to Yale on a scholarship, and move to New York where he would become part of the New York School. He identified as an Abstract Expressionist, but his mature paintings are basically large floating areas of color. He has written about a kind of spiritual dimension to be found in the paintings, but they share many of the qualities of other color-field work.

His personal life became troubled in his later years and like Gorky – and, arguably, Pollock – he committed suicide. After his death the de Menil family in Houston had a chapel built to house several of his paintings. Given his specific description of his intention and effect as meditative, this was a particularly significant way to honor the artist and his work.

While Abstract Expressionism was the major American art movement of the early Post-War era with influence all over the world, younger generations of artists would find it a useful point against which to push as they moved American painting into new and even more avant-garde areas.