6 Printmaking

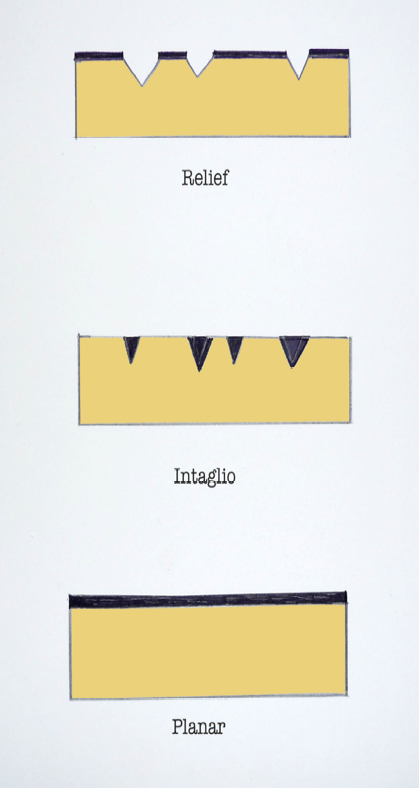

Printmaking is a process of multiples. It uses a transfer process to make multiples from an original image or template. Each image, or individual print, is called an impression, and multiple impressions are printed in an edition, with each print signed and numbered by the artist. All printmaking mediums result in images reversed from the original. Print results depend on how the template (or matrix) is prepared. There are three basic techniques of printmaking: Relief, Intaglio, and Planar (Lithography). You can get an idea of how they differ from the cross-section images below, and view how each technique works from this site – https://www.moma.org/interactives/projects/2001/whatisaprint/print.html – at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Other printmaking processes are silkscreen printing and digital ink jet printing.

Relief Painting

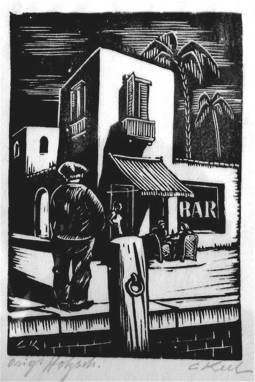

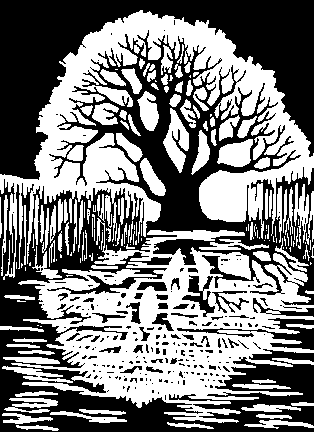

A relief print, such as a woodcut or linoleum cut, is created when the areas of the matrix (plate or block) that are to show the printed image are on the original surface; the parts of the matrix that are to be ink free having been cut away, or otherwise removed. The printed surface is in relief from the cut away sections of the plate. Once the area around the image is cut away, the surface of the plate is rolled up with ink. Paper is laid over the matrix, and both are run through a press, transferring the ink from the surface of the matrix to the paper. The nature of the relief process doesn’t allow for lots of detail, but does result in graphic images with strong contrasts. The bottom of your sneaker makes a relief print on the floor after you walk through mud. A rubber stamp makes a relief print. Carl Eugene Keel’s ‘Bar‘ shows the effects of a woodcut printed in black ink.

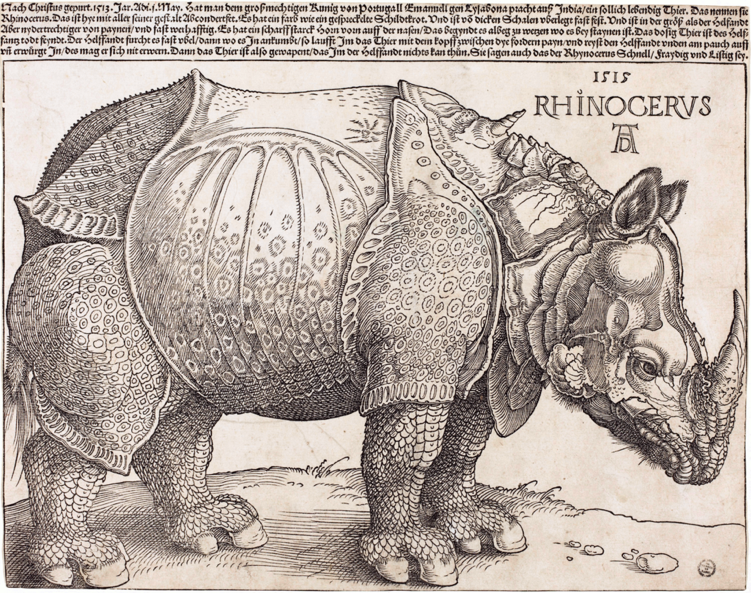

In 1515, Albrecht Dürer made a woodcut showing an animal no one on the European continent – including Dürer himself – had ever seen. His Rhinoceros was based on a written description and brief sketch done by an unknown artists of an Indian rhinoceros that was shipped to Lisbon that year. Sadly, the rhino died in a shipwreck en route to Pope Leo X and another wasn’t brought to Europe until 1577. Dürer’s portrayal isn’t accurate, but it does suggest the artist conflating an “armored” animal with the kind of armor worn by knights including a ‘gorget’ at the neck.1

Block printing developed in China hundreds of years ago and was common throughout East Asia. The Japanese woodblock print below shows dynamic effects of implied motion and the contrasts created using only one color and black. Ukiyo-e, or “floating world,” prints became popular in the 19th century, even influencing European artists during the Industrial Revolution.

Relief printmakers can use a separate block or matrix for each color printed or, in reduction prints a single block is used, cutting away areas of color as the print develops. This method can result in a print with many colors.

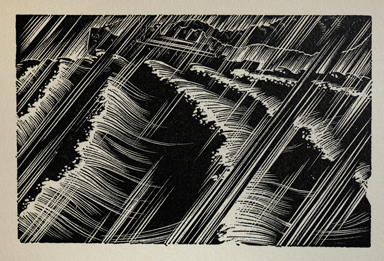

Wood Engraving

The difference between a woodcut and a wood engraving is the part of the tree that is used as matrix. Instead of the soft horizontal wood a wood engraving is made on the harder end cut of the wood and results in shaper, crisper lines. Rockwell Kent’s image of a worker from the days of the labor union in the U.S. fighting back against the agents of capitalism (note the bayonets on the right) is much darker with greater contrasts of light and dark that you might expect to see in an ordinary woodcut.

Linocut

A linoleum cut, or linocut, is created using the same process as a woodcut, but the matrix is the very soft material of linoleum. Long a student favorite, many examples of high-quality linocut art can be found. The lines tend to be broad with stark areas of black and white, although linocuts can also be printed in colors.

Intaglio Printing

Intaglio prints such as etchings, are made by incising channels into a copper or metal plate with a sharp instrument called a burin to create the image, inking the entire plate, then wiping the ink from the surface of the plate, leaving ink only in the incised channels below the surface. Paper is laid over the plate and put through a press under high pressure, forcing the ink to be transferred to the paper.

Engraving is the oldest of intaglio techniques and traces its history back to the intricate designs cut into metal armor by medieval armor-makers. This was the process used most often to create and disseminate images before mechanical methods of the 19th century arrived.

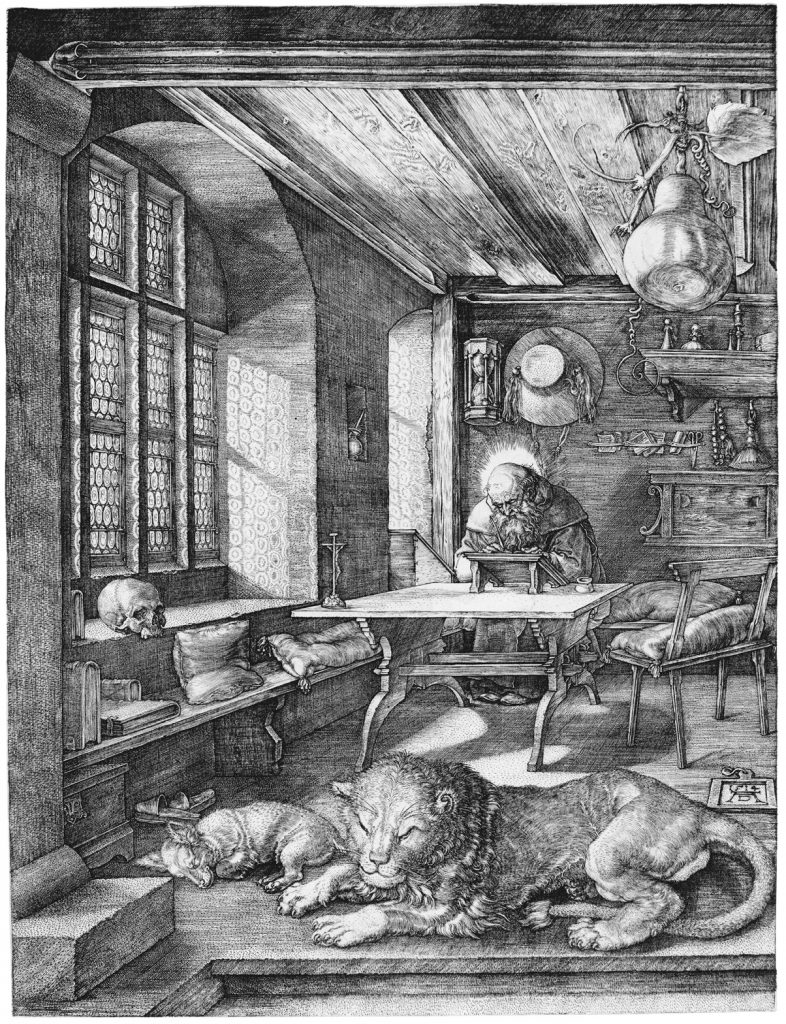

Once again, we see artist Albrecht Dürer turning his skill to another medium to create this image of St. Jerome in his study. Prints were a source of additional income for artists throughout history. You could spend months on one painting and sell it once, but you could create a plate and make a hundred prints to sell.

In dry point, the artist creates an image by scratching the burin directly into a metal plate (usually copper) before inking and printing. Characteristically these prints have strong line quality and exhibit a slightly blurred edge to the line as the result of burrs created in the process of incising the plate, similar to clumps of soil laid to the edge of a furrowed trench. Today artists also use plexi-glass, a hard clear plastic, as plates. A fine example of dry point is seen in Rembrandt’s Clump of Trees with a Vista. The velvety darks are created by the effect of the burred-edged lines.

Etched Printing

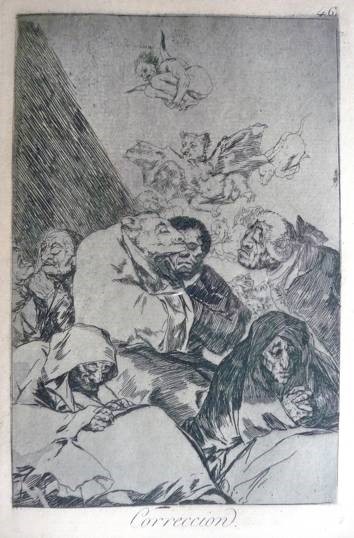

Etching begins by first applying a protective wax-based coating to a thin metal plate. The artist then scratches an image with a burin through the protective coating into the surface of the metal. The plate is then submersed in a strong acid bath, etching the exposed lines. The plate is removed from the acid and the protective coating is removed from the plate. Now the bare plate is inked, wiped and printed. The image is created from the ink in the etched channels. The amount of time a plate is kept in the acid bath determines the quality of tones in the resulting print: the longer it is etched the darker the tones will be. ‘Correccion’ by the Spanish master Francisco Goya shows the clear linear quality etching can produce. The acid bath removes any burrs created by the initial dry point work, leaving details and value contrasts consistent with the amount of lines and the distance between them. Goya presents a fantastic image of people, animals and strange winged creatures. His work often involved biting social commentary. ‘Correccion’ is a contrast between the pious and the absurd.

Mezzotint

Mezzotint is the only process the inventor of which is actually recorded. In 17th century Utrecht, in the Netherlands, an artist named Ludwig von Seiden created a unique printmaking process and no one, he claimed, would be able to figure out how he did it. In fact, the image he sent to William VI, a nobleman of Hesse-Kassel, of his mother in 1642 is thought to be the first mezzotint ever made.

Mezzotint is a tonal process made with a metal tool called a “rocker”. By rocking the half moon shaped tool with tiny teeth or points across the metal plate areas that proceed from dark to light through a soft progression of values can be created.

Goya created editions of prints on a number of subjects. Correccion is #46 from Los Caprichos (The Caprices), 1799. The subject of this set of prints was the foibles and stupidities of the human race. Here we see him using a combination of etching for the fine line work and aquatint, a process that uses a powdered rosin, to create a tonal effect. The acid resistant rosin is usually dusted across the plate and heated to cause it to adhere. The plate can then be dipped in an acid bath for various periods of time and with different sections of plate exposed causing those areas to be more deeply “bitten” and hold more ink. This also results in a tonal product but areas of highlight usually are marked by a hard edge since it has to be painted or stopped out on the plate.

There are many different techniques associated with intaglio, including aquatint, scraping and burnishing.

Planar Printing

Planar prints like monoprints are created on the surface of the matrix without any cutting or incising. In this technique the surface of the matrix (usually a thin metal plate or Plexiglass) is completely covered with ink, then areas are partially removed by wiping, scratching away or otherwise removed to form the image. Paper is laid over the matrix, then run through a press to transfer the image to the paper. Monoprints (also monotypes) are the simplest and painterly of the printing mediums. By definition monotypes and monoprints cannot be reproduced in editions. It is a singular print-making process. Kathryn Trigg’s http://www.kathryntrigg.com/gallery.html monotypes show how close this print medium is related to painting and drawing.

Lithography is another example of planar printmaking, developed in Germany in the late 18th century. “Litho” means “stone” and “graph” means “to draw”. The traditional matrix for lithography is the smooth surface of a limestone block.

While this matrix is still used extensively, thin zinc plates have also been introduced to the medium. They eliminate the bulk and weight of the limestone block but provide the same surface texture and characteristics. The lithographic process is based on the fact that grease repels water. In traditional lithography, an image is created on the surface of the stone or plate using grease pencils or wax crayons or a grease-based liquid medium called tusche. The finished image is covered in a thin layer of gum arabic that includes a weak solution of nitric acid as an etching agent. The resulting chemical reaction divides the surface into two areas: the positive areas containing the image and that will repel water, and the negative areas surrounding the image that will be water receptive. In printing a lithograph, the gum arabic film is removed and the stone or metal surface is kept moist with water so when it’s rolled up with an oil based ink the ink adheres to the positive (image) areas but not to the negative (wet) areas.

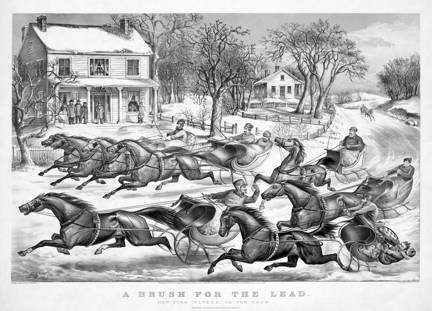

Because of the mediums used to create the imagery, lithographic images show characteristics much like drawings or paintings. In A Brush for the Lead by Currier and Ives (below), a full range of shading and more linear details of description combine to illustrate a winter’s race down the town’s main road.

Serigraphy, also known as screen-printing, is a third type of planar printing medium. Screen-printing is a printing technique that uses a woven mesh to support an ink-blocking stencil. The attached stencil forms open areas of mesh that transfer ink or other printable materials that can be pressed through the mesh as a sharp-edged image onto a substrate such as paper or fabric. A roller or squeegee is moved across the screen stencil, forcing or pumping ink past the threads of the woven mesh in the open areas. The image below shows how a stencil’s positive (image) areas are isolated from the negative (non-image) areas.

In serigraphy, each color needs a separate stencil. You can watch how this process develops in this video

Screen printing is an efficient way to print posters, announcements and other kinds of popular culture images. Andy Warhol began using the silk screen process in the 1960’s. He was thrilled with the mechanical quality of the prints and the sometimes random results he got. He used silk screen images and iconography from popular culture and newspapers to play with the idea of popular versus high art.

Digital Inkjet Prints

This twentieth century technique has made printmaking available to a wide range of art patrons and has allowed artists to do things that would not have been imaginable a few decades ago. What is the difference between an inkjet print made by an artist that sells for a thousand dollars and one from a big box store that sells for less than a hundred? There are several significant differences. First, the machine that makes art prints can handle very large format prints. Second, the artist is on hand to approve, sign, and number every print that comes off the “press”. Finally, artists’ inkjet prints are made with archival quality inks and papers that are intended to last much longer than commercial printing mediums. Another advantage to art inkjet printing is that it can be done on unusual materials. Betsabee Romero, a Mexican artist, prints on car tires (and with car tires, but that’s another process), sunglasses and other objects.

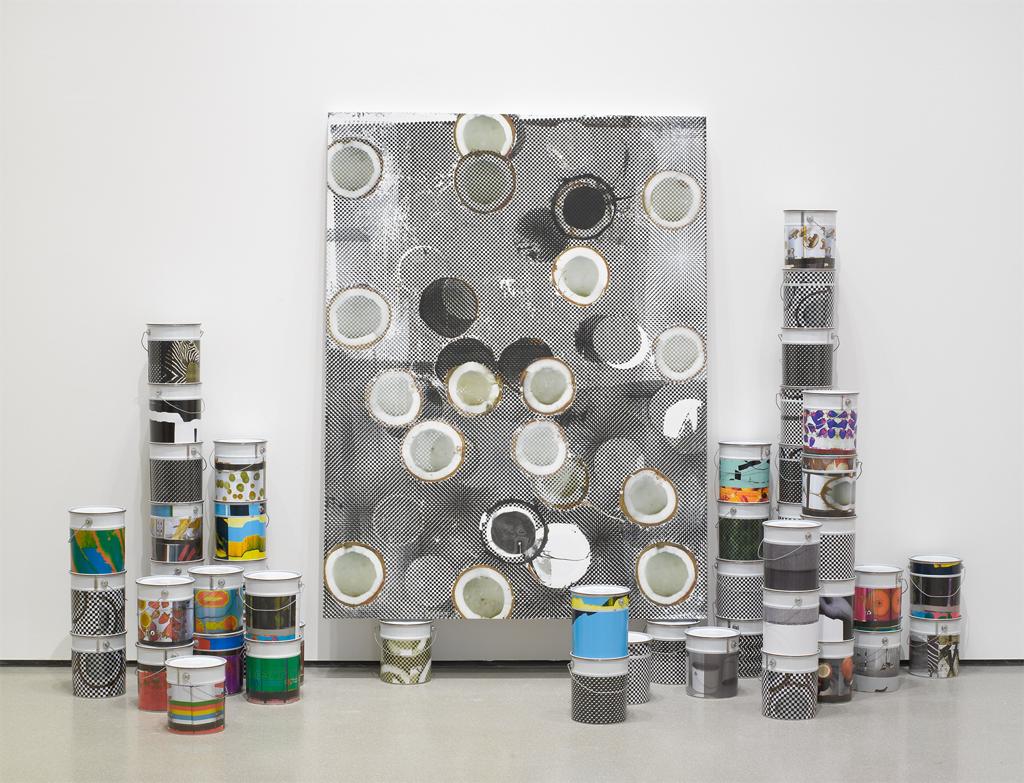

New York artists Wade Guyton and Kelley Walker use the inkjet printer and scanner in their multi-media work. They have printed on objects like paint cans, mattresses, and drywall or furniture.

Important artists are also making prints. One of the best printmaking facilities is Santa Fe Editions. Here artists like Caio Fonseca, Robert Kelly, and Ricardo Mazal have created images that are reproduced in small editions at prices far below that of their paintings. Here the artists work with a master printmaker to create original works, not reproductions, that are then signed and numbered by the artist. The average edition is 30 prints, printed and shipped flat, not rolled. Take a look at some of the work being done at Santa Fe Editions.

http://www.sfeditions.com/MainFrameset-30.htm